Association between Prehospital Visits and Poor Health Outcomes in Korean Acute Stroke Patients: A National Health Insurance Claims Data Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

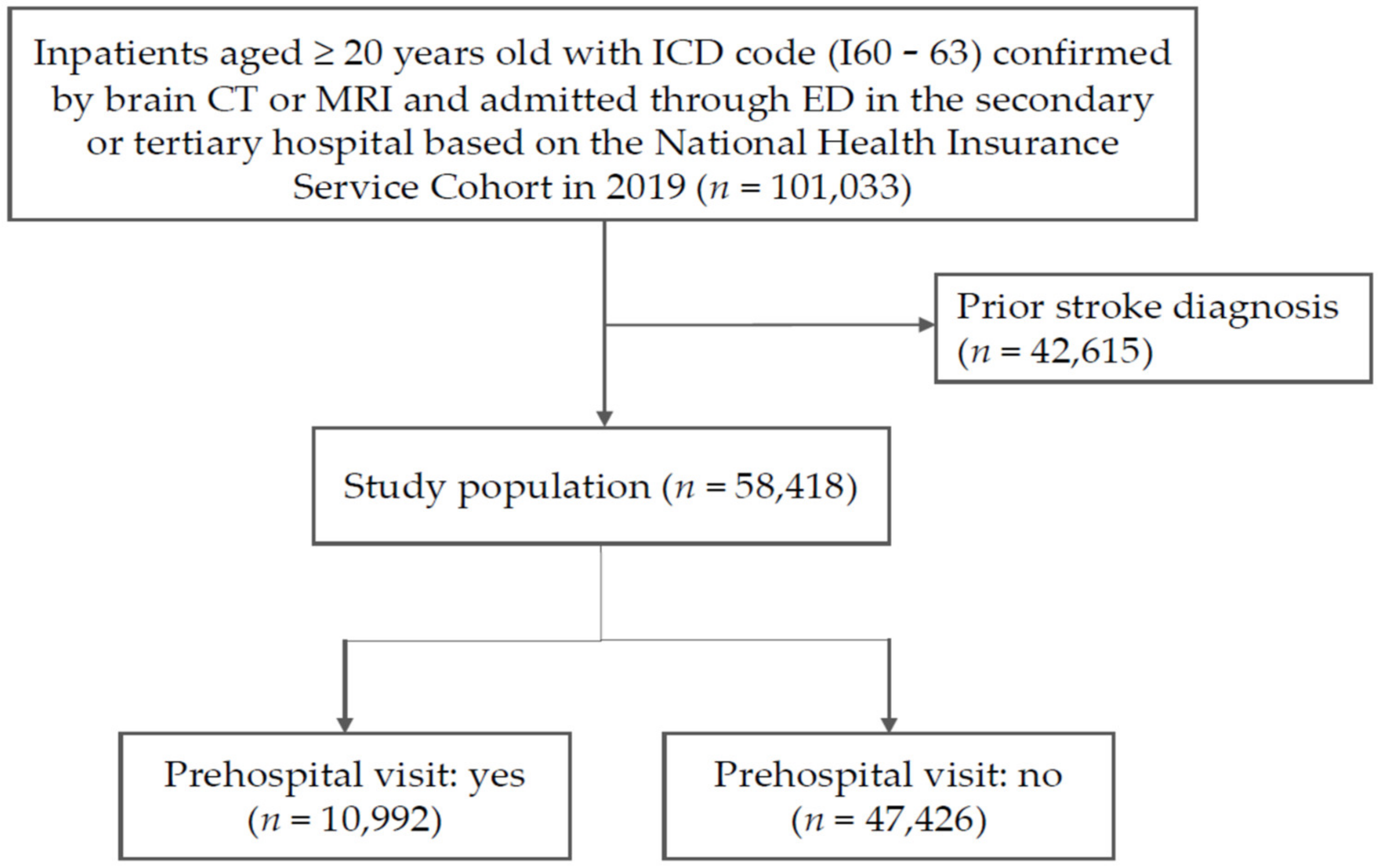

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Health Outcomes According to Prehospital Visits

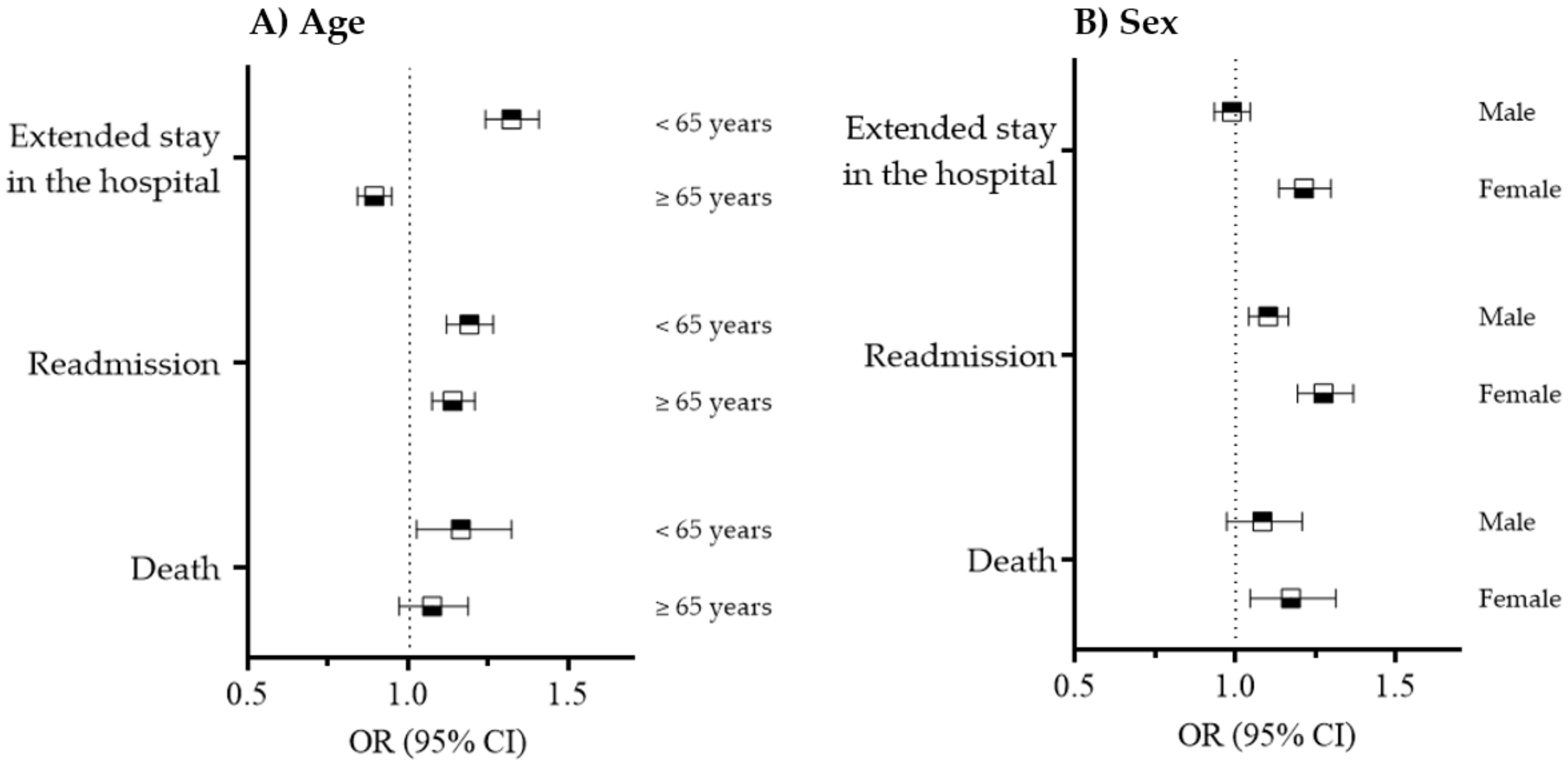

3.3. The Effects of Patient Characteristics on Health Outcomes of Prehospital Visits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhelev, Z.; Walker, G.; Henschke, N.; Fridhandler, J.; Yip, S. Prehospital stroke scales as screening tools for early identification of stroke and transient ischemic attack. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 4, Cd011427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The Top 10 Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Keskin, O.; Kalemoğlu, M.; Ulusoy, R.E. A clinic investigation into prehospital and emergency department delays in acute stroke care. Med. Princ. Pract. Int. J. Kuwait Univ. Health Sci. Cent. 2005, 14, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharobeam, A.; Jones, B.; Walton-Sonda, D.; Lueck, C.J. Factors delaying intravenous thrombolytic therapy in acute ischaemic stroke: A systematic review of the literature. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 2723–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestrelli, G.; Parnetti, L.; Tambasco, N.; Corea, F.; Capocchi, G. Characteristics of delayed admission to stroke unit. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2006, 28, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, E.B.; Rosamond, W.D.; Morris, D.L.; Evenson, K.R.; Hinn, A.R. Determinants of use of emergency medical services in a population with stroke symptoms: The Second Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH II) Study. Stroke 2000, 31, 2591–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, T.; Fujimoto, S.; Inoue, T.; Suzuki, S. Prehospital delay and stroke-related symptoms. Intern. Med. 2015, 54, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; You, S.; Cao, X.; Wang, X.; Gong, W.; Qin, Y.; Huang, X.; Cao, Y.; Shi, R. Factors Associated with Pre-Hospital Delay and Intravenous Thrombolysis in China. J. Stroke Cereb. Dis. 2020, 29, 104897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestroni, A.; Mandelli, C.; Manganaro, D.; Zecca, B.; Rossi, P.; Monzani, V.; Torgano, G. Factors influencing delay in presentation for acute stroke in an emergency department in Milan, Italy. Emerg. Med. J. EMJ 2008, 25, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, W.J.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Ackerson, T.; Adeoye, O.M.; Bambakidis, N.C.; Becker, K.; Biller, J.; Brown, M.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Hoh, B.; et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019, 50, e344–e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, A.B.; Johnsen, S.P.; Blauenfeldt, R.A.; Gude, M.F.; Dalby, R.B.; Christensen, B.; Andersen, G.; Christensen, M.B. Help-seeking behaviour and subsequent patient and system delays in stroke. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2021, 144, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffner, D.; Soriano, C.; Pérez, T.; Vilar, C.; Rodríguez, D. Delay in seeking treatment by patients with stroke: Who decides, where they go, and how long it takes. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2012, 114, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Kim, S.J.; Bae, J.; Lee, E.J.; Kwon, O.D.; Jeong, H.Y.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, H.B. Impact of onset-to-door time on outcomes and factors associated with late hospital arrival in patients with acute ischemic stroke. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, R.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Matsushita, T.; Hata, J.; Kiyuna, F.; Fukuda, K.; Wakisaka, Y.; Kuroda, J.; Ago, T.; Kitazono, T.; et al. Association Between Onset-to-Door Time and Clinical Outcomes After Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2017, 48, 3049–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheol Seong, S.; Kim, Y.Y.; Khang, Y.H.; Heon Park, J.; Kang, H.J.; Lee, H.; Do, C.H.; Song, J.S.; Hyon Bang, J.; Ha, S.; et al. Data Resource Profile: The National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 799–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, R.; Saver, J.L.; Schwamm, L.H.; Fonarow, G.C.; Liang, L.; Matsouaka, R.A.; Xian, Y.; Holmes, D.N.; Peterson, E.D.; Yavagal, D.; et al. Association Between Time to Treatment With Endovascular Reperfusion Therapy and Outcomes in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated in Clinical Practice. Jama 2019, 322, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McTaggart, R.A.; Moldovan, K.; Oliver, L.A.; Dibiasio, E.L.; Baird, G.L.; Hemendinger, M.L.; Haas, R.A.; Goyal, M.; Wang, T.Y.; Jayaraman, M.V. Door-in-Door-Out Time at Primary Stroke Centers May Predict Outcome for Emergent Large Vessel Occlusion Patients. Stroke 2018, 49, 2969–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, Y.D.; Yoon, S.S.; Chang, H. Association of hospital arrival time with modified Rankin scale at discharge in patients with acute cerebral infarction. Eur. Neurol. 2010, 64, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-Jiménez, C.; Ruiz-Sandoval, J.L.; Chiquete, E.; Vega-Arroyo, M.; Arauz, A.; Murillo-Bonilla, L.M.; Ochoa-Guzmán, A.; Carrillo-Loza, K.; Ramos-Moreno, A.; Barinagarrementeria, F.; et al. Hospital arrival time and functional outcome after acute ischaemic stroke: Results from the PREMIER study. Neurologia 2014, 29, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denti, L.; Artoni, A.; Scoditti, U.; Gatti, E.; Bussolati, C.; Ceda, G.P. Pre-hospital Delay as Determinant of Ischemic Stroke Outcome in an Italian Cohort of Patients Not Receiving Thrombolysis. J. Stroke Cereb. Dis. 2016, 25, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Foraker, R.E.; Morris, D.L.; Rosamond, W.D. A comprehensive review of prehospital and in-hospital delay times in acute stroke care. Int. J. Stroke 2009, 4, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zhu, S.; Wei, J.W.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y.; Wong, L.K.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, E.; Yang, Q.; et al. Factors associated with prehospital delays in the presentation of acute stroke in urban China. Stroke 2012, 43, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koton, S.; Telman, G.; Kimiagar, I.; Tanne, D. Gender differences in characteristics, management and outcome at discharge and three months after stroke in a national acute stroke registry. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 4081–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, S.; Hjalmarsson, C.; Andersson, B. Sex differences in risk factors, treatment, and prognosis in acute stroke. Women’s Health 2020, 16, 1745506520952039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irie, F.; Kamouchi, M.; Hata, J.; Matsuo, R.; Wakisaka, Y.; Kuroda, J.; Ago, T.; Kitazono, T. Sex differences in short-term outcomes after acute ischemic stroke: The fukuoka stroke registry. Stroke 2015, 46, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Prehospital Visit | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| N (%) | 58,418 (100) | 10,992 (18.8) | 47,426 (81.2) | <0.001 |

| Stroke type | ||||

| Ischemic stroke | 41,341 (70.8) | 6823 (16.5) | 34,518 (83.5) | <0.001 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 17,077 (29.2) | 4169 (24.4) | 12,908 (76.6) | <0.001 |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 65.9 ± 14.6 | 65.0 ± 14.4 | 66.1 ± 14.6 | <0.001 |

| <65 | 26,786 (45.9) | 5320 (19.9) | 21,466 (80.1) | <0.001 |

| ≥65 | 31,632 (54.1) | 5672 (17.9) | 25,960 (82.1) | |

| Sex | 0.079 | |||

| Male | 32,938 (56.4) | 6280 (19.1) | 26,658 (80.9) | |

| Female | 25,480 (43.6) | 4712 (18.5) | 20,768 (81.5) | |

| Income status | <0.001 | |||

| Medical aid | 3884 (6.7) | 630 (16.2) | 3254 (83.8) | |

| Q1 | 10,659 (18.3) | 2107 (19.8) | 8552 (80.2) | |

| Q2 | 6972 (11.9) | 1296 (18.6) | 5676 (81.4) | |

| Q3 | 8970 (15.4) | 1808 (20.2) | 7162 (79.8) | |

| Q4 | 1539 (19.8) | 2194 (19.0) | 9345 (81.0) | |

| Q5 | 16,394 (28.1) | 2957 (18.0) | 13,437 (82.0) | |

| Urbanization | <0.001 | |||

| High | 37,363 (64.0) | 5639 (15.1) | 31,724 (84.9) | |

| Low | 21,055 (36.0) | 5353 (25.4) | 15,702 (74.6) | |

| Hypertension | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 28,951 (49.6) | 5764 (19.9) | 23,187 (80.1) | |

| No | 29,497 (50.4) | 5228 (17.7) | 24,239 (82.2) | |

| Ischemic heart disease | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 5797 (9.9) | 951 (16.4) | 4846 (83.6) | |

| No | 52,621 (90.1) | 10,041 (19.1) | 42,580 (80.9) | |

| Congestive heart failure | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 4843 (8.3) | 808 (16.7) | 4035 (83.3) | |

| No | 53,575(91.7) | 10,184 (19.0) | 43,391 (81.0) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 4040 (6.9) | 660 (16.3) | 3380 (83.7) | |

| No | 54,378 (93.1) | 10,332 (19.0) | 44,046 (81.0) | |

| Arrhythmia | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1361 (2.3) | 209 (15.4) | 1152 (84.6) | |

| No | 57,057 (97.7) | 10,783 (18.9) | 46,274 (81.1) | |

| Extended Stay in the Hospital | Readmission | Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) | 60.7 | 52.3 | 7.48 |

| Prehospital-visit group (%) | 62.5 | 55.3 | 7.94 |

| No-prehospital-visit group (%) | 60.2 | 51.7 | 7.38 |

| Odds ratio (95% Confidence intervals) | 1.06 * (1.02, 1.10) | 1.19 * (1.14, 1.25) | 1.23 * (1.13, 1.33) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.; Moon, J.; Lee, J.; Jung, S.; Hwang, R.; Kim, M.Y. Association between Prehospital Visits and Poor Health Outcomes in Korean Acute Stroke Patients: A National Health Insurance Claims Data Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032488

Shin J, Kim H, Kim Y, Moon J, Lee J, Jung S, Hwang R, Kim MY. Association between Prehospital Visits and Poor Health Outcomes in Korean Acute Stroke Patients: A National Health Insurance Claims Data Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032488

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Jinyoung, Hyeongsu Kim, Youngtaek Kim, Jusun Moon, Jeehye Lee, Sungwon Jung, Rahil Hwang, and Mi Young Kim. 2023. "Association between Prehospital Visits and Poor Health Outcomes in Korean Acute Stroke Patients: A National Health Insurance Claims Data Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032488

APA StyleShin, J., Kim, H., Kim, Y., Moon, J., Lee, J., Jung, S., Hwang, R., & Kim, M. Y. (2023). Association between Prehospital Visits and Poor Health Outcomes in Korean Acute Stroke Patients: A National Health Insurance Claims Data Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032488