The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Academic Satisfaction among Sexual Minority College Students: The Indirect Effect of Flourishing

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cyberbullying and LGBTQ College Students’ Academic Satisfaction

1.2. Effect of Flourishing on Cyberbullying and Academic Satisfaction in LGBTQ College Students

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations and Implications for Research

5.2. Practice Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.M.; Hong, J.S.; Yoon, J.; Peguero, A.A.; Seok, H.J. Correlates of adolescent cyberbullying in South Korea in multiple contexts: A review of the literature and implications for research and school practice. Deviant Behav. 2017, 39, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying, 2nd ed.; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Oudekerk, B.A. Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2019 (NCES 2020-063/NCJ 254485); National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Angoff, H.D.; Barnhart, W.R. Bullying and cyberbullying among LGBQ and heterosexual youth from an intersectional perspective: Findings from the 2017 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J. Sch. Violence 2021, 20, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Bias-based cyberbullying among early adolescents: Associations with cognitive and affective empathy. J. Early Adolesc. J. 2022, 42, 1204–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboujaoude, E.; Savage, M.W.; Starcevic, V.; Salame, W.O. Cyberbullying: Review of an old problem gone viral. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, R.L.; Kenny, M.C. Cyberbullying and LGBTQ youth: A systematic literature review and recommendations for prevention and intervention. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2018, 11, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being; Atria Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, P.J.; Sandage, S.J.; Bell, C.A.; Davis, D.E.; Porter, E.; Jessen, M.; Motzny, C.L.; Ross, K.V.; Owen, J. Virtue, flourishing, and positive psychology in psychotherapy: An overview and research prospectus. Psychotherapy 2020, 57, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y. Understanding the purpose of higher education: An analysis of the economic and social benefits for completing a college degree. JEPA 2016, 6, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hout, M. Social and economic returns to college education in the United States. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2012, 38, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Pressured into Crime: An Overview of General Strain Theory; Roxbury: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.M.; Cho, S.; Peguero, A.A.; Misuraca, J.A. From bullying victimization to delinquency in South Korean adolescents: Exploring the pathways using a nationally representative sample. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 98, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.E.; D’Alessio, S.J.; Stolzenberg, L. The effect of social, verbal, physical, and cyberbullying victimization on academic performance. Vict. Offenders 2020, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Seligman, M.E. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.M.; Choi, H.H.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Lee, J. The impact of cyberbullying victimization on psychosocial behaviors among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The indirect effect of a sense of purpose in life. J. Aggress Maltreatment Trauma 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, T.L.; Bolognino, S.J. The College Student Subjective Well-being Questionnaire: A brief, multidimensional measure of undergraduate’s covitality. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, T.; Li, Q. The relationship between cyberbullying and school bullying. J. Stud. Wellbeing 2007, 1, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myburgh, C.; Poggenpoel, M. Meta-synthesis on learner’s experience of aggression in secondary schools in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2009, 29, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strøm, I.F.; Thoresen, S.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Dyb, G. Violence, bullying and academic achievement: A study of 15-year-old adolescents and their school environment. Child Abuse Negl. 2013, 37, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Delgado, B.; Garcia-Fernandez, J.M.; Ruiz-Esteban, C. Cyberbullying in the university setting: Relationship with emotional problems and adaptation to the university. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peled, Y. Cyberbullying and its influence on academic, social, and emotional development of undergraduate students. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Mahdavi, J.; Carvalho, M.; Fisher, S.; Russell, S.; Tippett, N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Dillon, S. Influence of cyberbullying behaviour on the academic achievement of college going students. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 3049–3054. [Google Scholar]

- Abinayaa, M.; Nithya, R. Impact of cyberbullying victimization, depression, perceived coping self efficacy and psychological flourishing among college students. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2022, 10, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Rendón, R.; Pérez-Villalobos, M.V.; Páez-Rovira, D.; Gracia-Leiva, M. A longitudinal study: Affective wellbeing, psychological wellbeing, self-efficacy and academic performance among first-year undergraduate students. Scand. J. Psychol. 2020, 61, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giumetti, G.W.; Kowalski, R.M. Cyberbullying via social media and well-being. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 45, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenaro, C.; Flores, N.; Frías, C.P. Anxiety and depression in cyberbullied college students: A retrospective study. J. Interpers Violence 2021, 36, 579–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, J.L.; DiLalla, L.F.; McCrary, M.K. Cyber victimization and depressive symptoms in sexual minority college students. J. Sch. Violence 2016, 15, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, X.; Wang, X.; Lei, L.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, S. Cyberbullying and depression among Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model of social anxiety and neuroticism. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosciw, J.G.; Palmer, N.A.; Kull, R.M.; Greytak, E.A. The effect of negative school climate on academic outcomes for LGBT youth and the role of in-school supports. J. Sch. Violence 2013, 12, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, S.B.; Wyatt, T.J. Sexual orientation and differences in mental health, stress, and academic performance in a national sample of U.S. college students. J. Homosex 2011, 58, 1255–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosciw, J.G.; Palmer, N.A.; Kull, R.M. Reflecting resiliency: Openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 55, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 39, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schotanus-Dijkstra, M.; Pieterse, M.E.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Westerhof, G.J.; de Graaf, R.; ten Have, M.; Walburg, J.A.; Bohlmeijer, E.T. What factors are associated with flourishing? Results from a large representative national sample. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 1351–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruyter, D.J. Pottering in the garden? On human flourishing and education. Br. J. Educ. 2004, 52, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-F.; Chang, Y.P.; Lin, C.; Yen, C.F. Quality of life of gay and bisexual men during emerging adulthood in Taiwan: Roles of traditional and cyber harassment victimization. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collen, H.O.; Onan, N. Cyberbullying and well-being among university students: The role of resilience. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 14, 632–641. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Bowes, L. Cyberbullying and adolescent well-being in England: A population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet Child Adolesc. 2017, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Molina, B.; Perez-Albeniz, A.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. The potential role of subjective wellbeing and gender in the relationship between bullying or cyberbullying and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, A.L.; Rider, G.N.; McMorris, B.J.; Eisenberg, M.E. Bullying victimization among LGBTQ youth: Critical issues and future directions. Curr. Sex Health Rep. 2018, 10, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynes, B.; Schuschke, J.; Noble, S.U. Digital intersectionality theory and the #BlackLivesMatter movement. In The Intersectional Internet: Race, Sex, Class, and Culture Online; Noble, S.U., Tynes, B.M., Eds.; Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sue, D.W.; Sue, D.; Neville, H.A.; Smith, L. Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice, 9th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Cyberbullying Fact Sheet: Cyberbullying and Sexual Orientation. 2011. Available online: https://cyberbullying.org/cyberbullying_sexual_orientation_fact_sheet.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Bullying, Cyberbullying, and LGBTQ Students. 2020. Available online: https://cyberbullying.org/bullying-cyberbullying-sexual-orientation-lgbtq.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Romano, I.; Butler, A.; Patte, K.A.; Ferro, M.A.; Leatherdale, S.T. High school bullying and mental disorder: An examination of the association with flourishing and emotional regulation. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2020, 2, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taragua, A.T.R. Issues and concerns of the academic wellbeing of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgenders: A qualitative study. Globus J. Prog. Educ. 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, L.; Mérida-López, S.; Sánchez-Álvarez, N.; Extremera, N. When and how do emotional intelligence and flourishing protect against suicide risk in adolescent bullying victims? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.S.W.; Wu, D.; Lo, I.P.Y.; Ho, J.M.C.; Yan, E. Diversity and inclusion: Impacts on psychological wellbeing among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer communities. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 726343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, C. What is hidden can still hurt: Concealable stigma, psychological well-being, and social support among LGB college students. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 18, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyeres, M.; Carter, M.-A.; Lui, S.M.; Low-Lim, Ä.; Teo, S.; Tsey, K. Cyberbullying prevention and treatment interventions targeting young people: An umbrella review. Pastor. Care Educ. 2021, 39, 125–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker Darrow, N.E.; Duran, A.; Weise, J.A.; Guffin, J.P. LGBTQ+ college students’ mental health: A content analysis of research published 2009–2019. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. 2022; 1–30, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggle, E.D.B.; Gonzalez, K.A.; Rostosky, S.S.; Black, W.W. Cultivating positive LGBTQA identities: An intervention study with college students. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 2014, 8, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K.W. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. In Foundations of Critical Race Theory in Education, 3rd ed.; Taylor, E., Gillborn, D., Ladson-Billings, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 273–307. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, T.; Taylor, C. Buried above ground: A university-based study of risk/protective factors for suicidality among sexual minority youth in Canada. J. LGBT Youth 2014, 11, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, M.R.; Weber, G.; Nicolazzo, Z.; Hunt, R.; Kulick, A.; Coleman, T.; Coulombe, S.; Renn, K.A. Depression and attempted suicide among LGBTQ college students: Fostering resilience to the effects of heterosexism and cisgenderism on campus. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2018, 59, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lira, A.N.; de Morais, N.A. Resilience in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) populations: An integrative literature review. Sex Res. Soc. Pol. 2018, 15, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Academic satisfaction | 29.27 (8.13) | - | |||

| 2. Cyberbullying victimization | 9.31 (1.35) | −0.12 | - | ||

| 3. Flourishing | 40.08 (9.60) | 0.46 ** | −0.23 ** | - | |

| 4. Age | 22.52 (4.83) | 0.16 * | 0.00 | 0.01 | - |

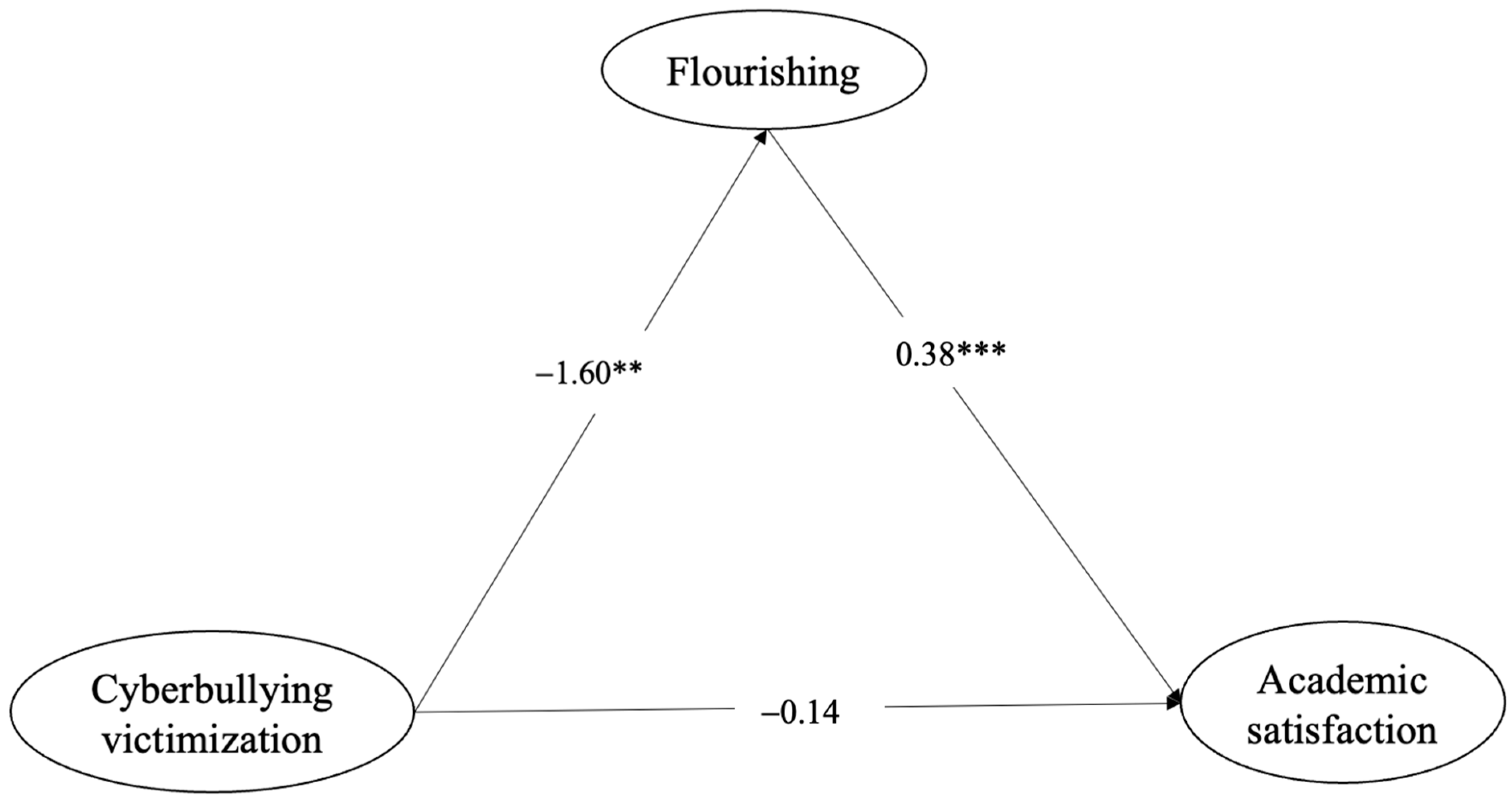

| Predictor (X) | Mediator (M) | Outcome (Y) | Effect of X on M (a) | Effect of M on Y Controlled by X (b) | Total Effect C | Direct Effect C′ | Indirect Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a × b | 95% Bca CI | |||||||

| Cyberbullying victimization | Flourishing | Academic satisfaction | −1.60 ** | 0.38 *** | −0.75 | −0.14 | −0.61 | −1.20 −0.06 |

| covariance | Age | 0.26 * | 0.27 * | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.M.; Park, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Mallonee, J. The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Academic Satisfaction among Sexual Minority College Students: The Indirect Effect of Flourishing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6248. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136248

Lee JM, Park J, Lee H, Lee J, Mallonee J. The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Academic Satisfaction among Sexual Minority College Students: The Indirect Effect of Flourishing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(13):6248. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136248

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jeoung Min, Jinhee Park, Heekyung Lee, Jaegoo Lee, and Jason Mallonee. 2023. "The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Academic Satisfaction among Sexual Minority College Students: The Indirect Effect of Flourishing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 13: 6248. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136248

APA StyleLee, J. M., Park, J., Lee, H., Lee, J., & Mallonee, J. (2023). The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Academic Satisfaction among Sexual Minority College Students: The Indirect Effect of Flourishing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(13), 6248. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20136248