The Importance of the Outdoor Environment for the Recovery of Psychiatric Patients: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Formulating the initial research question

- Identifying relevant studies

- Select relevant studies

- Charting the data

- Collecting, summarizing, and reporting the results.

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

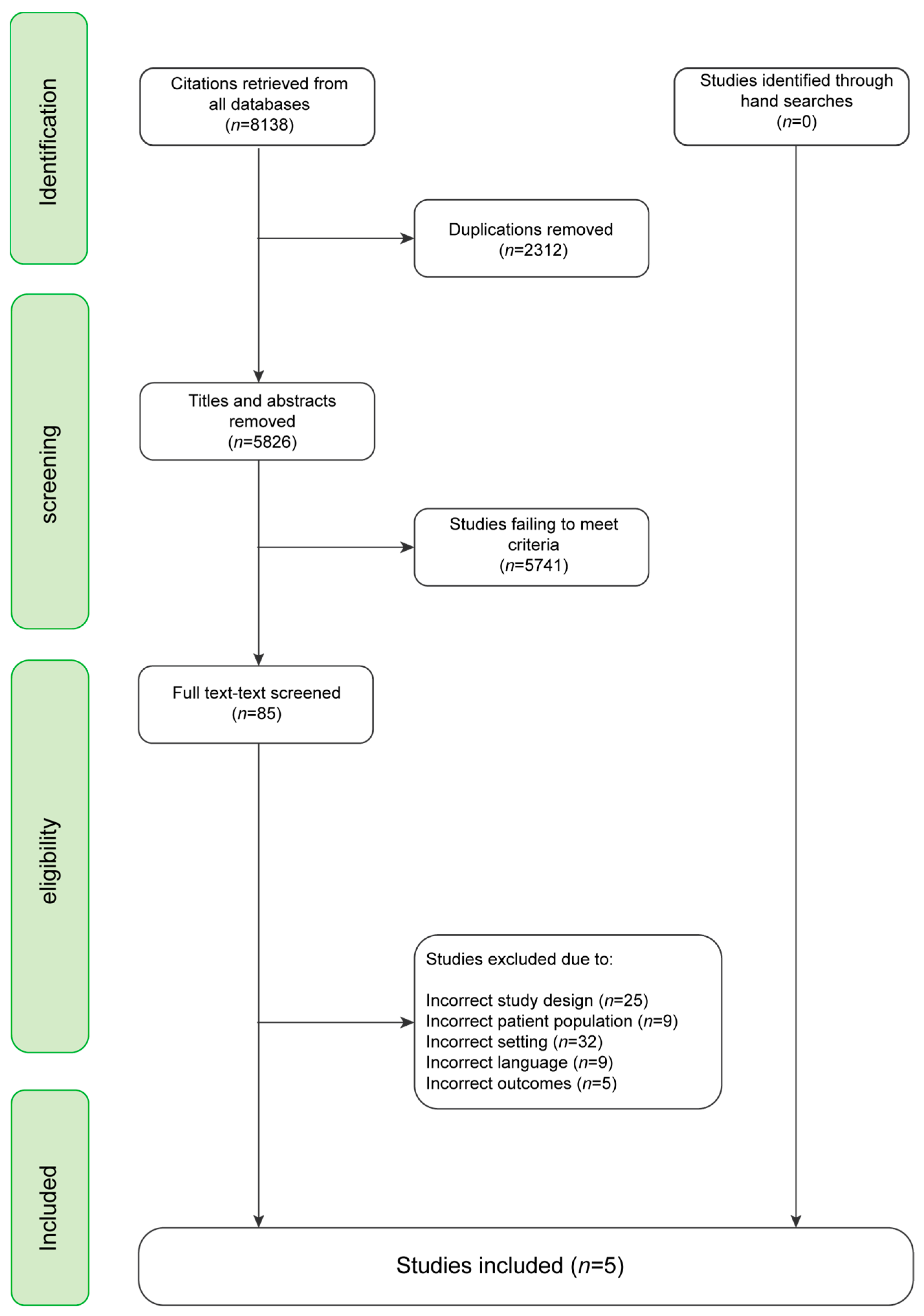

2.3. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.4. Charting the Data

2.5. Collecting, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

3.2. Recovery and Well-Being

3.3. Gardening and Well-Being

3.4. Contact with Nature

3.5. The Safe and Supportive Environment

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1. | Psychiatric* OR Psychiatry*.tw. | |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | Environment OR environments OR gardens OR setting OR settings OR outdoor OR outdoors.tw. | |

| 3. | Recovery.tw. | |

| 4. | psychiatric* OR psychiatry*.ab. | |

| 5. | Environment OR environments OR gardens OR setting OR settings OR outdoor OR outdoors.ab. | |

| 6. | Recovery.ab. | |

| 7. | 1. AND 2. AND 3. AND 4. AND 5. AND 6. | 2486 |

| 1. | Psychiatric* OR Psychiatry*.tw. | |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | Environment OR environments OR gardens OR setting OR settings OR outdoor OR outdoors.tw. | |

| 3. | Recovery.tw. | |

| 4. | psychiatric* OR psychiatry*.ab. | |

| 5. | Environment OR environments OR gardens OR setting OR settings OR outdoor OR outdoors.ab. | |

| 6. | Recovery.ab. | |

| 7. | 1. AND 2. AND 3. AND 4. AND 5. AND 6. | 3115 |

| 1. | Psychiatric* OR Psychiatry*.tw. | |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | Environment OR environments OR gardens OR setting OR settings OR outdoor OR outdoors.tw. | |

| 3. | Recovery.tw. | |

| 4. | psychiatric* OR psychiatry*.ab. | |

| 5. | Environment OR environments OR gardens OR setting OR settings OR outdoor OR outdoors.ab. | |

| 6. | Recovery.ab. | |

| 7. | 1. AND 2. AND 3. AND 4. AND 5. AND 6. | 1805 |

| 1. | Setting OR Settings OR Garden OR Gardens OR Outdoor OR Outdoors OR Environment OR Environments | |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | Recovery | |

| 3. | Psychiatric* OR psychiatry* | |

| 4. | 1. AND 2. AND 3. | 632 |

Appendix B. Google Scholar Search Word Syntax

- (1)

- (outdoor OR garden OR green space) and psychiatric and recovery.

References

- Connellan, K.; Gaardboe, M.; Riggs, D.; Due, C.; Reinschmidt, A.; Mustillo, L. Stressed Spaces: Mental Health and Architecture. HERD: Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2013, 6, 127–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Adams, M.A.; Frank, L.D.; Pratt, M.; Salvo, D.; Schipperijn, J.; Smith, G.; Cain, K.L.; et al. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2016, 387, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudimac, S.; Sale, V.; Kühn, S. How nature nurtures: Amygdala activity decreases as the result of a one-hour walk in nature. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 4446–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høegmark, S.; Andersen, T.E.; Grahn, P.; Mejldal, A.; Roessler, K.K. The Wildman Programme—Rehabilitation and Reconnection with Nature for Men with Mental or Physical Health Problems—A Matched-Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, M.; Aaby, A.; Klausen, S.H.; Roessler, K.K. Are Long-Distance Walks Therapeutic? A Systematic Scoping Review of the Conceptualization of Long-Distance Walking and Its Relation to Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Corazon, S.S.; Sidenius, U.; Kristiansen, J.; Grahn, P. It is not all bad for the grey city-A crossover study on physiological and psychological restoration in a forest and an urban environment. Health Place 2017, 46, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siren, A.; Grønfeldt, S.T.; Andreasen, A.G.; Bukhave, F.S. Sociale Mursten: En Forskningskortlægning af Fysiske Rammers Betydning i Velfærdsindsatser; VIVE: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adevi, A.A.; Mårtensson, F. Stress rehabilitation through garden therapy: The garden as a place in the recovery from stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.S.; Anthony, W.; Lyass, A. The nature and dimensions of social support among individuals with severe mental illnesses. Community Ment. Health J. 2004, 40, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlin, E.; Ahlborg, G., Jr.; Tenenbaum, A.; Grahn, P. Using nature-based rehabilitation to restart a stalled process of rehabilitation in individuals with stress-related mental illness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1928–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, G.; Boardman, J.; Slade, M. Making Recovery a Reality; Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenfeld, A.; Roy-Fisher, C.; Mitchell, C. Collaborative design: Outdoor environments for veterans with PTSD. Facilities 2013, 31, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Essay: Evidence-based health-care architecture. Lancet 2006, 368, S38–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steigen, A.M.; Kogstad, R.; Hummelvoll, J.K. Green Care services in the Nordic countries: An integrative literature review. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 2016, 19, 692–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschner, B.; Slade, M. 2450-The role of clinical decision making in mental health practice. Eur. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Boutillier, C.L.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummelvoll, J.K.; Karlsson, B.; Borg, M. Recovery and person-centredness in mental health services: Roots of the concepts and implications for practice. IPDJ Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2015, 5 (Suppl.), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, W.A. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 2004, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topor, A.; Boe, T.D.; Larsen, I.B. The Lost Social Context of Recovery Psychiatrization of a Social Process. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 832201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2009, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, O.P.; Halswick, D.; Längler, A.; Martin, D.D. Healing architecture for sick kids: Concepts of environmental and architectural factors in child and adolescent psychiatry. Z. Kinder-Jugendpsychiatr. Psychother. 2019, 47, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Sommerhalder, K.; Abel, T. Landscape and well-being: A scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picton, C.; Fernandez, R.; Moxham, L.; Patterson, C. Experiences of outdoor nature-based therapeutic recreation programs for persons with a mental illness a qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2019, 17, 2517–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettany-Saltikov, J. How to Do a Systematic Literature Review in Nursing: A Step-by-Step Guide, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill Open University Press: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eplov, L.F.; Korsbek, L.; Peterson, L.; Olander, M. (Eds.) Psykiatrisk & Psykosocial Rehabilitering: En Recoveryorienteret Tilgang, 1st ed.; Munksgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Donald, F.; Duff, C.; Lee, S.; Kroschel, J.; Kulkarni, J. Consumer perspectives on the therapeutic value of a psychiatric environment. J. Ment. Health 2015, 24, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbino, C.; Toccolini, A.; Vagge, I.; Ferrario, P.S. Guidelines for the design of a healing garden for the rehabilitation of psychiatric patients. J. Agric. Eng. 2015, 46, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidl, S.; Mitchell, D.M.; Creighton, C.L. Outcomes of a Therapeutic Gardening Program in a Mental Health Recovery Center. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 2017, 33, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, H.C.; Ayala, L.; Schneider, A.; Wicks, N.; Levine-Dickman, A.; Clinton, S. Gardening on a psychiatric inpatient unit: Cultivating recovery. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 33, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wästberg, B.A.; Harris, U.; Gunnarsson, A.B. Experiences of meaning in garden therapy in outpatient psychiatric care in Sweden. A narrative study. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 28, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C.; Sachs, N. Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outsdoor Spaces; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, L.E. Mental Health Care Experiences: Listening to Families. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2004, 10, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Exposure | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatr* department Psychiatr* ward Psychiatr* unit Psychiatr* hospital Psychiatr* diagnosis Mental disease Mental disorder Mental illness | Garden Land use Outdoor Green space Healing garden Horticultural therapy Nature Universal design Architecture Healing architecture Therapeutic landscapes Health care | Rehabilitated Recovered Recovery Recovering Rehabilitation Rehabilitate Rehabilitation process Rehabilitation program Rehabilitation treatment Resocialization therapy Resocialization |

| - References - 1st Author, - Year of Publication—Country of Publication | Study Design Quantitative: Cross- Sectional/Longitudinal, Qualitative: Retrospective/ Prospective) | Study Population Characteristics: - N - Age - Sex Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| [27] Donald et al., 2015, Australia | Mixed methods Prospective: present study in existing environment. Semi-structured interview and focus group | Patients from a psychiatric department. N: 20 (9/11) Focus group: five women, four men. Semi-structured interview: six women, five men. Age: NA Sex: nine male, 11 female |

| [28] Erbino et al., 2015, Italy | Mixed methods Prospective: present study in existing environment. Case study: insights from patients, staff, and design professionals. Interviews and quantitative questionnaires with 100 participants (longitudinal | Patients with schizophrenia, personality disorders, severe depression N: 100 Age: 20 + Sex: NA |

| [29] Smidl et al. 2017, USA | Mixed methods Prospective: present study in existing environment. Semi-structured interviews and quantitative rating scales based on the Model of Human Occupation | Patients with mood disorders, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatric diagnoses were concurrent with medical conditions. N: 20 Age: 26–72 years old. Sex: NA |

| [30] Pieters et al., 2018, USA | Qualitative Prospective study of the experiences of psychiatric inpatients. Semi-structured interview | Participants with major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, PTSD N = 25 patients: Age: Average 28 years old. Sex: 14 women, 11 men. |

| [31] Wästberg et al., 2020, Sweden | Qualitative Prospective: participant perspectives and experiences during garden therapy. Narrative individual interviews | Participants: Able to participate in garden therapy. Sick due to common mental disorders. Two different social groups. N: 8 Age: 32–61 years old. Sex: one male, 7 female |

| References | Aim/Approach | Treatment, Setting and/or Activity | Indicators Related to Mental Health | Results/ Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [27] | To investigate the role of places in mediating recovery by addressing the environmental impact of hospital-based settings | A Low Dependency Unit and secure High Dependency Unit. A mixture of recreational and therapeutic activities | Well-being | The importance of staff; lack of clear architectural identity resulting in confused or confusing space; and limited amenity due to poor architectural design |

| [28] | To create a master plan for healing gardens, applied to a case study. How contact between human and nature/cultivating a healing garden can improve mental and physical well-being | Natural elements, a variety of spaces, lawns, flowerbeds, tree-lined avenues, shrubbery. Garden activity, rehabilitation program | Mental and spiritual well-being Stress reduction for patients, staff, and relatives Increased autonomy (patients)Reduction in care cost Improved mood Quality of life | Designing of green healing areas requires consideration of key issues such as: contact with nature, patient autonomy and ease of orientation, patient safety and comfort, possibility of choosing between places and functions |

| [29] | To explore the value of a therapeutic gardening project as part of the psychosocial recovery curriculum provided at a community mental health centre. | A community mental health centre. Activities were organized in four phases: ‘planning, construction of raised-bed gardens, maintenance of the gardens, and harvest. | Pride and self-worth Happiness Connecting past and present Socialization, peer support Decreased isolation Personal and social responsibility Need of less structure, encouragement | The Recovery Garden project provided an opportunity for clients with severe mental illness to demonstrate choice, initiative, self-direction, and collaboration within a new healthy occupation |

| [30] | To explore and describe the experiences of gardening in an acute psychiatric inpatient setting in the participants’ own words. A way to implement the Recovery Model to identify with and build skills to work towards finding new meaning and occupations | Weekly garden group, initiated by occupational therapists and implemented as an intervention by the unit’s multidisciplinary team | Ability to concentrate and relax Feeling calm Cognition Improved mood Distractions Productivity Decreased feeling of being isolated Ability to take on new information Sense of freedom Feeling energized Sense of belonging | Key elements to conducting a gardening group to ensure optimal results: format and structure of the group, activities such as ‘turning the soil,’ ‘watering…’, staff involvement, social interactions, experiences with nature, sensory perceptions, experiences of being, being grounded, finding focus |

| [31] | To serve as a complement to regular out-patient psychiatric care for clients with CMD to enhance their well-being. The study investigates whether and why participants perceive garden therapy as meaningful | An out-patient psychiatric clinic in Sweden Various garden activities | Senses of restoration Being in the moment Senses of belonging Feeling supported Togetherness Stress relief Feeling safe and accepted Quality of life | Garden therapy perceived as being meaningful, but different needs and prerequisites influenced what specific components in the garden therapy they perceived as meaningful |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hjort, M.; Mau, M.; Høj, M.; Roessler, K.K. The Importance of the Outdoor Environment for the Recovery of Psychiatric Patients: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032240

Hjort M, Mau M, Høj M, Roessler KK. The Importance of the Outdoor Environment for the Recovery of Psychiatric Patients: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032240

Chicago/Turabian StyleHjort, Mikkel, Martin Mau, Michaela Høj, and Kirsten K. Roessler. 2023. "The Importance of the Outdoor Environment for the Recovery of Psychiatric Patients: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032240

APA StyleHjort, M., Mau, M., Høj, M., & Roessler, K. K. (2023). The Importance of the Outdoor Environment for the Recovery of Psychiatric Patients: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032240