‘With a Little Help from My Friends’: Emotional Intelligence, Social Support, and Distress during the COVID-19 Outbreak

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Individual Level Resources

2.2. Social Level Resources: Social Support

2.3. Psychological Distress: Stress, Anxiety, and Depression

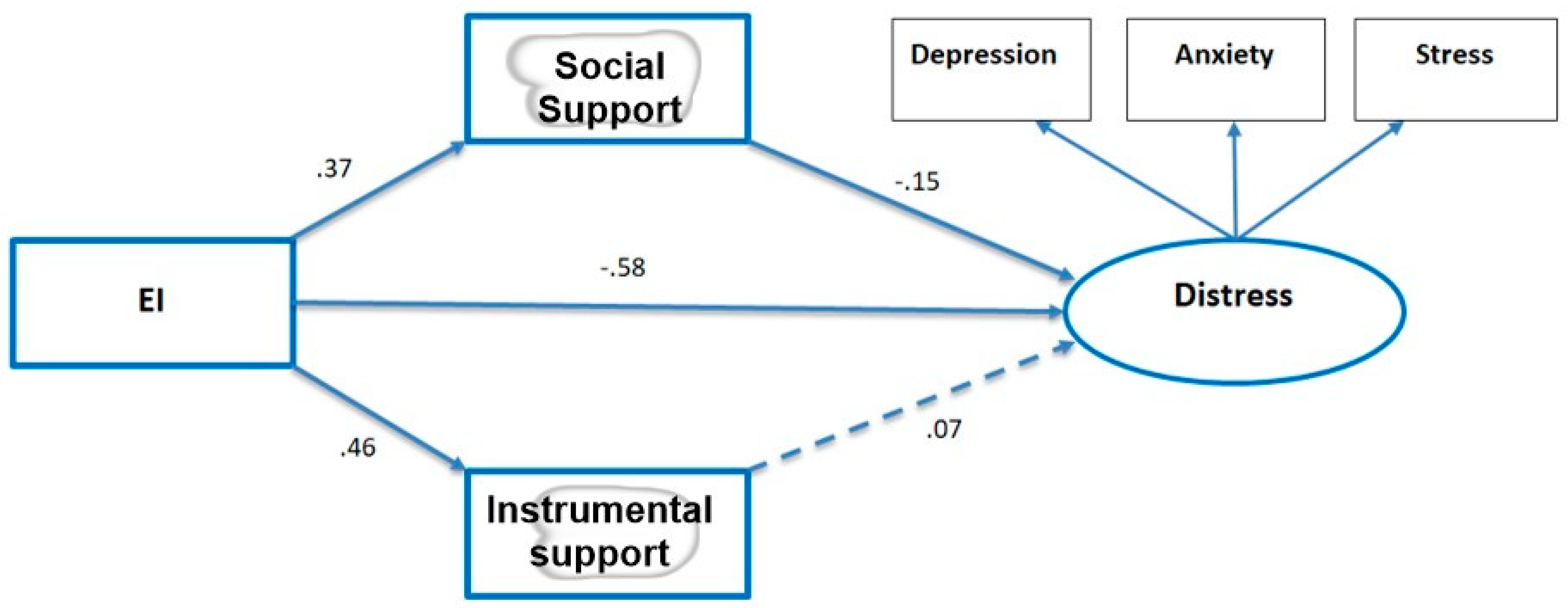

2.4. The Study Model

3. Method

Setting and Sample

4. Measures

4.1. Emotional Intelligence

4.2. Social Support

4.3. Psychological Distress

4.4. Procedure and Ethics

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Model Testing

6. Discussion

The Study’s Contribution

7. Study Limitations

8. Future Work

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak; (No. WHO/2019-nCoV/MentalHealth/2020.1); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenntemich, L.; von Hülsen, L.; Schäfer, I.; Böttche, M.; Lotzin, A. Coping Profiles and Differences in Well-being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Profile Analysis. Stress Health 2022. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibley, C.G.; Greaves, L.M.; Satherley, N.; Wilson, M.S.; Overall, N.C.; Lee, C.H.J.; Milojev, P.; Bulbulia, J.; Osborne, D.; Milfont, T.L.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Nationwide Lockdown on Trust, Attitudes toward Government, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zysberg, L.; Zisberg, A. Days of Worry: Emotional Intelligence and Social Support Mediate Worry in the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 27, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M.; Heesterbeek, H.; Klinkenberg, D.; Hollingsworth, T.D. How Will Country-Based Mitigation Measures Influence the Course of the COVID-19 Epidemic? Lancet 2020, 395, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marroquín, B.; Vine, V.; Morgan, R. Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects of Stay-at-Home Policies, Social Distancing Behavior, and Social Resources. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Nayar, K.R. COVID 19 and Its Mental Health Consequences. J. Ment. Health 2020, 27, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Lu, Z.A.; Que, J.Y.; Huang, X.L.; Liu, L.; Ran, M.S.; Gong, Y.M.; Yuan, K.; Yan, W.; Sun, Y.K.; et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors Associated with Mental Health Symptoms among the General Population in China during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. 2020, 3, e2014053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, C.; Hegde, S.; Smith, A.; Wang, X.; Sasangohar, F. Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in the General Population: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The Psychological Impact of Quarantine and How to Reduce It: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfin, D.R.; Silver, R.C.; Holman, E.A. The Novel Coronavirus (COVID-2019) Outbreak: Amplification of Public Health Consequences by Media Exposure. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Fan, F.; et al. Mental Health Problems and Correlates among 746 217 College Students during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in China. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, N. Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Quality during COVID-19 Outbreak in China: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of Stress, Anxiety, Depression among the General Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, A.M.; Hoban, M.T.; Lipson, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Eisenberg, D. More than Inconvenienced: The Unique Needs of US College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 48, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathelet, M.; Duhem, S.; Vaiva, G.; Baubet, T.; Habran, E.; Veerapa, E.; Debien, C.; Molenda, S.; Horn, M.; Grandgenèvre, P.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Disorders among University Students in France Confined during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. 2020, 3, e2025591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Yan, S.; Zong, Q.; Anderson-Luxford, D.; Song, X.; Lv, Z.; Lv, C. Mental Health of College Students during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 280, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mridul, B.; Sharma, D.; Kaur, N. Online Classes during COVID-19 Pandemic: Anxiety, Stress & Depression among University Students. Indian J. Forensic. Med. Toxicol. 2021, 15, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, A.K.; Full, K.M.; Cheng, B.; Gravagna, K.; Nederhoff, D.; Basta, N.E. Stress, Anxiety, and Sleep among College and University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, A.; Chen, Y. College Students’ Stress and Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Academic Workload, Separation from School, and Fears of Contagion. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, D.; Camart, N.; Romo, L. Predictors of Stress in College Students. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çalık, M. Determining the Anxiety and Anxiety Levels of University Students in the COVID 19 Outbreak. Int. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Invent. 2020, 7, 4887–4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, M.A.; Lerma, E.; Vela, J.C.; Watson, J.C. Predictors of Academic Stress among College Students. J. Coll. Couns. 2019, 22, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Javed, S. Perceived Stress among University Students in Oman during COVID-19-Induced e-Learning. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2021, 28, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, K.; Sharma, M.; Batra, R.; Singh, T.P.; Schvaneveldt, N. Assessing the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 among College Students: Evidence of 15 Countries. Healthcare 2021, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, A.; Erbiçer, E.S.; Şen, S.; Çetinkaya, A. Gender and COVID-19 Related Fear and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 310, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapeau, A.; Marchand, A.; Beaulieu-Prévost, D. Epidemiology of Psychological Distress. In Mental Illnesses: Understanding, Prediction and Control; L’Abate, L., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necho, M.; Tsehay, M.; Birkie, M.; Biset, G.; Tadesse, E. Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Psychological Distress among the General Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridner, S.H. Psychological Distress: Concept Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 45, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagy, S.; Braun-Lewensohn, O. Adolescents under Rocket Fire: When are coping resources significant in reducing emotional distress? Glob. Health Promot. 2009, 16, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Stanton, A.L. Coping Resources, Coping Processes, and Mental Health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, B.A. Review of the Literature on Community Resilience and Disaster Recovery. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, S.; Eshel, Y.; Zysberg, L.; Hantman, S.; Enosh, G. Sense of Coherence and Socio-Demographic Characteristics Predicting Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Recovery in the Aftermath of the Second Lebanon War. Anxiety Stress Copin. 2010, 23, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. Trait Emotional Intelligence: Psychometric Investigation with Reference to Established Trait Taxonomies. Eur. J. Pers. 2001, 15, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V.; Pita, R.; Kokkinaki, F. The Location of Trait Emotional Intelligence in Personality Factor Space. Br. J. Psychol. 2007, 98, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrides, K.V.; Mikolajczak, M.; Mavroveli, S.; Sanchez-Ruiz, M.J.; Furnham, A.; Pérez-González, J.C. Developments in Trait Emotional Intelligence Research. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrionandia, A.; Mikolajczak, M. A Meta-Analysis of the Possible Behavioural and Biological Variables Linking Trait Emotional Intelligence to Health. Health Psychol. Rev. 2020, 14, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, K.G. Principles of Social Psychology; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A.; McGrath, J.E. Social Support, Occupational Stress and Anxiety. Anxiety Stress Copin. 1992, 5, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.M.; Park, J.W.; Kang, H.S. Relationships of Acculturative Stress, Depression, and Social Support to Health-Related Quality of Life in Vietnamese Immigrant Women in South Korea. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2014, 25, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakey, B.; Orehek, E. Relational Regulation Theory: A New Approach to Explain the Link between Perceived Social Support and Mental Health. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 118, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeszutek, M.; Schier, K. Temperament Traits, Social Support, and Burnout Symptoms in a Sample of Therapists. Psychotherapy 2014, 51, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlberg, L. Loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1161–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, I. COVID-19 Compassion in Self-Isolating Old Age: Looking Forward from Family to Regional and global Concerns. Socio-Ecol. Pract. Res. 2020, 2, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, S. Compassion in a Time of COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1897–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Kala, M.P.; Jafar, T.H. Factors Associated with Psychological Distress during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic on the Predominantly General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, F.; Bi, F.; Jiao, R.; Luo, D.; Song, K. Gender Differences of Depression and Anxiety among Social Media Users during the COVID-19 Outbreak in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundia, L. The Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Stress in Brunei Preservice Student Teachers. Internet J. Ment. Health 2009, 6, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. History of the Stress Concept. In Handbook of Stress, 2nd ed.; Goldberger, L., Breznitz, S., Eds.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, B.H. (Ed.) Coping with Chronic Stress; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, M.; Loi, N.M. The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion in Student Psychological Health. Aust. Psychol. 2016, 51, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Williams, M.K.; Hernandez, P.R.; Agocha, V.B.; Lee, S.Y.; Carney, L.M.; Loomis, D. Development of Emotion Regulation across the First Two Years of College. J. Adolesc. 2020, 84, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zysberg, L. Nontraditional Vulnerable Populations: The Case of International Students. In Caring for the Vulnerable: Perspectives in Nursing Theory, Practice, and Research; DeChesney, M., Ed.; Jones and Barlett: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon, A.; McGrath, S.; Magya, H.; Stapleton, P.; Lo, B. Psychosocial Moderators of Perceived Stress, Anxiety and Depression in University Students: An International Study. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 2, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, C.K.; Ngo, C.; Zulkifli, R.; Vellasamy, R.; Suresh, K. Depression, anxiety and stress among undergraduate students: A cross sectional study. Open J. Epidemiol. 2015, 5, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hasking, P.; et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and Distribution of Mental Disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitt, E.E. The Psychology of Anxiety, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Seligman, M.E. Beyond Money: Toward an Economy of Well-Being. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2004, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, D.J.; Villines, D.; Kim, Y.O.; Epstein, J.B.; Wilkie, D.J. Anxiety, Depression, and Pain: Differences by Primary Cancer. Support Care Cancer 2010, 18, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schachter, S.; Singer, J. Cognitive, Social, and Physiological Determinants of Emotional State. Psychol. Rev. 1962, 69, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnoff, I.; Zimbardo, P.G. Anxiety, Fear, and Social Isolation. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1961, 62, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.A.; Neighbors, H.W.; Griffith, D.M. The Experience of Symptoms of Depression in Men vs Women: Analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A Systematic Review: The Influence of Social Media on Depression, Anxiety and Psychological Distress in Adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion-Regulation Strategies across Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Wisco, B.E.; Lyubomirsky, S. Rethinking Rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 3, 400–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J.; Yang, C.C.; Chiang, H.H. Model of Coping Strategies, Resilience, Psychological Well-Being, and Perceived Health among Military Personnel. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 38, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegling, A.B.; Vesely, A.K.; Petrides, K.V.; Saklofske, D.H. Incremental Validity of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire–Short Form (TEIQue–SF). J. Pers. Assess. 2015, 97, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, U.; Schwarzer, R. Soziale Unterstützung bei der Krankheitsbewältigung: Die Berliner Social Support Skalen (BSSS) [Social Support in Coping with Illness: The Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS)]. Diagnostica 2003, 49, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMillo, J.; Hall, N.C.; Ezer, H.; Schwarzer, R.; Körner, A. The Berlin Social Support Scales: Validation of the Received Support Scale in a Canadian Sample of Patients Affected by Melanoma. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elo, A.; Leppänen, A.; Jahkola, A. Validity of a Single-Item Measure of Stress Symptoms. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2003, 29, 444–451. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40967322 (accessed on 10 October 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derogatis, L.R. Brief Symptom Inventory; Clinical Psychometric Research: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, E.N.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. Social support and emotional intelligence as predictors of subjective well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 44, 1551–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, M.; Matthews, G. Ability emotional intelligence and mental health: Social support as a mediator. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 99, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawford, H.L.; Astrologo, L.; Ramey, H.L.; Linden-Andersen, S. Identity, Intimacy, and Generativity in Adolescence and Young Adulthood: A Test of the Psychosocial Model. Identity 2020, 20, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I.G.; Sarson, B.R.; Pierce, G.R. Anxiety, Cognitive Interference, and Performance. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 1990, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben, D.B.; Siu, A.L.; Kimpau, S. The Predictive Validity of Self-Report and Performance-Based Measures of Function and Health. J. Gerontol. 1992, 47, M106–M110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornas-Biela, D.; Martynowska, K.; Biela-Wołońciej, A. Chronić się przed wirusem czy ukryć przed światem? Noszenie Masek Ochronnych Jako Doświadczenie Psychicznie w Dobie Pandemii COVID-19 [Protect yourself from the virus or hide from the world? Wearing Protective Masks as a Psychological Experience in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic]. In Psychospołeczny Obraz Pierwszej Fali Pandemii COVID-19 w Polsce [a Psychosocial Picture of the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland]; Paluchowski, W.J., Bakiera, L., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM: Poznań, Poland, 2021; pp. 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boullion, G.Q.; Pavlacic, J.M.; Schulenberg, S.E.; Buchanan, E.M.; Steger, M.F. Meaning, Social Support, and Resilience as Predictors of Posttraumatic Growth: A Study of the Louisiana Flooding of August 2016. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean SD | Reliability | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 95% F 5% M | – | – | |||||||

| 2. Exposure | – | 0.03 | – | |||||||

| 3. EI | 132.63 17.46 | 0.79 | 0.09 | 0.06 | – | |||||

| 4. Psych sup | 13.70 2.34 | 0.84 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.36 ** | – | ||||

| 5. Inst sup | 14.00 2.48 | 0.91 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.45 ** | 0.81 ** | – | |||

| 6. Stress | 3.42 0.98 | – | −0.09 | −0.11 | −0.31 ** | −0.08 | −0.23 ** | – | ||

| 7. Anxiety | 9.49 6.12 | 0.91 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.39 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.24 ** | 0.42 ** | – | |

| 8. Depression | 8.27 5.72 | 0.89 | 0.04 | −0.09 | −0.55 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.27 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.63 ** | – |

| Coefficient | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 21.92 | 12.63 | 1.73 | 0.08 |

| EI | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.96 | 0.33 |

| Emotional support | −0.06 | 0.91 | −0.06 | 0.94 |

| Moderation model | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.09 | 0.92 |

| R square = 0.28, F = 20.78 (df = 3), p < 0.00 | ||||

| Coefficient | SE | t | p | |

| Constant | 19.33 | 10.17 | 1.90 | 0.05 |

| EI | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.99 | 0.32 |

| Emotional support | 0.14 | .072 | 0.19 | 0.84 |

| Moderation model | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.31 | 0.75 |

| R square = 0.28, F = 20.33 (df = 3), p < 0.00 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kornas-Biela, D.; Martynowska, K.; Zysberg, L. ‘With a Little Help from My Friends’: Emotional Intelligence, Social Support, and Distress during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032515

Kornas-Biela D, Martynowska K, Zysberg L. ‘With a Little Help from My Friends’: Emotional Intelligence, Social Support, and Distress during the COVID-19 Outbreak. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032515

Chicago/Turabian StyleKornas-Biela, Dorota, Klaudia Martynowska, and Leehu Zysberg. 2023. "‘With a Little Help from My Friends’: Emotional Intelligence, Social Support, and Distress during the COVID-19 Outbreak" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032515

APA StyleKornas-Biela, D., Martynowska, K., & Zysberg, L. (2023). ‘With a Little Help from My Friends’: Emotional Intelligence, Social Support, and Distress during the COVID-19 Outbreak. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032515