The Professional Identity of Social Workers in Mental Health Services: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stage One: Identifying the Research Question

- Provide an overview of current understandings and perspectives of social workers in mental health settings on their professional role and identity;

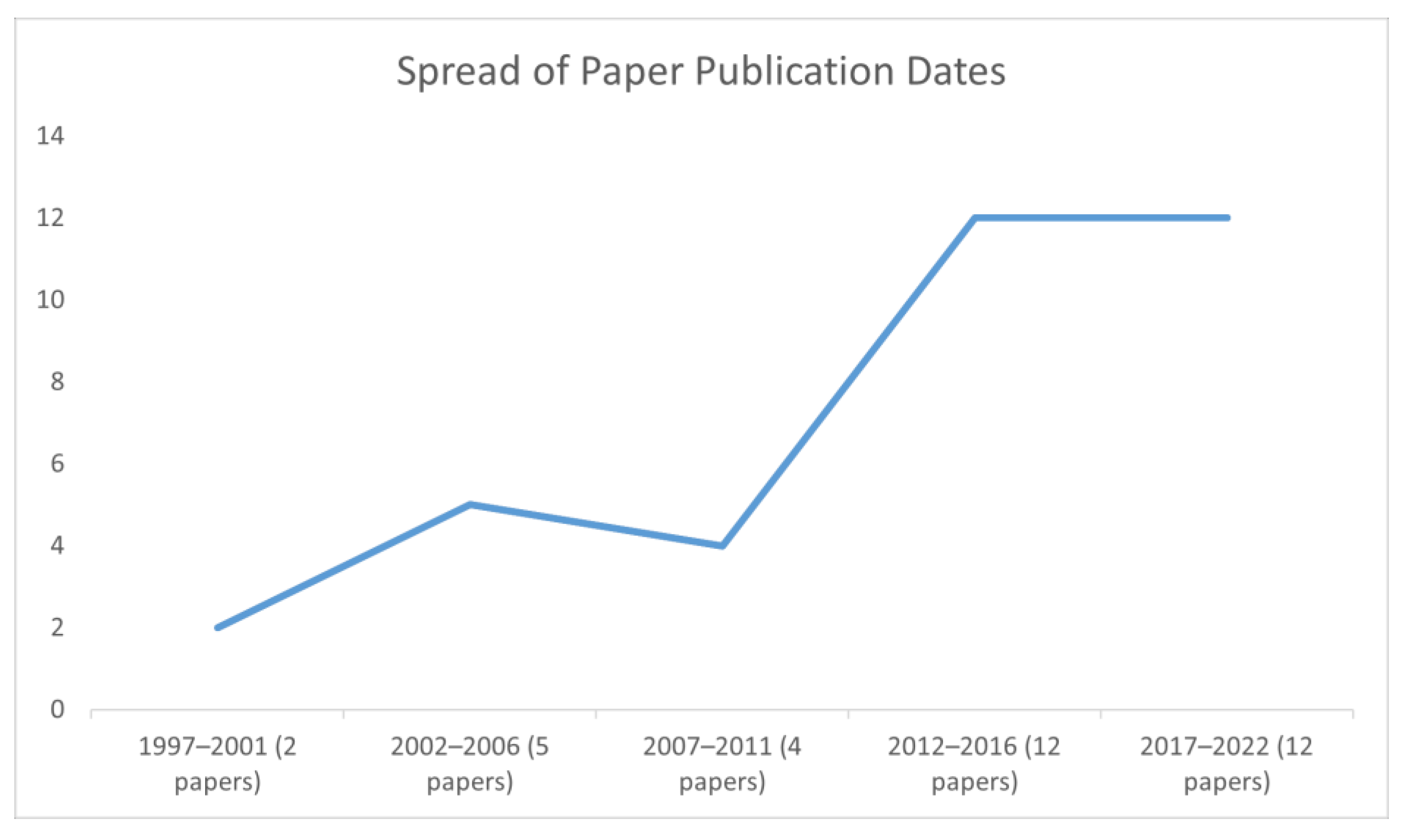

- Identify research trends within the existing literature and research;

- Identify gaps in extant research;

- Make recommendations for future research.

2.2. Stage Two: Identifying Relevant Studies

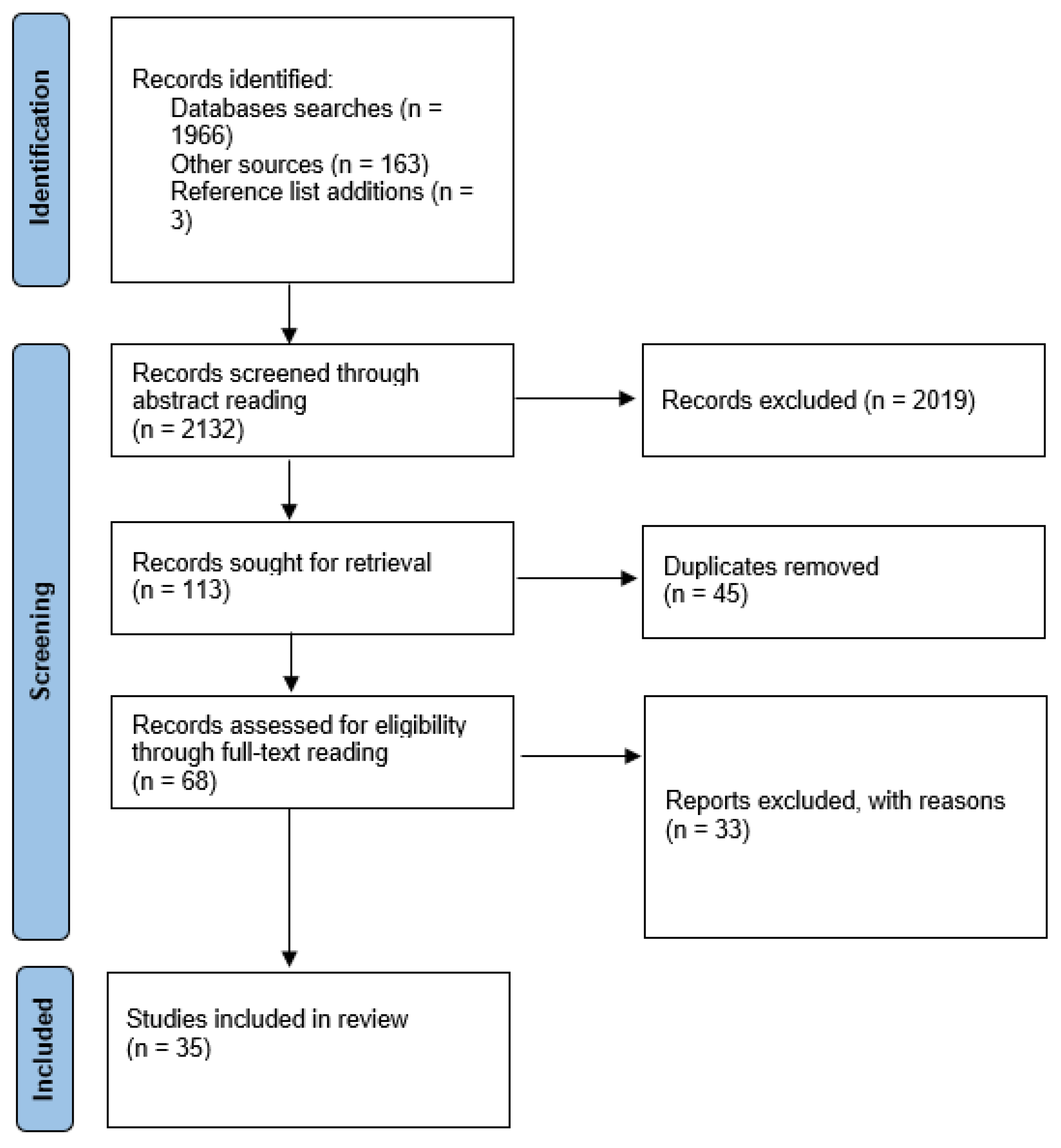

2.3. Stage Three: Study Selection

2.4. Stage Four: Charting the Data

2.5. Stage Five: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

3. Results

3.1. Distinctive Contributions

3.1.1. Social Approaches and Values

3.1.2. Legal Roles

3.2. Organizational Negotiations

3.2.1. Organizational Demands

3.2.2. Interprofessional Dynamics

3.2.3. Bridging

3.3. Professional Negotiations

3.3.1. Supervision and Reflection

3.3.2. Professional Flexibility

4. Discussion

4.1. Distinctive Contributions

4.1.1. Social Approaches and Values

4.1.2. Law

4.2. Organizational Negotiations

4.2.1. Evidence-Based Practice and Competing Professions

4.2.2. Co-Option and Erasure

‘the field of mental health continues to be over-medicalized and the reductionist biomedical model, with support from psychiatry and the pharmaceutical industry, dominates clinical practice, policy, research agendas, medical education and investment in mental health around the world’ [19] (pp. 5–6).

4.3. Professional Contributions

Bridging and Multiple Identities

4.4. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tew, J. Social Approaches to Mental Distress; Red Globe Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tew, J. A crisis of meaning: Can ‘schizophrenia’ survive in the 21st century? Med. Humanit. 2017, 43, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tew, J.; Ramon, S.; Slade, M.; Bird, V.; Melton, J.; Le Boutillier, C. Social Factors and Recovery from Mental Health Difficulties: A Review of the Evidence. Br. J. Soc. Work 2011, 42, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, R.; Kourgiantakis, T.; Fearing, G.; Robertson, T.; Brown, J.B. Social Work’s Scope of Practice in Primary Mental Health Care: A Scoping Review. Br. J. Soc. Work 2019, 49, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.L.; Harms, L.; Brophy, L. Factors Influencing Social Work Identity in Mental Health Placements. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 2198–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S. (Ed.) Professional Identity as a Matter of Concern. In Professional Identity and Social Work; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 226–239. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Executive. Changing Lives: Report of the 21st Century Social Work Review; Scottish Executive: Edinburgh, UK, 2006.

- Morriss, L. Being Seconded to a Mental Health Trust: The (In)Visibility of Mental Health Social Work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 1344–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røysum, A. ‘How’ we do social work, not ‘what’ we do. Nord. Soc. Work Res. 2017, 7, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, S.R.; Slotnick, H.B. Proto-Professionalism: How Professionalisation Occurs across the Continuum of Medical Education. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cribb, A.; Gewitz, S. Professionalism; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, J.; Richter, D. Contemporary Public Perceptions of Psychiatry: Some Problems for Mental Health Professions. Soc. Theory Health 2018, 16, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forenza, B.; Eckert, C. Social Worker Identity: A Profession in Context. Soc. Work 2017, 63, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywaters, P. Social Work and the Medical Profession: Arguments against Unconditional Collaboration. Br. J. Soc. Work 1986, 16, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, M.; Barry, J. New Public Management and the Professions in the UK: Reconfiguring Control? In Questioning the New Public Management; Dent, M., Chandler, J., Barry, J., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2004; pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, C. The ‘New Public Management’ in the 1980s: Variations on a Theme. Account. Organ. Soc. 1995, 20, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, E. Introduction: Taking Stock of Medical Dominance. Health Sociol. Rev. 2006, 15, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, N. Mental Health Social Work in Context; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health, Report No. A/HRC/35/21. 2017. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G17/076/04/PDF/G1707604.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- World Health Organization; Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Social Determinants of Mental Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidance on Community Mental Health Services: Promoting Person-Centred and Rights-Based Approaches. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025707 (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- International Federation of Social Workers: Global Definition of Social Work. Available online: https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/ (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- McCusker, P.; Jackson, J. Social Work and Mental Distress: Articulating the Connection. Br. J. Soc. Work 2015, 46, 1654–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, T.; Nett, J.; Bromfield, L.; Hietamäki, J.; Kindler, H.; Ponnert, L. Child protection in Europe: Development of an international cross-comparison model to inform national policies and practices. Br. J. Soc. Work 2015, 45, 1508–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, S.; Farioli, A.; Cooke, R.; Baldasseroni, A.; Ruotsalainen, J.; Placidi, D. Hidden Effectiveness? Results of Hand-Searching Italian Language Journals for Occupational Health Interventions. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Peacock, R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2005, 331, 1064–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badger, D.; Nursten, J.; Williams, P.; Woodward, M. Should All Literature Reviews be Systematic? Eval. Res. Educ. 2000, 14, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsea, T.C. Strategies to destigmatize mental illness in South Africa: Social work perspective. Soc. Work Health Care 2017, 56, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, E.N.; Petersen, A.; Kaae, A.M.; Petersen, H. Cross-sector problems of collaboration in psychiatry. Dan. Med. J. 2013, 60, A4707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, J.; Schneider, J.; Brandon, T.; Wooff, D. Working in Multidisciplinary Community Mental Health Teams: The Impact on Social Workers and Health Professionals of Integrated Mental Health Care. Br. J. Soc. Work 2003, 33, 1081–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, N.I.; Berenzon, S.; Galván, J. The role of social workers in mental health care: A study of primary care centers in Mexico. Qual. Soc. Work 2019, 18, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abendstern, M.; Tucker, S.; Wilberforce, M.; Jasper, R.; Brand, C.; Challis, D. Social Workers as Members of Community Mental Health Teams for Older People: What Is the Added Value? Br. J. Soc. Work 2016, 46, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merighi, J.R.; Ryan, M.; Renouf, N.; Healy, B. Reassessing a Theory of Professional Expertise: A Cross-National Investigation of Expert Mental Health Social Workers. Br. J. Soc. Work 2005, 35, 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.; Liyanage, L. The role of the mental health social worker: Political pawns in the reconfiguration of adult health and social care. Br. J. Soc. Work 2012, 42, 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K.S. Recovery Model of Mental Illness: A Complementary Approach to Psychiatric Care. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2015, 37, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krayer, A.; Robinson, C.A.; Poole, R. Exploration of joint working practices on anti-social behaviour between criminal justice, mental health and social care agencies: A qualitative study. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, e431–e441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.; Gabe, J. Risk and liminality in mental health social work. Health Risk Soc. 2004, 6, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leah, C. The Role of the Approved Mental Health Professional: A ‘Fool’s Errand’? Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 3802–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. Accredited Mental Health Social Work in Australia: A Reality Check. Aust. Soc. Work 2013, 66, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, D.; Kirwan, G. Exploring resilience and mental health in services users and practitioners in Ireland and Canada. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2018, 23, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, S. A Study Exploring How Social Work AMHPs Experience Assessment under Mental Health Law: Implications for Human Rights-Oriented Social Work Practice. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 1362–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, D.; Quinn, N. The context of risk management in mental health social work. Practice 2012, 24, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressington, D.T.; Wells, H.; Graham, M. A concept mapping exploration of social workers’ and mental health nurses’ understanding of the role of the Approved Mental Health Professional. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregor, C. Unconscious aspects of statutory mental health social work: Emotional labour and the approved mental health professional. J. Soc. Work Pract. 2010, 24, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morriss, L. AMHP Work: Dirty or Prestigious? Dirty Work Designations and the Approved Mental Health Professional. Br. J. Soc. Work 2016, 46, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, Y.; Johnson, S.; Morant, N.; Kuipers, E.; Szmukler, G.; Thornicroft, G.; Bebbington, P.; Prosser, D. Explanations for stress and satisfaction in mental health professionals: A qualitative study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1999, 34, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karban, K.; Sparkes, T.; Benson, S.; Kilyon, J.; Lawrence, J. Accounting for Social Perspectives: An Exploratory Study of Approved Mental Health Professional Practice. Br. J. Soc. Work 2021, 51, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.; Webber, M. ‘Maybe a Maverick, Maybe a Parent, but Definitely Not an Honorary Nurse’: Social Worker Perspectives on the Role and Nature of Social Work in Mental Health Care. Br. J. Soc. Work 2020, 51, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, K.; McCusker, P.; Davidson, G.; Vicary, S. An Exploratory Survey of Mental Health Social Work in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abendstern, M.; Hughes, J.; Wilberforce, M.; Davies, K.; Pitts, R.; Batool, S.; Robinson, C.; Challis, D. Perceptions of the social worker role in adult community mental health teams in England. Qual. Soc. Work 2021, 20, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.; Manthorpe, J.; Szymczynska, P.; Clewett, N.; Larsen, J.; Pinfold, V.; Tew, J. Implementing personalisation in integrated mental health teams in England. J. Interprofessional Care 2015, 29, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxley, P.; Evans, S.; Gately, C.; Webber, M.; Mears, A.; Pajak, S.; Kendall, T.; Medina, J.; Katona, C. Stress and Pressures in Mental Health Social Work: The Worker Speaks. Br. J. Soc. Work 2005, 35, 1063–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, P. Religion and spirituality as troublesome knowledge: The views and experiences of mental health social workers in Northern Ireland. Br. J. Soc. Work 2016, 46, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, E.; del Barrio, L.R. Recovery-Oriented Mental Health Practice: A Social Work Perspective. Br. J. Soc. Work 2015, 45, i27–i44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, K. Medicalization of Social Workers in Mental Health Services in Hong Kong. Br. J. Soc. Work 2004, 34, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerseth, R.; Dysvik, E. Health professionals’ experiences of person-centered collaboration in mental health care. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2008, 2, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaternik, I.; Grebenc, V. The role of social work in the field of mental health: Dual diagnoses as a challenge for social workers. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 2009, 12, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallonee, J.; Gergerich, E.; Gherardi, S.; Allbright, J. The impact of COVID-19 on social work mental health services in the United States: Lessons from the early days of a global pandemic. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2022, 20, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emprechtinger, J.; Voll, P. Inter-Professional Collaboration: Strengthening or Weakening Social Work Identity? In Professional Identity and Social Work; Webb, S., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Beddoe, L. A ‘Profession of Faith’ or a Profession: Social Work, Knowledge and Professional Capital. N. Z. Sociol. 2013, 28, 44–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, S. (Ed.) Matters of Professional Identity and Social Work. In Professional Identity and Social Work; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski, S. Social Work: The Rise and Fall of a Profession? 2nd ed.; Polity Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N. Obstacles and Dilemmas in the Delivery of Direct Payments to Service Users with Poor Mental Health. Practice 2008, 20, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, M. Perspectives on Professional Identity: The Changing World of the Social Worker. In Professional Identity and Social Work; Webb, S., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, M. ‘Have You Seen My Assessment Schedule?’ Proceduralisation, Constraint and Control in Social Work with Children and Families. In Questioning the New Public Management; Dent, M., Chandler, J., Barry, J., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2004; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Beddoe, L. Field, Capital and Professional Identity: Social Work in Health Care. In Professional Identity and Social Work; Webb, S., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, D. Medical dominance then and now: Critical reflections. Health Sociol. Rev. 2006, 15, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, S.; Kenny, A.; McKinstry, C. The meaning of recovery in a regional mental health service: An action research study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Amering, M.; Farkas, M.; Hamilton, B.; O’Hagan, M.; Panther, G.; Perkins, R.; Shepherd, G.; Tse, S.; Whitley, R. Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilberforce, M.; Tucker, S.; Abendstern, M.; Brand, C.; Giebel, C.; Challis, D. Membership and management: Structures of inter-professional working in community mental health teams for older people in England. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 1485–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.; Duggan, M.; Joseph, S. Relationship-based social work and its compatibility with the person-centred approach: Principled versus instrumental perspectives. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2013, 43, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Social Workers as Boundary Spanners: Reframing our Professional Identity for Interprofessional Practice. Soc. Work. Educ. 2013, 32, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, F. What is Professional Identity and How Do Social Workers Acquire It? In Professional Identity and Social Work; Webb, S., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Search Terms | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“social work*” AND “mental health*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“professional identit*” OR values OR duties OR duty OR roles OR role OR jobs OR job OR work OR requirements) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (experienc* OR view OR perspective* OR understanding OR perce*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (qualitative)) | 660 |

| Web of Science | (((TS = (“social work*” AND “mental health*”)) AND TS = (“professional identit*” OR values OR duties OR duty OR roles OR role OR jobs OR job OR work OR requirements)) AND TS = (experienc* OR view OR perspective* OR understanding OR perce*)) AND TS = (qualitative) | 796 |

| IBSS | noft(“social work*” AND “mental health*”) AND noft(“professional identit*” OR values OR duties OR duty OR roles OR role OR jobs OR job OR work OR requirements) AND noft(experienc* OR view OR perspective* OR understanding OR perce*) AND noft(qualitative) | 253 |

| APA PsychNet | Abstract: “social work*” AND “mental health*” AND Abstract: “professional identit*” OR values OR duties OR duty OR roles OR role OR jobs OR job OR work OR requirements AND Abstract: experienc* OR Abstract: view OR Abstract: perspective* OR Abstract: understanding OR Abstract: perce* AND Abstract: qualitative AND Peer-Reviewed Journals only | 144 |

| Social and Policy Practice | (social work* and mental health* and (professional identit* or values or duties or duty or roles or role or jobs or job or work or requirements) and (experienc* or view or perspective* or understanding or perce*) and qualitative).ab. | 87 |

| Jstor | (Title: “social work*” AND “mental health*”) AND (All fields: “professional identit*” OR values OR duties OR duty OR roles OR role OR jobs OR job OR work OR requirements) AND (All fields: experienc* OR view OR perspective* OR understanding OR perce*) AND (All fields: qualitative) | 26 |

| Journal Title | ||

| British Journal of Social Work | Title: social work* AND mental health* Abstract: professional identit* OR values OR duties OR duty OR roles OR role OR jobs OR job OR work OR requirements experienc* OR view OR perspective* OR understanding OR perce* qualitative | 85 |

| Journal of Social Work | (Title: social work* AND mental health*) AND (Abstract: professional identit* OR values OR duties OR duty OR roles OR role OR jobs OR job OR work OR requirements) AND (Abstract: experienc* OR view OR perspective* OR understanding OR perce*) AND (Abstract: qualitative) | 30 |

| Journal of Social Work Practice | [Publication Title: “social work*”] AND [Publication Title: “mental health*”] AND [[All: “professional identit*”] OR [All: values] OR [All: duties] OR [All: duty] OR [All: roles] OR [All: role] OR [All: jobs] OR [All: job] OR [All: work] OR [All: requirements]] AND [[All: experienc*] OR [All: view] OR [All: perspective*] OR [All: understanding] OR [All: perce*]] AND [All: qualitative] | 5 |

| Social Work in Mental Health | [Publication Title: “social work*”] AND [Publication Title: “mental health*”] AND [[All: “professional identit*”] OR [All: values] OR [All: duties] OR [All: duty] OR [All: roles] OR [All: role] OR [All: jobs] OR [All: job] OR [All: work] OR [All: requirements]] AND [[All: experienc*] OR [All: view] OR [All: perspective*] OR [All: understanding] OR [All: perce*]] AND [All: qualitative] | 23 |

| Australian Social Work Practice | [Publication Title: “social work*”] AND [Publication Title: “mental health*”] AND [[All: “professional identit*”] OR [All: values] OR [All: duties] OR [All: duty] OR [All: roles] OR [All: role] OR [All: jobs] OR [All: job] OR [All: work] OR [All: requirements]] AND [[All: experienc*] OR [All: view] OR [All: perspective*] OR [All: understanding] OR [All: perce*]] AND [All: qualitative] | 7 |

| European Journal of Social Work | [Publication Title: “social work*”] AND [Publication Title: “mental health*”] AND [[All: “professional identit*”] OR [All: values] OR [All: duties] OR [All: duty] OR [All: roles] OR [All: role] OR [All: jobs] OR [All: job] OR [All: work] OR [All: requirements]] AND [[All: experienc*] OR [All: view] OR [All: perspective*] OR [All: understanding] OR [All: perce*]] AND [All: qualitative] | 4 |

| Social Work | Journal: Social Work Title: social work* AND mental health* Abstract: professional identit* OR values OR duties OR duty OR roles OR role OR jobs OR job OR work OR requirements Abstract: experienc* OR view OR perspective* OR understanding OR perce* qualitative | 9 |

| ‘Snowball’ Sampling | 3 | |

| Total: 2132 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bark, H.; Dixon, J.; Laing, J. The Professional Identity of Social Workers in Mental Health Services: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115947

Bark H, Dixon J, Laing J. The Professional Identity of Social Workers in Mental Health Services: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(11):5947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115947

Chicago/Turabian StyleBark, Harry, Jeremy Dixon, and Judy Laing. 2023. "The Professional Identity of Social Workers in Mental Health Services: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 11: 5947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115947

APA StyleBark, H., Dixon, J., & Laing, J. (2023). The Professional Identity of Social Workers in Mental Health Services: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20115947