A Cross-Sectional Survey of Different Types of School Bullying before and during COVID-19 in Shantou City, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Models

2.5. Measurement

2.5.1. Bullying Questionnaires

2.5.2. Risk Behaviors Questionnaires

2.6. Statistical Analysis

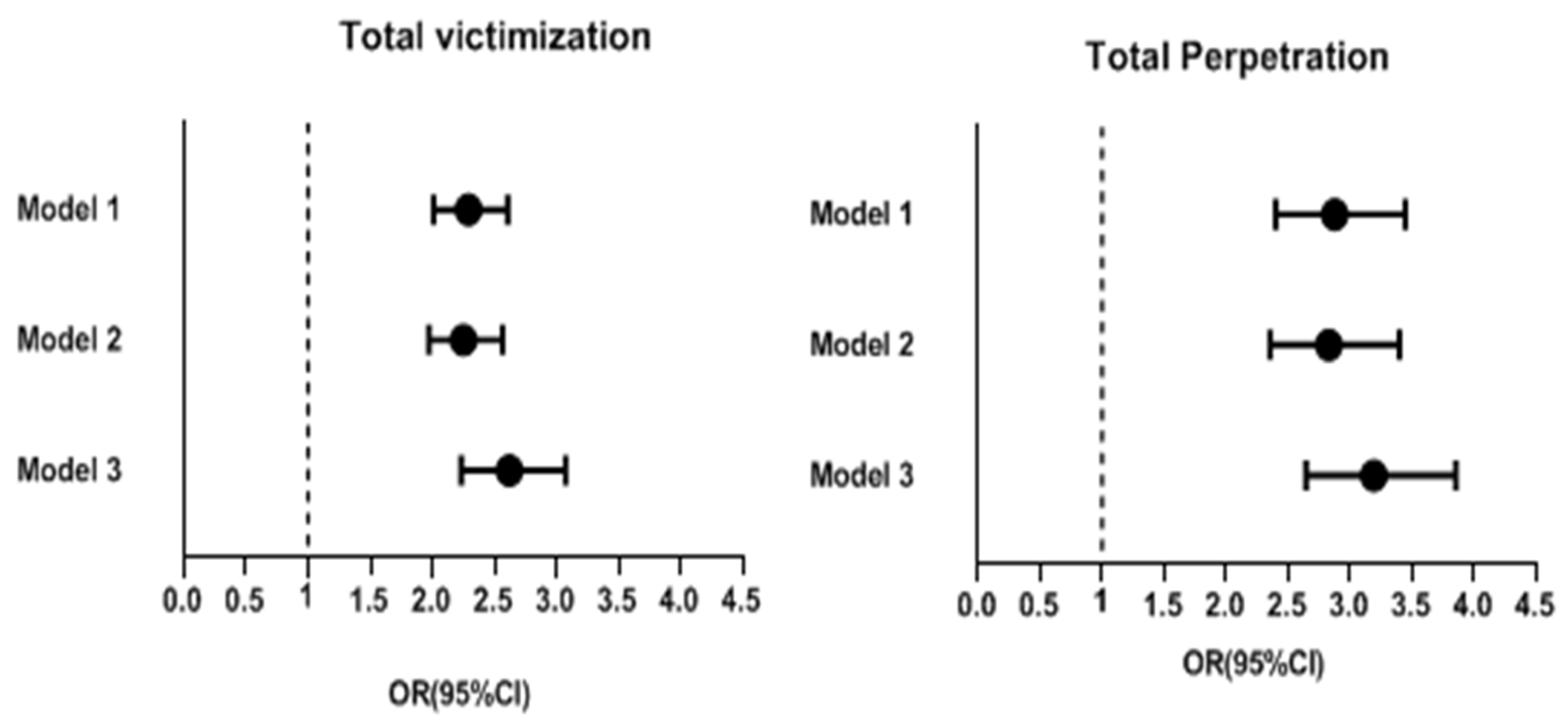

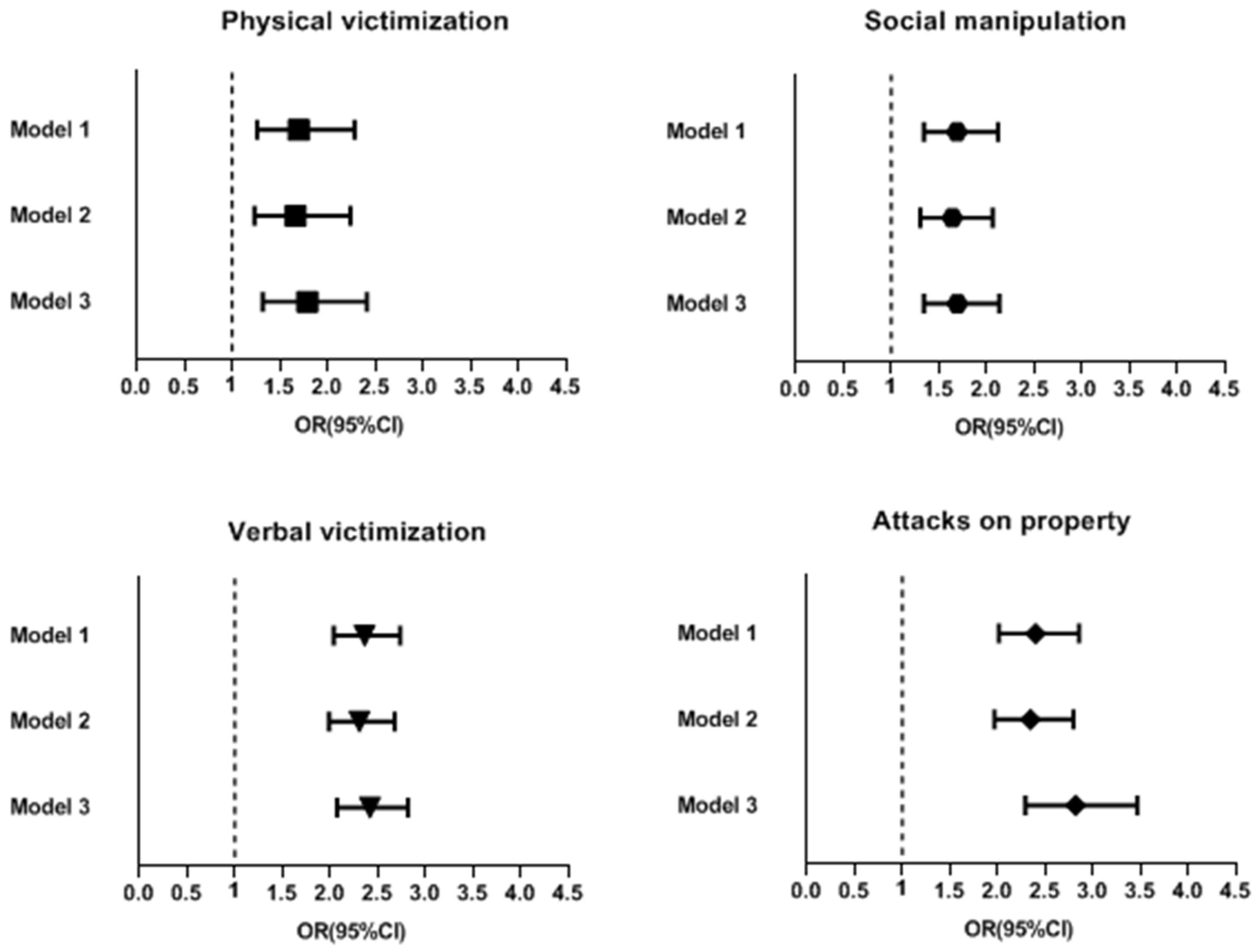

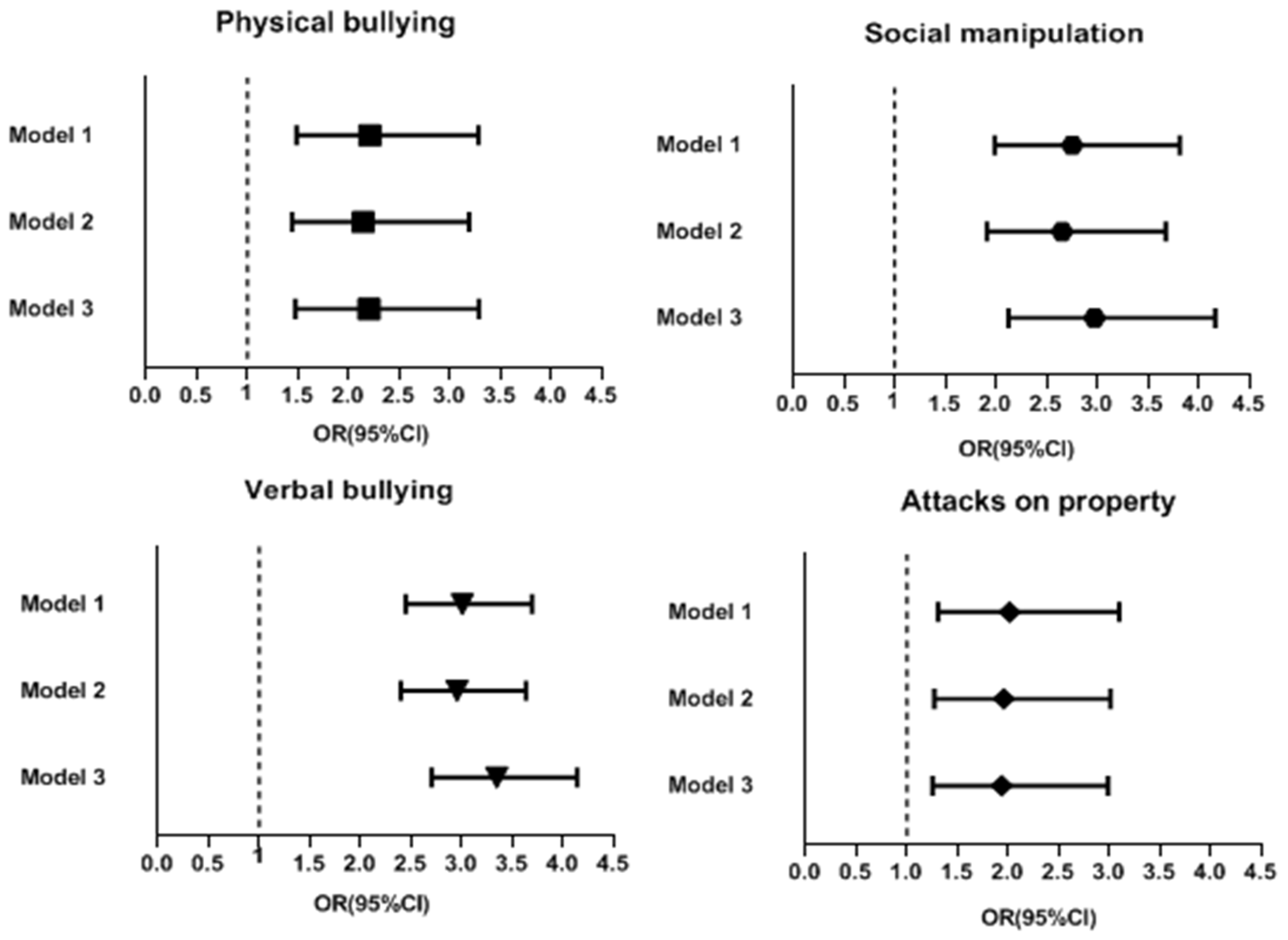

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Increases in the Incidence of Bullying Victimization and Perpetration during the Pandemic

4.2. Strengths

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Mahmoud, I.M.; Alruwaili, A.H.H.; Alsharif, M.M.; AlQubali, H.F.; Alsharif, Z.A.N.; Alanazi, W.K.A.; Alsharif, S.A.S.; Alruwaili, K.S.M.; Alanazi, K.A.I.; Alanazi, W.A.H. Management of Adolescent Malnutrition with Physical Exercise: Systematic review. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 11, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Fang, J.; Wan, Y.; Tao, F.; Sun, Y. Assessment of Mental Health of Chinese Primary School Students Before and After School Closing and Opening During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2021482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Ye, M.; Fu, Y.; Yang, M.; Luo, F.; Yuan, J.; Tao, Q. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teenagers in China. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, K.E.; Szkody, E.; Aggarwal, P.; Peterman, A.H.; Washburn, J.J.; Selby, E.A. Characterizing changes in mental health-related outcomes for health service psychology graduate students during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 2281–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, P.; Narasimha, V.L. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on alcohol use disorders and complications. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM Mon. J. Assoc. Physicians 2020, 113, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, S.; Tunmore, J.; Wajid Ali, M.; Ayub, M. Suicide, self-harm and suicidal ideation during COVID-19: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 306, 114228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olweus, D. School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 751–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D.; Limber, S.P. Bullying in school: Evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smokowski, P.R.; Kopasz, K.H. Bullying in School: An Overview of Types, Effects, Family Characteristics, and Intervention Strategies. Child. Sch. 2005, 27, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, M.; Eyuboglu, D.; Pala, S.C.; Oktar, D.; Demirtas, Z.; Arslantas, D.; Unsal, A. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying: Prevalence, the effect on mental health problems and self-harm behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 297, 113730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolke, D.; Lereya, S.T. Long-term effects of bullying. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lereya, S.T.; Copeland, W.E.; Costello, E.J.; Wolke, D. Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: Two cohorts in two countries. Lancet. Psychiatry 2015, 2, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Koh, Y.J.; Leventhal, B. School bullying and suicidal risk in Korean middle school students. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singham, T.; Viding, E.; Schoeler, T.; Arseneault, L.; Ronald, A.; Cecil, C.M.; McCrory, E.; Rijsdijk, F.; Pingault, J.B. Concurrent and Longitudinal Contribution of Exposure to Bullying in Childhood to Mental Health: The Role of Vulnerability and Resilience. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dake, J.A.; Price, J.H.; Telljohann, S.K. The nature and extent of bullying at school. J. Sch. Health 2003, 73, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, A.P.; Astolfi, R.C.; Leite, M.A.; Papa, C.H.G.; Ryngelblum, M.; Eisner, M.; Peres, M.F.T. Victims, bullies and bully-victims: Prevalence and association with negative health outcomes from a cross-sectional study in São Paulo, Brazil. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Pepler, D.; Craig, W.; Taradash, A. Dating experiences of bullies in early adolescence. Child Maltreatment 2000, 5, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.B.R.; Smokowski, P.R.; Rose, R.A.; Mercado, M.C.; Marshall, K.J. Cumulative Bullying Experiences, Adolescent Behavioral and Mental Health, and Academic Achievement: An Integrative Model of Perpetration, Victimization, and Bystander Behavior. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 2415–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P.; Lösel, F. School bullying as a predictor of violence later in life: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menesini, E.; Salmivalli, C. Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R. Bullying in children: Impact on child health. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e000939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, L.R.; Houston, J.E.; Steer, O.L. Development of the multidimensional peer victimization scale–revised (MPVS-R) and the multidimensional peer bullying scale (MPVS-RB). J. Genet. Psychol. 2015, 176, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piek, J.P.; Barrett, N.C.; Allen, L.S.; Jones, A.; Louise, M. The relationship between bullying and self-worth in children with movement coordination problems. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 75, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Koh, Y.J.; Leventhal, B.L. Prevalence of school bullying in Korean middle school students. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieno, A.; Gini, G.; Santinello, M. Different forms of bullying and their association to smoking and drinking behavior in Italian adolescents. J. Sch. Health 2011, 81, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Iannotti, R.J.; Nansel, T.R. School bullying among adolescents in the United States: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolliffe, D.; Farrington, D.P. Is low empathy related to bullying after controlling for individual and social background variables? J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, S.K.; O’Donnell, L.; Stueve, A.; Coulter, R.W. Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: A regional census of high school students. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, M.V.; Ovejero, A. Adolescents’ Attitudes to Bullying and its Relationship to Perceived Family Social Climate. Psicothema 2021, 33, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W.A.; Silva, J.L.D.; Sampaio, J.M.C.; Silva, M.A.I. Students’ health: An integrative review on family and bullying. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2017, 22, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y. Does Friend Support Matter? The Association between Gender Role Attitudes and School Bullying among Male Adolescents in China. Children 2022, 9, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menken, M.S.; Isaiah, A.; Liang, H.; Rivera, P.R.; Cloak, C.C.; Reeves, G.; Lever, N.A.; Chang, L. Peer victimization (bullying) on mental health, behavioral problems, cognition, and academic performance in preadolescent children in the ABCD Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 925727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynard, H.; Joseph, S. Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggress. Behav. Off. J. Int. Soc. Res. Aggress. 2000, 26, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at school. Basic facts and an effective intervention programme. Promot. Educ. 1994, 1, 27–31, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, D.; Moore, K.A. The Use of Likert Scales With Children. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaillancourt, T.; Brittain, H.; Krygsman, A.; Farrell, A.H.; Landon, S.; Pepler, D. School bullying before and during COVID-19: Results from a population-based randomized design. Aggress. Behav. 2021, 47, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Jiang, P.; Wu, Q.; Lai, X.; Liang, Y. Governmental Inter-sectoral Strategies to Prevent and Control COVID-19 in a Megacity: A Policy Brief From Shanghai, China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 764847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, C.; Yao, L.; Xu, L.; Chen, G.; Liao, Z.; Zhu, X.; Yang, W.; Li, W. COVID-19 outbreak prevention by early containment in Shantou, China. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.H.; Tang, X.; Luo, Y.T.; Zhang, M.; Feng, Z.P. Effects of policies and containment measures on control of COVID-19 epidemic in Chongqing. World J. Clin. Cases 2020, 8, 2959–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, N.; Kim, Y.; Saito, M.; Fujishiro, S. People’s worry about long-term impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. Asian J. Psychiatry 2022, 75, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Nunkoo, R.; Sunnassee, V.A.; Chen, X. Rethinking Lockdown Policies in the Pre-Vaccine Era of COVID-19: A Configurational Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fjermestad, K.W.; Orm, S.; Silverman, W.K.; Cogo-Moreira, H. Short report: COVID-19-related anxiety is associated with mental health problems among adults with rare disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 123, 104181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.R.; Caplan, R.D.; Van Harrison, R. Person-environment fit theory. Theor. Organ. Stress 1998, 28, 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hlremath, P.; Suhas, C.S.S.; Manjunath, M.; Shettar, M. COVID 19: Impact of lock-down on mental health and tips to overcome. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernanda Coello, M.; Valero-Moreno, S.; Sebastian Herrera, J.; Lacomba-Trejo, L.; Perez-Marin, M. Emotional Impact in Adolescents in Ecuador Six Months after the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Psychol. 2022, 156, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Han, Y.; Park, M.; Roh, S. Psychological, family, and social factors linked with juvenile theft in Korea. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2015, 36, 648–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.; Loeber, R.; Pardini, D. Parental Involvement in the Criminal Justice System and the Development of Youth Theft, Marijuana Use, Depression, and Poor Academic Performance. Criminology 2012, 50, 255–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Gilbert, J.E.; Thomas, K.M. Inhibitory control during emotional distraction across adolescence and early adulthood. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 1954–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosslin, K.; Golman, M. “Maybe you don’t want to face it”—College students’ perspectives on cyberbullying. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C.P.; Simmers, M.M.; Roth, B.; Gentile, D. Comparing cyberbullying prevalence and process before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 161, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafin, L.; Kusiak, A.; Czarkowska-Pączek, B. The COVID-19 Pandemic Increased Burnout and Bullying among Newly Graduated Nurses but Did Not Impact the Relationship between Burnout and Bullying and Self-Labelled Subjective Feeling of Being Bullied: A Cross-Sectional, Comparative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabah, A.; Aljaberi, M.A.; Lin, C.Y.; Chen, H.P. The Associations between Sibling Victimization, Sibling Bullying, Parental Acceptance-Rejection, and School Bullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchante, M.; Coelho, V.A.; Romao, A.M. The influence of school climate in bullying and victimization behaviors during middle school transition. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 71, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable * | Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying Victimization n (%) | Bullying Perpetration n (%) | Bullying Victimization n (%) | Bullying Perpetration n (%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 285 (18.47) | 146 (9.46) | 509 (34.74) | 313 (21.37) |

| Female | 167 (11.41) | 40 (2.73) | 259 (20.79) | 111 (8.91) |

| School | ||||

| Junior High School | 255 (16.31) | 104 (6.65) | 470 (30.26) | 260 (16.74) |

| High School | 197 (13.06) | 82 (5.44) | 298 (25.73) | 164 (14.16) |

| Drinking | ||||

| No | 405 (14.37) | 140 (4.97) | 672 (26.98) | 356 (14.29) |

| Yes | 47 (20.26) | 46 (19.83) | 96 (43.64) | 68 (30.91) |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | 427 (14.51) | 162 (5.51) | 733 (27.79) | 393 (14.90) |

| Yes | 25 (23.15) | 24 (22.22) | 35 (47.95) | 31 (42.47) |

| Playing violent video games | ||||

| No | 160 (10.61) | 45 (2.98) | 369 (22.12) | 158 (9.47) |

| Yes | 292 (19.52) | 141 (9.43) | 399 (37.89) | 266 (25.26) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, L.; Da, Q.; Huang, J.; Peng, Z.; Li, L. A Cross-Sectional Survey of Different Types of School Bullying before and during COVID-19 in Shantou City, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032103

Xie L, Da Q, Huang J, Peng Z, Li L. A Cross-Sectional Survey of Different Types of School Bullying before and during COVID-19 in Shantou City, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032103

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Linlin, Qingchen Da, Jingyu Huang, Zhekuan Peng, and Liping Li. 2023. "A Cross-Sectional Survey of Different Types of School Bullying before and during COVID-19 in Shantou City, China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032103

APA StyleXie, L., Da, Q., Huang, J., Peng, Z., & Li, L. (2023). A Cross-Sectional Survey of Different Types of School Bullying before and during COVID-19 in Shantou City, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032103