Exploration of Existing Integrated Mental Health and Addictions Care Services for Indigenous Peoples in Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Questions

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Sample

2.2. Design and Procedure

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Data

3.2. Lessons from Existing Integrated Care Programs

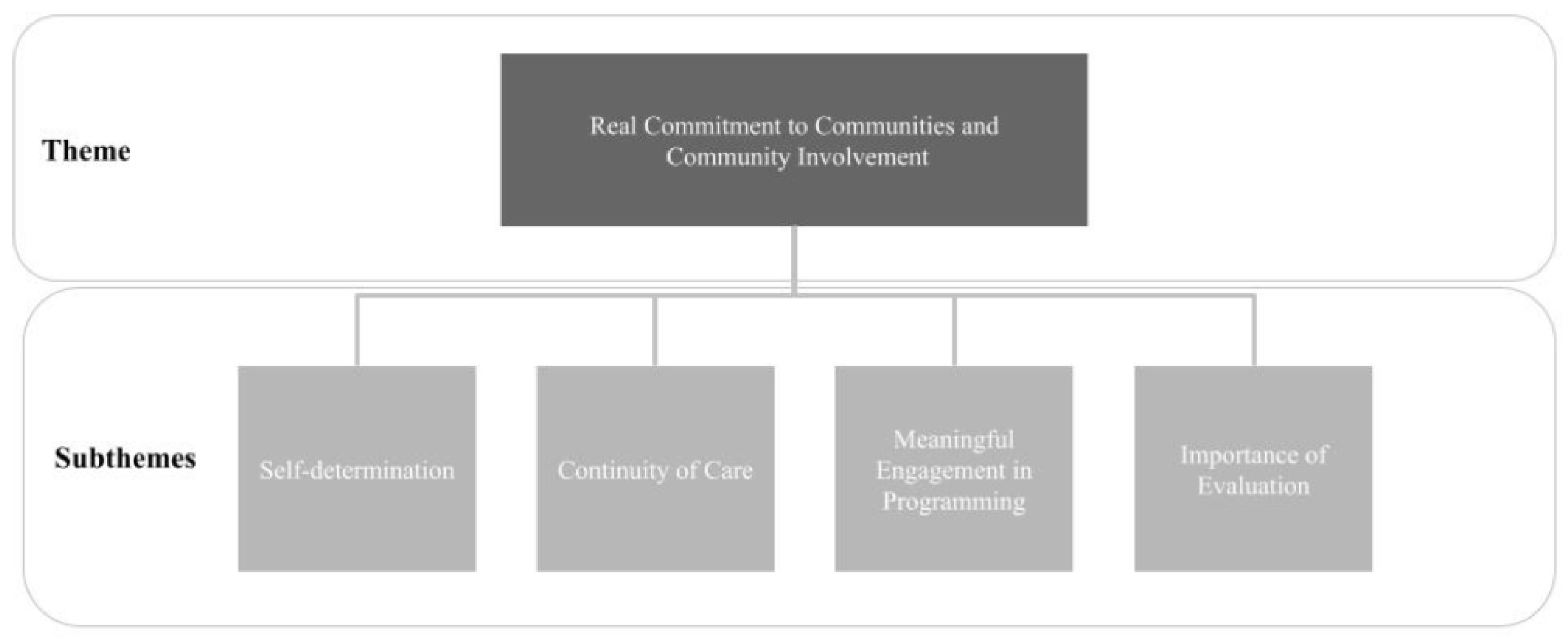

Real Commitment to Communities and Community Involvement

“[Our treatment centre] began in 1976—four First Nations people from X and Y communities met to discuss alcohol problems of our people. They felt that the single biggest problem was the lack of alcohol and drug treatment centres. They organized, developed a proposal and lobbied for funding.”(A4).

“I think one thing that a lot of treatment centres work towards is aftercare. […] Before we’d hear [from clients in therapy], “I don’t want to go back home, I’m not comfortable at home. I’m not comfortable to go back into that environment. […] But it would be nice to have more programs that would take clients coming right from treatment. And maybe they’ll see them for two months and maybe, you know, help them get back onto the job, and help them establish healthy [habits] or move back to school.”(A8).

“We have a Board of Directors, sometimes I would say—and everyone who’s on our board is in sobriety; some of them have been on a long time, a lot of them are what you would consider Elders.”(A5).

“I am the Treatment Director […] I’m a former client of the [counselling centre]. Back in 2009, they were a reconciliation program because of the Indian Day Schools, the Residential Schools. So I went through the program […] I do like using my story because clients will ask me ‘how did you do it?”(A7).

“We’ve gotten feedback from clients, staff, and referral agents, from court, personal liaisons […] So we’ve really gathered a lot of feedback over the last few years to see if what we’re doing is working and where our needs are. As time has moved on, so have the needs of the individual.”(A1).

3.3. Tensions and Disjunctures within Integrated Care

3.3.1. Culture as Healing

“We are a First Nations treatment Centre serving mostly First Nations people and are grounded in the First Nation’s cultural values of respect and honour for all living things.”(A4).

“But we quickly found out that there was something under all of this [alcoholism and addictions], which is from unresolved trauma and colonization, and not feeling good enough and not feeling like they belong because of the disconnection that happened due to the residential schools and scooping our children and taking away our ceremony and banning our languages and keeping us little tiny plots of land, and not letting us live with the land and function in a way that we normally do.”(A5).

“We find that with the [cultural programming], people can adapt to it more—they understand it better. Because they’re able to connect with it, especially if it’s an Elder talking about parenting and stuff like that. They’re going to adapt to it more if an Elder is speaking rather than someone coming and giving a workshop. That kind of thing. [With the Elders], there’s a lot more respect as well.”(A8).

“Some communities have even banned some of the cultural ceremonies and practices which were traditionally part of their territory. When individuals from those communities that have banned or outlawed these types of ceremony come to the centre, I notice that they’re really hesitant.”(A1).

“So we try to incorporate our language into some of the programs; it’s really hard because some of [the clients] have a ‘mental block’ into trying to speak our language again. I think in some ways, it has to do with colonization and in some ways, some of the people have almost lost our native tongue, and it’s hard to pronounce the sounds properly.”(A6).

“One of the programs that we’ve recently introduced in these past few years is the Circle of Security Parenting Program, but we’ve adapted it to [the community’s] values…”(A2).

“And we’d also have cultural aspects of First Nations: sharing circles, healing circles.”(A9).

“So part of the program we have is that we integrate an “on the land” component by arranging for a retreat outside of [the city]. We use an [equestrian retreat] and we integrate equestrian therapy as well as camping, fire, hikes, those sorts of things to try and mimic what our connection to the land or ‘on the land’ learning would look like in an urban context.”(A3).

3.3.2. People-Focused vs. Practitioner-Focused Programs

“[Clients] have the choice to choose the change.” And if they don’t want to change, then they’re stuck. If they make that change, they’ll give themselves wings and look at themselves as birds on a wire.”(A7).

“One of the things people always ask me is ‘how successful is your program?’ and I say ‘tell me what you call success? How are you measuring success?’ I think if someone’s life has improved from walking through our doors, whether they stay an hour, a day, a week or complete our program, if something has improved in their life, then I think for them its successful.”(A5).

3.3.3. Community-Oriented vs. Individual-Oriented Programs

“We developed this whole program based on treating the whole family; it was never just like take the one person that’s drinking, it was like the whole family was looked at in needing support and help.”(A2).

“We also provide a Colleagues Program for individuals who work with First Nations […] Its focus is addressing the effects of intergenerational trauma and the impact of unresolved trauma and shame on our people.”(A4).

3.3.4. Colonial Power Dynamics in Integrated Care

“The person going through treatment maybe got a low educational level, and the language […] It’s like that can be a barrier where… How do you sort of address that if the understanding is not there?”(A9).

“How do you make [topics like neuroscience] understandable and translate it to people who are just making it day-to-day, people who have been using substances… How do you make them really get it?”(A2).

“A lot of the psychologists and psychiatrists and social workers for that matter don’t understand what happened to us! […] And so then they try to impose their views like there’s something flawed about us.”(A2).

“Right now, something that I’m actively working on is creating a guidance system for our staff, our clients, our partners on Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (Inuit Knowledge). […] And I think it’s especially important if you’re in an organization where 100% of staff are not Indigenous.”(A3).

“You know what, I’m always teaching. Especially in circles where there’s settlers. The reason I do that is because sometimes it’s just ignorance and they don’t have a clue […] I truly believe that our people know how to heal.”(A5).

“Always working from a budgetary approach—the way the government does—really does limit us. There’s always more things that we want to do moving forward, there are a lot of great ideas that we have as a team, but we are always limited in terms of dollars.”(A1).

“[The healing centre] operated for a few years, and then we lost funding […] the program completely had to shut down, and it was very very difficult for the community to go through that. It was traumatic to both staff that were working at the healing centre and clients.”(A3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Placing Our Study Findings in Theory and History: Why Do These Tensions and Disjunctures Exist?

4.2. What Is Next? Drawing on Integrated Care’s Lessons to Move towards IND-Equity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Indigenous Land Defenders Shut Down Major Intersection and Port Access in Vancouver. Available online: https://bc.ctvnews.ca/indigenous-land-defenders-shut-down-major-intersection-and-port-access-in-vancouver-1.5201464 (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; Library and Archives: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, C.; Feeny, D.; Tompa, E. Canada’s residential school system: Measuring the intergenerational impact of familial attendance on health and mental health outcomes. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanoski, K.A. Need for equity in treatment of substance use among Indigenous people in Canada. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2017, 189, E1350–E1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, C.A.M.; Cook, C. Creating conditions for Canadian aboriginal health equity: The promise of healthy public policy. Public Health Rev. 2016, 37, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smye, V.; Browne, A.J.; Varcoe, C.; Josewki, V. Harm reduction, methadone maintenance treatment and the root causes of health and social inequities: An intersectional lens in the Canadian context. Harm Reduct. J. 2011, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challenging Hidden Assumptions: Colonial Norms as Determinants of Aboriginal Mental Health. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. Available online: https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/determinants/FS-ColonialNorms-Nelson-EN.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Richmond, C.A.M.; Ross, N.A.; Bernier, J. Exploring Indigenous Concepts of Health: The Dimensions of Métis and Inuit Health. Aborig. Policy Res. Vol. IV Setting Agenda Change 2007, 4, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Smye, V.L. The Nature of the Tensions and Disjunctures Between Aboriginal Understandings of and Responses to Mental Health and Illness and the Current Mental Health System. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, K.; Passmore, A.; Kellock, T.; Nevin, J. Understanding Integrated Care: The Aboriginal Health Initiative Heads North. Univ. Br. Columbia Med. J. 2011, 3, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, C.; Marshall, M.; Marshall, A. Two-Eyed Seeing and other Lessons Learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2012, 2, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.; Hatala, A.; Ijaz, S.; Hon, D.C.; Bushie, B. Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, E.; Jones, R.; Tipene-Leach, D.; Walker, C.; Loring, B.; Paine, S.-J.; Reid, P. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brascoupé, S.; Waters, C. Cultural Safety: Exploring the Applicability of the Concept of Cultural Safety to Aboriginal Health and Community Wellness. Int. J. Indig. Health 2009, 5, 6–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, C.; Branch, C. What is Indigenous Cultural Safety—And Why Should I Care About It? Vis. J. 2016, 11, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous, First Nations, Inuit and Métis (FNIM). Available online: https://www.ementalhealth.ca/Toronto/Indigenous-First-Nations-Inuit-and-Metis-FNIM/index.php?m=heading&ID=124 (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Substance Use Treatment Centres for First Nations and Inuit; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada. Available online: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1576090254932/1576090371511 (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Aboriginal Health Access Centres. Alliance for Healthier Communities. Available online: https://www.allianceon.org/aboriginal-health-access-centres (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Kovach, M. Conversational Method in Indigenous Research. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2010, 5, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. What Is an Indigenous Research Methodology? Can. J. Nativ. Educ. 2001, 25, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples; Zed Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kincheloe, J.L.; Mclaren, P. Rethinking Critical Theory and Qualitative Research. In Key Works in Critical Pedagogy; Hayes, K., Steinberg, S.R., Tobin, K., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 285–326. [Google Scholar]

- John, L. With your foodbasket and my foodbasket, the visitors will be well: Combining Postcolonial and Indigenous Theory in Approaching Māori Literature. ARIEL A Rev. Int. Engl. Lit. 2020, 51, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Data analysis and representation. In Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 2nd ed.; Creswell, J., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 179–212. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, R. Decolonizing both researcher and research and its effectiveness in Indigenous research. Res. Ethics 2017, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- At the Interface: Indigenous Health Practitioners and Evidence-Based Practice. Available online: https://www.nccih.ca/docs/context/RPT-At-the-Interface-Halseth-EN.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Gonzales, J.; Simard, E.; Baker-Demaray, T.; Iron Eyes, C. The Internalized Oppression of North America’s Indigenous Peoples. In Internalized Oppression: The Psychology of Marginalized Groups; David, E.J.R., Ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart, M.Y.H. The return to the sacred path: Healing the historical trauma and historical unresolved grief response among the Lakota. Smith Coll. Stud. Soc. Work 1998, 68, 3287–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, C.; Boel-Studt, S.; Renner, L.M.; Figley, C. The Historical Oppression Scale: Preliminary conceptualization and measurement of historical oppression among Indigenous peoples of the United States. J. Transcult. Psychiatry 2020, 57, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.; Tsourtos, G.; Lawn, S. The barriers and facilitators that indigenous health workers experience in their workplace and communities in providing self-management support: A multiple case study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGough, S. Experience of providing cultural safety in mental health to Aboriginal patients: A grounded theory study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 27, 2014–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks-Cleator, L.; Phillipps, B.; Giles, A. Culturally Safe Health Initiatives for Indigenous Peoples in Canada: A Scoping Review. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 50, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepler, E.; Martell, R.C. Indigenous model of care to health and social care workforce planning. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2018, 32, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavoie, J.G.; Dwyer, J. Implementing Indigenous community control in healthcare: Lessons from Canada. Aust. Health Rev. 2016, 40, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, J.M.; Lavoie, J.; O’Donnell, K.; Marlina, U.; Sullivan, P. Contracting for Indigenous Health Care: Towards Mutual Accountability. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2011, 70, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, B. Towards the achievement of IND-equity—A Culturally Relevant Health Equity Model By/For Indigenous Populations. Can. J. Crit. Nurs. Discourse 2020, 2, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights-Based Approach. Available online: https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/priorities-priorites/human_rights-droits_personne.aspx?lang=eng (accessed on 28 August 2021).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Smye, V.; Hill, B.; Antone, J.; MacDougall, A. Exploration of Existing Integrated Mental Health and Addictions Care Services for Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115946

Wu J, Smye V, Hill B, Antone J, MacDougall A. Exploration of Existing Integrated Mental Health and Addictions Care Services for Indigenous Peoples in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115946

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jasmine, Victoria Smye, Bill Hill, Joseph Antone, and Arlene MacDougall. 2023. "Exploration of Existing Integrated Mental Health and Addictions Care Services for Indigenous Peoples in Canada" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115946

APA StyleWu, J., Smye, V., Hill, B., Antone, J., & MacDougall, A. (2023). Exploration of Existing Integrated Mental Health and Addictions Care Services for Indigenous Peoples in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5946. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115946