Intercity Mobility Assessment Facing the Demographic Challenge: A Survey-Based Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology for Calculating Accessibility in the RMSC (Network Analysis)

2.3. Length, Procedure and Survey Structure

2.4. Sample Size

3. Results

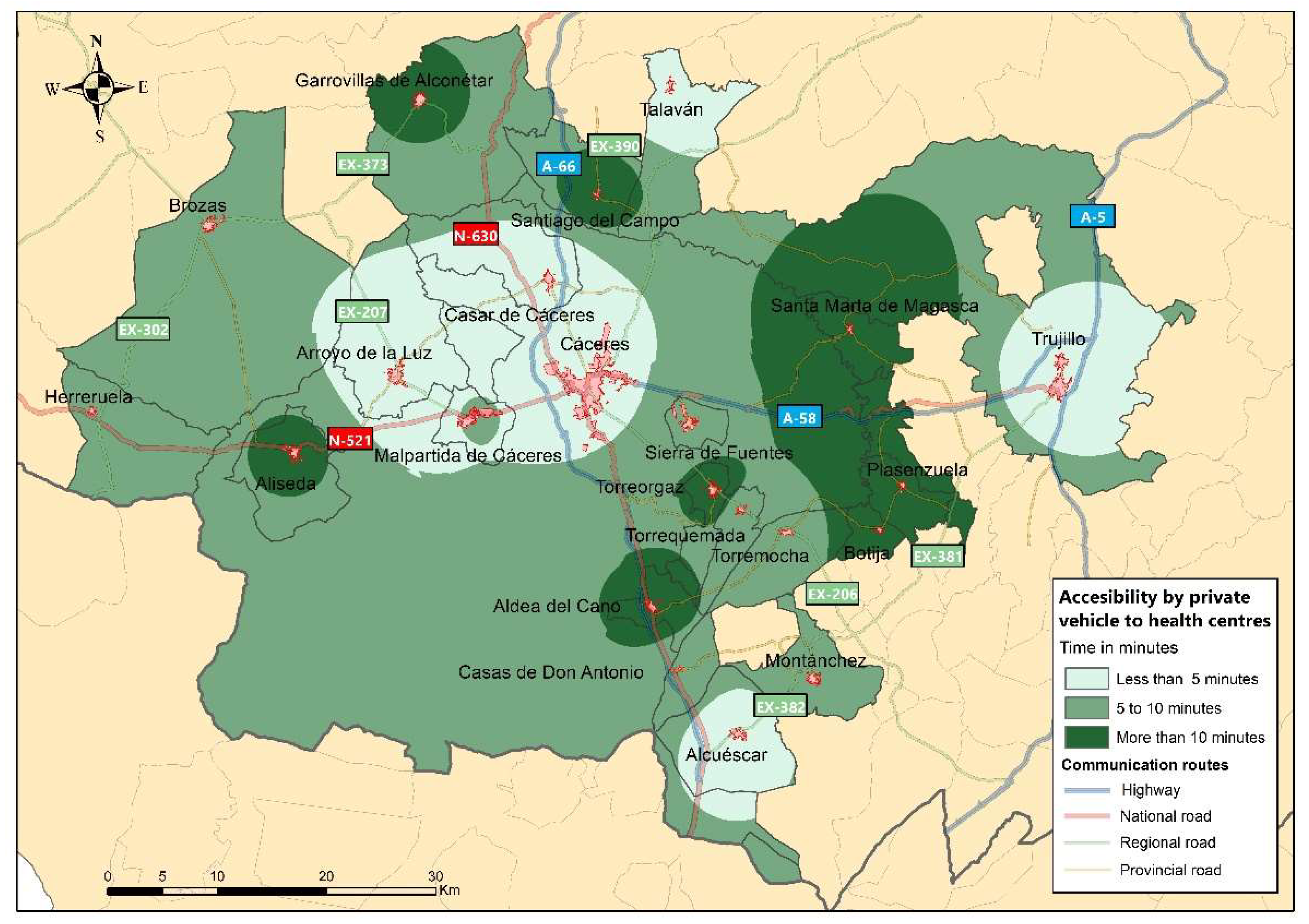

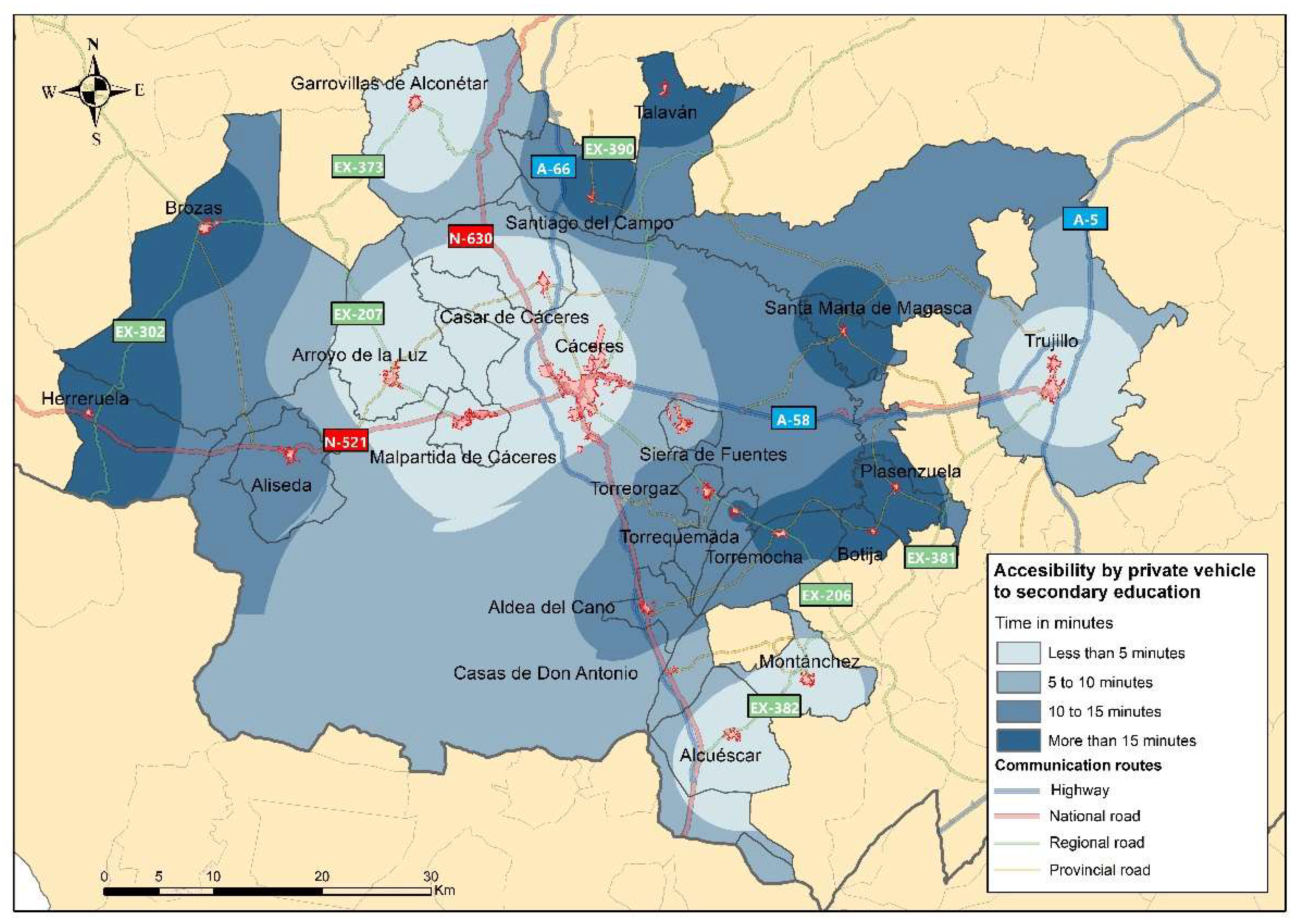

3.1. Analysis of the Accessibility of the RMSC Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

3.1.1. General Accessibility of the Rural Municipalities of the RMSC to the City of Cáceres

3.1.2. Accessibility of the RMSC to Health Centres

3.1.3. Accessibility of the RMSC to Secondary Schools

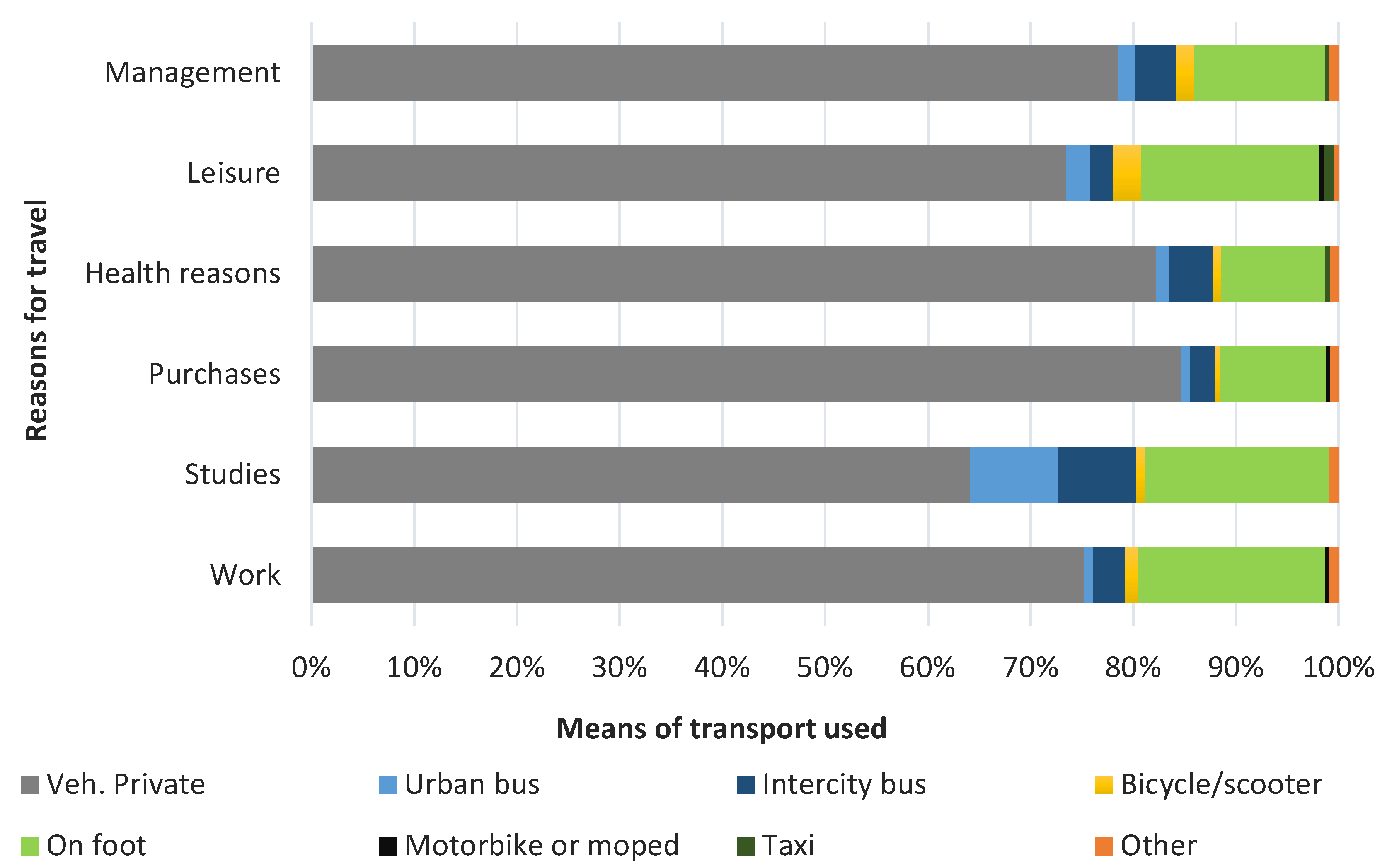

3.2. Preference Poll Results Revealed

3.2.1. Means of Transport Used

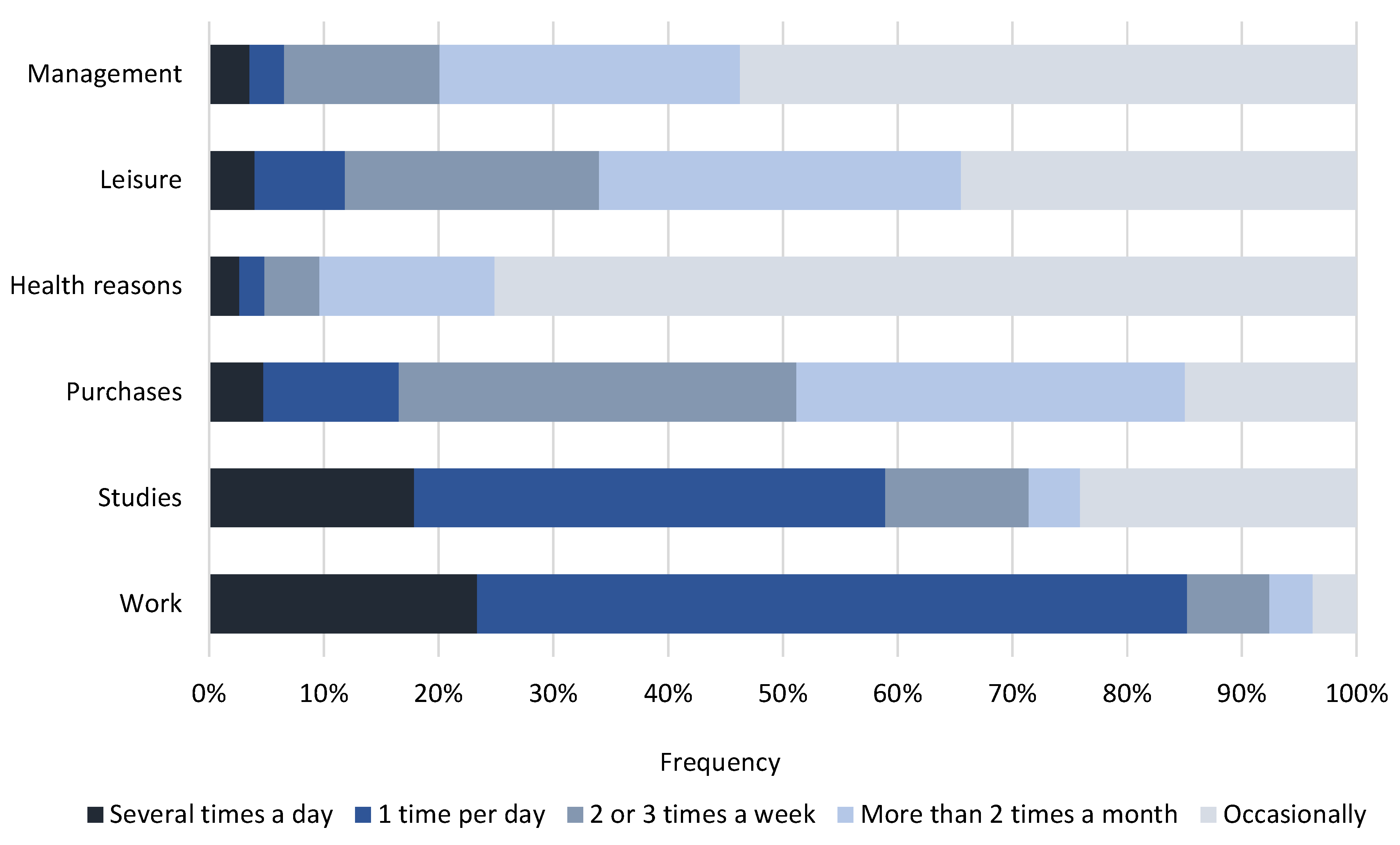

3.2.2. Frequency of Travel

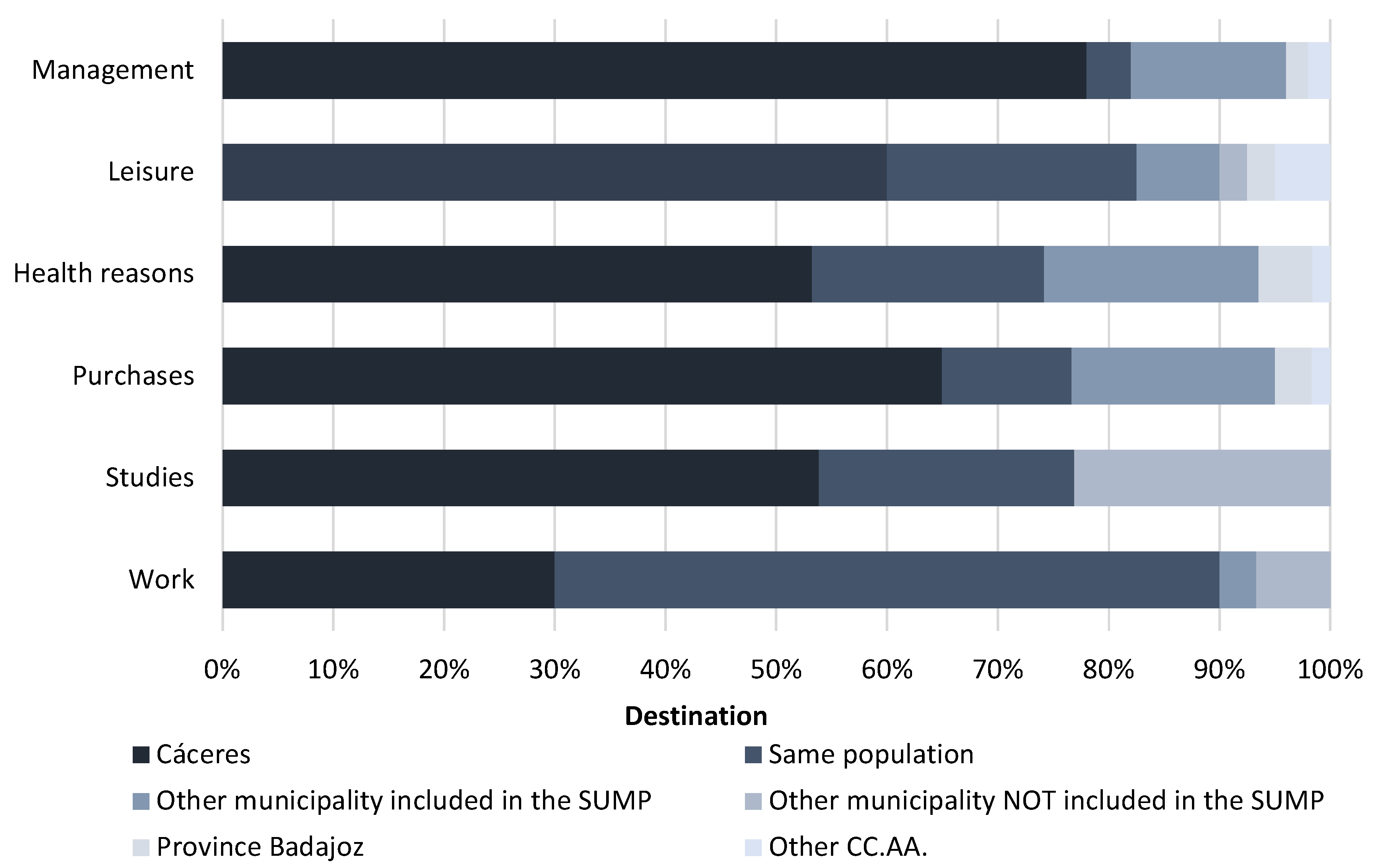

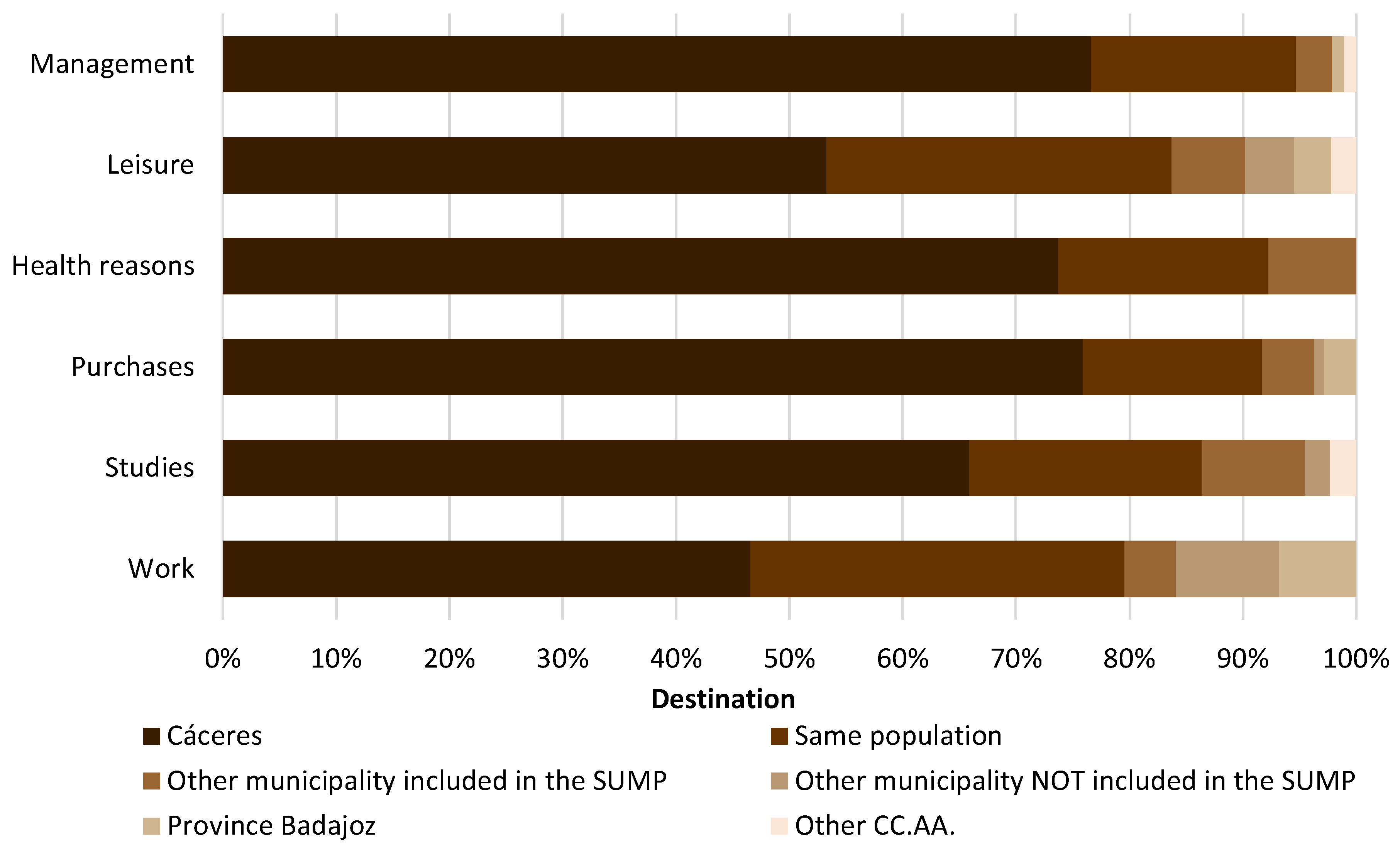

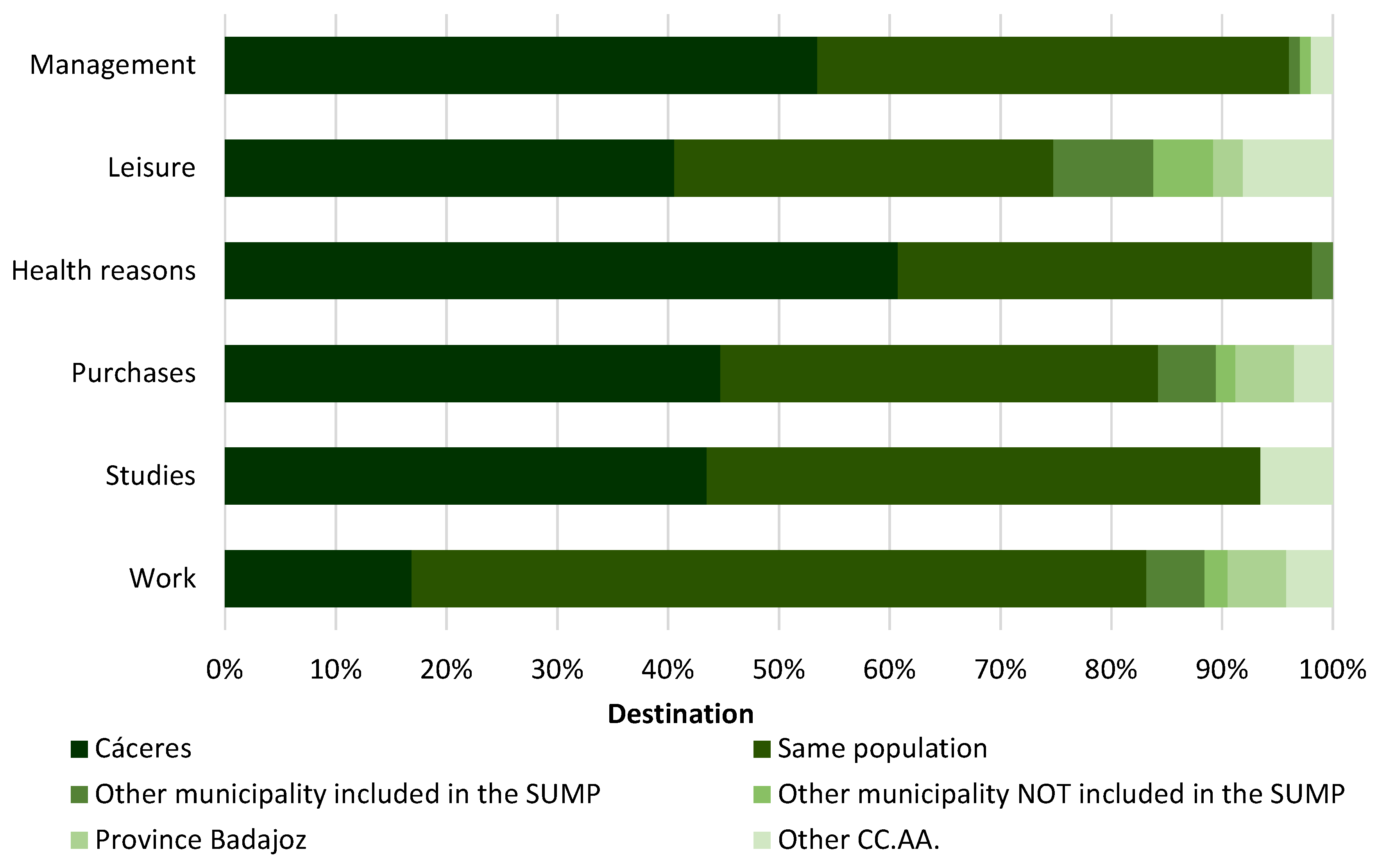

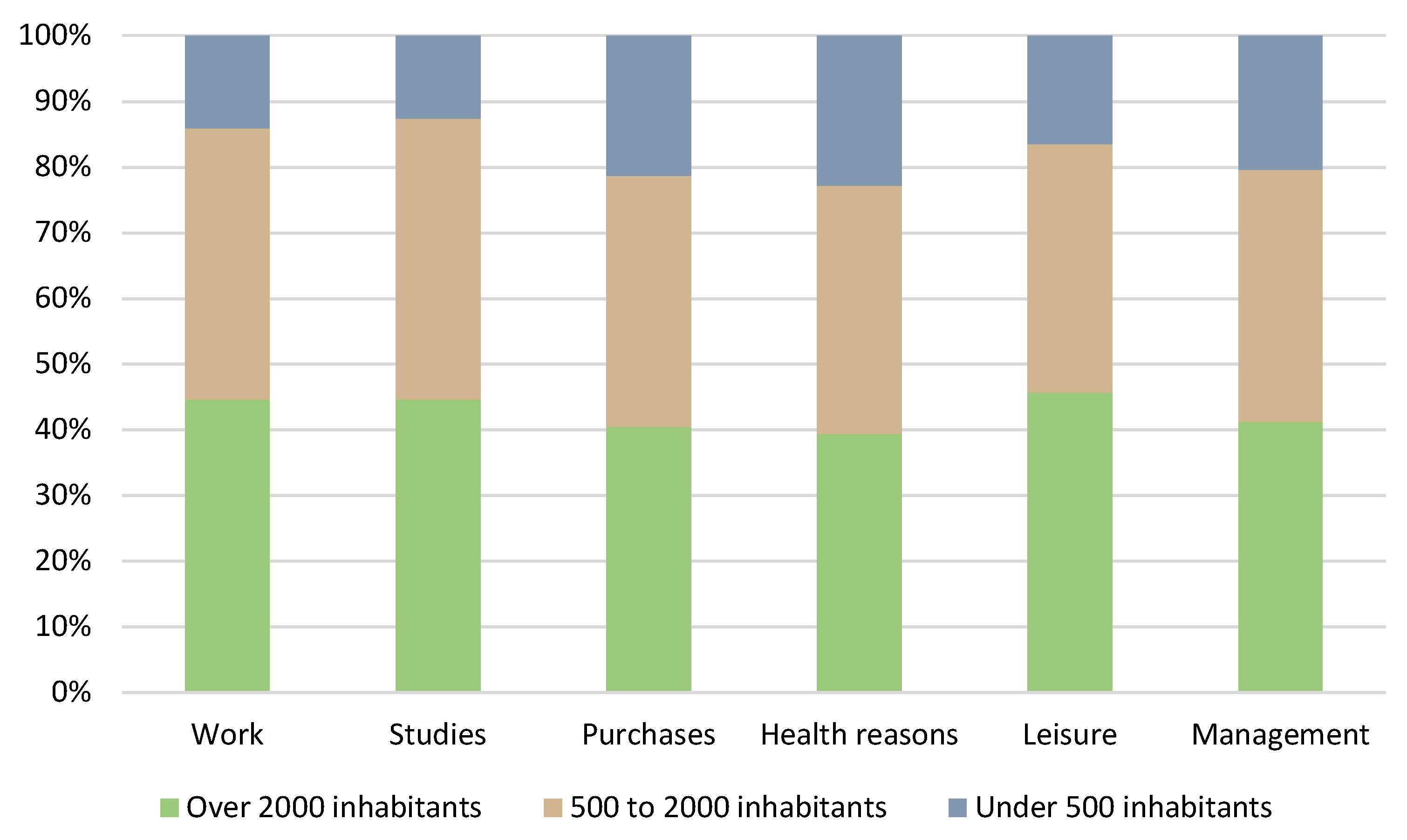

3.2.3. Connectivity of Municipalities by Population Range

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez Giménez, J.M.; de Sá Marques, T.V.; Hernández Aja, A. Procesos Urbanos Funcionales En Iberia: Una Aproximación a La Integración Del Territorio Urbano Más Allá de La Metropolización. Cuad. Geográficos 2020, 59, 93–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Energy, Transport and Environment Statistic; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Ihlström, J. The Importance of Public Transport for Mobility and Everyday Activities among Rural Residents. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, K. Rural-Urban Interdependencies: Thinking through the Implications of Space, Leisure, Politics and Health. Leis. Sci. 2021, 43, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Espada, M.; Naranjo, J.M.V.; García, F.M.M. Identification of Mobility Patterns in Rural Areas of Low Demographic Density through Stated Preference Surveys. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu, G.; Sanz, A. Public Policies to Promote Sustainable Transports: Lessons from Valencia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozos-Blanco, M.Á.; Pozo-Menéndez, E.; Arce-Ruiz, R.; Baucells-Aletà, N. The Way to Sustainable Mobility. A Comparative Analysis of Sustainable Mobility Plans in Spain. Transp. Policy 2018, 72, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeschger, G.; Carroll, P.; Caulfield, B. Micromobility and Public Transport Integration: The Current State of Knowledge. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 89, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, D.; Fadyushin, A. The Efficiency of Some Activities for the Development of Urban Infrastructure for Public Transport, Cyclists and Pedestrians. Int. J. Transp. Dev. Integr. 2021, 5, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Kumakoshi, Y.; Fan, Y.; Milardo, S.; Koizumi, H.; Santi, P.; Murillo Arias, J.; Zheng, S.; Ratti, C. Street Pedestrianization in Urban Districts: Economic Impacts in Spanish Cities. Cities 2022, 120, 103468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.L.; Xing, Y. Factors Correlated with Bicycle Commuting: A Study in Six Small U.S. Cities. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2011, 5, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emond, C.R.; Handy, S.L. Factors Associated with Bicycling to High School: Insights from Davis, CA. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 20, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, N.; Monzon, A. Towards Low-Carbon Interurban Road Strategies: Identifying Hot Spots Road Corridors in Spain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarass, J.; Heinrichs, D. New Urban Living and Mobility. Transp. Res. Procedia 2014, 1, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Álvarez, A.; Soria-Lara, J.A.; Arce-Ruiz, R.M.; López-Lambas, M.E.; Jimenez-Espada, M. Experimenting with Scenario-Building Narratives to Integrate Land Use and Transport. Transp. Policy 2021, 101, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera, R.; Soria, J.A.; Valenzuela, L.M. La Calidad Peatonal Como Método Para Evaluar Entornos de Movilidad Urbana. Doc. D’anàlisi Geogràfica 2014, 60, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzon, A. Integrated Policies for Improving Modal Split in Urban Areas. In Proceedings of the 16th International Symposium on Theory and Practice in Transport Economics, Budapest, Hungary, 29–31 October 2003; p. 553. [Google Scholar]

- Al Shammas, T.; Ambiente, M. Caminabilidad En Las Aceras de Madrid; Universidad de Alcalá: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DuPuis, N.; Griess, J.; Klein, C. Micromobility in Cities: A History and Policy Overview; National League of Cities: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- López-Lambas, M.E.; Sánchez, J.M.; Alonso, A. The Walking Health: A Route Choice Model to Analyze the Street Factors Enhancing Active Mobility. J. Transp. Health 2021, 22, 101133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinella, G. Considering Cycling for Commuting: The Role of Mode Familiarity. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simsekoglu, Ö.; Klöckner, C. Factors Related to the Intention to Buy an E-Bike: A Survey Study from Norway. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 60, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oña, J.; Estévez, E.; de Oña, R. How Does Private Vehicle Users Perceive the Public Transport Service Quality in Large Metropolitan Areas? A European Comparison. Transp. Policy 2021, 112, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, V.; Garau, C.; Inturri, G.; Ignaccolo, M. Strategies and Actions towards Sustainability: Encouraging Good ITS Practices in the SUMP Vision. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2343, 90008. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenio, E.; Martens, K.; Di Ciommo, F. Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans: Bridging Climate Change and Equity Targets? Res. Transp. Econ. 2016, 55, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Para la Diversificación y Ahorro de la Energía. PMUS: Guía Práctica Para La Elaboración e Implantación de Planes de Movilidad Urbana Sostenible; IDAE: Madrid, Spain, 2006; ISBN 9788486850982.

- Barberan, A.; Monzon, A. How Did Bicycle Share Increase in Vitoria-Gasteiz? Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 18, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya-Jariego, I.; Holgado, D. Living in the Metropolitan Area. Correlation of Interurban Mobility with the Structural Cohesion of Personal Networks and the Originative Sense of Community. Psychosoc. Interv. 2015, 24, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigazzi, A.; Wong, K. Electric Bicycle Mode Substitution for Driving, Public Transit, Conventional Cycling, and Walking. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 85, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Monzón, A.; Alonso, A.; Julio, R. Potential Demand for Bus Commuting Trips in Metropolitan Corridors through the Use of Real-Time Information Tools. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2021, 16, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Heredia, Á.; Monzón, A.; Jara-Díaz, S. Understanding Cyclists’ Perceptions, Keys for a Successful Bicycle Promotion. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2014, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J. Examining the Process of Modal Choice for Everyday Travel among Older People. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.; Dirks, N.; Walther, G. Improving Rural Accessibility by Locating Multimodal Mobility Hubs. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 94, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, A.; Tóth, J.; Mándoki, P. Demand Responsive Transport Service of “Dead-End Villages” in Interurban Traffic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer, D.C.; Krams, B.; Körner, M.; Hantsch, F.; Martin, U.; Herzwurm, G. Electric Vehicles in Rural Demand-Responsive Systems: Findings of Two Demand Responsive Transport Projects for the Improvement of Service Provision. World Electr. Veh. J. 2018, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasencia-Lozano, P. Evaluation of a New Urban Cycling Infrastructure in Caceres (Spain). Sustainability 2021, 13, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascajo, R.; Lopez, E.; Herrero, F.; Monzon, A. User Perception of Transfers in Multimodal Urban Trips: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019, 13, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, P.K.; Stancato, D.M.; Cotêb, S.; Mendoza-Denton, R.; Keltner, D. Higher Social Class Predicts Increased Unethical Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4086–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Romo, G.; Garrido-Muñoz, M.; Lucía, A.; Mayorga, J.I.; Ruiz, J.R. Asociación Entre Las Características Del Entorno de Residencia y La Actividad Física. Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acheampong, R.A.; Siiba, A. Examining the Determinants of Utility Bicycling Using a Socio-Ecological Framework: An Exploratory Study of the Tamale Metropolis in Northern Ghana. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 69, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudde, A. The Unequal Cycling Boom in Germany. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 98, 103244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois, D.; Monzón, A.; Hernández, S. Analysis of Satisfaction Factors at Urban Transport Interchanges: Measuring Travellers’ Attitudes to Information, Security and Waiting. Transp. Policy 2018, 67, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Ortuño, R. La Regulación de Los Semáforos Peatonales En España: ¿tienen Las Personas Mayores Tiempo Suficiente Para Cruzar? Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, E.; Ayllon, E.; Eito, M.Á.; Lozano, A.; Martínez, S.; Bañares, L.; Vicén, M.J.; Moreno, P. The City of Girls and Boys of Huesca (Spain), an Opportunity for Designing Healthy Environment and Public Policies. Gac. Sanit. 2019, 33, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, J.; Rose, G.; Lo, S.K. Promoting Transportation Cycling for Women: The Role of Bicycle Infrastructure. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquet, O.; Hipp, J.A.; Miralles-Guasch, C. Neighborhood Walkability and Active Ageing: A Difference in Differences Assessment of Active Transportation over Ten Years. J. Transp. Health 2017, 7, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, B. Livable Streets for Schoolchildren: A Human-Centred Understanding of the Cognitive Benefits of Safe Routes to School. J. Urban Des. 2022, 27, 692–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vich, G.; Marquet, O.; Miralles-Guasch, C. Green Streetscape and Walking: Exploring Active Mobility Patterns in Dense and Compact Cities. J. Transp. Health 2019, 12, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Guasch, C.; Dopico, J.; Delclòs-Alió, X.; Knobel, P.; Marquet, O.; Maneja-Zaragoza, R.; Schipperijn, J.; Vich, G. Natural Landscape, Infrastructure, and Health: The Physical Activity Implications of Urban Green Space Composition among the Elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Almatar, K.M. Transit-Oriented Development in Saudi Arabia: Riyadh as a Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Abdullah, M.; Javid, M.A. Accessibility-Based Approach: Shaping Travel Needs in Pandemic Situation for Planners’ Perspectives. Eng. J. 2021, 25, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschmann, E.E.; Kwan, M.P. Toward Socially Sustainable Urban Transportation: Progress and Potentials. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2008, 2, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badassa, B.B.; Sun, B.; Qiao, L. Sustainable Transport Infrastructure and Economic Returns: A Bibliometric and Visualization Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishar, A.; Št’Astná, M. Accessibility of Services in Rural Areas: Southern Moravia Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diputación de Cáceres. Estrategia de Desarrollo Urbano Sostenible e Integrador de La Red de Municipios Sostenibles de Cáceres (RMSC); Diputación de Cáceres: Cáceres, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Porru, S.; Misso, F.E.; Pani, F.E.; Repetto, C. Smart Mobility and Public Transport: Opportunities and Challenges in Rural and Urban Areas. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. Engl. Ed. 2020, 7, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüchert, T.; Hasselder, P.; Quentin, P.; Bolte, G. Walking for Transport among Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study on the Role of the Built Environment in Less Densely Populated Areas in Northern Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzulla, G.; Bellizzi, M.G.; Eboli, L.; Forciniti, C. Cycling for a Sustainable Touristic Mobility: A Preliminary Study in an Urban Area of Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Martínez, A. Modelización de La Penalización Del Transbordo En Transporte Público: Un Enfoque Cualitativo y Cuantitativo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibeas, A.; González, F.; Dell’Olio, L.; Moura, J. Manual de Encuestas de Movilidad: Preferencias Declaradas; CreateSpace Independent Publishing: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1511877473. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Pintor, J.M.; Jiménez Espada, M. Percepción de La Movilidad En El Contexto Universitario. In Plan de Movilidad Sostenible de la Universidad de Extremadura, Diagnóstico de la Movilidad en los Campus de la Universidad de Extremadura; Universidad de Extremadura: Merida, Spain, 2018; pp. 99–118. ISBN 978-84-697-8322-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Rodríguez, J.; Luque-Sendra, A.; de las Heras, A.; Zamora-Polo, F. Analysis of Interurban Mobility in University Students: Motivation and Ecological Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, T.S.; Jiang, X.; Sun, Y.; Yu, J.Z. A Space-Time Analysis of Rural Older People’s Outdoor Mobility and Its Impact on Self-Rated Health: Evidence from a Taiwanese Rural Village. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Alonso, G.C. Research on the Accessibility to Health and Educational Services in the Rural Areas in Extremadura. Eur. Countrys. 2015, 7, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.M. GIS and Network Analysis. In Proceedings of the 43rd Congress of the European Regional Science Association: “Peripheries, Centres, and Spatial Development in the New Europe”, Jyväskylä, Finland, 27–30 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, H.J.; Wu, Y.H. GIS Software for Measuring Space-Time Accessibility in Transportation Planning and Analysis. Geoinformatica 2000, 4, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Espada, M.; Cuartero, A.; Breton, M. Le Sustainability Assessment through Urban Accessibility Indicators and GIS in a Middle-Sized World Heritage City: The Case of Cáceres, Spain. Buildings 2022, 12, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Kang, S.; Lee, G.; Kim, J.; Park, D. Identifying the Spatial Structure of the Tourist Attraction System in South Korea Using GIS and Network Analysis: An Application of Anchor-Point Theory. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Yoo, S.H.; Oh, Y.G. Evaluating Spatial Centrality for Integrated Tourism Management in Rural Areas Using GIS and Network Analysis. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ibrahim, R.F.; Hefny, H.A. GIS-Based Network Analysis for the Roads Network of the Greater Cairo Area. In Proceedings of the CEUR, 2nd International Conference on Applied Research in Computer Science and Engineering, Beirut, Lebanon, 22–23 June 2017; Volume 2144. [Google Scholar]

- Athira, G.; Bahurudeen, A.; Vishnu, V.S. Availability and Accessibility of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash for Its Utilization in Indian Cement Plants: A GIS-Based Network Analysis. Sugar Tech 2020, 22, 1038–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de Espana. Junta de Extremadura Ley 11/2018 de Ordenación Territorial y Urbanística Sostenible de Extremadura (LOTUS). Boletín Of. Del Estado 2019, 35, 12436–12570. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de Espana. Junta de Extremadura Decreto 143/2021, de 21 de Diciembre, Por El Que Se Aprueba El Reglamento General de La Ley de Ordenación Territorial y Urbanística Sostenible de Extremadura. Boletín Of. Del Estado 2021, 248, 61778–62041. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Espada, M.; Martínez García, F.M.; González-Escobar, R. Urban Equity as a Challenge for the Southern Europe Historic Cities: Sustainability-Urban Morphology Interrelation through GIS Tools. Land 2022, 11, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Brunsdon, C.; Green, E. Using a GIS-Based Network Analysis to Determine Urban Greenspace Accessibility for Different Ethnic and Religious Groups. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 86, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, G.F.; Bailey, A.J. Distance and Health Care Utilization among the Rural Elderly. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranković Plazinić, B.; Jović, J. Mobility and Transport Potential of Elderly in Differently Accessible Rural Areas. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 68, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos Otón, M.; Alonso Logroño, M. del P. La Movilidad Laboral Diaria: Contrastes Territoriales En El Eje Atlántico Gallego. Ería Rev. Cuatrimest. Geogr. 2009, 78–79, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mounce, R.; Beecroft, M.; Nelson, J.D. On the Role of Frameworks and Smart Mobility in Addressing the Rural Mobility Problem. Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 83, 100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzon, A.; Vega, L.A.; Lopez-Lambas, M.E. Potential to Attract Drivers out of Their Cars in Dense Urban Areas. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2011, 3, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.; Monzón, A.; Cascajo, R. Comparative Analysis of Passenger Transport Sustainability in European Cities. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 48, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Extremadura. Estrategia Ante El Reto Demográfico y Territorial de Extremadura; Junta de Extremadura: Merida, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Size | Municipalities | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Under 500 inhabitants | Botija, Casas de Don Antonio, Herreruela, Plasenzuela, Santa Marta de Magasca and Santiago del Campo | 1694 |

| 500 to 2000 inhabitants | Aldea del Cano, Aliseda, Brozas, Montánchez, Sierra de Fuentes, Talaván, Torremocha, Torreorgaz and Torrequemada | 11,664 |

| Over 2000 inhabitants | Alcuéscar, Arroyo de la Luz, Casar de Cáceres, Garrovillas de Alconétar, Malpartida de Cáceres and Trujillo. | 28,022 |

| Category | Subcategory | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 105 | 35.71% |

| Woman | 187 | 63.61% | |

| I prefer not to say | 2 | 0.68% | |

| Age | 20–29 | 26 | 8.84% |

| 30–39 | 43 | 14.63% | |

| 40–49 | 75 | 25.51% | |

| 50–59 | 85 | 28.91% | |

| 60–69 | 37 | 12.59% | |

| 70–79 | 24 | 8.16% | |

| 80–89 | 4 | 1.36% | |

| Employment status | In retirement or early retirement | 52 | 17.75% |

| Unemployed | 29 | 9.90% | |

| Studying | 8 | 2.73% | |

| Other situation or inactivity | 13 | 4.44% | |

| Household chores | 18 | 6.14% | |

| Working | 174 | 59.04% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vega Naranjo, J.M.; Jiménez-Espada, M.; Martínez García, F.M.; González-Escobar, R.; Cortés-Pérez, J.P. Intercity Mobility Assessment Facing the Demographic Challenge: A Survey-Based Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021163

Vega Naranjo JM, Jiménez-Espada M, Martínez García FM, González-Escobar R, Cortés-Pérez JP. Intercity Mobility Assessment Facing the Demographic Challenge: A Survey-Based Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(2):1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021163

Chicago/Turabian StyleVega Naranjo, Juan Miguel, Montaña Jiménez-Espada, Francisco Manuel Martínez García, Rafael González-Escobar, and Juan Pedro Cortés-Pérez. 2023. "Intercity Mobility Assessment Facing the Demographic Challenge: A Survey-Based Research" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 2: 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021163

APA StyleVega Naranjo, J. M., Jiménez-Espada, M., Martínez García, F. M., González-Escobar, R., & Cortés-Pérez, J. P. (2023). Intercity Mobility Assessment Facing the Demographic Challenge: A Survey-Based Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021163