Poor Cervical Cancer Knowledge and Awareness among Women and Men in the Eastern Cape Province Rural Community

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Study Setting, Population, and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2. Knowledge about Cervical Cancer and Its Risk Factors According to Gender

3.3. Knowledge about Cervical Cancer Prevention Methods According to Gender

3.4. Cervical Cancer Knowledge among Women According to Cervical Cancer Screening Status

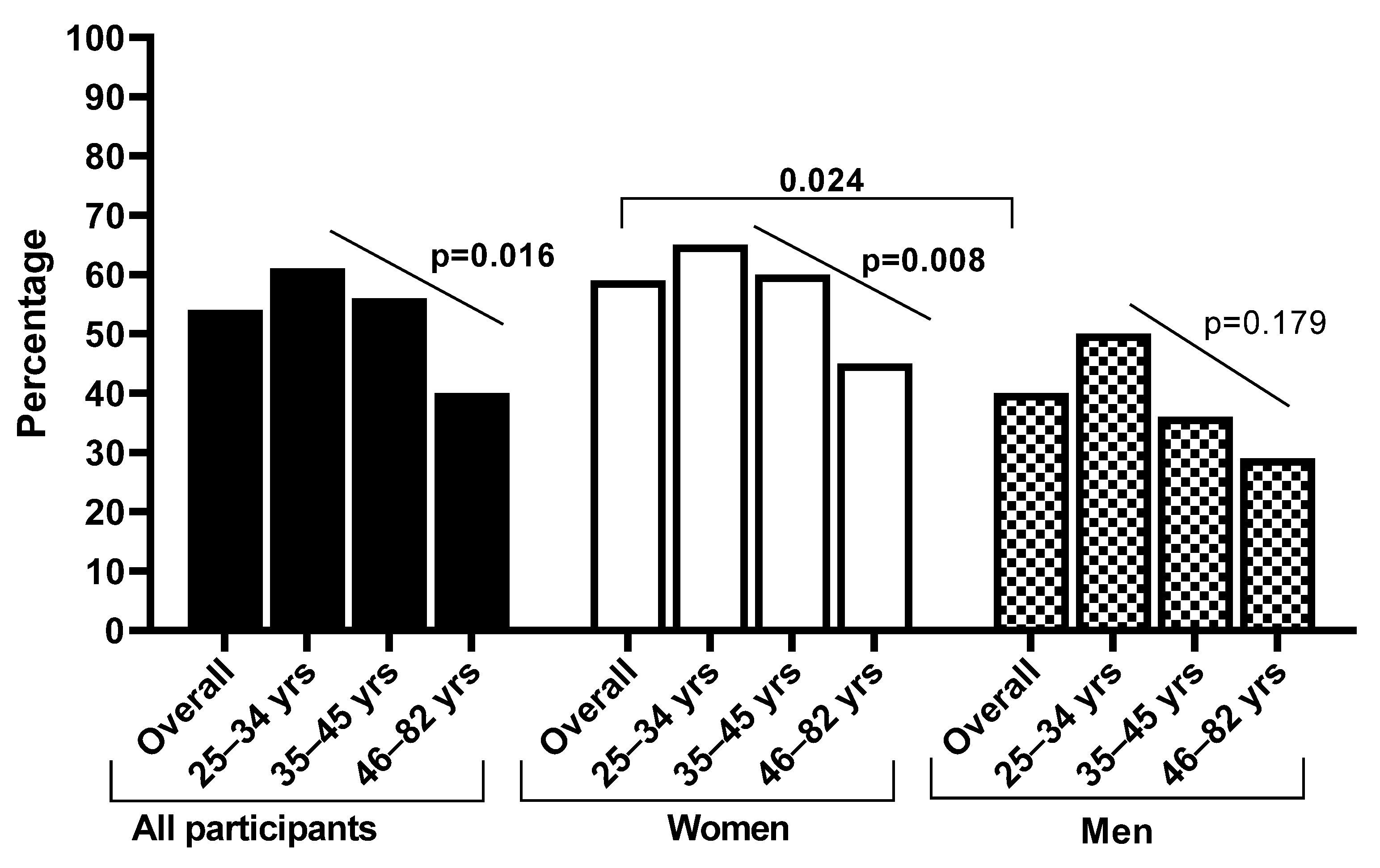

3.5. Cervical Cancer Knowledge Score among Women and Men

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength of the Study

4.2. Limitations of the Study

4.3. Expected Outcomes and Impact of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Serrano, B.; Mena, M.; Gómez, D.; Muñoz, J.; Bosch, F.; de Sanjosé, S. Summary Report 2023: Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in South Africa; ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre): Barcelona, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somdyala, N.I.; Bradshaw, D.; Dhansay, M.A.; Stefan, D.C. Increasing Cervical Cancer Incidence in Rural Eastern Cape Province of South Africa from 1998 to 2012: A Population-Based Cancer Registry Study. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stelzle, D.; Tanaka, L.F.; Lee, K.K.; Ibrahim Khalil, A.; Baussano, I.; Shah, A.S.V.; McAllister, D.A.; Gottlieb, S.L.; Klug, S.J.; Winkler, A.S.; et al. Estimates of the global burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e161–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboumba Bouassa, R.-S.; Prazuck, T.; Lethu, T.; Jenabian, M.-A.; Meye, J.-F.; Bélec, L. Cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: A preventable noncommunicable disease. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2017, 15, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- UNAIDS. Country Factsheets, South Africa. 2021. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Simms, K.T.; Steinberg, J.; Caruana, M.; Smith, M.A.; Lew, J.-B.; Soerjomataram, I.; Castle, P.E.; Bray, F.; Canfell, K. Impact of scaled up human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical screening and the potential for global elimination of cervical cancer in 181 countries, 2020–2099: A modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 394–407. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, F.; Loos, A.H.; McCarron, P.; Weiderpass, E.; Arbyn, M.; Møller, H.; Hakama, M.; Parkin, D.M. Trends in cervical squamous cell carcinoma incidence in 13 European countries: Changing risk and the effects of screening. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 677–686. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, M.; Richter, K. Cervical cancer prevention in South Africa: HPV vaccination and screening both essential to achieve and maintain a reduction in incidence. S. Afr. Med. J. 2015, 105, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Botha, M.; Dreyer, G. Guidelines for cervical cancer screening in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2017, 9, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Denny, L.; Cubie, H.; Bhatla, N. Expanding Prevention of Cervical Cancer in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. In Human Papillomavirus; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 379–388. [Google Scholar]

- Arbyn, M.; Verdoodt, F.; Snijders, P.J.; Verhoef, V.M.; Suonio, E.; Dillner, L.; Minozzi, S.; Bellisario, C.; Banzi, R.; Zhao, F.-H.; et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: A meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Dhokotera, T.; Asangbeh, S.; Bohlius, J.; Singh, E.; Egger, M.; Rohner, E.; Ncayiyana, J.; Clifford, G.M.; Olago, V.; Sengayi-Muchengeti, M. Cervical cancer in women living in South Africa: A record linkage study of the National Health Laboratory Service and the National Cancer Registry. Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitha, W.; Sibulawa, S.; Funani, I.; Swartbooi, B.; Maake, K.; Hellebo, A.; Hongoro, D.; Mnyaka, O.R.; Ngcobo, Z.; Zungu, C.M.; et al. A cross-sectional study of knowledge, attitudes, barriers and practices of cervical cancer screening among nurses in selected hospitals in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Ncane, Z.; Faleni, M.; Pulido-Estrada, G.; Apalata, T.R.; Mabunda, S.A.; Chitha, W.; Nomatshila, S.C. Knowledge on Cervical Cancer Services and Associated Risk Factors by Health Workers in the Eastern Cape Province. Healthcare 2023, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rangolo, N.; Tshitangano, T.G.; Olaniyi, F.C. Compliance of Professional Nurses at Primary Health Care Facilities to the South African Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiiti, T.A.; Bogers, J.; Lebelo, R.L. Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer among Women Attending Gynecology Clinics in Pretoria, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbulawa, Z.Z.; Somdyala, N.I.; Mabunda, S.A.; Williamson, A.-L. Effect of human papillomavirus (HPV) education intervention on HPV knowledge and awareness among high school learners in Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. J. Cancer Educ. 2021, 38, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadzange, E.E.; Peeters, A.; Joore, M.A.; Kimman, M.L. The effectiveness of health education interventions on cervical cancer prevention in Africa: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2022, 164, 107219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducray, J.F.; Kell, C.M.; Basdav, J.; Haffejee, F. Cervical cancer knowledge and screening uptake by marginalized population of women in inner-city Durban, South Africa: Insights into the need for increased health literacy. Women’s Health 2021, 17, 17455065211047141. [Google Scholar]

- Omoyeni, O.; Tsoka-Gwegweni, J. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of cervical cancer screening among rural women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 42, 188. [Google Scholar]

- Gwavu, Z.; Murray, D.; Okafor, U.B. Perception of Women’s Knowledge of and Attitudes towards Cervical Cancer and Papanicolaou Smear Screenings: A Qualitative Study in South Africa. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perlman, S.; Wamai, R.G.; Bain, P.A.; Welty, T.; Welty, E.; Ogembo, J.G. Knowledge and awareness of HPV vaccine and acceptability to vaccinate in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibako, P.; Hlongwa, M.; Tsikai, N.; Manyame, S.; Ginindza, T.G. Mapping Evidence on Management of Cervical Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9207. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.W.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, Y. Men’s awareness of cervical cancer: A qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Dsouza, J.P.; Van den Broucke, S.; Pattanshetty, S.; Dhoore, W. Factors explaining men’s intentions to support their partner’s participation in cervical cancer screening. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 443. [Google Scholar]

- de Fouw, M.; Stroeken, Y.; Niwagaba, B.; Musheshe, M.; Tusiime, J.; Sadayo, I.; Reis, R.; Peters, A.A.W.; Beltman, J.J. Involving men in cervical cancer prevention; a qualitative enquiry into male perspectives on screening and HPV vaccination in Mid-Western Uganda. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280052. [Google Scholar]

- Rwamugira, J.; Maree, J.E.; Mafutha, N. The knowledge of South African men relating to cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening. J. Cancer Educ. 2019, 34, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Amponsah-Dacosta, E.; Blose, N.; Nkwinika, V.V.; Chepkurui, V. Human papillomavirus vaccination in South Africa: Programmatic challenges and opportunities for integration with other adolescent health services? Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 799984. [Google Scholar]

- Boily, M.-C.; Barnabas, R.V.; Rönn, M.M.; Bayer, C.J.; van Schalkwyk, C.; Soni, N.; Rao, D.W.; Staadegaard, L.; Liu, G.; Silhol, R.; et al. Estimating the effect of HIV on cervical cancer elimination in South Africa: Comparative modelling of the impact of vaccination and screening. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 54, 101754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mokhele, I.; Evans, D.; Schnippel, K.; Swarts, A.; Smith, J.; Firnhaber, C. Awareness, perceived risk and practices related to cervical cancer and pap smear screening: A crosssectional study among HIV-positive women attending an urban HIV clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016, 106, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Mengesha, M.B.; Chekole, T.T.; Hidru, H.D. Uptake and Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening among Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive Women in Sub Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 338. [Google Scholar]

- Akokuwebe, M.E.; Idemudia, E.S.; Lekulo, A.M.; Motlogeloa, O.W. Determinants and levels of cervical Cancer screening uptake among women of reproductive age in South Africa: Evidence from South Africa Demographic and health survey data, 2016. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Li, S.; Ratcliffe, J.; Chen, G. Assessing knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer screening among rural women in Eastern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isabirye, A. Individual and intimate-partner factors associated with cervical cancer screening in Central Uganda. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutyaba, T.; Mirembe, F.; Sandin, S.; Weiderpass, E. Male partner involvement in reducing loss to follow-up after cervical cancer screening in Uganda. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2009, 107, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragan, K.R.; Buchanan Lunsford, N.; Lee Smith, J.; Saraiya, M.; Aketch, M. Perspectives of screening-eligible women and male partners on benefits of and barriers to treatment for precancerous lesions and cervical cancer in Kenya. Oncologist 2018, 23, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Participants, N = 252 | Women, N = 176 | Men, N = 76 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % | n | % | n | % | n | p-Value | |

| Age | 25–34 years | 40.5 | 102 | 40.3 | 71 | 40.8 | 31 | >0.999 |

| 35–45 years | 28.6 | 72 | 30.1 | 53 | 25.0 | 19 | 0.450 | |

| 46–82 years | 31.0 | 78 | 29.5 | 52 | 34.2 | 26 | 0.462 | |

| Education level | Primary (Grade 0–7) | 26.2 | 66 | 25.6 | 45 | 27.6 | 21 | 0.756 |

| Secondary (Grade 8–12) | 50.4 | 127 | 48.9 | 86 | 53.9 | 41 | 0.494 | |

| Tertiary | 23.4 | 59 | 25.6 | 45 | 18.4 | 14 | 0.258 | |

| Employment status | Employed | 37.7 | 95 | 31.3 | 55 | 52.6 | 40 | 0.002 |

| Unemployed | 59.9 | 151 | 66.5 | 117 | 44.7 | 34 | 0.002 | |

| Student | 2.4 | 6 | 2.3 | 4 | 2.6 | 2 | >0.999 | |

| Household income | <R1999 | 46.0 | 116 | 50.6 | 89 | 35.5 | 27 | 0.039 |

| R2000–R5000 | 29.0 | 73 | 29.5 | 52 | 27.6 | 21 | 0.880 | |

| R5001–R10000 | 8.7 | 22 | 6.3 | 11 | 14.5 | 11 | 0.050 | |

| >R10001 | 12.7 | 32 | 3.4 | 6 | 34.2 | 26 | <0.001 | |

| Missing data | 3.6 | 9 | 1.1 | 2 | 9.2 | 7 | 0.004 | |

| Done Pap smear? (only females) | Yes | 39.2 | 69 | |||||

| No | 60.2 | 106 | ||||||

| Missing data | 0.6 | 1 | ||||||

| Overall | Women | Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % | n | % | n | % | n | p-Value * | |

| How common is cervical cancer? | Very common to common * | 53.8 | 107 | 52.4 | 77 | 57.7 | 30 | 0.509 |

| Very rare to rare | 26.6 | 53 | 29.3 | 43 | 19.2 | 10 | 0.160 | |

| Do not know | 19.6 | 39 | 18.4 | 27 | 23.1 | 12 | 0.462 | |

| What causes cervical cancer? | HPV * | 43.2 | 86 | 43.4 | 66 | 38.5 | 20 | 0.421 |

| HIV | 13.1 | 26 | 13.8 | 21 | 9.6 | 5 | 0.479 | |

| TB | 3.0 | 6 | 2.6 | 4 | 3.8 | 2 | 0.381 | |

| Bacteria | 13.1 | 26 | 11.8 | 18 | 15.4 | 8 | 0.564 | |

| Do not know | 31.7 | 63 | 30.3 | 46 | 32.7 | 17 | 0.852 | |

| Early stages of cervical cancer do not have signs/symptoms | Yes | 26.6 | 53 | 27.9 | 41 | 23.1 | 12 | 0.500 |

| No * | 20.1 | 40 | 20.4 | 30 | 19.2 | 10 | 0.856 | |

| Do not know | 53.3 | 106 | 51.7 | 76 | 57.7 | 30 | 0.246 | |

| Signs/symptoms of cervical cancer | Pain during urination * | 43.2 | 86 | 49.0 | 72 | 26.9 | 14 | 0.006 |

| Excessive vaginal bleeding after sex * | 32.7 | 65 | 36.1 | 53 | 23.1 | 12 | 0.086 | |

| Vaginal itchiness | 20.1 | 52 | 32.0 | 47 | 9.6 | 5 | 0.007 | |

| Normal vaginal discharge | 13.1 | 26 | 17.0 | 25 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.006 | |

| Missing menstruation | 9.5 | 19 | 10.2 | 15 | 7.7 | 4 | 0.596 | |

| Don’t know | 39.2 | 78 | 32.0 | 47 | 40.4 | 21 | 0.272 | |

| Which of the following increases the risk of cervical cancer? | HPV infection * | 46.2 | 92 | 50.3 | 74 | 34.6 | 18 | 0.032 |

| Tuberculosis | 7.5 | 15 | 6.8 | 10 | 9.6 | 5 | 0.509 | |

| Frequent sex with one man | 13.1 | 26 | 13.6 | 20 | 11.5 | 6 | 0.704 | |

| Giving birth to one child | 3.5 | 7 | 4.8 | 7 | 0.0 | 0 | … | |

| Smoking * | 24.6 | 49 | 25.9 | 38 | 21.2 | 11 | 0.500 | |

| Family history of CC * | 10.1 | 20 | 10.9 | 16 | 7.7 | 4 | 0.511 | |

| HIV and other STIs * | 31.7 | 63 | 33.3 | 49 | 26.9 | 14 | 0.393 | |

| Early sexual activity * | 24.1 | 48 | 25.2 | 37 | 21.2 | 11 | 0.561 | |

| How common is HPV infection? | Very common * | 42.7 | 85 | 46.3 | 68 | 32.7 | 17 | 0.089 |

| Very rare | 26.6 | 53 | 25.9 | 38 | 28.8 | 15 | 0.675 | |

| Do not know | 30.7 | 61 | 27.9 | 41 | 38.5 | 20 | 0.155 | |

| HPV is transmitted by… | Sexual intercourse * | 61.8 | 123 | 65.3 | 96 | 51.9 | 27 | 0.089 |

| Skin-to-skin contact * | 1.5 | 3 | 0.7 | 1 | 3.8 | 2 | 0.168 | |

| Droplets or sneezing | 2.0 | 4 | 2.7 | 4 | 0.0 | 0 | … | |

| Contaminated surfaces | 5.0 | 10 | 5.4 | 8 | 3.8 | 2 | >0.999 | |

| By any forms | 0.5 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | … | |

| Do not know | 29.6 | 59 | 25.9 | 38 | 40.4 | 21 | 0.049 | |

| Is smoking a risk factor for cervical cancer? | Yes * | 53.3 | 106 | 52.4 | 77 | 55.8 | 29 | 0.674 |

| No | 11.6 | 23 | 14.3 | 21 | 3.8 | 2 | 0.043 | |

| Do not know | 35.2 | 70 | 33.3 | 49 | 40.4 | 21 | 0.360 | |

| Is having multiple sexual partners a risk factor for cervical cancer? | Yes * | 77.9 | 155 | 74.8 | 110 | 86.5 | 45 | 0.080 |

| No | 3.0 | 6 | 4.1 | 6 | 0.0 | 0 | … | |

| Do not know | 19.1 | 38 | 21.1 | 31 | 13.5 | 7 | 0.229 | |

| Overall | Women | Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % | n | % | n | % | n | p-Value * | |

| What test is used for cervical cancer screening? | Pap smear * | 53.8 | 107 | 58.5 | 86 | 40.4 | 21 | 0.024 |

| Urine test | 4.5 | 9 | 4.8 | 7 | 3.8 | 2 | >0.999 | |

| X-ray | 6.5 | 13 | 6.8 | 10 | 5.8 | 3 | >0.999 | |

| There is no test to screen for CC | 1.0 | 2 | 1.4 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 | … | |

| Do not know | 20.1 | 40 | 15.0 | 22 | 34.6 | 18 | 0.002 | |

| How can cervical cancer be prevented? | HPV vaccination * | 46.7 | 93 | 49.0 | 72 | 40.4 | 21 | 0.286 |

| Abstinence | 16.1 | 32 | 17.0 | 25 | 13.5 | 7 | 0.550 | |

| Healthy diet | 10.6 | 21 | 10.7 | 16 | 9.6 | 5 | 0.798 | |

| Exercise | 1.5 | 3 | 1.4 | 2 | 1.9 | 1 | >0.999 | |

| Screening using Pap smear * | 13.1 | 26 | 17.0 | 25 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.004 | |

| Don’t know | 24.6 | 49 | 21.1 | 31 | 34.6 | 18 | 0.052 | |

| Cervical cancer cannot be prevented | True | 34.2 | 68 | 33.3 | 49 | 36.5 | 19 | 0.675 |

| False * | 64.3 | 128 | 64.6 | 95 | 63.5 | 33 | 0.880 | |

| Don’t know | 1.5 | 3 | 2.0 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 | … | |

| Screening can detect cervical lesions so they do not develop into cancer | True * | 79.9 | 159 | 81.0 | 119 | 76.9 | 40 | 0.533 |

| False | 191 | 38 | 17.7 | 26 | 23.1 | 12 | 0.395 | |

| Don’t know | 1.0 | 2 | 1.4 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 | … | |

| HPV vaccine can prevent cervical cancer | True * | 76.4 | 152 | 76.2 | 112 | 76.9 | 40 | 0.915 |

| False | 21.6 | 43 | 21.1 | 31 | 23.1 | 12 | 0.847 | |

| Don’t know | 2.0 | 4 | 2.7 | 4 | 0.0 | 0 | … | |

| The use of condoms can help prevent HPV infection | True * | 85.4 | 170 | 85.7 | 126 | 84.6 | 44 | 0.847 |

| False | 13.1 | 26 | 12.2 | 18 | 15.4 | 8 | 0.564 | |

| Don’t know | 1.5 | 3 | 2.0 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 | … | |

| Is there a treatment for cervical cancer? | Yes * | 61.3 | 122 | 63.3 | 93 | 55.8 | 29 | 0.340 |

| No | 11.6 | 23 | 10.2 | 15 | 9.6 | 5 | 0.903 | |

| Maybe | 10.6 | 21 | 8.8 | 13 | 15.4 | 8 | 0.187 | |

| Do not know | 16.6 | 33 | 17.7 | 26 | 13.5 | 7 | 0.481 | |

| Screened Women, N = 68 | Unscreened Women, N = 79 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | p-Value | |

| HPV causes cervical cancer. | 58.8 | 40 | 32.9 | 26 | 0.003 |

| Early stages of cervical cancer do not have signs/symptoms. | 35.3 | 24 | 21.5 | 17 | 0.068 |

| HPV infection increases the risk of cervical cancer. | 63.2 | 43 | 39.2 | 31 | 0.005 |

| Smoking increases the risk of cervical cancer. | 22.1 | 15 | 27.8 | 22 | 0.451 |

| HIV and other STIs increases cervical cancer risk. | 35.3 | 24 | 32.9 | 26 | 0.862 |

| Early sexual debut increases the risk of cervical cancer. | 16.2 | 11 | 32.9 | 26 | 0.023 |

| HPV infection is common. | 51.5 | 35 | 41.8 | 33 | 0.251 |

| HPV is sexually transmitted. | 72.1 | 49 | 59.5 | 47 | 0.121 |

| Having multiple sexual partners a risk factor for cervical cancer. | 79.4 | 54 | 70.9 | 56 | 0.258 |

| Pap smear is used for cervical cancer screening. | 79.4 | 54 | 40.5 | 32 | <0.001 |

| Cervical cancer can be prevented by screening using a Pap smear. | 16.2 | 11 | 12.7 | 10 | 0.639 |

| Cervical cancer can be prevented by HPV vaccination. | 55.9 | 38 | 44.3 | 35 | 0.187 |

| Cervical cancer can be prevented. | 72.1 | 49 | 58.2 | 46 | 0.087 |

| Screening can detect cervical lesions so they do not develop into cancer. | 83.8 | 57 | 78.5 | 62 | 0.528 |

| The HPV vaccine can prevent cervical cancer. | 77.9 | 53 | 74.7 | 59 | 0.700 |

| The use of condoms can help prevent HPV infection. | 89.7 | 61 | 82.3 | 65 | 0.242 |

| There is treatment for cervical cancer. | 60.3 | 41 | 65.8 | 52 | 0.498 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mbulawa, Z.Z.A.; Mahlangu, L.L.; Makhabane, E.; Mavivane, S.; Nongcula, S.; Phafa, A.; Sihlobo, A.; Zide, M.; Mkiva, A.; Ngobe, T.N.; et al. Poor Cervical Cancer Knowledge and Awareness among Women and Men in the Eastern Cape Province Rural Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206916

Mbulawa ZZA, Mahlangu LL, Makhabane E, Mavivane S, Nongcula S, Phafa A, Sihlobo A, Zide M, Mkiva A, Ngobe TN, et al. Poor Cervical Cancer Knowledge and Awareness among Women and Men in the Eastern Cape Province Rural Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(20):6916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206916

Chicago/Turabian StyleMbulawa, Zizipho Z. A., Lindelo L. Mahlangu, Esihle Makhabane, Sisanda Mavivane, Sindisiwe Nongcula, Anathi Phafa, Ayabonga Sihlobo, Mbalentle Zide, Athenkosi Mkiva, Thembeka N. Ngobe, and et al. 2023. "Poor Cervical Cancer Knowledge and Awareness among Women and Men in the Eastern Cape Province Rural Community" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 20: 6916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206916

APA StyleMbulawa, Z. Z. A., Mahlangu, L. L., Makhabane, E., Mavivane, S., Nongcula, S., Phafa, A., Sihlobo, A., Zide, M., Mkiva, A., Ngobe, T. N., Njenge, L., Kwake, P., & Businge, C. B. (2023). Poor Cervical Cancer Knowledge and Awareness among Women and Men in the Eastern Cape Province Rural Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(20), 6916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20206916