Accreditation of Quality in Primary Health Care in Chile: Perception of the Teams from Accredited Family Healthcare Centers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Target Group

2.3. Data Collection

- Perception regarding the culture of evaluation and accreditation of quality in health.

- Perception about general aspects of the implementation of the quality management policy and achievement of quality accreditation in PHC establishments.

- Facilitating and hindering factors of the implementation and achievement of quality accreditation in the health establishment in areas such as: administrative, organizational, others.

- (a)

- Facilitating factors for the operation of the internal network in the areas administrative, organizational, financial and other aspects that the interviewee wants to comment on.

- (b)

- Factors hindering the operation of the internal network in the areas administrative, organizational, financial and other aspects that the interviewee wants to comment on.

- Assessment and meanings represented by the implementation and achievement of accreditation quality in their health facility.

2.4. Sampling Strategy

2.5. Verbatims

2.6. Presentation and Analysis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Processes to Define the Categories and Subcategories for the Analysis

3.2. Open Phase

3.3. Axial Phase

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CESFAM | Family Healthcare Center |

| CESFAMs | Family Healthcare Centers |

| DISAMU | Municipal Health Directorate |

| GES | Explicit Health Guarantees |

| ISQua | International Society for Quality in Health Care |

| PHC | Primary Health Care |

| SEREMI | Regional Ministerial Secretariat |

| TENS | Higher-Level Nursing Technician |

References

- García, R.E. El concepto de calidad y su aplicación en medicina. Rev. Med. Chil. 2001, 129, 825–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, C.; Scherag, A.; Lütkes, P.; Günther, W.; Jöckel, K.H.; Holtmann, G. Is there an association between hospital accreditation and patient satisfaction with hospital care? A survey of 37000 patients treated by 73 hospitals. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2011, 23, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune, T.; O’Connor, E.; Donaldson, B. Guidance on Designing Healthcare External Evaluation Programmes including Accreditation; International Accreditation Programme (IAP), ISQua Accreditation, The International Society for Quality in Health Care: Dublin, Ireland, 2015; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health Care Accreditation and Quality of Care: Exploring the Role of Accreditation and External Evaluation of Health Care Facilities and Organizations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Quality and Accreditation in Health Care Services: A Global Review; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, S. Impact assessment of accreditation in primary and secondary public health-care institutions in Kerala, India. Indian J. Public Health 2021, 65, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, S.Y. Accreditation of primary health care centres in the KSA: Lessons from developed and developing countries. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tehewy, M.; Salem, B.; Habil, I.; El Okda, S. Evaluation of accreditation program in non-governmental organizations’ health units in Egypt: Short-term outcomes. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2009, 21, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, E.B.; Song, W.; Song, W.; Johnston, J.M. Can hospital accreditation enhance patient experience? Longitudinal evidence from a Hong Kong hospital patient experience survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, D.; Lawrence, S.A.; Kellner, A.; Townsend, K.; Wilkinson, A. Health service accreditation stimulating change in clinical care and human resource management processes: A study of 311 Australian hospitals. Health Policy 2019, 123, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donabedian, A. Quality assessment and assurance: Unity of purpose, diversity of means. Inquiry 1988, 25, 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.H.; Wang, T.; Ramalho, N.C.; Zhou, D.; Hu, X.; Zhao, H. Relationship between patient safety culture and safety performance in nursing: The role of safety behaviour. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2021, 27, e12937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgely, M.S.; Ahluwalia, S.C.; Tom, A.; Vaiana, M.E.; Motala, A.; Silverman, M.; Kim, A.; Damberg, C.L.; Shekelle, P.G. What are the determinants of health system performance? Findings from the literature and a technical expert panel. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2020, 46, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALFadhalah, T.; Al Mudaf, B.; Al Salem, G.; Alghanim, H.A.; Abdelsalam, N.; El Najjar, E.; Abdelwahab, H.M.; Elamir, H. The Association Between Patient Safety Culture and Accreditation at Primary Care Centers in Kuwait: A Country-Wide Multi-Method Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2022, 15, 2155–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subsecretaría de Redes Asistenciales; Ministerio de Salud. Orientaciones para la Planificación y Programación en Red 2022; Technical Report; Ministerio de Salud: Santiago, Chile, 2021.

- Ministerio de Salud. Ley 19937: Modifica el D.L. Nº 2.763, de 1979, Con la Finalidad de Establecer una Nueva Concepción de la Autoridad Sanitaria, Distintas Modalidades de Gestión y Fortalecer la Participación Ciudadana. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile/BCN; 2004; p. 64. Available online: http://bcn.cl/2b1q1 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Ministerio de Salud. Reglamento Sistema de Acreditación para Los Prestadores Institucionales de Salud: Decreto Supremo N° 15, de 2007, del Ministerio de Salud; Ministerio de Salud: Santiago, Chile, 2007.

- Superintendencia de Salud; Gobierno de Chile. Registro de Prestadores Acreditados—Servicios. 2022. Available online: http://www.supersalud.gob.cl/servicios/669/w3-article-6193.html (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Coss-Mandiola, J.; Vanegas-López, J.; Rojas, A.; Carrasco, R.; Dubo, P.; Campillay-Campillay, M. Characterization of communes with quality accredited primary healthcare centers in Chile. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEIS Ministerio de Salud. Departamento de Estadísticas e Información de Salud. 2022. Available online: http://www.deis.cl/ (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Katoue, M.G.; Somerville, S.G.; Barake, R.; Scott, M. The perceptions of healthcare professionals about accreditation and its impact on quality of healthcare in Kuwait: A qualitative study. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021, 27, 1310–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davins Miralles, J. El modelo de acreditación del departament de salut de Catalunya: Un modelo para atención primaria. Rehabilitación 2011, 45, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, M.M.; Gonzalez, J.M.G. The model for accreditation in the Andalusian public health system. Cuad. Relac. Laborales 2017, 35, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amezcua, M. Diez recomendaciones para mejorar la transcripción de materiales cualitativos. Index Enferm. 2022, 31, 239–240. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas.ti. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH [ATLAS.ti 23 Mac], version 23; ATLAS.ti: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, M.K.; Pedersen, L.B.; Siersma, V.; Bro, F.; Reventlow, S.; Søndergaard, J.; Kousgaard, M.B.; Waldorff, F.B. Accreditation in general practice in Denmark: Study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olavarría Gambi, M. Implementación de Políticas Públicas: Lecciones para el Diseño. Análisis de los Casos de Modernización de la Gestión Pública y de la Reforma de Salud en Chile. Rev. CLAD Reforma y Democr. 2017, 67, 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Forascepi Crespo, C. Chile: Nuevos desafíos sanitarios e institucionales en un país en transición. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2018, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvial, X.; Rojas, A.; Carrasco, R.; Duran, C.; Fernandez-Campusano, C. Overuse of health care in the emergency services in Chile. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesse-Sorensen, K.; Fuentes-García, A.; Ilabaca, J. Estructura y funciones de la Atención Primaria de Salud según el Primary Care Assessment Tool para prestadores en la comuna de Conchalí—Santiago de Chile. Rev. Med. Chil. 2019, 147, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud; Organización de Cooperación y Desarrollo Económicos; Banco Mundial. Prestación de Servicios de Salud de Calidad: Un Imperativo Global Para la Cobertura Sanitaria Universal; Organización Mundial de la Salud: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; p. 106.

- El-Jardali, F.; Hemadeh, R.; Jaafar, M.; Sagherian, L.; El-Skaff, R.; Mdeihly, R.; Jamal, D.; Ataya, N. The impact of accreditation of primary healthcare centers: Successes, challenges and policy implications as perceived by healthcare providers and directors in Lebanon. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghareeb, A.; Said, H.; El Zoghbi, M. Examining the impact of accreditation on a primary healthcare organization in Qatar. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Razik, M.S.M.; Tawfik, A.; Hemeda, S.A.; El-Rabbat, M.; Abou-Zeina, H.A.; Abdel-latif, G.A. Quality of primary health care services within the framework of the national accreditation program. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2012, 6, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Saura Llamas, J.; Astier Peña, M.P.; Puntes Felipe, B. La formación en seguridad del paciente y una docencia segura en atención primaria. Atención Primaria 2021, 53, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Beirne, M.; Zwicker, K.; Sterling, P.D.; Lait, J.; Lee Robertson, H.; Oelke, N.D. The status of accreditation in primary care. Qual. Prim. Care 2013, 21, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Goyenechea, M. Public health infrastructure investment difficulties in Chile: Concessions and public tenders. Medwave 2016, 16, e6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillay-Campillay, M.; Calle-Carrasco, A.; Dubo, P.; Moraga-Rodríguez, J.; Coss-Mandiola, J.; Vanegas-López, J.; Rojas, A.; Carrasco, R. Accessibility in people with disabilities in primary healthcare centers: A dimension of the quality of care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, H.O.; Durán, C.; Espinosa, E.; Jerez, A.; Palominos, F.; Hinojosa, M.; Carrasco, R. Monitoring of thermal comfort and air quality for sustainable energy management inside hospitals based on online analytical processing and the Internet of Things. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superintendencia de Salud. Guía Práctica para el Proceso de Acreditación de Prestadores Institucionales de Salud; Technical Report; Superintendencia de Salud: Santiago, Chile, 2020.

- Tam, L.; Burns, K.; Barnes, K. Responsibilities and capabilities of health engagement professionals (HEPs): Perspectives from HEPs and health consumers in Australia. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Cummings, G. The relationship between nursing leadership and patient outcomes: A systematic review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2007, 15, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfantou, D.; Laliotis, A.; Patelarou, A.; Sifaki- Pistolla, D.; Matalliotakis, M.; Patelarou, E. Importance of leadership style towards quality of care measures in healthcare settings: A systematic review. Healthcare 2017, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doricci, G.C.; do Carmo Gullaci Guimarães Caccia-Bava, M.; Guanaes-Lorenzi, C. Relational dynamics of primary health care teams and their impact on co-management. Salud Colect. 2020, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousgaard, M.B.; Thorsen, T.; Due, T.D. Experiences of accreditation impact in general practice—A qualitative study among general practitioners and their staff. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N° | Profession | Age | Gender | Time in Office | CESFAM | Commune | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Psychologist | 33 | Male | 4 years | Candelaria del Rosario | Copiapó | Atacama |

| 2 | Kindergarten educator | 39 | Female | 5 años | Juan Martínez | Copiapó | Atacama |

| 3 | Nurse | 38 | Female | 4 years | Paipote | Copiapó | Atacama |

| 4 | Kinesiologist | 35 | Female | 4 years | Dra. Michelle Bachelet Jeria | Chillán Viejo | Ñuble |

| 5 | Midwife | 38 | Female | 7 months | Isabel Riquelme | Chillán | Ñuble |

| 6 | Kinesiologist | 35 | Female | 7 years | Los Volcanes | Chillán | Ñuble |

| 7 | Nurse | 31 | Female | 3 years | Sol de Oriente | Chillán | Ñuble |

| 8 | Kinesiologist | 35 | Female | 5 years | Ultraestación Dr. Raúl San Martín | Chillán | Ñuble |

| 9 | Nurse-Midwife | 65 | Female | 10 years | Dr. Jorge Sabat | Valdivia | Los Ríos |

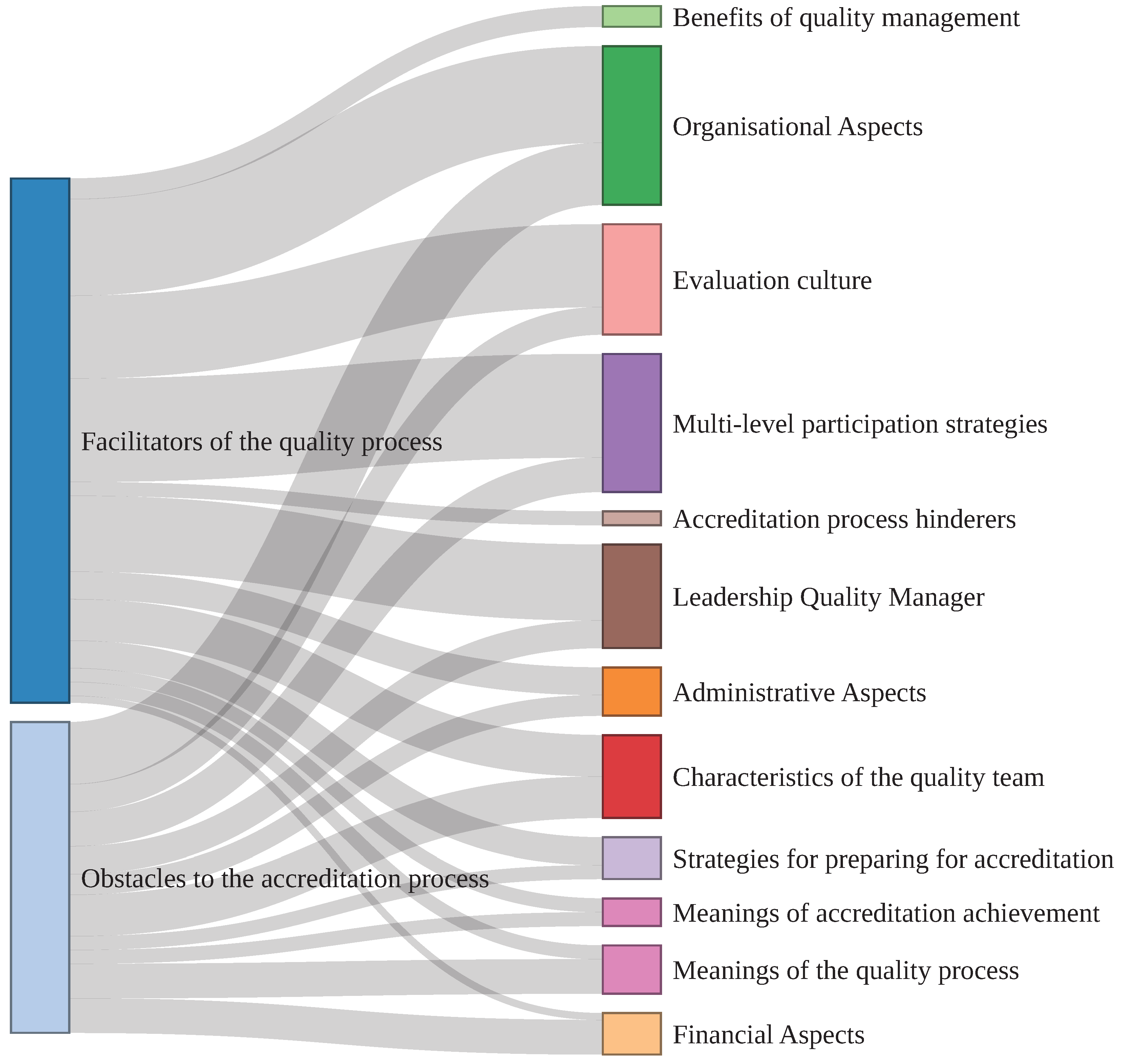

| N° | Core Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quality management policies | Accreditation preparation strategies |

| Meanings of the quality process | ||

| Benefits of quality management | ||

| 2 | Structure of PHC | Administrative aspects |

| Financial aspects | ||

| Organizational aspects | ||

| 3 | Participation and co-construction | Culture of evaluation |

| Multilevel participation strategies | ||

| Characteristics of quality team | ||

| 4 | Leadership and change management | Leadership from people in charge of quality |

| Meanings of accreditation achievement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coss-Mandiola, J.; Vanegas-López, J.; Rojas, A.; Dubó, P.; Campillay-Campillay, M.; Carrasco, R. Accreditation of Quality in Primary Health Care in Chile: Perception of the Teams from Accredited Family Healthcare Centers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032477

Coss-Mandiola J, Vanegas-López J, Rojas A, Dubó P, Campillay-Campillay M, Carrasco R. Accreditation of Quality in Primary Health Care in Chile: Perception of the Teams from Accredited Family Healthcare Centers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032477

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoss-Mandiola, Juan, Jairo Vanegas-López, Alejandra Rojas, Pablo Dubó, Maggie Campillay-Campillay, and Raúl Carrasco. 2023. "Accreditation of Quality in Primary Health Care in Chile: Perception of the Teams from Accredited Family Healthcare Centers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032477

APA StyleCoss-Mandiola, J., Vanegas-López, J., Rojas, A., Dubó, P., Campillay-Campillay, M., & Carrasco, R. (2023). Accreditation of Quality in Primary Health Care in Chile: Perception of the Teams from Accredited Family Healthcare Centers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032477