Differences in Characteristics and Length of Stay of Elderly Emergency Patients before and after the Outbreak of COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

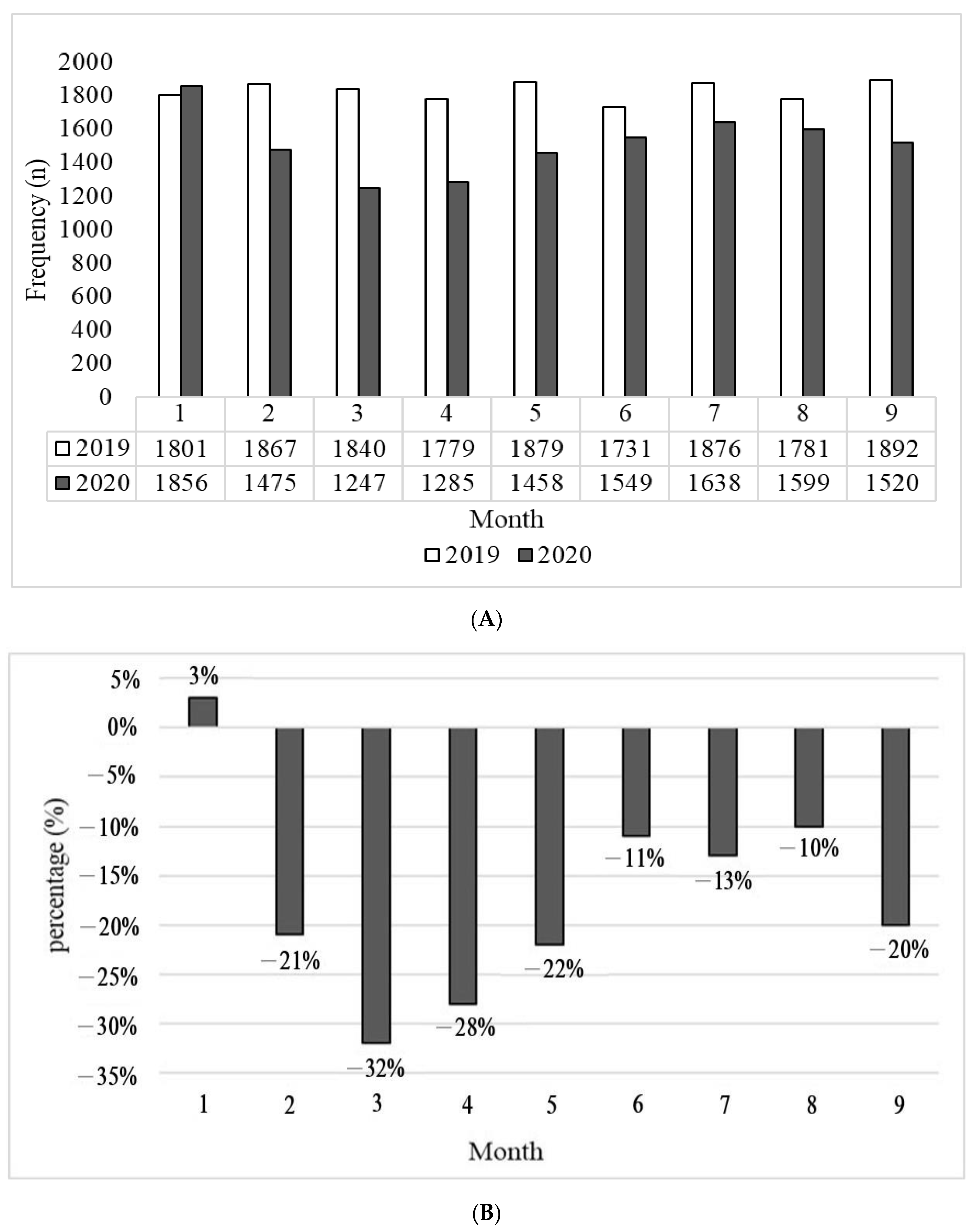

3. Result

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarksat-themedia-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Guo, Y.R.; Cao, Q.D.; Hong, Z.S.; Hong, Z.S.; Tan, Y.Y.; Chen, S.D.; Jin, H.J.; Tan, K.S.; Wang, D.Y.; Yan, Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak—An update on the status. Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; Miao, C.; Yang, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Li, L. Hospital emergency management plan during the COVID-19 epidemic. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.E.; Hawkins, J.E.; Langness, S.; Murrell, K.L.; Iris, P.; Sammann, A. Where are all the patients? Addressing COVID-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care. Nejm Catal. 2020, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, A.K.; Janke, A.T.; Shu-Xia, L.; Rothenberg, C.; Goyal, P.; Terry, A.; Lin, M. Emergency department utilization for emergency conditions during COVID-19. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2021, 78, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett, K.P.; Kite-Powell, A.; DeVies, J.; Coletta, M.A.; Boehmer, T.K.; Adjemian, J.; Gundlapalli, A.V. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019–May 30. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giamello, J.D.; Abram, S.; Bernardi, S.; Lauria, G. The emergency department in the COVID-19 era. Who are we missing? Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagneto-Gissey, L.; Casella, G.; Russo, M.F.; Del Corpo, G.; Iodice, A.; Lattina, I.; Ferrari, P.; Iannone, I.; Mingoli, A.; La Torre, F. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on emergency surgery and emergency department admissions: An Italian level 2 emergency department experience. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, e374–e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.D.; O’Reilly, G.M.; Mitra, B.; Smit, D.V.; Miller, J.P.; Cameron, P.A. Impact of COVID-19 State of Emergency restrictions on presentations to two Victorian emergency departments. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2020, 32, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J. COVID-19: A&E visits in England fall by 25% in week after lockdown. BMJ 2020, 369, m1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnsen, L.P.; Næss-Pleym, L.E.; Dale, J.; Laugsand, L.E. Patient visits to an emergency department in anticipation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tidsskr. Den Nor. Legeforening 2020, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmassani, D.; Tamim, H.; Makki, M.; Hitti, E. The Impact of COVID-19 lockdown measures on ED visits in Lebanon. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 2, 735–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.J.; Ng, C.Y.; Brook, R.H. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA 2020, 323, 1341–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, C.W.; Lu, T.C.; Fang, C.C.; Huang, C.H.; Chen, W.J.; Chen, S.C.; Tsai, C.L. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department services acuity and possible collateral damage. Resuscitation 2020, 153, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcheddu, R.; Serra, C.; Kelvin, D.; Kelvin, N.; Rubino, S. Similarity in case fatality rates (CFR) of COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 in Italy and China. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020, 14, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; He, W.; Yu, X.; Hu, D.; Bao, M.; Liu, H.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, H. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 145–151, (In Chinese, English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe Outcomes Among Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12-March 16. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, B.M.; Hedges, J.R.; Rousseau, E.W.; Sanders, A.B.; Berstein, E.; McNamara, R.M.; Hogan, T.M. Geriatric patient emergency visits part I: Comparison of visits by geriatric and younger patients. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1992, 21, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.A.; Hu, W.H.; Yang, D.Y.; Weng, R.H.; Tsai, W.C. Analysis of emergency department utilization by elderly patients under National Health Insurance. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2003, 19, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.Y.; Chou, S.L.; Chen, L.K.; Yen, H.T.; Hsueh, K.C.; Yen, L.Y. Emergency department utilization by elderly patients. Taiwan Geriatr Gerontol 2007, 2, 225–233, (In Chinese, English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C.J.; Chien, C.Y.; Seak, J.C.; Tsai, S.L.; Weng, Y.M.; Chaou, C.H.; Kuo, C.W.; Chen, J.C.; Hsu, K.H. Validation of the five-tier Taiwan triage and acuity scale for prehospital use by emergency medical technicians. Emerg. Med. J. 2019, 36, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, C.Y.; Yeung, R.S.; Chung, J.Y.; Cameron, P.A. Impact of SARS on an emergency department in Hong Kong. Emerg. Med. 2003, 15, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, L.H.; Chien, C.Y.; Chen, C.B.; Chaou, C.H.; Ng, C.J.; Lo, M.Y.; Seak, C.K.; Seak, J.C.Y.; Goh, Z.N.L.; Seak, C.J. Impact of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic on an Emergency Department Service: Experience at the Largest Tertiary Center in Taiwan. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.H.; Wang, T.L.; Chang, H.; Lee, Y.K. Age-related emergency department utilization: A clue of patient demography in disaster medicine. Ann. Disaster. Med. 2003, 1, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 16,446) | (n = 13,627) | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | 0.391 | ||

| Male | 9058 (55.1) | 7438 (54.6) | |

| Female | 7388 (44.9) | 6189 (45.4) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 65–74 | 6902 (42.0) | 5828 (42.8) | 0.343 |

| 75–84 | 5325 (32.4) | 4326 (31.7) | |

| ≥85 | 4219 (25.7) | 3473 (25.5) | |

| Triage | 0.138 | ||

| 1 | 1286 (7.8) | 1107 (8.1) | |

| 2 | 4238 (25.8) | 3570 (26.2) | |

| 3 | 10,673 (64.9) | 8702 (63.9) | |

| 4 | 226 (1.4) | 223 (1.6) | |

| 5 | 23 (0.1) | 25 (0.2) | |

| Disposition | 0.000 | ||

| Discharge | 9156 (55.7) | 6851 (50.3) | |

| Transfer to the general ward | 5835 (35.5) | 5461 (40.1) | |

| Against advice discharge | 658 (4.0) | 541 (4.0) | |

| Transfer to intensive care unit | 546 (3.3) | 520 (3.8) | |

| Transfer to other hospitals | 91 (0.6) | 65 (0.5) | |

| Self-discharge | 26 (0.2) | 9 (0.1) | |

| Died in ED | 134 (0.8) | 180 (1.3) |

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 5835) | (n = 5461) | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Bed request | 0.295 | ||

| Internal medicine | 5264 (90.2) | 4878 (89.3) | |

| Surgery | 471 (8.1) | 482 (8.8) | |

| Others | 100 (1.7) | 101 (1.8) |

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean ± SD (h) | n | Mean ± SD (h) | ||

| Emergency treatment outcome | |||||

| Non-hospitalization | 10,065 | 9.1 ± 16.0 | 7646 | 6.7 ± 10.9 | 0.000 |

| Hospitalization | 6381 | 27.4 ± 25.9 | 5981 | 18.0 ± 16.6 | 0.000 |

| Transfer to the general ward | 5835 | 28.5 ± 26.2 | 5461 | 18.4 ± 16.6 | 0.000 |

| Transfer to intensive care unit | 546 | 15.6 ± 18.7 | 520 | 14.0 ± 16.5 | 0.137 |

| Bed request | |||||

| Internal medicine | 5264 | 30.0 ± 26.7 | 4878 | 19.1 ± 16.9 | 0.000 |

| Surgery | 471 | 15.4 ± 16.0 | 482 | 13.4 ± 12.5 | 0.026 |

| Others | 100 | 10.3 ± 10.1 | 101 | 10.2 ± 12.0 | 0.942 |

| Before COVID-19 (n = 16,446) | During COVID-19 (n = 13,627) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | n (%) | Mean ± SD (h) | Diagnosis | n (%) | Mean ± SD (h) | |

| Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings not elsewhere classified | 5710 (34.7) | 13.5 ± 19.7 | Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings not elsewhere classified | 4097 (30.1) | 9.6 ± 12.9 | 0.000 |

| Neoplasms | 1716 (10.4) | 15.4 ± 20.4 | Neoplasms | 1846 (13.5) | 12.0 ± 14.3 | 0.000 |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 1656 (10.1) | 16.5 ± 21.8 | Diseases of the circulatory system | 1546 (11.3) | 12.8 ± 16.6 | 0.000 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 1644 (10.0) | 20.4 ± 26.3 | Diseases of the genitourinary system | 1380 (10.1) | 14.8 ± 16.2 | 0.000 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 1364 (8.3) | 21.1 ± 24.9 | Diseases of the respiratory system | 1050 (7.7) | 15.5 ± 17.3 | 0.000 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 1266 (7.7) | 18.6 ± 21.8 | Diseases of the digestive system | 852 (6.3) | 13.7 ± 15.6 | 0.000 |

| Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 611 (3.7) | 25.6 ± 26.3 | Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 446 (3.3) | 14.9 ± 14.1 | 0.000 |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 550 (3.3) | 9.1 ± 16.9 | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 426 (3.1) | 8.0 ± 12.8 | 0.279 |

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 466 (2.8) | 20.7 ± 29.6 | Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 409 (3.0) | 12.5 ± 23.0 | 0.000 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 462 (2.8) | 8.8 ± 21.7 | Diseases of the nervous system | 262 (1.9) | 8.9 ± 12.0 | 0.004 |

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | OR | 95% CI for OR | p-Value | OR | 95% CI for OR | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Sex (ref: Female) | ||||||||

| Male | 0.000 | 1.180 *** | 1.084 | 1.285 | 0.012 | 1.146 * | 1.031 | 1.273 |

| Age (years) (ref: 65–74) | ||||||||

| 75–84 | 0.027 | 1.119 * | 1.013 | 1.235 | 0.045 | 1.133 * | 1.003 | 1.281 |

| ≥85 | 0.000 | 1.360 *** | 1.227 | 1.507 | 0.312 | 1.069 | 0.940 | 1.216 |

| Triage (ref: 4) | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.149 | 0.661 | 0.377 | 1.160 | 0.769 | 1.102 | 0.578 | 2.099 |

| 2 | 0.380 | 1.278 | 0.739 | 2.212 | 0.637 | 1.164 | 0.619 | 2.189 |

| 3 | 0.010 | 2.040 ** | 1.185 | 3.512 | 0.157 | 1.570 | 0.840 | 2.935 |

| Bed request (ref: Non-hospitalization) | ||||||||

| Internal medicine | 0.000 | 10.376 *** | 9.462 | 11.378 | 0.000 | 7.065 *** | 6.246 | 7.990 |

| Surgery | 0.000 | 2.088 *** | 1.663 | 2.622 | 0.000 | 2.872 *** | 2.220 | 3.715 |

| Others | 0.258 | 1.470 | 0.754 | 2.867 | 0.762 | 0.836 | 0.262 | 2.671 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juang, W.-C.; Chiou, S.M.-J.; Chen, H.-C.; Li, Y.-C. Differences in Characteristics and Length of Stay of Elderly Emergency Patients before and after the Outbreak of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021162

Juang W-C, Chiou SM-J, Chen H-C, Li Y-C. Differences in Characteristics and Length of Stay of Elderly Emergency Patients before and after the Outbreak of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021162

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuang, Wang-Chuan, Sonia Ming-Jiu Chiou, Hsien-Chih Chen, and Ying-Chun Li. 2023. "Differences in Characteristics and Length of Stay of Elderly Emergency Patients before and after the Outbreak of COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021162

APA StyleJuang, W.-C., Chiou, S. M.-J., Chen, H.-C., & Li, Y.-C. (2023). Differences in Characteristics and Length of Stay of Elderly Emergency Patients before and after the Outbreak of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021162