A Qualitative Evaluation of a Health Access Card for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in a City in Northern England

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

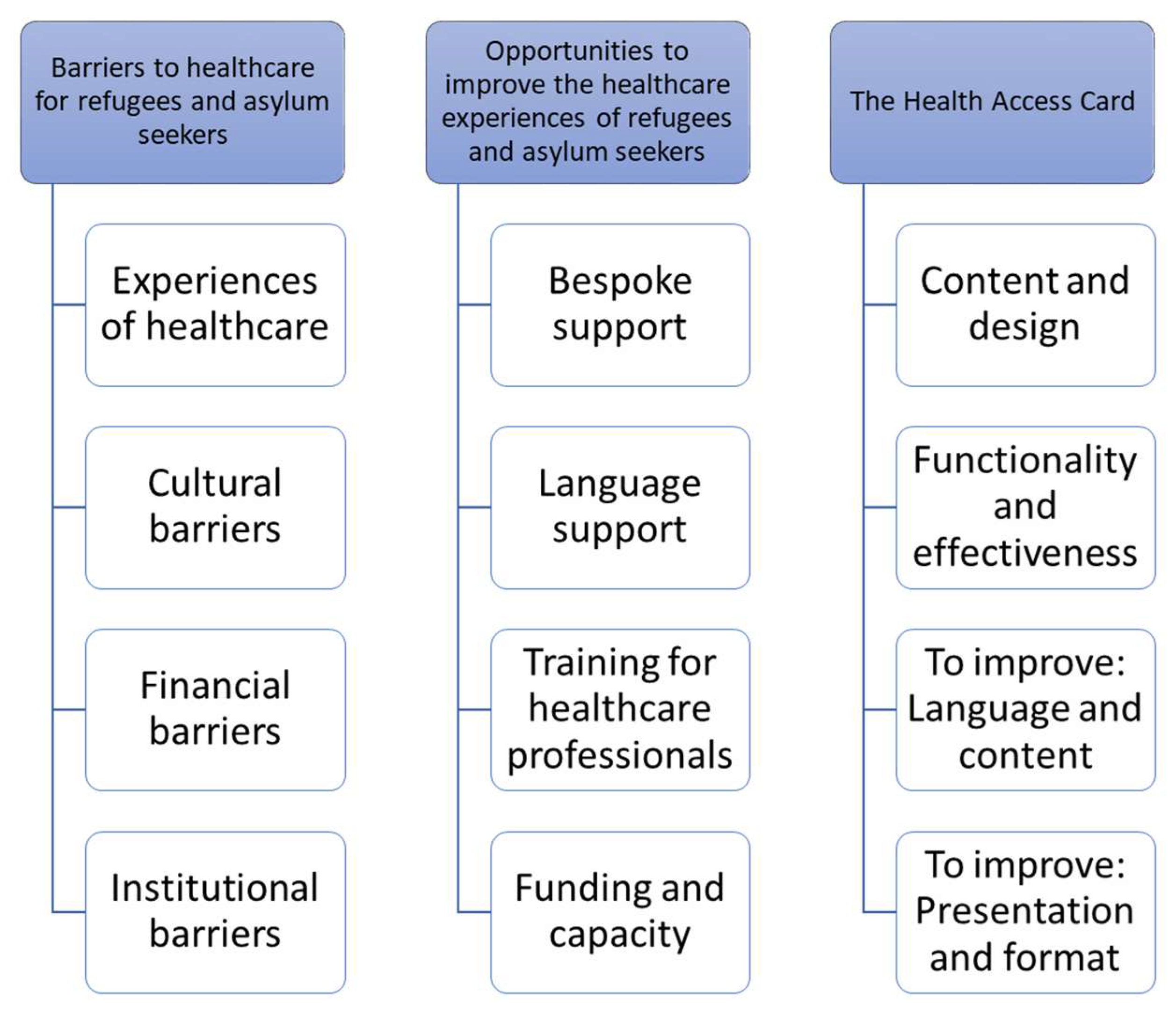

3. Results

4. Barriers to Healthcare for Refugees and Asylum Seekers

4.1. Experiences of Healthcare

“We’ve had a few clients who have moved from the East end of the city over to the West end, and they won’t change their GP because the GP they’ve got is great, they love their GP and they’re wonderful and they don’t want to change, so, and that GP has been quite happy to still have that person registered with them…”(P1)

“Health visitors and midwives are absolutely fantastic with this client group, yeah they really go above and beyond to try to help them as much as they can, so yeah I would say that’s been really good, and I’ve done lots of joint working with midwives and health visitors…”(P7)

“The [support organisation], that’s for LBGT support for refugees and asylum seekers, I think, yeah it is it’s on the bottom of the card, I suppose it’s not physical health but more mental health support but they’ve been really good to work with, both for the [clients] and we’ve found them really helpful as well…”(P3)

“At the start I was confused, but once I got used to the system it seems alright… first time when I went to the emergency for example… I used to wait really long time [and would think] oh my goodness what’s that, but then I realised how the system works, how the patients are looked after… but yeah, it was alright…”(SU2)

“[The client] tried to ring up to get another prescription for, I think it was sleeping pills to help her because she struggles with anxiety and they said they can’t, they can’t have a meeting with her, the GP can’t see her because they’re not doing face to face [due to COVID-19 restrictions] and they don’t have someone to be an interpreter so she’ll just have to wait until after this.”(P3)

“I’ve got this client whose daughter is having quite severe psychotic episodes, she was admitted to hospital, she was, I don’t know if it’s like a young person’s mental health team or something, she was under their care for a few weeks, and now nothing’s happened, they haven’t kind of followed up with anything, and she’s had another quite serious episode in school where she was quite dangerous to other people, and I think she’s just been, well I think they feel like she’s been left…”(P7)

“They feel like that because they don’t understand, so they think because they are aliens [healthcare professionals] are reacting to them like that… “they don’t help us because we are foreigners””(SU1)

“It’s always been dental care that they’ve had most problems with, so a lot of the dentists that they go to register with tell them that they’ve got to pay, even if they’ve got an HC2, I think for some of the dental practices maybe there’s a misunderstanding with some of them…”(P1)

“That lady I mentioned before who had the miscarriage, she was destitute at the time that happened and she got charged for the work they did when she had to be taken in for the miscarriage, and the letters are quite brutal in that they say that if you don’t pay this within three months we will inform the Home Office and it will affect your claim, so people really panic and she found that really upsetting, having just gone through what she went through, and I went through Doctors of the World and they said yes the charges would stand currently.”(P1)

4.2. Cultural Barriers

“We’ve had one learner who’s sent me pictures of a letter from a consultant at a hospital to his GP, which he’s been copied into, and it’s all in English, he doesn’t speak any English, so he hasn’t received any kind of translated version of it, and it’s talking, I mean I know those letters do talk in third person, I saw so-and-so, but it’s really important the stuff that it’s talking about, and describing that there was a communication barrier and that she’s booked him in for a MRI scan anyway but she doesn’t know how much he understands…”(P3)

“I’m the only one who’s accessed those services [counselling], because my family doesn’t believe in mental health that much, like now they do but back then they didn’t…”(SU3)

“A lot of people come from cultures where mental health wouldn’t be something that was even recognised as an issue, so being able to describe that in the first place [is a barrier]…”(P4)

“Another barrier is the assumption that people leaving their home and living here are used to the system, they assume that it’s the same everywhere but it isn’t, they’d be really frustrated if they went to my country for example and tried to access, which is not stressful for me as I understand it…”(SU2)

4.3. Financial Barriers

“A lot of [clients] are saying “oh well we walked for two hours to get here, if we’d paid for the bus we wouldn’t have enough food for the day” so I think in terms of weighing up often it would be prioritising is it important enough to go to the doctors, more important than buying food for the week…”(P3)

4.4. Institutional Barriers

“I’ve worked with lots of people over the years who’ve kind of been in and out of various medical appointments talking about physical symptoms when actually it’s turned out, you know talking about headaches talking about stomach aches talking about different things, and again some if that is their way of describing it with the language and the cultural barriers, and some of that is I think the practitioners’ awareness of the particular needs of this population and that actually, you know, lots of people have experienced trauma and persecution and different things and actually for you to be aware of that, if people are coming in with headaches or different things, just explore some of that stuff…”(P4)

5. Opportunities to Improve the Healthcare Experiences of Refugees and Asylum Seekers

5.1. Bespoke Support

“Actually the most useful part was when a visitor came to my home and he actually took me and my husband to the places and he was speaking English but he tried to show how the places looked like, I didn’t understand everything he said but it gave me the idea how to get used to the system, so he actually took us to the places and, yeah, tried really hard to explain…”(SU2)

“I think like there’s more work to be done around people’s mental health, really. Like a lot more work. It’s such a huge area for our clients and for a lot of people, it’s a really difficult thing to manage and to deal with and talk about.”(P2)

5.2. Language Support

“it’s [the client’s] right to be able to understand that information, so just having translated documents, and then people who understand the barriers that people might be experiencing when they’re trying to access a service, would be really useful…”(P3)

5.3. Training for Healthcare Professionals

“I think it’s always a training issue. The more the surgery buys into training staff appropriately, the more awareness of someone’s situation and know what to pick up on, the work that these surgeries have been doing is great, because you know there’s a commitment there isn’t there and their staff are going to have that level of training and you know they’re kind of signed up to being welcoming to people and so, the more of that stuff that gets done the better, really.”(P2)

5.4. Funding and Capacity

“Because of various factors in Newcastle including years of you know austerity and funding cuts that have meant that lots of services that were previously there for asylum seekers and refugees are kind of contracted because of that, they [the voluntary sector] have been picking up asylum seekers much earlier in their journey so they’ve been picking up people who are just arriving in Newcastle, they’ve been picking up people who have been here and they haven’t had their decisions yet and actually they’ve got lots of work around integration at those earliest levels around school access and health access and different things…”(P4)

6. The Health Access Card

6.1. Content and Design

“Having that information on there that we can like point to, and make sure that people are informed and know how to use the kind of UK system of healthcare is really useful as well…”(P3)

“I think the information about the services is crucial, what service is provided at what time, and how, is important…”(SU3)

“I think what I’d like to see in there is something about midwives and health visitors as well, because clients don’t always realise that when you’re pregnant it’s a midwife you would see most rather than your GP, so I think that section could be improved…”(P1)

“It gives, like, images in its own self telling people that this is the thing you need to read if you’re looking for an optician or a dentist because there’s a picture of the glasses or a tooth, or the mother with the baby for pregnancy… so I think it’s easier in a graphical way…”(SU3)

“There is a lot of information on there now, obviously it’s quite dense, there is a lot of writing on there, so anybody, even if they do speak reasonably good English anybody where English isn’t a first language, it’s probably going to be quite daunting.”(P5)

“It doesn’t really look like something important, so… when you make something small, it doesn’t look big, the best way to say it… they don’t make [you] take it serious[ly]…”(SU1)

6.2. Functionality and Distribution

“Clients in [name of charity], yes, some of them ask us how can I access this kind of healthcare, so I just gave it to them and, you know, point them to try this…”(SU1)

“Frankly, when I came into the country, I wanted something like this, the only thing was there was nothing at that time… now I know these places where I have to go.”(SU3)

“Most of the time when I’ve used it it’s been the first time that someone has seen it, I’ve never given it out and someone’s already had one or known about it.”(P3)

6.3. To Improve: Language and Content

“Another thing is, yeah, the best option would be if it is translated into as many languages as possible…”(SU2)

“I don’t know what a GP is for example, I would add an explanation of this abbreviation… it’s still complicated, it’s still really hard for me, everywhere abbreviations are used and it assumes that you know about it…”(SU2)

“Maybe if there were specific projects that were aimed at refugees they might be more accessible than just the general link to the website.”(P3)

“Something about certain organisations that are working with people from a similar [refugee and asylum] background… so that they can tell them about the Health Access Card more properly, so that they can take them to the GP services because I know they have, like, health care champions…”(SU3)

“In our countries doctors do not work like this so we just go to doctor and you can meet them right away, it’s like a drop-in, you just go there and it’s not ten minutes, so you can share whatever the problem is for as long as you want, but there are some different systems and they are expecting that to happen here but I’ve seen a lot of people, you know, complaining about how doctors are working.”(SU1)

6.4. To Improve: Presentation and Format

“I think we need to make more use of images in explaining something, because images, you know, they’re international, and there’s a lot more graphic designers out there who can do, who can explain something graphically with a picture that people get the concept of…”(P1)

“I would like a bit more pictures, something more visual, rather than lots of writing I would add a bit more of this kind of pictures… maybe I would add a bit, for example a tiny map, for example there is not many A&E department in Newcastle…”(SU2)

“Maybe consider having an expanded version of the cards available online, so you could have less text on the actual card. You could say, actually you can find more information on this website…”(P5)

“The majority of patients, do have [internet] access, but you, of course, there are patients that don’t either have devices or don’t have data or Wi-Fi, so whenever you are providing service online you do have make sure that is also available in other formats as well.”(P5)

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Available online: www.unhcr.org/uk/figures-at-a-glance.html (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- UNHCR. Available online: www.unhcr.org/refugees.html (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- UNHCR. Available online: www.unhcr.org/asylum-seekers.html (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Home Office (UK Government). Available online: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-statistics-year-ending-december-2021/how-many-people-do-we-grant-asylum-or-protection-to#data-tables (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Luiking, M.L.; Heckemann, B.; Ali, P.; Dekker-van Doorn, C.; Ghosh, S.; Kydd, A.; Watson, R.; Patel, H. Migrants’ Healthcare Experience: A Meta-Ethnography Review of the Literature. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2019, 51, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR. The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/uk/about-us/background/4ec262df9/1951-convention-relating-status-refugees-its-1967-protocol.html (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- IOM (International Organization for Migration). Migration Governance Indicators: A Global Perspective. 2019. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-governance-indicators-global-perspective (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- United Nations Foundation. Available online: https://unfoundation.org/what-we-do/issues/sustainable-development-goals/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA4aacBhCUARIsAI55maGlLKpdsKowwJEfZs0QO2FzDyPXi-QP-K2Rw-XfwGNb9he9wQO-jl8aAgynEALw_wcB (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- UNHCR. Global Compact on Refugees. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/5c658aed4 (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- OHID (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, UK Government). Available online: www.gov.uk/guidance/nhs-entitlements-migrant-health-guide (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Khanom, A.; Alanazy, W.; Couzens, L.; Evans, B.A.; Fagan, L.; Fogarty, R.; John, A.; Khan, T.; Kingston, M.R.; Moyo, S.; et al. Asylum seekers’ and refugees’ experiences of accessing health care: A qualitative study. BJGP Open 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.; Tomkow, L.; Farrington, R. Access to primary health care for asylum seekers and refugees: A qualitative study of service user experiences in the UK. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019, 69, e537–e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, T.; Howard, N. Mental healthcare for asylum-seekers and refugees residing in the United Kingdom: A scoping review of policies, barriers, and enablers. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2021, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKnight, P.; Goodwin, L.; Kenyon, S. A systematic review of asylum-seeking women’s views and experiences of UK maternity care. Midwifery 2019, 77, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, T.J.; Browne, A.; Haworth, S.; Wurie, F.; Campos-Matos, I. Service Evaluation of the English Refugee Health Information System: Considerations and Recommendations for Effective Resettlement. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, E. Safe surgeries: How Doctors of the World are helping migrants access healthcare. BMJ 2019, 364, l88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PIqbal, M.; Walpola, R.; Harris-Roxas, B.; Li, J.; Mears, S.; Hall, J.; Harrison, R. Improving primary health care quality for refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review of interventional approaches. Health Expect 2022, 25, 2065–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, G.; Blumell, L.; Bunce, M. Beyond the ‘refugee crisis’: How the UK news media represent asylum seekers across national boundaries. Int. Comm. Gaz. 2021, 83, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flug, M.; Hussein, J. Integration in the Shadow of Austerity—Refugees in Newcastle upon Tyne. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, P. The mental health needs of adult asylum seekers in Newcastle upon Tyne. J. Public Ment. Health 2005, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroppo, E.; Muscelli, C.; Brogna, P.; Paci, M.; Camerino, C.; Bria, P. Relating with migrants: Ethnopsychiatry and psychotherapy. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2009, 45, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pottie, K.; Ratnayake, A.; Ahmed, R.; Veronis, L.; Alghazali, I. How refugee youth use social media: What does this mean for improving their health and welfare? J. Public Health Pol. 2020, 41, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Lindenmeyer, A.; Phillimore, J.; Lessard-Phillips, L. Vulnerable migrants’ access to healthcare in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Public Health 2022, 203, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guma, T.; Blake, Y.; Maclean, G.; Sharapov, K. Safe Environment? Understanding the Housing of Asylum Seekers and Refugees during the COVID-19 Outbreak; Final Report; Edinburgh Napier University: Edinburgh, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bamford, J.; Fletcher, M.; Leavey, G. Mental Health Outcomes of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors: A Rapid Review of Recent Research. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study ID | Role | Age | Gender | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (professional) 1 | Third sector support worker | - | Female | White British |

| P2 | Third sector support worker | - | Female | White British |

| P3 | Third sector support worker | - | Female | White British |

| P4 | Local authority support worker | - | Female | White British |

| P5 | GP | - | Male | White British |

| P6 | Third sector support officer | - | Male | White British |

| P7 | Third sector organisation trustee | - | Female | Middle Eastern |

| P8 | Local authority support worker | - | Female | White British |

| SU (service user) 1 | Service user (refugee status) | Late 20s | Male | Pakistani |

| SU2 | Service user (refugee status) | Mid 30s | Female | Eastern European |

| SU3 | Service user (refugee status) | Late teens | Female | Indian |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moffat, M.; Nicholson, S.; Darke, J.; Brown, M.; Minto, S.; Sowden, S.; Rankin, J. A Qualitative Evaluation of a Health Access Card for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in a City in Northern England. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021429

Moffat M, Nicholson S, Darke J, Brown M, Minto S, Sowden S, Rankin J. A Qualitative Evaluation of a Health Access Card for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in a City in Northern England. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021429

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoffat, Malcolm, Suzanne Nicholson, Joanne Darke, Melissa Brown, Stephen Minto, Sarah Sowden, and Judith Rankin. 2023. "A Qualitative Evaluation of a Health Access Card for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in a City in Northern England" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021429

APA StyleMoffat, M., Nicholson, S., Darke, J., Brown, M., Minto, S., Sowden, S., & Rankin, J. (2023). A Qualitative Evaluation of a Health Access Card for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in a City in Northern England. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021429