“Maybe it’s Not Just the Food?” A Food and Mood Focus Group Study

Abstract

1. Maybe it’s Not Just the Food? A Food and Mood Focus Group Study

1.1. Food, Mood, and Meaning

1.2. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Data Collection

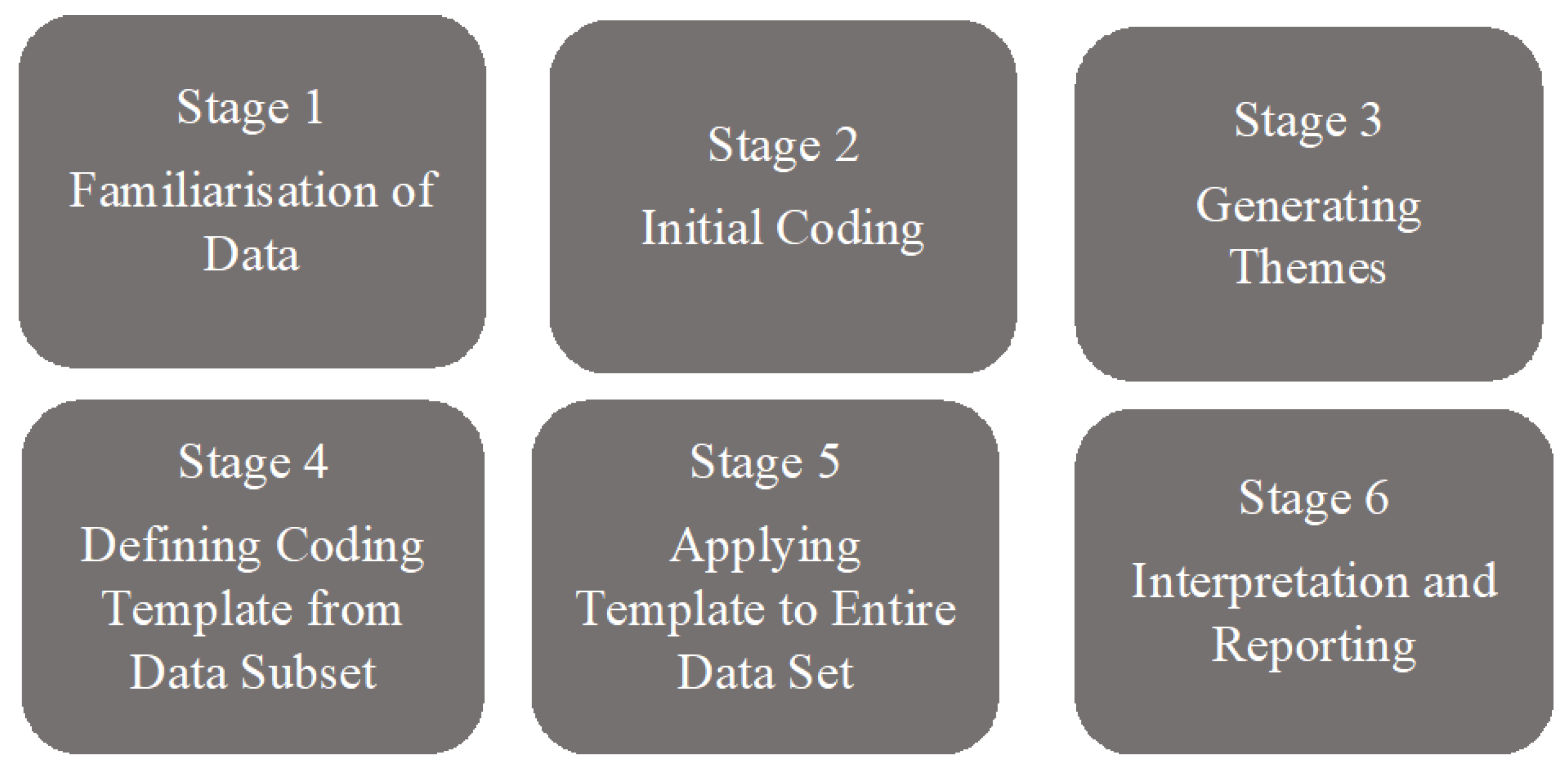

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Theme One—Social Context: Familial and Cultural Influences in Food and Mood

Maybe it’s not just the food? There’s a whole environment and the context in which you’re in. I think it really makes a difference if you’re in some kind of a family system, or you’re not. I think part of mood, if I’m not being too analytical, is, maybe with feeling ready, feeling prepared, feeling organised. To me, that’s where the comfort level is. Way beyond my own personal tastes for food. Eating with my family makes me happy, despite what foods are being served. Preparing and sharing meals together is a way we express our love and gratitude towards each other.(Mary)

As far as mood is concerned, I can eat the healthiest diet in the world, in complete isolation. Say if I pack myself this beautiful organic lunch, and it’s got probiotics from the kefir and sauerkraut and all my organic greens, and I go to work in a cubicle, and I don’t talk to anyone. I just sit down at my desk all day and eat lunch at my computer. I just think I’m going to get sick. I don’t think. I’m going to be well. When I eat away from my desk surrounded by others, even if the food itself is not as healthy, I tend to feel more uplifted once I return to my desk.(Vicki)

Every time I come into a situation that’s highly emotional. I just stuff my face. My Mum doesn’t deal with emotions. If you’re upset, she’ll bring around a cheesecake (laughs) and two spoons. I think a lot of times they don’t know how to comfort and that’s where my Mum brings a cake…... She won’t even give you a hug, so uncomfortable. But she will eat a cake with you. That’s her hug. We know where it’s coming from, a place of love. But it was the way she was raised as well.(Amy)

3.2. Theme Two—Social Economics: Time, Finance, and Food Security

I’d make homemade pizzas, we did the base, and we could all put what we liked on them. But that would take me like an hour and a half of making the dough and rolling it out. It’s about time restraints as well, families who work and then pick up kids and then get home, and it’s not just about cost, it’s about the cost of time.(Katherine)

I wouldn’t say I’m a food prepper…… sometimes I try, but I find that too boring and too overwhelming. I tend to make lunch at the same time as dinner. If I’m making dinner for my boyfriend. I’m going to make our lunches……… If I’m making this now, I’m just gonna do it double. I always make sure there’s leftovers, put it in the lunch boxes, ready to go. I found that if I didn’t, it would be too hard in the morning. I wouldn’t even be able to stomach the idea of lunch at that time. I would just end up wasting all this money buying stuff out and not feeling that good about it.(Sarah)

It takes extra time if you’re going to eat well and prepare well and plan well. I think we all know; if you’re tired or fatigued, it’s too hard to think, you can’t be bothered. You just go and grab whatever, which keeps you in that cycle, and when you’re feeling down, and then you’re tired, you’re like, “I’ll just grab something else.” Now you’re more tired and down. I’ve made all these decisions during the day. I think that’s the hardest part. The whole day like, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick and then you just get to the night and you’re like—well I just had to eat the whole packet of chips.(Mary)

When do you find time to cook? To go shopping, get your whole foods and then go home and cook them and participate in some social activity like soccer? It’s hard, working full time, studying full time, being a parent, and managing time. It’s not so much an emotional thing. It’s more like, I just am spread thin. I’ve got the kids, and I’m like okay, you want frozen pizza for dinner? Hey, let’s just have frozen pizza for dinner. It’s the time thing for me. I would love if I had the energy to always walk into a perfectly clean kitchen. I would love to cook a healthy meal and have healthy snacks around for the kids, me, and everybody, but it’s the time really.(Sophie)

3.3. Theme Three—Food Nostalgia: Unlocking Memories That Impact Mood

I think there are certain things that are comfort, whether it’s a particular food group, or it’s a memory of a food. If you had something that was wonderful when you were a kid, and you associate food with a wonderful time and you just want to go back there. My Mum always loved jam and cream. You’d have a slice of bread, no butter, jam, and then whipped cream on top, and that was her go-to. I lost her 18 months ago, so I’ve been having this periodically, because it’s what Mum wanted. So that’s the other element of food and mood—because it is memory that connects you to those you love.(Sarah)

Growing up, my mother, who has now passed, cooked desserts. I have strong feelings associated with these foods, and they take me back to my childhood and make me feel comforted. I just need cream. If I have any sort of cake even if it’s cheesecake creamy, I’ll have to have a big glob of cream. This was my mother as well. She was the same.(Layla)

I love cooking. So, I get really excited when I start cooking …. Because my father lives in Greece and I cook there with my Mum and my Dad. It brings me in touch with those moments. So that’s really motivating. I get really happy when I’m cooking. I love having a glass of wine and chuck on the music and there’s a great atmosphere. It’s a big event for me every time I cook, because it makes me feel like I am there with them.(Jonas)

4. Conclusions

Strengths and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Depression. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Wang, D.D.; Li, Y.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Rosner, B.A.; Sun, Q.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Rimm, E.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Stampfer, M.J.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and mortality: Results from 2 prospective cohort studies of US men and women and a meta-analysis of 26 cohort studies. Circulation 2021, 143, 1642–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a healthy diet: Evidence for the role of contemporary dietary patterns in health and disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacka, F.N. Nutritional psychiatry: Where to next? EBioMedicine 2017, 17, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, W.; Lane, M.M.; Hockey, M.; Aslam, H.; Walder, K.; Borsini, A.; Firth, J.; Pariante, C.M.; Berding, K.; Cryan, J.F.; et al. Diet and depression: Future needs to unlock the potential. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 778–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G. Nutritional psychiatry: How diet affects brain through gut microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, R.A.H.; van der Beek, E.M.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Cryan, J.F.; Hebebrand, J.; Higgs, S.; Schellekens, H.; Dickson, S.L. Nutritional psychiatry: Towards improving mental health by what you eat. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zeng, L.; Zou, K.; Shan, S.; Wang, X.; Xiong, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, G. Role of dietary factors in the prevention and treatment for depression: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective studies. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.; Sotoudeh, G.; Majdzadeh, R.; Nejati, S.; Darabi, S.; Raisi, F.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Sorayani, M. Healthy and unhealthy dietary patterns are related to depression: A case-control study. Psychiatry Investig. 2015, 12, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassale, C.; Batty, G.D.; Baghdadli, A.; Jacka, F.N.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Akbaraly, T.N. Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jacka, F.N.; Neil, A.; Opie, R.S.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Cotton, S.; Mohebbi, M.; Castle, D.; Dash, S.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Chatterton, M.; et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the SMILES trial). BMC Med. 2017, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parletta, N.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Cho, J.; Wilson, A.; Bogomolova, S.; Villani, A.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Niyonsenga, T.; Blunden, S.; Meyer, B.; et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr. Neurosci. 2017, 22, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, H.M.; Stevenson, R.J.; Chambers, J.R.; Gupta, D.; Newey, B.; Lim, C.K. A brief diet intervention can reduce symptoms of depression in young adults—A randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 0222768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayes, J.; Schloss, J.; Sibbritt, D. A randomised controlled trial assessing the effect of a Mediterranean diet on the symptoms of depression in young men (the ‘AMMEND’ study): A study protocol. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Solmi, M.; Wootton, R.E.; Vancampfort, D.; Schuch, F.B.; Hoare, E.; Gilbody, S.; Torous, J.; Teasdale, S.B.; Jackson, S.E.; et al. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: The role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Marx, W.; Dash, S.; Carney, R.; Teasdale, S.B.; Solmi, M.; Stubbs, B.; Schuch, F.B.; Carvalho, A.F.; Jacka, F.; et al. The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom. Med. 2019, 81, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis, J. Unreformed nutritional epidemiology: A lamp post in the dark forest. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houwen, L. Food for Mood: A Study to Unravel Our Moody Food Interactions. Masters Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, E.; Stewart-Knox, B.; Rowland, I. A qualitative analysis of consumer perceptions of mood, food and mood-enhancing functional foods. J. Nutraceuticals Funct. Med. Foods 2005, 4, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds, J.; Keith, R.; Woloshynowych, M. Food and mood: Exploring the determinants of food choices and the effects of food consumption on mood among women in Inner London. World Nutr. 2020, 11, 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcott, A. The cultural significance of food and eating. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1982, 41, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Monaco, G.; Bonetto, E. Social representations and culture in food studies. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allsop, J. Competing paradigms and health research: Design and process. In Researching Health: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods; Saks, M., Allsop, J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hok-Eng Tan, F. Flavours of thought: Towards A phenomenology of food-related experiences. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst. 2013, 11, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.F.; Bradbury, J.; Yoxall, J.; Sargeant, S. “Its about what you’ve assigned to the salad” focus group discussions on the relationship between food and mood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.C.; Kromm, E.E.; Brown, N.A.; Klassen, A.C. “I come from a black-eyed pea background”: The Incorporation of history into women’s discussions of diet and health. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2012, 51, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Weber, M.B. What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qual Health Res. 2019, 29, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, L. Intimate reflections: Private diaries in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2011, 11, 664–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.; McCluskey, S.; Turley, E.; King, N. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2015, 12, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, 12. 2018. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/support-services/nvivo-downloads (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Themes and codes. In Applied Thematic Analysis; Guest, G., MacQueen, K.M., Namey, E.E., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2012; pp. 49–79. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, S.; Thomas, J. Social influences on eating. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, S. Social norms and their influence on eating behaviours. Appetite 2015, 86, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manninen, S.; Tuominen, L.; Dunbar, R.I.; Karjalainen, T.; Hirvonen, J.; Arponen, E.; Hari, R.; Jääskeläinen, I.P.; Sams, M.; Nummenmaa, L. Social laughter triggers endogenous opioid release in humans. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 6125–6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, E.; Launay, J.; Dunbar, R.I.M. The ice-breaker effect: Singing mediates fast social bonding. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015, 2, 150221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarr, B.; Launay, J.; Cohen, E.; Dunbar, R. Synchrony and exertion during dance independently raise pain threshold and encourage social bonding. Biol. Lett. 2015, 11, 20150767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunbar, R.I.M. Breaking bread: The functions of social eating. Adapt. Hum. Behav. Physiol. 2017, 3, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germov, J.; Williams, L. A Sociology of Food and Nutrition: The Social Appetite; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, G.; Adan, R.A.; Belot, M.; Brunstrom, J.M.; de Graaf, K.; Dickson, S.L.; Hare, T.; Maier, S.; Menzies, J.; Preissl, H. The determinants of food choice. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.F.; Maughan, D.L.; Grant-Peterkin, H. Interconnected or disconnected? Promotion of mental health and prevention of mental disorder in the digital age. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerster, K.D.; Wilson, S.; Nelson, K.M.; Reiber, G.E.; Masheb, R.M. Diet quality is associated with mental health, social support, and neighborhood factors among Veterans. Eat. Behav. 2016, 23, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Economics. The Sainsbury’s Living Well Index. 2018. Available online: https://www.about.sainsburys.co.uk/~/media/Files/S/Sainsburys/living-well-index/Sainsburys%20Living%20Well%20Index%20Wave%204%20Jun%202019%20FV.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Farmer, N.; Touchton-Leonard, K.; Ross, A. Psychosocial benefits of cooking interventions: A systematic review. Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 45, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.W.; Epel, E.S.; Ritchie, L.D.; Crawford, P.B.; Laraia, B.A. Food insecurity is inversely associated with diet quality of lower-income adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1943–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venn, D.; Dixon, J.; Banwell, C.; Strazdins, L. Social determinants of household food expenditure in Australia: The role of education, income, geography and time. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.W.; Zhou, M.S. Household food insecurity and the association with cumulative biological risk among lower-income adults: Results from the national health and nutrition examination surveys 2007–2010. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.F.; von der Heidt, T.; Bradbury, J.F.; Grace, S. How much more to pay? A study of retail prices of organic versus conventional vegetarian foods in an Australian regional area. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2021, 52, 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri, C.; Rogus, S. Food choices, food security, and food policy. J. Int. Aff. 2014, 67, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.A.; Park, E.-C.; Ju, Y.J.; Lee, T.H.; Han, E.; Kim, T.H. Breakfast consumption and depressive mood: A focus on socioeconomic status. Appetite 2017, 114, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, S.K. Comparing the Physical and Psychological Effects of Food Security and Food Insecurity. Senior. Honors Thesis, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.F.; Eather, R.; Best, T. Plant-based dietary quality and depressive symptoms in Australian vegans and vegetarians: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2021, 4, e000332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Bradbury, J.; Yoxall, J.; Sargeant, S. Is dietary quality associated with depression? An analysis of the Australian longitudinal study of women’s health data. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C.; Wildschut, T.; Baden, D. Nostalgia: Conceptual issues and existential functions. In Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology; Greenberg, J., Koole, L., Pyszczynski, T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, USA, 2004; pp. 200–214. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, C.A.; Green, J.D.; Buchmaier, S.; McSween, D.K.; Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C. Food-evoked nostalgia. Cogn. Emot. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignolles, A.; Pichon, P.-E. A taste of nostalgia: Links between nostalgia and food consumption. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2014, 17, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammers, L.; Wong, L.; Brown, R.; Price, S.; Ekinci, E.; Sumithran, P. Identifying stress-related eating in behavioural research: A review. Horm. Behav. 2020, 124, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C.; Wildschut, T. The sociality of personal and collective nostalgia. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 30, 123–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Waterfield, J. Focus group methodology: Some ethical challenges. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 3003–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Sparkes, A.C. Qualitative research. In Handbook of Sport Psychology; Tenenbaum, G., Eklund, R.C., Eds.; Wiley: Brisbane, Australia, 2020; pp. 999–1019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, M.F.; Angus, D.; Walsh, H.; Sargeant, S. “Maybe it’s Not Just the Food?” A Food and Mood Focus Group Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032011

Lee MF, Angus D, Walsh H, Sargeant S. “Maybe it’s Not Just the Food?” A Food and Mood Focus Group Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032011

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Megan F., Douglas Angus, Hayley Walsh, and Sally Sargeant. 2023. "“Maybe it’s Not Just the Food?” A Food and Mood Focus Group Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032011

APA StyleLee, M. F., Angus, D., Walsh, H., & Sargeant, S. (2023). “Maybe it’s Not Just the Food?” A Food and Mood Focus Group Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032011