Linking Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression to Mindfulness: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Concept and Measurement of Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression

1.2. Concept and Measurement of Mindfulness

1.3. The Relationship between Mindfulness and Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression

1.4. Possible Moderating Variable

1.5. Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

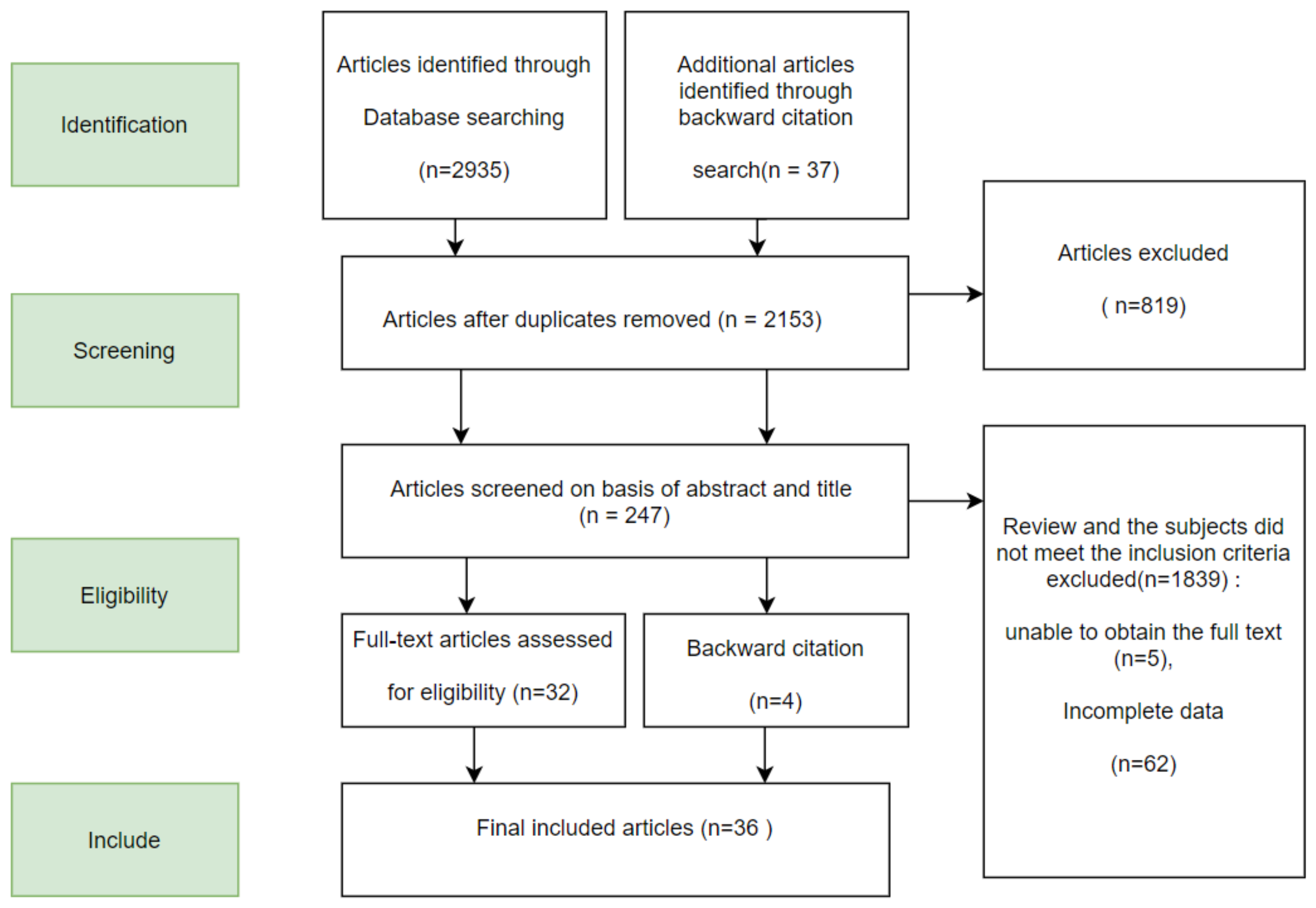

2.1. Literature Search and Screening

2.2. Coding Process

2.3. Quality Rating

2.4. Analysis Process

3. Results

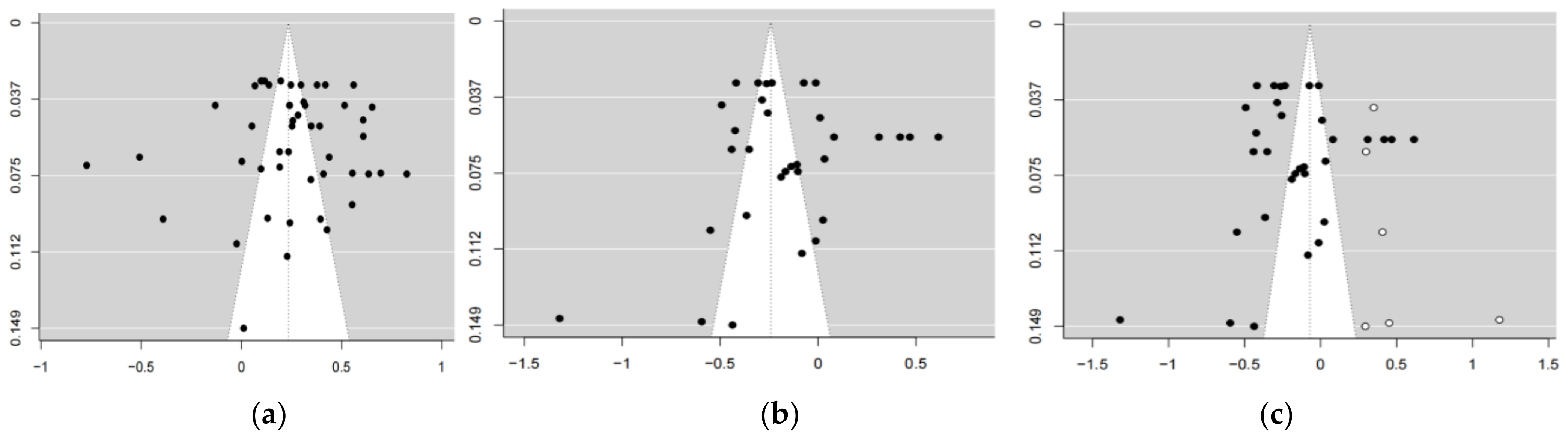

3.1. Publication Bias Test

3.2. Model Comparison

3.3. Pooled Effects

3.4. Analysis of Moderating Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. The Moderate Effect of Gender and Mindfulness Measurement Tools

4.2. Research Deficiencies and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID1 | ID2 | Author (First) | py | n | α1 | α2 | CB | Age | Gender | MI | ERI | MD | ERD | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Zhang | 2021 | 222 | east | 21.55 | 0.55 | MAAS | ERQ | M | R | 0.002 | ||

| 1 | 2 | Zhang | 2021 | 222 | east | 21.55 | 0.55 | MAAS | ERQ | M | S | 0.027 | ||

| 2 | 3 | Liu | 2015 | 448 | 0.73 | 0.81 | east | 21.15 | 0.45 | FFMQ | ERS | M | R | 0.417 |

| 2 | 4 | Liu | 2015 | 448 | 0.73 | 0.73 | east | 21.15 | 0.45 | FFMQ | ERS | M | S | 0.007 |

| 3 | 5 | Li | 2015 | 397 | 0.8 | 0.881 | east | 0.77 | FFMQ | CERQ | M | R | 0.281 | |

| 3 | 6 | Li | 2015 | 397 | 0.8 | 0.881 | east | 0.77 | FFMQ | CERQ | M | R | 0.208 | |

| 3 | 7 | Li | 2015 | 397 | 0.8 | 0.881 | east | 0.77 | FFMQ | CERQ | M | R | 0.312 | |

| 3 | 8 | Li | 2015 | 397 | 0.8 | 0.881 | east | 0.77 | FFMQ | CERQ | M | R | 0.044 | |

| 4 | 9 | Laura | 2019 | 256 | 0.92 | 0.813 | west | 18.95 | 0.32 | CEDMI | ERQ | NJ | R | 0.20 |

| 4 | 10 | Laura | 2019 | 256 | 0.92 | 0.774 | west | 18.95 | 0.32 | CEDMI | ERQ | NJ | S | −0.35 |

| 4 | 11 | McKee | 2019 | 256 | 0.89 | 0.813 | west | 18.95 | 0.32 | CEDMI | ERQ | AC | R | 0.16 |

| 4 | 12 | McKee | 2019 | 256 | 0.89 | 0.774 | west | 18.95 | 0.32 | CEDMI | ERQ | AC | S | −0.28 |

| 5 | 13 | Hui | 2019 | 594 | 0.83 | 0.71 | east | 1.14 | MAAS | ERS | M | R | 0.44 | |

| 5 | 14 | Hui | 2019 | 594 | 0.83 | 0.67 | east | 1.14 | MAAS | ERS | M | S | −0.34 | |

| 6 | 15 | Amundsen | 2020 | 108 | 0.87 | 0.83 | west | CAMM | ERQ-CA | M | R | 0.202 | ||

| 6 | 16 | Amundsen | 2020 | 108 | 0.87 | 0.75 | west | CAMM | ERQ-CA | M | S | 0.02 | ||

| 7 | 17 | Prakash | 2015 | 48 | 0.90 | west | 65.13 | 0.538 | MAAS | other | M | R | 0.01 | |

| 8 | 18 | Prakash | 2015 | 48 | 0.75 | west | 23.61 | 0.58 | MAAS | other | M | S | −0.42 | |

| 9 | 19 | Malikin | 2020 | 205 | 0.91 | 0.89 | west | 0.48 | MAAS | ERQ | M | R | 0.17 | |

| 9 | 20 | Malikin | 2020 | 205 | 0.91 | 0.76 | west | MAAS | ERQ | M | S | −0.09 | ||

| 10 | 21 | Desrosiers | 2013 | 187 | 0.89 | 0.91 | west | 38 | 0.56 | FFMQ | ERQ | M | R | 0.61 |

| 11 | 22 | Kerin | 2017 | 312 | 0.82 | 0.9 | west | 22 | 0.47 | FFMQ | other | NJ | S | 0.47 |

| 11 | 23 | Kerin | 2017 | 312 | 0.84 | 0.9 | west | 22 | 0.47 | FFMQ | other | NJ | S | 0.38 |

| 11 | 24 | Kerin | 2017 | 312 | 0.83 | 0.9 | west | 22 | 0.47 | FFMQ | O | O | S | 0.07 |

| 11 | 25 | Kerin | 2017 | 312 | 0.82 | 0.9 | west | 22 | 0.47 | FFMQ | other | AW | S | 0.34 |

| 11 | 26 | Kerin | 2017 | 312 | 0.83 | 0.9 | west | 22 | 0.47 | FFMQ | other | D | S | 0.26 |

| 12 | 27 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.93 | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | NJ | R | 0.12 | ||

| 12 | 28 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.93 | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | NJ | S | −0.26 | ||

| 12 | 29 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.83 | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | NR | R | 0.42 | ||

| 12 | 30 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.83 | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | NR | S | −0.01 | ||

| 12 | 31 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.84 | west | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | O | R | 0.3 | |

| 12 | 32 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.84 | 0.8 | west | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | O | S | −0.06 |

| 12 | 33 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.91 | west | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | AW | R | 0.21 | |

| 12 | 34 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.91 | west | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | AW | S | −0.2 | |

| 12 | 35 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.91 | west | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | D | R | 0.25 | |

| 12 | 36 | Warner | 2020 | 1094 | 0.91 | 0.91 | west | 34.43 | 0.72 | FFMQ | ERQ | D | S | −0.36 |

| 13 | 37 | Brockman | 2016 | 187 | 0.85 | 0.79 | west | 23.9 | 0.3 | LMS | ERQ | M | R | 0.46 |

| 13 | 38 | Brockman | 2016 | 187 | 0.85 | 0.73 | west | 23.9 | 0.3 | LMS | ERQ | M | S | −0.13 |

| 14 | 39 | Pepping | 2016 | 113 | 0.85 | 0.84 | west | 14.9 | 0.79 | CAMM | ERQ-CA | M | R | 0.11 |

| 14 | 40 | Pepping | 2016 | 113 | 0.85 | 0.65 | west | 14.9 | 0.79 | CAMM | ERQ-CA | M | S | −0.26 |

| 15 | 41 | LockerJr | 2016 | 80 | 0.87 | 0.82 | east | MAAS | ERQ | M | S | −0.07 | ||

| 15 | 42 | LockerJr | 2016 | 80 | 0.87 | 0.82 | est | MAAS | ERQ | M | R | 0.19 | ||

| 16 | 43 | Ma | 2019 | 1067 | 0.78 | 0.63 | east | 14.84 | 0.73 | MAAS | ERQ | M | S | −0.18 |

| 16 | 44 | Ma | 2019 | 1067 | 0.78 | 0.7 | est | 14.84 | 0.73 | MAAS | ERQ | M | R | 0.05 |

| 17 | 45 | Malik | 2021 | 210 | 0.89 | 0.9 | est | 21 | 0.98 | FFMQ | CERQ | M | R | −0.58 |

| 18 | 46 | Gregório | 2013 | 350 | 0.9 | 0.9 | west | 29.85 | 0.2 | MAAS | WBSI | M | S | −0.36 |

| 19 | 47 | Hayes-Skelton | 2013 | 1097 | 0.86 | 0.76 | west | 26.58 | 0.36 | FFMQ | ERQ | M | R | 0.32 |

| 20 | 48 | Cindy | 2013 | 89 | 0.87 | 0.74 | west | 64.13 | 0.44 | MAAS | ERQ | M | S | −0.01 |

| 20 | 49 | Cindy | 2013 | 89 | 0.87 | 0.83 | west | 64.13 | 0.44 | MAAS | ERQ | M | R | −0.02 |

| 21 | 50 | Hawkes | 2019 | 496 | west | 31.4 | 0.21 | MAAS | ERQ | M | S | −0.21 | ||

| 21 | 51 | Hawkes | 2019 | 496 | west | 31.4 | 0.21 | MAAS | ERQ | M | R | 0.23 | ||

| 22 | 52 | Prakash | 2015 | 48 | 0.76 | 0.9 | west | 65.4 | 0.55 | MAAS | WBSI | M | S | −0.34 |

| 23 | 53 | Prakash | 2015 | 50 | 0.9 | 0.9 | west | 23.6 | 0.56 | MAAS | WBSI | M | S | −0.78 |

| 24 | 54 | Stevenson | 2018 | 174 | 0.85 | 0.66 | west | 21.18 | 0.35 | FFMQ | ERQ | M | S | −0.14 |

| 24 | 55 | Stevenson | 2018 | 174 | 0.85 | 0.89 | west | 21.18 | 0.35 | FFMQ | ERQ | M | R | 0.29 |

| 25 | 56 | Ángel Cano | 2020 | 200 | 0.92 | 0.84 | west | 21.3 | 0.96 | MAAS | ERQ | M | S | −0.12 |

| 25 | 57 | Ángel Cano | 2020 | 200 | 0.92 | 0.92 | west | 21.3 | 0.96 | MAAS | ERQ | M | R | 0.09 |

| 26 | 58 | Chen | 2021 | 187 | 0.82 | 0.73 | east | 21.6 | 0.11 | CAMS-R | ERQ | M | S | −0.08 |

| 26 | 59 | Chen | 2021 | 187 | 0.82 | 0.83 | east | 21.6 | 0.11 | CAMS-R | ERQ | M | R | 0.32 |

| 27 | 60 | James | 2017 | 98 | 0.8 | 0.88 | west | 37.55 | 1.17 | MAAS | WBSI | M | S | −0.42 |

| 28 | 61 | Desrosiers | 2014 | 189 | 0.76 | 0.91 | west | 38 | 0.55 | FFMQ | ERQ | M | R | 0.50 |

| 28 | 62 | Desrosiers | 2014 | 189 | 0.84 | 0.91 | west | 38 | 0.55 | FFMQ | ERQ | O | R | 0.44 |

| 29 | 63 | Hanley | 2014 | 329 | 0.73 | 0.9 | 35 | 0.45 | FFMQ | CERQ | M | R | 0.44 | |

| 30 | 64 | Hanley | 2014 | 130 | 0.74 | 0.9 | 38 | 0.34 | FFMQ | CERQ | M | R | 0.41 | |

| 31 | 65 | Hanley | 2014 | 101 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 22 | 0.36 | FFMQ | CERQ | M | R | 0.34 | |

| 32 | 66 | Kaynak | 2021 | 620 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 21.88 | 0.45 | FFMQ | ERQ | NJ | R | −0.11 | |

| 32 | 67 | Kaynak | 2021 | 620 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 21.88 | 0.45 | FFMQ | ERQ | NR | R | 0.4 | |

| 32 | 68 | Kaynak | 2021 | 620 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 21.88 | 0.45 | FFMQ | ERQ | O | R | 0.2 | |

| 32 | 69 | Kaynak | 2021 | 620 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 21.88 | 0.45 | FFMQ | ERQ | AW | R | 0.2 | |

| 32 | 70 | Kaynak | 2021 | 620 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 21.88 | 0.45 | FFMQ | ERQ | D | R | 0.26 | |

| 33 | 71 | Kaynak | 2021 | 210 | 0.89 | 0.9 | east | 21 | 0.98 | FFMQ | CERQ | M | R | −0.58 |

| 34 | 72 | Kaynak | 2022 | 1251 | 0.84 | 0.71 | east | MAAS | CERQ | M | R | 0.15 | ||

| 34 | 73 | Kaynak | 2022 | 1251 | 0.84 | 0.72 | east | MAAS | CERQ | M | R | 0.09 | ||

| 34 | 74 | Kaynak | 2022 | 1251 | 0.86 | 0.71 | east | MAAS | CERQ | M | R | 0.08 | ||

| 34 | 75 | Kaynak | 2022 | 1251 | 0.86 | 0.78 | east | MAAS | CERQ | M | R | 0.08 | ||

| 35 | 76 | Kaynak | 2018 | 236 | 0.88 | 0.82 | west | 23.83 | 0.39 | MAAS | AVEM | M | R | 0.35 |

| 36 | 77 | Kaynak | 2018 | 112 | 0.87 | 0.89 | west | 27.35 | 0.4 | MAAS | AVEM | M | R | 0.33 |

| 37 | 78 | Kaynak | 2018 | 236 | 0.88 | 0.83 | west | 23.83 | 0.39 | MAAS | AVEM | M | R | −0.4 |

| 38 | 79 | Kaynak | 2018 | 112 | 0.87 | 0.85 | west | 27.35 | 0.4 | MAAS | AVEM | M | R | −0.32 |

| 39 | 80 | Kaynak | 2020 | 442 | 0.84 | 0.83 | east | 20.29 | 0.842 | MAAS | ERQ | M | R | 0.21 |

| 40 | 81 | Kaynak | 2021 | 672 | 0.79 | 0.79 | east | 1.18 | MAAS | ERS | M | S | −0.22 | |

| 40 | 82 | Kaynak | 2021 | 672 | 0.79 | 0.85 | east | 1.18 | MAAS | ERS | M | R | 0.247 |

References

- Rottenberg, J.; Gross, J.J.; Gotlib, I.H. Emotion context insensitivity in major depressive disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2005, 114, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackett, M.A.; Salovey, P. Measuring emotional intelligence as a mental ability with the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. In Measurement of Emotional Intelligence; Geher, G., Ed.; American Psychological Association: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- John, O.O.; Gross, J.J. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality. processes, individual differences, and life span development. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katana, M.; Röcke, C.; Spain, S.M.; Allemand, M. Emotion Regulation, Subjective Well–Being, and Perceived Stress in Daily Life of Geriatric Nurses. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, T.; Carr, D.C.; Hajcak, G.; Sheffler, J.; Sachs–Ericsson, N. Cognitive reappraisal, emotional suppression, and depressive and anxiety symptoms in later life: The moderating role of gender. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 2390–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hon, T.; Das, R.K.; Kamboj, S.K. The effects of cognitive reappraisal following retrieval–procedures designed to destabilize alcohol memories in high–risk drinkers. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozovich, F.A.; Goldin, P.; Lee, I.; Jazaieri, H.; Heimberg, R.G.; Gross, J.J. The effect of rumination and reappraisal on social anxiety symptoms during cognitive–behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 71, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skymba, H.V.; Troop–Gordon, W.; Modi, H.H.; Davis, M.M.; Weldon, A.L.; Xia, Y.; Heller, W.; Rudolph, K.D. Emotion mindsets and depressive symptoms in adolescence: The role of emotion regulation competence. Emotion 2022, 22, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucito, L.M.; Juliano, L.M.; Toll, B.A. Cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression emotion regulation strategies in cigarette smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egloff, B.; Schmukle, S.C.; Burns, L.R.; Schwerdtfeger, A. Spontaneous emotion regulation during evaluated speaking tasks: Associations with negative affect, anxiety expression, memory, and physiological responding. Emotion 2006, 6, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, B.; Sharma, M.; Rush, S.E.; Fournier, C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, W.; Preece, D.A.; Xu, D.; Li, H.; Liu, N.; Fu, G.; Wang, Y.; Qian, Q.; Gross, J.J.; et al. Emotion dysregulation in adults with ADHD: The role of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 319, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalot, F.; Delplanque, S.; Sander, D. Mindful regulation of positive emotions: A comparison with reappraisal and expressive suppression. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhofer, T.; Reess, T.J.; Fissler, M.; Winnebeck, E.; Grimm, S.; Gärtner, M.; Fan, Y.; Huntenburg, J.M.; Schroeter, T.A.; Gummersbach, M.; et al. Effects of mindfulness training on emotion regulation in patients with depression: Reduced dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation indexes early beneficial changes. Psychosom. Med. 2021, 83, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guendelman, S.; Medeiros, S.; Rampes, H. Mindfulness and emotion regulation: Insights from neurobiological, psychological, and clinical studies. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Gullone, E.; Allen, N.B. Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naragon–Gainey, K.; McMahon, T.P.; Chacko, T.P. The structure of common emotion regulation strategies: A meta–analytic examination. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 384–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.S.; Arnkoff, D.B.; Glass, C.R. The neuroscience of mindfulness: How mindfulness alters the brain and facilitates emotion regulation. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1471–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iani, L.; Lauriola, M.; Chiesa, A.; Cafaro, V. Associations between mindfulness and emotion Regulation: The key role of describing and nonreactivity. Mindfulness 2018, 10, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, S.L.; Robins, C.J.; Smoski, M.J.; Dagenbach, J.; Leary, M.R. Reappraisal and mindfulness: A comparison of subjective effects and cognitive costs. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Chang, L.; Chen, L.; Fei, J.; Zhou, R. Exploring the roles of dispositional mindfulness and cognitive reappraisal in the relationship between neuroticism and depression among postgraduate students in China. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1605074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberth, J.; Sedlmeier, P. The effects of mindfulness meditation: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2012, 3, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Using self–report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphiphatthana, B.; Jose, P.E. The relationship between dispositional mindfulness and grit moderated by meditation experience and culture. Mindfulness 2019, 11, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss, I.B.; Cook, C.L.; Gross, J.J. Automatic emotion regulation during anger provocation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The extended process model of emotion regulation: Elaborations, applications, and future directions. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, J.A.J.; Julian, K.; Rosenfield, D.; Powers, M.B. Threat reappraisal as a mediator of symptom change in cognitive–behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders: A systematic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 80, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, P.R.; Mcrae, K.; Ramel, W.; Gross, J.J. The neural bases of emotion regulation: Reappraisal and suppression of negative emotion. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 63, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.D.; Wilhelm, F.H.; Gross, J.J. All in the mind’s eye? Anger rumination and reappraisal. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well–being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, K.; Ochsner, K.N.; Mauss, I.B.; Gabrieli, J.J.D.; Gross, J.J. Gender differences in emotion regulation: An fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2008, 11, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, M.; Orrù, G.; Gemignani, A.; Ciacchini, R.; Miniati, M.; Conversano, C. Mindfulness and Defense Mechanisms as Explicit and Implicit Emotion Regulation Strategies against Psychological Distress during Massive Catastrophic Events. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D.A.; Becerra, R.; Robinson, K.; Gross, J.J. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties in General Community Samples. J. Pers. Assess. 2020, 102, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wang, M.C.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, H.; Yang, W. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for children and adolescents (ERQ-CA): Factor structure and measurement invariance in a Chinese student samples. J. Pers. Assess. 2022, 104, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat–Zinn, J. Mindfulness–based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.A.; Stanton, S.J.; Greeson, J.M.; Smoski, M.J.; Wang, L. Psychological and neural mechanisms of trait mindfulness in reducing depression vulnerability. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat–Zinn, J. The liberative potential of mindfulness. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraines, M.A.; Kelberer, L.J.; Marks, C.P.K.; Wells, T.T. Trait mindfulness and attention to emotional information: An eye tracking study. Conscious. Cogn. 2021, 95, 103213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, J.A.; Fischer, R. The state of dispositional mindfulness research. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 1357–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness Interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2017, 68, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well–being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; ten Klooster, P.M.; Fledderus, M.; Veehof, M.; Baer, R. Psychometric properties of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in depressed adults and development of a short form. Assessment 2011, 18, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslin, F.C.; Zack, M.; McMain, S. An information-processing analysis of mindfulness: Implications for relapse prevention in the treatment of substance abuse. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 9, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, A.W.; Garland, E.L. Dispositional mindfulness co-varies with self-reported positive reappraisal. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014, 66, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luders, E.; Toga, A.W.; Lepore, N.; Gaser, C. The underlying anatomical correlates of long-term meditation: Larger hippocampal and frontal volumes of gray matter. Neuroimage 2009, 45, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, M.B.; Tramm, G.; O’Toole, M.S. Age-group differences in instructed emotion regulation effectiveness: A systematic review and meta–analysis. Psychol. Aging 2021, 36, 957–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L. Socioemotional selectivity theory: The role of perceived endings in human motivation. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 1181–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, T.; Knight, L.K.; Naaz, F.; Patton, S.C.; Depue, B.E. Gender differences in functional connectivity during emotion regulation. Neuropsychologia 2021, 156, 107829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, E.A.; Lee, T.L.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture–specific? Emotion 2007, 7, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, N.; Amjad, N. Cross cultural variation in emotion regulation: A systematic review. ANNALS 2017, 23, 77–90. Available online: http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7dba/0fab5eeee938cec3df4f12c099c8a94fca0f.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.W.; Jiang, G.R. Effectiveness of mindfulness meditation in intervention for anxiety: A meta–analysis. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2018, 50, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-García, L.; Takkouche, B.; Seoane, G.; Senra, C. Mediators linking insecure attachment to eating symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, M.W.; Wilson, D.B. Practical Meta–Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; Available online: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/ct2–library/90/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Assink, M.; Wibbelink, C.J. Fitting three–level meta–analytic models in R: A step–by–step tutorial. Quant. Meth. Psych. 2016, 12, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta–analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlke, J.A.; Wiernik, B.M. Psychmeta: Psychometric Meta–Analysis Toolkit (Version 0.1.0). 2018. Available online: https://cran.r–project.org/package=psychmeta (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta–analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ Br. Med. J. 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel–plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta–analysis. Biometrics 2015, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta–analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta–analysis. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. JASP, Version 0.16.3; JASP Team: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoš, F.; Maier, M.; Quintana, D.S.; Wagenmakers, E.J. Adjusting for publication bias in JASP and R: Selection models, PET-PEESE, and robust bayesian mmeta-analysis. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Furukawa, T.A.; Ebert, D.D. Doing Meta–Analysis with R: A Hands–On Guide; Chapman & Hall/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-0-367-61007-4. [Google Scholar]

- Radkovsky, A.; McArdle, J.J.; Bockting, C.L.; Berking, M. Successful emotion regulation skills application predicts subsequent reduction of symptom severity during treatment of major depressive disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, E.A.; Moore, M.T.; Kashdan, T.B.; Fresco, D.M. Examination of the factor structure and concurrent validity of the langer mindfulness/mindlessness scale. Assessment 2011, 18, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Cheung, R.Y.M. Testing Interdependent Self-Construal as a Moderator between Mindfulness, Emotion Regulation, and Psychological Health among Emerging Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavez-Baldini, U.; Wichers, M.; Reininghaus, U.; Wigman, J.T.W. Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis Investigators. Expressive suppression in psychosis: The association with social context. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, W. Dispositional mindfulness, perceived social support and emotion regulation among Chinese firefighters: A longitudinal study. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 4079–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingery, J.N.; Bodenlos, J.S.; Schneider, T.I.; Peltz, J.S.; Sindoni, M.W. Dispositional mindfulness predicting psychological adjustment among college students: The role of rumination and gender. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Tan, Y.; Huang, R. Exploring the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and hoarding behavior: A moderated multi-mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 935897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analysis Methods | K | n | Q (df) | P | r | 95% CI | Level 2 I2 | Level 3 I2 | Total I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 32 | 50 | 898.87 (31) | <0.001 | 0.23 | [0.13, 0.33] | 28.2% | 63.05% | 91.25% |

| B | 50 | 1460.65 (49) | <0.001 | 0.23 | [0.14, 0.31] | 97.98% | |||

| C | 23 | 32 | 898.87 (31) | <0.001 | −0.24 | [−0.36, −0.11] | 26.2% | 71.19% | 97.39% |

| D | 38 | 1227.38 (37) | <0.001 | −0.07 | [−0.20, 0.06] | 98.34% | |||

| E | 32 | −0.02 | [−0.19, 0.04] |

| Models | Mindfulness and Cognitive Reappraisal | Mindfulness and Expressive Suppression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | BIC | LRT | p | AIC | BIC | LRT | p | |

| Level (1,2,3) | 35.33 | 41.01 | 15.54 | 19.85 | ||||

| Level (1,2) | 33.25 | 37.04 | 0 | 1 | 27.37 | 30.24 | 13.83 | <0.001 |

| Level (1,3) | 371.87 | 375.65 | 338.54 | <0.001 | 150.03 | 152.91 | 136.48 | <0.001 |

| Meta-Regression Models | K | n | QE(df) | p | b | 95% CI | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness and cognitive reappraisal | ||||||||

| age | 25 | 37 | 1135.85 (35) | <0.001 | 0.06 | [−0.08, 0,19] | F (1,35) = 0.79 | 0.38 |

| culture (Eastern culture as reference) | 32 | 50 | 1357.82 (48) | <0.001 | F (1,48) = 2.30 | 0.14 | ||

| Western culture | 20 | 32 | 0.17 | [−0.05, 0.39] | 0.14 | |||

| gender (women divided by the total number) | 29 | 44 | 1335.28 (42) | <0.001 | −0.02 | [−0.03, 0.00] | F (1,42) = 3.08 | 0.09 |

| mindfulness measurement tools (FFMQ as reference) | 27 | 44 | 1316.74 (42) | <0.001 | F (1,42) = 2.39 | 0.13 | ||

| MAAS | 14 | 19 | −0.16 | [−0.36, 0.05] | 0.13 | |||

| emotion regulation measurement tools (CERQ as reference) | 26 | 42 | 996.88 (40) | <0.001 | F (1,40) = 2.26 | 0.14 | ||

| ERQ | 19 | 29 | 0.23 | [−0.08, 0.53] | 0.14 | |||

| study quality (weak as reference) | 32 | 50 | 1378.05 (47) | <0.001 | F (2,47) = 1.73 | 0.19 | ||

| middle | 16 | 22 | −0.16 | [−0.49, 0.18] | 0.36 | |||

| strong | 4 | 6 | 0.07 | [−0.33, 0.48] | 0.71 | |||

| Mindfulness and expressive suppression | ||||||||

| age | 18 | 27 | 780.80 (25) | <0.001 | 0.01 | [−0.16, 0.14] | F (1,25) = 0.02 | 0.89 |

| culture (Eastern culture as reference) | 23 | 32 | 874.78 (30) | <0.001 | −0.10 | [−0.40, 0.20] | F (1,30) = 0.48 | 0.49 |

| Western culture | −0.10 | [−0.40, 0.20] | 0.49 | |||||

| gender (women divided by the total number) | 20 | 29 | 812.20 (27) | <0.001 | −0.06 | [−0.18, 0.07] | F (1,27) = 0.86 | 0.37 |

| mindfulness measurement tools (FFMQ as reference) | 18 | 26 | 728.19 (24) | <0.001 | F (1,24) = 4.35 | 0.05 | ||

| MAAS | 13 | 14 | −0.35 | [−0.70, −0.01] | 0.05 | |||

| Mindfulness dimension (no-judgment dimension as reference) | 23 | 24 | 521.24 (22) | <0.001 | F (1,22) = 1.22 | 0.28 | ||

| single dimension | 19 | 20 | −0.22 | [−0.62, 0.20] | 0.28 | |||

| study quality (weak as reference) | 23 | 32 | F (2,29) = 0.42 | 0.66 | ||||

| middle | 15 | 21 | 0.04 | [−0.16, 0.23] | 0.69 | |||

| strong | 4 | 6 | −0.10 | [−0.41, 0.20] | 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, S.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X. Linking Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression to Mindfulness: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021241

Zhou S, Wu Y, Xu X. Linking Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression to Mindfulness: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021241

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Senlin, Yunpeng Wu, and Xizheng Xu. 2023. "Linking Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression to Mindfulness: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021241

APA StyleZhou, S., Wu, Y., & Xu, X. (2023). Linking Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression to Mindfulness: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021241