Eudaimonic Well-Being of Italian Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Predictive and Mediating Roles of Fear of Death and Psychological Inflexibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic

1.2. Italian Young Adults’ Psychological Well-Being during the Pandemic

1.3. Fear of Death, Psychological Inflexibility, and Eudaimonic Psychological Well-Being during the Pandemic

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Eudaimonic Well-Being

2.3.2. Psychological Inflexibility

2.3.3. Fear of Death

2.4. Data Analyses

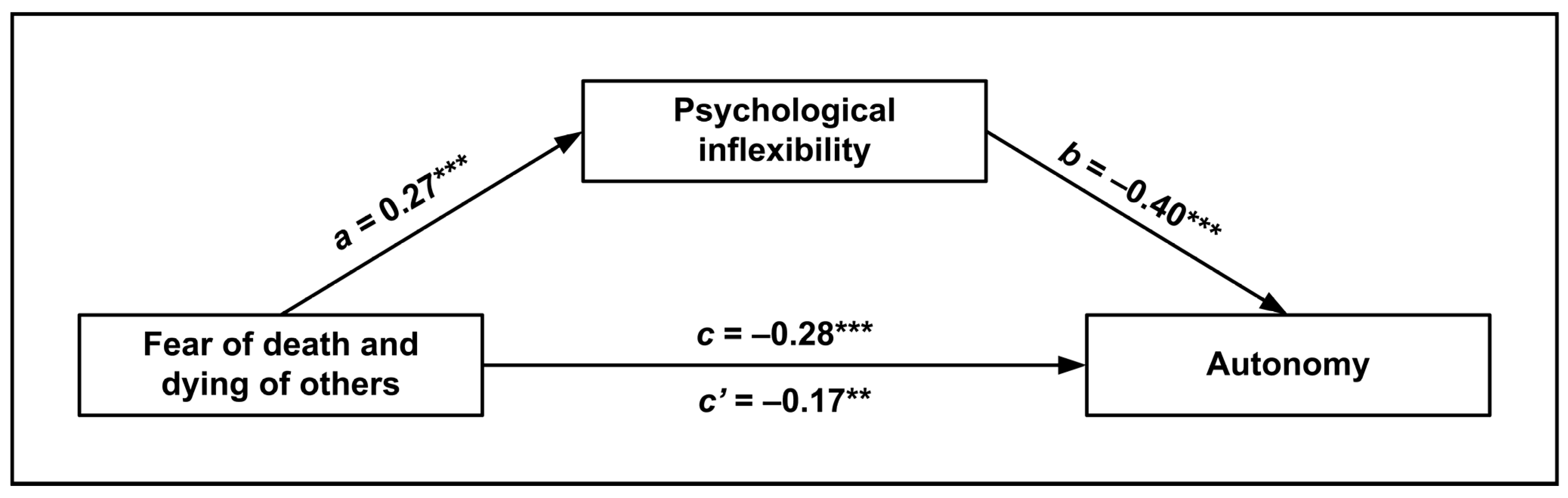

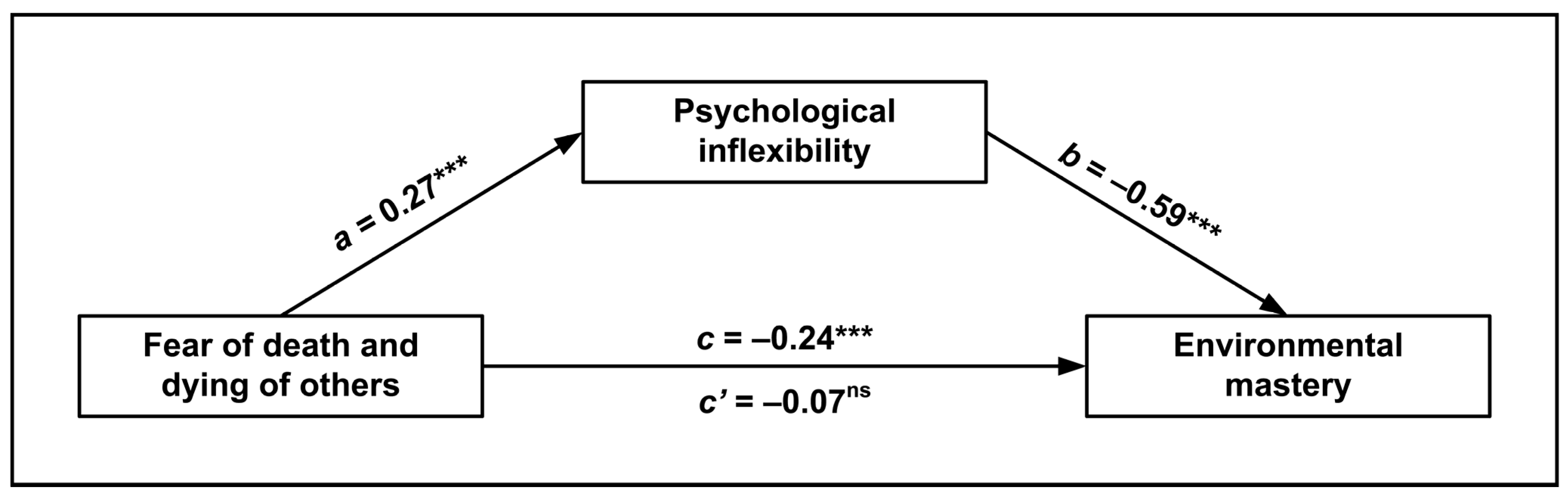

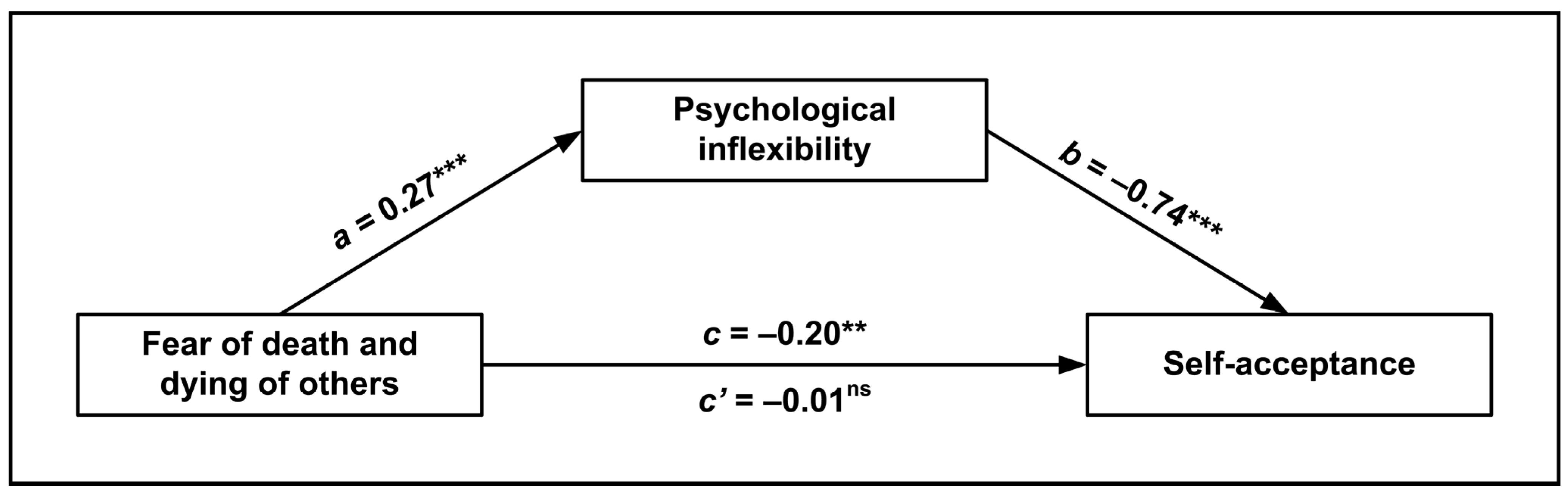

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anglim, J.; Horwood, S. Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Big Five Personality on Subjective and Psychological Well-Being. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2021, 12, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, C.; McGlinchey, E.; Butter, S.; McAloney-Kocaman, K.; McPherson, K.E. The COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study: Understanding the Longitudinal Psychosocial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK; a Methodological Overview Paper. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2021, 43, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villani, L.; Pastorino, R.; Molinari, E.; Anelli, F.; Ricciardi, W.; Graffigna, G.; Boccia, S. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Psychological Well-Being of Students in an Italian University: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favieri, F.; Forte, G.; Tambelli, R.; Casagrande, M. The Italians in the Time of Coronavirus: Psychosocial Aspects of the Unexpected COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 551924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, L.; Steinhoff, A.; Bechtiger, L.; Murray, A.L.; Nivette, A.; Hepp, U.; Ribeaud, D.; Eisner, M. Emotional Distress in Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence of Risk and Resilience from a Longitudinal Cohort Study. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, M.T.; Szenczy, A.K.; Klein, D.N.; Hajcak, G.; Nelson, B.D. Increases in Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents and Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3222–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Wetherall, K.; Cleare, S.; McClelland, H.; Melson, A.J.; Niedzwiedz, C.L.; O’Carroll, R.E.; O’Connor, D.B.; Platt, S.; Scowcroft, E.; et al. Mental Health and Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Analyses of Adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing Study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 218, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Cadigan, J.M.; Rhew, I.C. Increases in Loneliness Among Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Association with Increases in Mental Health Problems. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Socci, V.; Talevi, D.; Mensi, S.; Niolu, C.; Pacitti, F.; Di Marco, A.; Rossi, A.; Siracusano, A.; Di Lorenzo, G. COVID-19 Pandemic and Lockdown Measures Impact on Mental Health Among the General Population in Italy. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąsowicz, G.; Mizak, S.; Krawiec, J.; Białaszek, W. Mental Health, Well-Being, and Psychological Flexibility in the Stressful Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, I.; Gutman, L.M. Longitudinal Changes in the Mental Health of UK Young Male and Female Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 303, 114074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czenczek-Lewandowska, E.; Wyszyńska, J.; Leszczak, J.; Baran, J.; Weres, A.; Mazur, A.; Lewandowski, B. Health Behaviours of Young Adults during the Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Longitudinal Study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Zueco, J.; Díaz, A.; del Pino, M.J.; Fortes, D. Gender Differences in Mental Distress and Affect Balance during the First Wave of COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 12, 551924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J.; Prinstein, M.J.; Clark, L.A.; Rottenberg, J.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Albano, A.M.; Aldao, A.; Borelli, J.L.; Chung, T.; Davila, J.; et al. Mental Health and Clinical Psychological Science in the Time of COVID-19: Challenges, Opportunities, and a Call to Action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetta, G.; Campolo, M.G.; Panarello, D. Economic Expectations and Anxiety during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A One-Year Longitudinal Evaluation on Italian University Students. Qual. Quant. 2022, 57, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, R.; Averna, A.; Marino, D.; Reitano, M.R.; Ruggiero, F.; Mameli, F.; Dini, M.; Poletti, B.; Barbieri, S.; Priori, A.; et al. Psychological Impact during the First Outbreak of COVID-19 in Italy. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 559266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Girolamo, G.; Ferrari, C.; Candini, V.; Buizza, C.; Calamandrei, G.; Caserotti, M.; Gavaruzzi, T.; Girardi, P.; Habersaat, K.B.; Lotto, L.; et al. Psychological Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy Assessed in a Four-Waves Survey. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini Usubini, A.; Cattivelli, R.; Varallo, G.; Castelnuovo, G.; Molinari, E.; Giusti, E.M.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manari, T.; Filosa, M.; Franceschini, C.; et al. The Relationship between Psychological Distress during the Second Wave Lockdown of COVID-19 and Emotional Eating in Italian Young Adults: The Mediating Role of Emotional Dysregulation. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, M.; Carlucci, L. Italians on the Age of COVID-19: The Self-Reported Depressive Symptoms Through Web-Based Survey. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 569276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, S.; Di Tata, D.; Bianchi, D.; Lonigro, A.; Zammuto, M.; Baiocco, R.; Longobardi, E.; Laghi, F. Food and Alcohol Disturbance among Young Adults during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: Risk and Protective Factors. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, A.; Rossi, A.; Tessitore, F.; Troisi, G.; Mannarini, S. Mental Health Through the COVID-19 Quarantine: A Growth Curve Analysis on Italian Young Adults. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Colasanti, M.; Ferracuti, S.; Napoli, C.; Roma, P. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetto, L.; Vicentino, C.; Merulla, C.; Ingrassia, M. Perduring COVID-19 Pandemic, Perceived Well-Being, and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Behaviors (NSSI) in Emerging Adults. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, L.; Pesce, A.; Guazzini, A. Before and after the Quarantine: An Approximate Study on the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on the Italian Population during the Lockdown Period. Future Internet 2020, 12, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleari, F.G.; Pivetti, M.; Galati, D.; Fincham, F.D. Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: The Role of Stigma and Appraisals. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 657–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, V.; D’Aquila, C.; Rocco, D.; Carraro, E. Attachment and Well-Being: Mediatory Roles of Mindfulness, Psychological Inflexibility, and Resilience. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 2966–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, M.; Schilling, O.K.; Wahl, H.-W. Trajectories of Pain in Very Old Age: The Role of Eudaimonic Wellbeing and Personality. Front. Pain. Res. 2022, 3, 807179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological Well-Being Revisited: Advances in the Science and Practice of Eudaimonia. Psychother. Psychosom. 2014, 83, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, R.E.; Menzies, R.G. Death Anxiety in the Time of COVID-19: Theoretical Explanations and Clinical Implications. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2020, 13, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.; Pyszczynski, T.; Solomon, S. The Causes and Consequences of a Need for Self-Esteem: A Terror Management Theory. In Public Self and Private Self; Baumeister, R.F., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 189–212. ISBN 978-1-4613-9566-9. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, S.; Greenberg, J.; Pyszczynski, T. A Terror Management Theory of Social Behavior: The Psychological Functions of Self-Esteem and Cultural Worldviews. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; Volume 24, pp. 93–159. ISBN 978-0-12-015224-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski, T.; Lockett, M.; Greenberg, J.; Solomon, S. Terror Management Theory and the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2021, 61, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.A.D.; de Sampaio Brito, T.R.; Pereira, C.R. Anxiety Associated with COVID-19 and Concerns about Death: Impacts on Psychological Well-Being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 176, 110772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curșeu, P.L.; Coman, A.D.; Panchenko, A.; Fodor, O.C.; Rațiu, L. Death Anxiety, Death Reflection and Interpersonal Communication as Predictors of Social Distance towards People Infected with COVID-19. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 1490–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.; Ashraf, F.; Muazzam, A.; Amjad, M.; Javed, S. Work Status, Death Anxiety and Psychological Distress during COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications of the Terror Management Theory. Death Stud. 2021, 44, 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundogan, S.; Arpaci, I. Depression as a Mediator between Fear of COVID-19 and Death Anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Mengual, N.; Aragonés-Barbera, I.; Moret-Tatay, C.; Moliner-Albero, A.R. The Relationship of Fear of Death between Neuroticism and Anxiety during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 648498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y. Examining the Relationship between Death Anxiety and Well-Being of Frontline Medical Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, E.P.; Tasso, A. Are You Willing to Protect the Health of Older People? Intergenerational Contact and Ageism as Predictors of Attitudes toward the COVID-19 Vaccination Passport. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søraa, R.A.; Manzi, F.; Kharas, M.W.; Marchetti, A.; Massaro, D.; Riva, G.; Serrano, J.A. Othering and Deprioritizing Older Adults’ Lives: Ageist Discourses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaccatini, F.; Giovannelli, I.; Pacilli, M.G. “You Are Stealing Our Present”: Younger People’s Ageism towards Older People Predicts Attitude towards Age-based COVID-19 Restriction Measures. J. Soc. Issues 2022, 78, 769–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjölander-Lindqvist, A.; Larsson, S.; Fava, N.; Gillberg, N.; Marcianò, C.; Cinque, S. Communicating About COVID-19 in Four European Countries: Similarities and Differences in National Discourses in Germany, Italy, Spain, and Sweden. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 593325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crasta, D.; Daks, J.S.; Rogge, R.D. Modeling Suicide Risk among Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Psychological Inflexibility Exacerbates the Impact of COVID-19 Stressors on Interpersonal Risk Factors for Suicide. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 18, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, Processes and Outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillanders, D.T.; Bolderston, H.; Bond, F.W.; Dempster, M.; Flaxman, P.E.; Campbell, L.; Kerr, S.; Tansey, L.; Noel, P.; Ferenbach, C.; et al. The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire. Behav. Ther. 2014, 45, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Xu, X.; Chan, K.L.; Chen, S.; Assink, M.; Gao, S. Associations between Psychological Inflexibility and Mental Health Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Three-Level Meta-Analytic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 320, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, A.J.; Demuynck, K.M. Psychological Flexibility and Psychological Inflexibility Are Independently Associated with Both Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 20, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, K.; Sen, I.; Gupta, P.; Parekh, S. Psychological Well-Being of Indian Mothers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. Perspect. Psychol. 2021, 10, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Yıldırım, M.; Tanhan, A.; Buluş, M.; Allen, K.-A. Coronavirus Stress, Optimism-Pessimism, Psychological Inflexibility, and Psychological Health: Psychometric Properties of the Coronavirus Stress Measure. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 2423–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avsec, A.; Eisenbeck, N.; Carreno, D.F.; Kocjan, G.Z.; Kavčič, T. Coping Styles Mediate the Association between Psychological Inflexibility and Psychological Functioning during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Crucial Role of Meaning-Centered Coping. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 26, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla-Sierra, P.; Manrique-G, A.; Hidalgo-Andrade, P.; Ruisoto, P. Psychological Inflexibility and Loneliness Mediate the Impact of Stress on Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Healthcare Students and Early-Career Professionals during COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 729171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marogna, C.; Masaro, C.; Calvo, V.; Ghedin, S.; Caccamo, F. The Extended Unconscious Group Field and Metabolization of Pandemic Experience: Dreaming Together to Keep Cohesion Alive. Res. Psychother. Psychopathol. Process Outcome 2022, 25, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, B.L.; Zanin, A.C.; Avalos, B.L.; Tracy, S.J.; Town, S. Collective Emotion during Collective Trauma: A Metaphor Analysis of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 1890–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Fuente, J. Theory of Self- vs. Externally-Regulated LearningTM: Fundamentals, Evidence, and Applicability. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Fuente, J.; Pachón-Basallo, M.; Martínez-Vicente, J.M.; Peralta-Sánchez, F.J.; Garzón-Umerenkova, A.; Sander, P. Self- vs. External-Regulation Behavior ScaleTM in Different Psychological Contexts: A Validation Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 922633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leerkes, E.M.; Su, J.; Sommers, S.A. Mothers’ Self-Reported Emotion Dysregulation: A Potentially Valid Method in the Field of Infant Mental Health. Infant Ment. Health J. 2020, 41, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, Ö.; Özkan, O.; Özmen, S.; Erçoban, N. Investigation of the Effect of COVID-19 Perceived Risk on Death Anxiety, Satisfaction with Life, and Psychological Well-Being. Omega 2021, 00302228211026169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruini, C.; Ottolini, F.; Rafanelli, C.; Ryff, C.D.; Fava, G.A. La validazione italiana delle Psychological Well-being Scales (PWB) [Italian validation of the Psychological Well-being Scales (PWB)]. Riv. Psichiatr. 2003, 38, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirigatti, S.; Stefanile, C.; Giannetti, E.; Iani, L.; Penzo, I.; Mazzeschi, A. Assessment of Factor Structure of Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scales in Italian Adolescents. Boll. Psicol. Appl. 2009, 259, 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pennato, T.; Berrocal, C.; Bernini, O.; Rivas, T. Italian Version of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II): Dimensionality, Reliability, Convergent and Criterion Validity. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2013, 35, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, D.; Abdel-Khalek, A. The Collett-Lester Fear of Death Scale: A Correction. Death Stud. 2003, 27, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Ronconi, L.; Cupit, I.N.; Nodari, E.; Bormolini, G.; Ghinassi, A.; Messeri, D.; Cordioli, C.; Zamperini, A. The Effect of Death Education on Fear of Death amongst Italian Adolescents: A Nonrandomized Controlled Study. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFebvre, A.; Huta, V. Age and Gender Differences in Eudaimonic, Hedonic, and Extrinsic Motivations. J. Happiness Stud. Interdiscip. Forum Subj. Well-Being 2021, 22, 2299–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanomi, A.; Rosina, A. Employment Status and Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study on Young Italian People. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 161, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Methodology in the Social Sciences; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4625-3465-4. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-8058-0283-2. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, M.S.; MacKinnon, D.P. Required Sample Size to Detect the Mediated Effect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Eudaimonic Well-Being, Inequality, and Health: Recent Findings and Future Directions. Int. Rev. Econ. 2017, 64, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, F.R.; Larrazabal, M.A.; West, J.T.; Kashdan, T.B. Experiential Avoidance. In The Cambridge Handbook of Anxiety and Related Disorders; Olatunji, B.O., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 255–281. ISBN 978-1-108-14041-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-60918-962-4. [Google Scholar]

- McClatchey, I.S.; King, S. The Impact of Death Education on Fear of Death and Death Anxiety among Human Services Students. Omega 2015, 71, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.R.; Swets, J.A.; Gully, B.; Xiao, J.; Yraguen, M. Death Concerns, Benefit-Finding, and Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okechukwu, G.-P.; Nnam, M.U.; Obadimu, C.E.; Iloma, D.O.; Offu, P.; Okpata, F.; Nwakanma, E.U. COVID-19 Lockdown Related Stress among Young Adults: The Role of Drug Use Disorder, Neurotic Health Symptoms, and Pathological Smartphone Use. J. Forensic Psychol. Res. Pract. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montpetit, M.A.; Tiberio, S.S. Probing Resilience: Daily Environmental Mastery, Self-Esteem, and Stress Appraisal. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2016, 83, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Stirnberg, J.; Rozgonjuk, D.; Margraf, J.; Elhai, J.D. From Low Sense of Control to Problematic Smartphone Use Severity during COVID-19 Outbreak: The Mediating Role of Fear of Missing out and the Moderating Role of Repetitive Negative Thinking. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Panzeri, A.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Castelnuovo, G.; Mannarini, S. The Anxiety-Buffer Hypothesis in the Time of COVID-19: When Self-Esteem Protects From the Impact of Loneliness and Fear on Anxiety and Depression. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Barrios, V.; Forsyth, J.P.; Steger, M.F. Experiential Avoidance as a Generalized Psychological Vulnerability: Comparisons with Coping and Emotion Regulation Strategies. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1301–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Gifford, E.V. The Trouble with Language: Experiential Avoidance, Rules, and the Nature of Verbal Events. Psychol. Sci. 1997, 8, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, D.M. When the Antidote Is the Poison: Ironic Mental Control Processes. Psychol. Sci. 1997, 8, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yang, R.; Cheng, Q.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X. Factors Influencing Death Anxiety among Chinese Patients with Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Orsillo, S.M.; Roemer, L.; Allen, L.B. Distress and Avoidance in Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Exploring the Relationships with Intolerance of Uncertainty and Worry. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2010, 39, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. The Limitations of Online Surveys. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, A.C.J.W.; Kraft, P. Research Conducted Using Data Obtained through Online Communities: Ethical Implications of Methodological Limitations. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiori, F.; Rinesi, F.; Spizzichino, D.; Di Giorgio, G. Employment Insecurity and Mental Health during the Economic Recession: An Analysis of the Young Adult Labour Force in Italy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 153, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piumatti, G.; Pipitone, L.; Di Vita, A.M.; Latina, D.; Rabaglietti, E. Transition to Adulthood Across Italy: A Comparison between Northern and Southern Italian Young Adults. J. Adult Dev. 2014, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: What Is It, and What Is It Good for? Child Dev. Perspect. 2007, 1, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgüç, S.; Kaplan Serin, E.; Tanriverdi, D. Death Anxiety Associated with Coronavirus (COVID-19) Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Omega 2021, 003022282110505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, C.; Masaro, C.; Calvo, V. ‘I Feel like I Was Born for Something That My Body Can’t Do’: A Qualitative Study on Women’s Bodies within Medicalized Infertility in Italy. Psychol. Health 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, V.; Bianco, F.; Benelli, E.; Sambin, M.; Monsurrò, M.R.; Femiano, C.; Querin, G.; Sorarù, G.; Palmieri, A. Impact on Children of a Parent with ALS: A Case-Control Study. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Palazzo, L.; Ronconi, L.; Macelloni, T.; Calvo, V. Strengths and Weaknesses of Children Witnessing Relatives with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Children 2023, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; Palazzo, L.; Pamini, S.; Ferizoviku, J.; Boros, A.; Calvo, V. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Impact on Minors’ Life: A Qualitative Study with Children of ALS Patients in Italy. J. Loss Trauma 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, V.; Palmieri, A.; Codamo, A.; Scampoli, M.R.; Bianco, F. Perceptions of Parental Bonding, Adult Attachment, and Marital Adjustment in Prospective Adoptive Parents. An Empirical Study in the Pre-Adoptive Period. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2015, 30, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccardo, C.; Calvo, V. Relational Sequelae of Fetal Death during the First Pregnancy: A Qualitative Study on the Subjective Perceptions of the Relationship between Mothers and Their Adult Subsequent Firstborn Children. Omega 2020, 85, 604–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, V.; Masaro, C.; Fusco, C. Attachment and emotion regulation across the life cycle [Attaccamento e regolazione emozionale nel ciclo di vita]. G. Ital. Psicol. 2021, 48, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, I.; Calvo, V.; Masaro, C.; Ghedin, S.; Marogna, C. Interpersonal Emotion Regulation: From Research to Group Therapy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 636919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindman, R.K.; Glass, C.R.; Arnkoff, D.B.; Maron, D.D. A Comparison of Formal and Informal Mindfulness Programs for Stress Reduction in University Students. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.M.; Ong, C.W.; Barrett, T.S.; Bluett, E.J.; Slocum, T.A.; Twohig, M.P. Longitudinal Effects of a 2-Year Meditation and Buddhism Program on Well-Being, Quality of Life, and Valued Living. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 2095–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloster, A.T.; Meyer, A.H.; Lieb, R. Psychological Flexibility as a Malleable Public Health Target: Evidence from a Representative Sample. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2017, 6, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Parolin, L.; Calvo, V.; Zennaro, A.; Meyer, G. The Impact of Administration and Inquiry on Rorschach Comprehensive System Protocols in a National Reference Sample. J. Personal. Assess. 2007, 89, S193–S200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, S.; Rickwood, D. Psychosocial Assessments for Young People: A Systematic Review Examining Acceptability, Disclosure and Engagement, and Predictive Utility. AHMT 2012, 3, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Measure | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Autonomy (PWB) | 38.34 | 8.23 | – | 0.40 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.40 ** | −0.42 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.26 ** |

| 2. Environmental mastery (PWB) | 35.03 | 9.31 | – | 0.54 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.75 ** | −0.65 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.25 ** | |

| 3. Personal growth (PWB) | 46.10 | 6.34 | – | 0.39 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.63 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.07 | −0.05 | ||

| 4. Positive relations with others (PWB) | 38.91 | 9.97 | – | 0.38 ** | 0.50 ** | −0.47 ** | 0.03 | −0.05 | |||

| 5. Purpose in life (PWB) | 36.97 | 9.43 | – | 0.72 ** | −0.62 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.20 ** | ||||

| 6. Self-acceptance (PWB) | 36.23 | 9.11 | – | −0.74 ** | −0.13 * | −0.19 ** | |||||

| 7. Psychological inflexibility (AAQ-II) | 23.47 | 10.14 | – | 0.26 ** | 0.30 ** | ||||||

| 8. Fear of death and dying of self (CL-FODS) | 43.64 | 12.52 | – | 0.57 ** | |||||||

| 9. Fear of death and dying of others (CL-FODS) | 53.14 | 9.84 | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calvo, V.; Masaro, C.; Fusco, C.; Pellicelli, C.; Ghedin, S.; Marogna, C. Eudaimonic Well-Being of Italian Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Predictive and Mediating Roles of Fear of Death and Psychological Inflexibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115960

Calvo V, Masaro C, Fusco C, Pellicelli C, Ghedin S, Marogna C. Eudaimonic Well-Being of Italian Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Predictive and Mediating Roles of Fear of Death and Psychological Inflexibility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115960

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalvo, Vincenzo, Chiara Masaro, Chiara Fusco, Camilla Pellicelli, Simona Ghedin, and Cristina Marogna. 2023. "Eudaimonic Well-Being of Italian Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Predictive and Mediating Roles of Fear of Death and Psychological Inflexibility" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115960

APA StyleCalvo, V., Masaro, C., Fusco, C., Pellicelli, C., Ghedin, S., & Marogna, C. (2023). Eudaimonic Well-Being of Italian Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Predictive and Mediating Roles of Fear of Death and Psychological Inflexibility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5960. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115960