The Feasibility and Acceptability of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire in Danish Antenatal Care—A Qualitative Study of Midwives’ Implementation Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Antenatal Care in Denmark

1.2. The ACE Questionnaire in a Danish Antenatal Care Setting

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Recruitment of Study Participants

2.3. Ethical Considerations

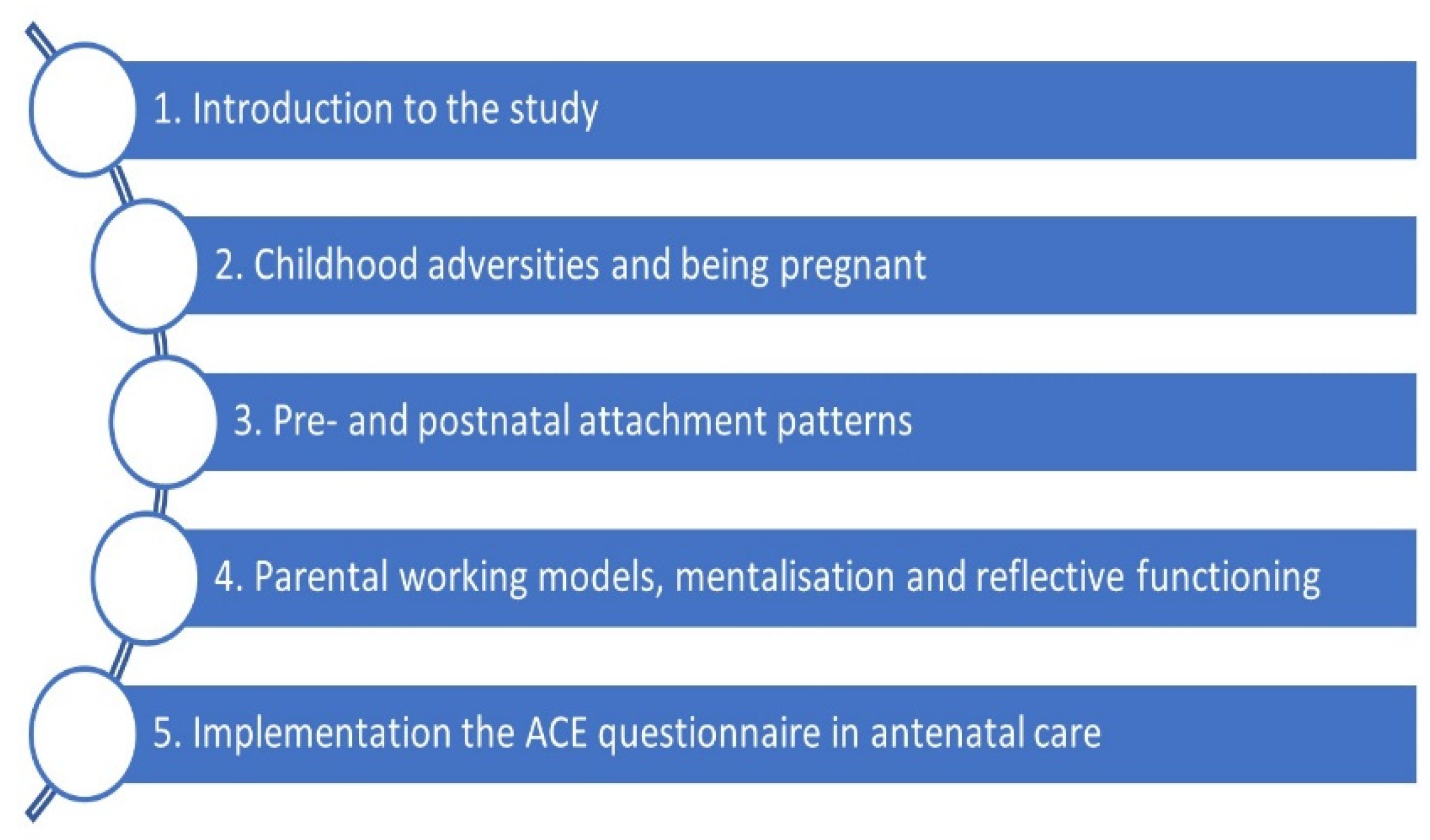

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Observations and Informal Conversations

2.4.2. Mini Group Interviews and Dialogue Meetings with Midwives

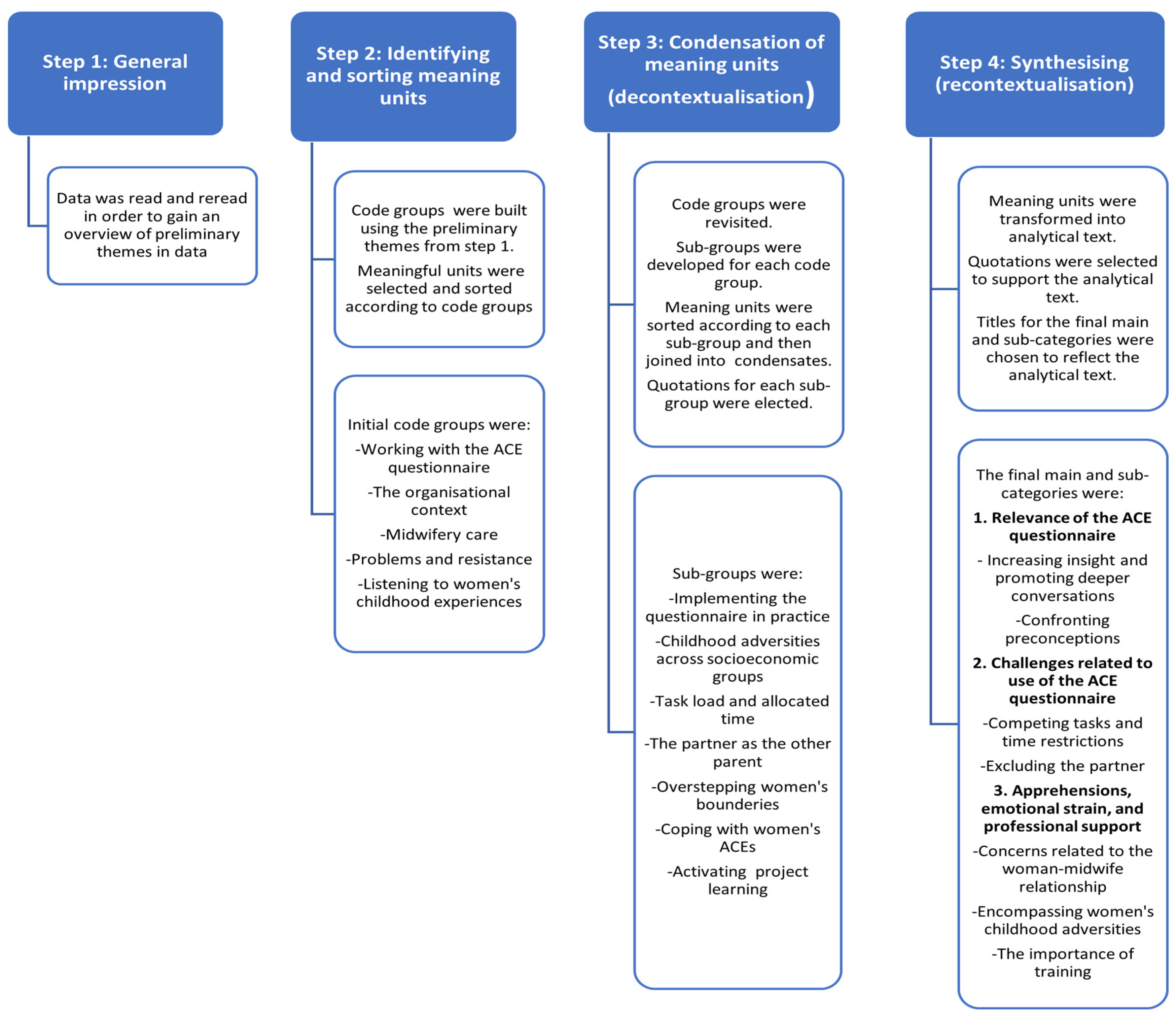

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Relevance of the ACE Questionnaire

3.1.1. Increasing Insight and Promoting Deeper Conversations

“…It is a really good tool…these women were not referred to extended antenatal care services…they wouldn’t have been caught otherwise. It (the questionnaire) has accentuated, why it makes sense to ask them…” (M3, DM3)

“I see women, who open up, because they sense, this (the midwifery visit) is a room, where there is space to talk about difficult things.” (O9)

“…I don’t think I have had anyone who has refused it (the ACE questionnaire) …my experience is that women generally are very open, and they are happy to tell me what concerns them…it’s a good idea to explain why we think this (the questionnaire) is important…I have had some conversations that I have never had before.” (M4, MG3)

“…She had been sexually abused during several years of her childhood. It was her third child, and it hadn’t been previously identified in antenatal care…it was difficult for her to be touched and examined…she felt that midwives had reacted negatively towards her...I referred her to a midwifery team specialising in antenatal care for vulnerable women…” (M1, MG4)

“I asked her…what thoughts she had regarding breastfeeding, and if there was anything, we (the maternity care providers) should be aware of with regards to her body when starting to breastfeed…it was important for her that nobody used the hands on approach…It’s written in her birth plan.” (M1, MG1)

“…She had been referred to antenatal care level 2. I think, it should have been antenatal care level 3. It (the visit) was somewhat difficult. There was a lot of mistrust towards the system. She had thoughts of the social authorities becoming involved, being reported, she felt unsafe, didn’t want to open that box.” (M1, DM4)

3.1.2. Confronting Preconceptions

“It was an apparently completely normal second pregnancy, there was absolutely nothing to put a finger on…I tell her that I will proceed to ask her the ten (ACE) questions, she is fine with that…she answers no to the first questions, and then we get to if she has ever been sexually abused as a child and she answers yes…a friend of the family had raped her.” (M3, MG3)

“……Are you bringing any psychological issues with you, have you been exposed to stress?…I could hear there was something buried here….When I introduced the ACE questionnaire, she scored positive. Then her story came, it was long…Her doctor hadn’t recorded it...these women pop up in midwifery care…you can’t see what baggage the women bring by looking at them.” (M2, MG1)

“…what becomes really clear, is that childhood trauma is seen in all societal levels. I saw a woman who is a doctor…there were several things she scored on even though she is a doctor…You don’t connect it to that kind of position, it (the ACE questionnaire) covers a wide range of people.” (M1, MG3)

“…I have had some women…they scored high on everything, very surprising, because it wasn’t those, I would normally be able to pick out.” (M3, MG1)

3.2. Challenges Related to the Use of the ACE Questionnaire

3.2.1. Competing Tasks and Time Restrictions

“I don’t find it difficult talking about it (the ACE questionnaire), but I am pushed on time. As a result, I am often late, and I use my lunchbreak on those women I didn’t get to.” (M2, DM 5)

“…I am nervous about opening the conversation about the ACE score because I don’t have the time.” (M2, DM6)

“…the time pressure. Some issues can be more important…a previous birth, pelvic pain, a scan result…I must prioritise…Even though I have prepared the ACE questionnaire…sometimes it has not been possible to use it.” (M2, MG4)

“…it can be a challenge, I am fairly new…if there is a lot the woman wants to talk about…we use all the time…it’s a shame when I get ten minutes extra to complete the (ACE) questionnaire.” (M4, MG1)

3.2.2. Excluding the Partner

“…It’s frustrating…we tell the women this is important and then we disregard the partner…it seems wrong.” (O2)

“…it’s a shame the initiative is primarily directed toward the woman, the partners childhood is just as important when becoming a family.” (O11)

“…The woman had scored six ACE points…the partner had said: my childhood was more violent, so it’s odd you don’t ask me.” (O10)

“The woman’s partner seemed uncomfortable when the woman had answered the ACE questions…He said: “I could say yes to eight of the questions. But there is no initiative for me.” (O12)

3.3. Apprehensions, Emotional Strain, and Professional Support

3.3.1. Concerns Related to the Woman–Midwife Relationship

“Maybe we will re-traumatise the women and what good is that when you can’t refer directly to a psychologist…” (M1, DM1)

“…some women, if you address what has been hard, abuse, violence and so forth…they may need ten therapy sessions before they can verbalise it…If we move too fast, they may shut down…we are not psychotherapists or psychologists, we need to be very aware of that…” (M5, MG1)

“…one of my concerns with the ACE questionnaire has been, what do we have to offer in cases where we think women’s problems are beyond our competencies…these women should be offered more help.” (M1, MG4)

“I prefer to establish a calm atmosphere before I move into their (the women’s) minds and private life.” (O6)

3.3.2. Encompassing Women’s Childhood Adversities

“I have to be all encompassing…but sometimes I feel a little like a garbage bin, which can contain everything, we (the midwives) are also human beings.” (M3, MG1)

“…It’s difficult questions you must ask. I can’t change what the women tell me they have experienced. But you need to be able to handle what they share…it’s not something we’ve learnt.” (M1, DM5)

3.3.3. The Importance of Support and Training

“…reading them (the ACE questions) out loud made me more certain that the women gave the right answers…but I also felt it (the interaction) became impersonal…it made it more detached.” (M4, MG3)

“…she (the teacher) said, they (the ACE questions) won’t make it worse for the women…Maybe they don’t see the connection…they may not think their childhood trauma can be of significance when they become a mother and that these issues may surface again…it (the ACE questionnaire) provided an opportunity to ask about the things we know are a little difficult to ask about.” (M2, MG3)

“There were many usable phrases…the fact that we had to practice conversation techniques on how to introduce the ACE questionnaire…I thought that was really good. I am sure I have many colleagues who are more lost regarding the aim of the initiative, those who didn’t participate (in the training course).” (M4, MG3)

“…I don’t get the same out of watching the online course. So I don’t really know how to approach it (the ACE questionnaire)…” (M2, DM3)

“I felt I was left on my own a lot…I found it hard to watch the online course. You can’t ask questions.” (M2, DM5)

“I noticed how different the midwives worked with the ACE questionnaire. It was useful to see, how some midwives were really good at integrating the ACE questionnaire in the conversations they were already having with the women.” (M1, MG3)

4. Discussion

Main Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bellis, M.A.; Hughes, K.; Ford, K.; Rodriguez, G.R.; Sethi, D.; Passmore, J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e517–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, R.; Kemp, A.; Thoburn, J.; Sidebotham, P.; Radford, L.; Glaser, D.; Macmillan, H.L. Recognising and responding to child maltreatment. Lancet 2009, 373, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Cheong, E.; Sinnott, C.; Dahly, D.; Kearney, P.M. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and later-life depression: Perceived social support as a potential protective factor. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmakis, K.A.; Chandler, G.E. Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2015, 27, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alhamzawi, A.O.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Butchart, A.; Felitti, V.J.; Brown, D.W. Building a Framework for Global Surveillance of the Public Health Implications of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, N.; Lemieux, R.; Garon-Bissonnette, J.; Muzik, M. Prenatal Attachment, Parental Confidence, and Mental Health in Expecting Parents: The Role of Childhood Trauma. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2020, 65, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudziak, J.J. ACEs and Pregnancy: Time to Support All Expectant Mothers. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20180023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rariden, C.; SmithBattle, L.; Yoo, J.H.; Cibulka, N.; Loman, D. Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences: Literature Review and Practice Implications. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.M. Integrative Review of Pregnancy Health Risks and Outcomes Associated With Adverse Childhood Experiences. JOGNN J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2018, 47, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young-Wolff, K.C.; Wei, J.; Varnado, N.; Rios, N.; Staunton, M.; Watson, C. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Pregnancy Intentions among Pregnant Women Seeking Prenatal Care. Women’s Health Issues 2021, 31, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young-Wolff, K.C.; Alabaster, A.; McCaw, B.; Stoller, N.; Watson, C.; Sterling, S.; Ridout, K.K.; Flanagan, T. Adverse childhood experiences and mental and behavioral health conditions during pregnancy: The role of resilience. J. Womens Health 2019, 28, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ångerud, K.; Annerbäck, E.M.; Tydén, T.; Boddeti, S.; Kristiansson, P. Adverse childhood experiences and depressive symptomatology among pregnant women. Acta Obs. Gynecol Scand 2018, 97, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N.; Zumwalt, K.; McDonald, S.; Tough, S.; Madigan, S. Perinatal depression: The role of maternal adverse childhood experiences and social support. J. Affect. Disord 2020, 263, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajid, A.; van Zanten, S.V.; Mughal, M.K.; Biringer, A.; Austin, M.-P.; Vermeyden, L.; Kingston, D. Adversity in childhood and depression in pregnancy. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2020, 23, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N.; Madigan, S.; Plamondon, A.; Hetherington, E.; McDonald, S.; Tough, S. Maternal adverse childhood experiences and antepartum risks: The moderating role of social support. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2018, 21, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, L.É.; Tarabulsy, G.M.; Pearson, J.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Gagné, L.M. Maternal history of childhood maltreatment and later parenting behavior: A meta-analysis. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, B.C.L.; Callinan, L.S.; Smith, M.V. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Their Relation to Parenting Stress and Parenting Practices. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullin, S.; Waldfogel, J.; Washbrook, E. Baby Bonds—Parenting, Attachment and a Secure Base for Children. 2014. Available online: https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/baby-bonds-final-1.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Hornor, G. Attachment Disorders. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2019, 33, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N.; Callaway, L.; Shen, S.; Biswas, T.; Scott, J.G.; Boyle, F.; Mamun, A. Screening for adverse childhood experiences in antenatal care settings: A scoping review. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 62, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, H.; Juhl, M.; Møller, B.K.; de Lichtenberg, V. Adult Daughters of Alcoholic Parents—A Qualitative Study of These Women’s Pregnancy Experiences and the Potential Implications for Antenatal Care Provision. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, J.; Rycroft-Malone, J.; Hawkes, C.; Noyes, J. Application of simplified Complexity Theory concepts for healthcare social systems to explain the implementation of evidence into practice. J. Adv. Nurs 2016, 72, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente. Finding Your ACE Score. 2006. Available online: https://www.ncjfcj.org/wp-content/uploads/2006/10/Finding-Your-Ace-Score.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Sundhedsstyrelsen. Anbefalinger for Svangreomsorgen. 2022. Available online: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2021/Anbefalinger-svangreomsorgen/Svangreomsorg-2022-ny.ashx (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Ministry of Health. LBK nr 210 af 27/01/2022. The National Health Act. 2022. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2022/210 (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Danske Regioner. Kortlægning af Svangreomsorgen- Et Overblik over Organisering, Aktivitet og Personaleressourcer i den Regionale Svangreomsorg. 2017. Available online: https://docplayer.dk/63819128-Kortlaegning-af-svangreomsorgen.html (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Felitti, M.D.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarse, E.M.; Neff, M.R.; Yoder, R.; Hulvershorn, L.; Chambers, J.E.; Chambers, R.A. The adverse childhood experiences questionnaire: Two decades of research on childhood trauma as a primary cause of adult mental illness, addiction, and medical diseases. Cogent Med. 2019, 6, 1581447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organization. Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ). 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/adverse-childhood-experiences-international-questionnaire-(ace-iq) (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System ACE Data. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/ace-brfss.html (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Flanagan, T.; Alabaster, A.; McCaw, B.; Stoller, N.; Watson, C.; Young-Wolff, K.C. Feasibility and Acceptability of Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in Prenatal Care. J. Womens Health 2018, 27, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.; Royse, C.; Terkawi, A. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2017, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banville, D.; Desrosiers, P.; Genet-Volet, Y. Translating Questionnaires and Inventories Using a Cross-Cultural Translation Technique. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2000, 19, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organization. Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences to Improve Public Health: Expert Consultation, 4–5 May 2009 Meeting Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organization. WHODAS 2.0 Translation Package (Version 1.0). Translation and Linguistic Evaluation Protocol and Supporting Material. 2023. Available online: https://terrance.who.int/mediacentre/data/WHODAS/Guidelines/WHODAS%202.0%20Translation%20guidelines.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Eldridge, S.M.; Lancaster, G.A.; Campbell, M.J.; Thabane, L.; Hopewell, S.; Coleman, C.L.; Bond, C.M. Defining Feasibility and Pilot Studies in Preparation for Randomised Controlled Trials: Development of a Conceptual Framework. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathain, A.; Hoddinott, P.; Lewin, S.; Thomas, K.J.; Young, B.; Adamson, J.; Jansen, Y.J.; Mills, N.; Moore, G.; Donovan, J.L. Maximising the impact of qualitative research in feasibility studies for randomised controlled trials: Guidance for researchers. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2015, 1, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv. Res. 1999, 34, 1189–1208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Indenrigs og Sundhedsministeriet. VEJ nr 11052 af 02/07/1999. Vejledning om Indførelse af Nye Behandlinger i Sundhedsvæsenet. 1999. Available online: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/retsinfo/1999/11052 (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Datatilsynet. Særligt om Sundhedsområdet. 2023. Available online: https://www.datatilsynet.dk/hvad-siger-reglerne/vejledning/forskning-og-statistik/saerligt-om-sundhedsomraadet (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- National Committee on Health Research Ethics. What to Notify. Available online: https://nationaltcenterforetik.dk/ansoegerguide/overblik/hvad-skal-jeg-anmelde (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Gold, R.L. Roles in sociological field observations. Soc. Forces 1958, 36, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, S.; Krogstrup, H.K. Deltagende Observation; Hans Reitzels Forlag: København, Danmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.B.S. Interview: Det Kvalitative Forskningsinterview Som Håndværk; Hans Reitzels Forlag: København, Danmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Thoreood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 1–342. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. Kvalitative Forskningsmetoder for Medisin og Helsefag: En Innføring; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle, K.B.M.A. Asking about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in Health Visiting-Findings from a Pilot Study. 2019. Available online: https://phw.nhs.wales/services-and-teams/policy-and-international-health-who-collaborating-centre-on-investment-for-health-well-being/publications-and-resources-bucket/asking-about-adverse-childhood-experiences-aces-in-health-visiting-findings-fro/ (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Gillespie, R.J.; Folger, A.T. Feasibility of Assessing Parental ACEs in Pediatric Primary Care: Implications for Practice-Based Implementation. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2017, 10, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsicek, S.M.; Morrison, J.M.; Manikonda, N.; O’Halleran, M.; Spoehr-Labutta, Z.; Brinn, M. Implementing Standardized Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in a Pediatric Resident Continuity Clinic. Pediatr Qual. Saf. 2019, 4, e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek Sindberg, N.; Høeg, M.L. Sindberg, Kommende fædre oplever ekskludering: Mænd, der bliver fædre i dagens Danmark, ønsker at være involverede i deres børns liv, helt fra graviditeten. Men i kontakten med sundhedsvæsenet oplever de sig ekskluderede. Tidsskr. Jordemødre 2018, 9, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, H.; Stenback, P.; Halldén, B.M.; Svalenius, E.C.; Persson, E.K. Nordic fathers’ willingness to participate during pregnancy. J. Reprod. Infant. Psychol. 2017, 35, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machtinger, E.L.; Cuca, Y.P.; Khanna, N.; Rose, C.D.; Kimberg, L.S. From Treatment to Healing: The Promise of Trauma-Informed Primary Care. Women’s Health Issues 2015, 25, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, A. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Trauma-Informed Care. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2021, 35, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, M.S.; McLachlan, H.L.; Willis, K.F.; Forster, D.A. Comparing satisfaction and burnout between caseload and standard care midwives: Findings from two cross-sectional surveys conducted in Victoria, Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, I.; Juul, S.; Foureur, M.; Sørensen, E.E.; Nøhr, E.A. Is caseload midwifery a healthy work-form? A survey of burnout among midwives in Denmark. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2017, 11, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildingsson, I.; Westlund, K.; Wiklund, I. Burnout in Swedish midwives. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2013, 4, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortimore, V.; Richardson, M.; Unwin, S. Identifying adverse childhood experiences in maternity services. Br. J. Midwifery 2021, 29, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R.; Rodriguez, C.; Araujo, J.; Shaqlaih, A.; Moss, G. Constructivism—Constructivist learning theory. In The Handbook of Educational Theories; Irby, B.J., Brown, G., Lara-Alecio, R., Jackson, S., Eds.; IAP Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandall, J.; Soltani, H.; Gates, S.; Shennan, A.; Devane, D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 4, CD004667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnsen, H.; Lichtenberg, V.d.; Rydahl, E.; Karentius, S.M.; Dueholm, S.C.H.; Friis-Alstrup, M.; Backhausen, M.G.; Røhder, K.; Schiøtz, M.L.; Broberg, L.; et al. The Feasibility and Acceptability of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire in Danish Antenatal Care—A Qualitative Study of Midwives’ Implementation Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105897

Johnsen H, Lichtenberg Vd, Rydahl E, Karentius SM, Dueholm SCH, Friis-Alstrup M, Backhausen MG, Røhder K, Schiøtz ML, Broberg L, et al. The Feasibility and Acceptability of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire in Danish Antenatal Care—A Qualitative Study of Midwives’ Implementation Experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(10):5897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105897

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnsen, Helle, Vibeke de Lichtenberg, Eva Rydahl, Sara Mbaye Karentius, Signe Camilla Hjuler Dueholm, Majbritt Friis-Alstrup, Mette Grønbæk Backhausen, Katrine Røhder, Michaela Louise Schiøtz, Lotte Broberg, and et al. 2023. "The Feasibility and Acceptability of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire in Danish Antenatal Care—A Qualitative Study of Midwives’ Implementation Experiences" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 10: 5897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105897

APA StyleJohnsen, H., Lichtenberg, V. d., Rydahl, E., Karentius, S. M., Dueholm, S. C. H., Friis-Alstrup, M., Backhausen, M. G., Røhder, K., Schiøtz, M. L., Broberg, L., & Juhl, M. (2023). The Feasibility and Acceptability of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire in Danish Antenatal Care—A Qualitative Study of Midwives’ Implementation Experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105897