Clinicians’ and Users’ Views and Experiences of a Tele-Mental Health Service Implemented Alongside the Public Mental Health System during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

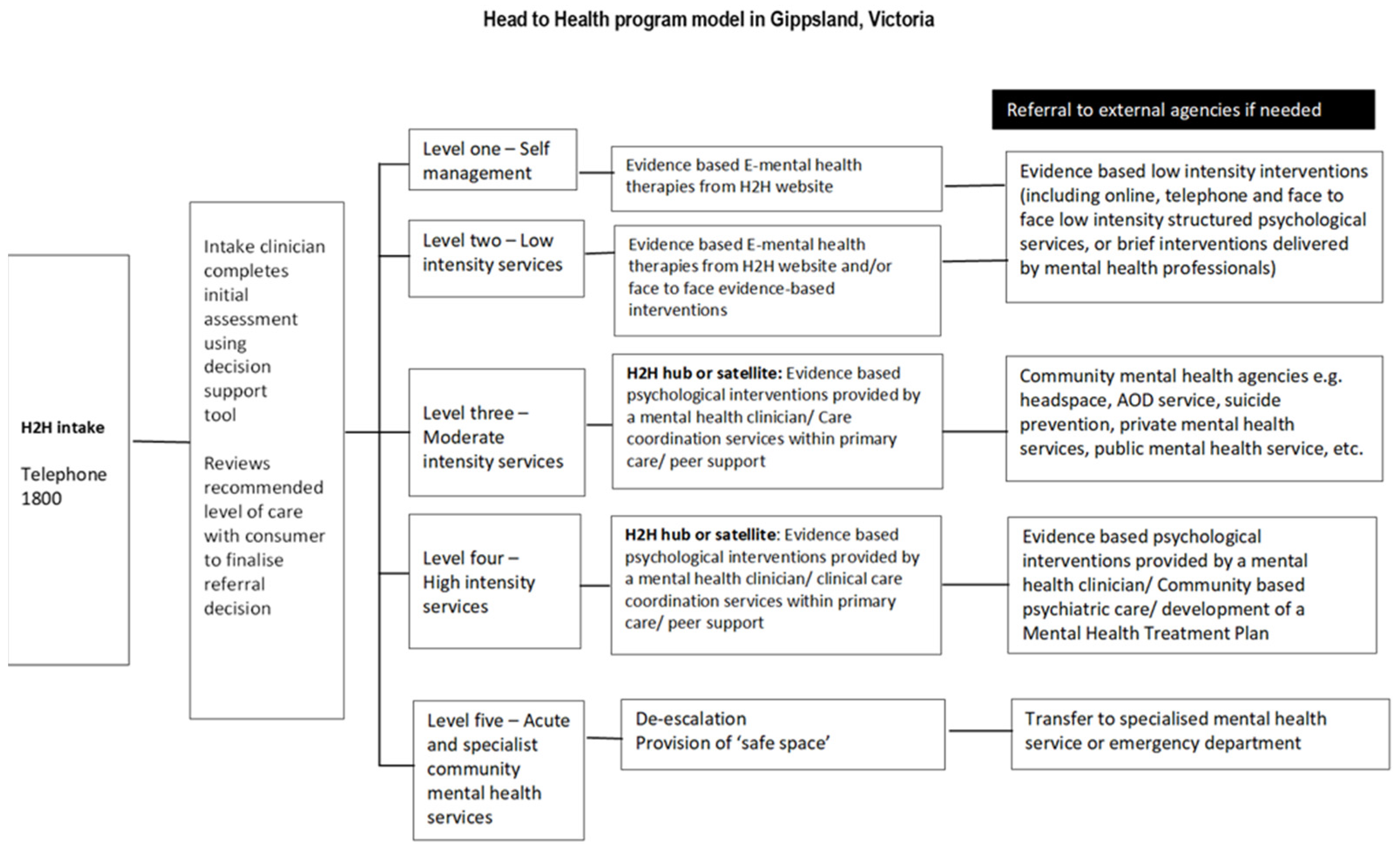

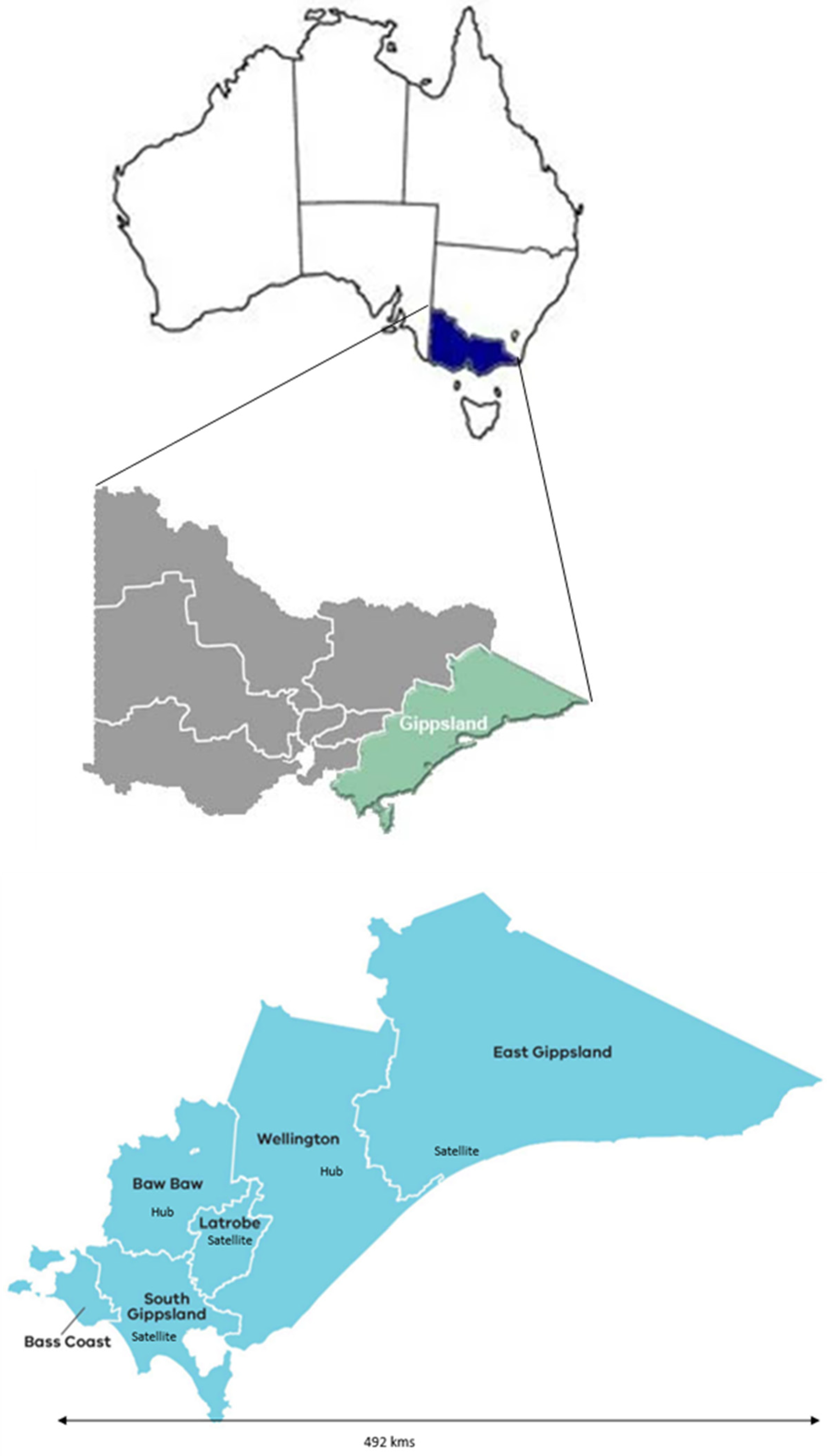

2.1. Setting

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participant Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Conditions Where Use of TMH Is Appropriate

3.2. Conditions Where TMH May Not Be Useful

3.3. Advantages of TMH

3.4. Challenges of Using TMH

3.5. Client Outcomes with TMH

3.6. Recommendations for Future Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Government Department of Health. Telehealth. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/e-health-telehealth (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Waugh, M.; Voyles, D.; Thomas, M.R. Telepsychiatry: Benefits and costs in a changing health-care environment. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whaibeh, E.; Mahmoud, H.; Naal, H. Telemental Health in the Context of a Pandemic: The COVID-19 Experience. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2020, 7, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, P.; Goulding, L.; Casetta, C.; Jordan, H.; Sheridan-Rains, L.; Steare, T.; Williams, J.; Wood, L.; Gaughran, F.; Johnson, S. Implementation of Telemental Health Services Before COVID-19: Rapid Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlbring, P.; Andersson, G. Internet and psychological treatment. How well can they be combined? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2006, 22, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uscher-Pines, L.; Sousa, J.; Raja, P.; Mehrotra, A.; Barnett, M.L.; Huskamp, H.A. Suddenly Becoming a “Virtual Doctor”: Experiences of Psychiatrists Transitioning to Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grist, R.; Porter, J.; Stallard, P. Mental Health Mobile Apps for Preadolescents and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, C.; Falconer, C.J.; Martin, J.L.; Whittington, C.; Stockton, S.; Glazebrook, C.; Davies, E.B. Annual Research Review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems—A systematic and meta-review. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2017, 58, 474–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harerimana, B.; Forchuk, C.; O’Regan, T. The use of technology for mental healthcare delivery among older adults with depressive symptoms: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flumignan, C.D.Q.; Rocha, A.P.D.; Pinto, A.; Milby, K.M.M.; Batista, M.R.; Atallah, Á.N.; Saconato, H. What do Cochrane systematic reviews say about telemedicine for healthcare? Sao Paulo Med. J. 2019, 137, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System. Final Report, Summary and Recommendations; Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System: Melbourne, Australia, 2021.

- ORYGEN. Defining the Missing Middle. Available online: https://www.orygen.org.au/Policy/Policy-Areas/Government-policy-service-delivery-and-workforce/Service-delivery/Defining-the-missing-middle/orygen-defining-the-missing-middle-pdf.aspx?ext=.#:~:text=The%20'missing%20middle'%20is%20a,enough%20for%20state%2Dbased%20services (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System. Final Report Volume 5: Transforming the System-Innovation and Implementation; Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://finalreport.rcvmhs.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/RCVMHS_FinalReport_Vol5_Accessible.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Ellis, L.A.; Meulenbroeks, I.; Churruca, K.; Pomare, C.; Hatem, S.; Harrison, R.; Zurynski, Y.; Braithwaite, J. The Application of e-Mental Health in Response to COVID-19: Scoping Review and Bibliometric Analysis. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e32948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National PHN Guidance. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/09/primary-health-networks-phn-mental-health-care-guidance-initial-assessment-and-referral-for-mental-health-care-national-phn-guidance-initial-assessment-and-referral-for-mental-health-care.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Australian Government Department of Health. Primary Health Networks. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/phn (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Australian Government. National PHN Guidance: Initial Assessment and Referral for Mental Healthcare. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/2126B045A8DA90FDCA257F6500018260/$File/National%20MH-IAR%20Guidance-%2030Aug2019_V1.02%20Accessible.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004, 82, 581–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bee, P.; Lovell, K.; Airnes, Z.; Pruszynska, A. Embedding telephone therapy in statutory mental health services: A qualitative, theory-driven analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, A.N.; Sutton, K.; Dalziel, K.; Maybery, D. Outcomes of a care coordinated service model for persons with severe and persistent mental illness: A qualitative study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, C.; Holloway, K.; Riley, G.; Auret, K. Online Mental Health Resources in Rural Australia: Clinician Perceptions of Acceptability. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, L.; Bidargaddi, N.; Schrader, G. Service providers’ experiences of using a telehealth network 12 months after digitisation of a large Australian rural mental health service. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 94, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Service User Experience in Adult Mental Health: Improving the Experience of Care for People Using Adult NHS Mental Health Services; British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 2011.

- Farrelly, S.; Brown, G.; Rose, D.; Doherty, E.; Henderson, R.C.; Birchwood, M.; Marshall, M.; Waheed, W.; Szmukler, G.; Thornicroft, G. What service users with psychotic disorders want in a mental health crisis or relapse: Thematic analysis of joint crisis plans. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1609–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, S.L.A.; Tchernegovski, P.; Maybery, D. Mental health service users’ experiences and perspectives of family involvement in their care: A systematic literature review. J. Ment. Health 2022, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Government of Victoria. Gippsland Regional Growth Plan. Available online: http://www.dtpli.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/229310/Gippsland-Regional-Growth-Plan-May-2014.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Nous Group. Nous Group. Independent Evaluation of HeadtoHelp and AMHCs: Final Evaluation Report. 2022; Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard, M.A.; Olesen, F.; Andersen, R.S.; Sondergaard, J. Qualitative description—The poor cousin of health research? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan-Bolyai, S.; Bova, C.; Harper, D. Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: The use of Qualitative Description. Nurs. Outlook 2005, 53, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics for Australia. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/au/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Otter.ai. Automated Transcription Made Easy. Available online: https://otter.ai/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Confusing Categories and Themes. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.E.; McKean, A.J.; Gentry, M.T.; Hilty, D.M. Barriers to Use of Telepsychiatry: Clinicians as Gatekeepers. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 2510–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughtrey, A.E.; Pistrang, N. The effectiveness of telephone-delivered psychological therapies for depression and anxiety: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, M.; Yellowlees, P.; Dixon, R.; Shore, J.H. Telepsychiatry. In Understanding Telehealth; Rheuban, K.S., Krupinski, E.A., Eds.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, D.; Gale, J.; Hartley, D.; Croll, Z.; Hansen, A. Understanding the Business Case for Telemental Health in Rural Communities. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2016, 43, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, E.K.; Goetter, E.M.; Herbert, J.D.; Forman, E.M. Challenges and opportunities in internet-mediated telemental health. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2012, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmann, E.; Köhnen, M.; Härter, M.; Liebherz, S. Therapeutic Alliance in Technology-Based Interventions for the Treatment of Depression: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, V.Q.; Bickler, A. Cultivating the Therapeutic Alliance in a Telemental Health Setting. Contemp. Fam. 2021, 43, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremain, H.; McEnery, C.; Fletcher, K.; Murray, G. The Therapeutic Alliance in Digital Mental Health Interventions for Serious Mental Illnesses: Narrative Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e17204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, H. Therapeutic Alliance in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy in Child and Adolescent Mental Health-Current Trends and Future Challenges. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 610874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Edirippulige, S.; Bai, X.; Bambling, M. Are online mental health interventions for youth effective? A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021, 27, 638–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uscher-Pines, L.; Raja, P.; Qureshi, N.; Huskamp, H.A.; Busch, A.B.; Mehrotra, A. Use of Tele-Mental Health in Conjunction With In-Person Care: A Qualitative Exploration of Implementation Models. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelber, H. The experience in Victoria with telepsychiatry for the child and adolescent mental health service. J. Telemed. Telecare 2001, 7, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feijt, M.; de Kort, Y.; Westerink, J.; Bierbooms, J.; Bongers, I.; IJsselsteijn, W. Integrating technology in mental healthcare practice: A repeated cross-sectional survey study on professionals’ adoption of Digital Mental Health before and during COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1040023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strand, M.; Gammon, D.; Ruland, C.M. Transitions from biomedical to recovery-oriented practices in mental health: A scoping review to explore the role of Internet-based interventions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disney, L.; Mowbray, O.; Evans, D. Telemental Health Use and Refugee Mental Health Providers Following COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2021, 49, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.; Taylor, K.; Mohebati, L.M.; Sundin, J.; Cooper, M.; Scanlon, T.; de Visser, R. Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: A qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Vaello, S.; Strode, A.; Sheeran, B.C. Using technology in the delivery of mental health and substance abuse treatment in rural communities: A review. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 40, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajgopal, A.; Li, C.R.; Shah, S.; Sundar Budhathoki, S. The use of telehealth to overcome barriers to mental health services faced by young people from Afro-Caribbean backgrounds in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 03040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Usher, K.; Jackson, D.; Reid, C.; Hopkins, K.; Shepherd, C.; Smallwood, R.; Marriott, R. Connection to Addressing Digital Inequities in Supporting the Well-Being of Young Indigenous Australians in the Wake of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Number (%) | Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age groups (years) | ||

| Women | 35 (74.5) | 20–29 | 8 (17.0) |

| Men | 12 (25.5) | 30–39 | 9 (19.1) |

| Primary professional roles (health professional) | 40–49 | 11 (23.4) | |

| General practitioner | 7 (14.9) | 50–59 | 9 (19.1) |

| Other medical | 1 (2.1) | 60 and older | 10 (21.3) |

| Mental health nurse | 3 (6.4) | ||

| Occupational therapist | 1 (2.1) | Mental health service experience in Gippsland | |

| Psychologist | 2 (4.3) | <1 year | 3 (6.4) |

| Social worker | 4 (8.5) | 1–5 years | 14 (29.8) |

| Mental health support worker | 7 (14.9) | 5–10 years | 4 (8.5) |

| Psychosocial support worker | 1 (2.1) | >10 years | 26 (55.3) |

| Alcohol and other drugs service worker | 1 (2.1) | Local government area | |

| Emergency department worker | 1 (2.1) | Baw Baw Shire | 9 (19.1) |

| East Gippsland Shire | 5 (10.6) | ||

| Primary professional roles (non-health practitioner) | Latrobe City | 17 (36.2) | |

| Department of Families, Fairness and Housing worker | 2 (4.2) | South Gippsland Shire | 4 (8.5) |

| Family violence service worker | 2 (4.3) | Wellington Shire | 11 (23.4) |

| Manager/administrator | 7 (14.9) | Non-Gippsland LGA | 1 (2.1) |

| Researcher/educator | 5 (10.6) | Location of practice in LGA * within Hub | |

| Volunteer | 1 (2.1) | Yes | 20 (42.6) |

| Other (not specified) | 2 (4.2) | No | 27 (57.4) |

| Identify as working in the mental health sector | |||

| Yes | 34 (72.3) | ||

| No | 13 (27.7) |

| Service User Characteristics | N (%) | Service User Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Housing | ||

| Woman | 14 (73.7) | Own home | 14 (73.7) |

| Man | 5 (26.3%) | Public rental | 3 (15.8) |

| Age (years) | Private rental | 1 (5.3) | |

| Mean | 47 years | Emergency housing | 1 (5.3) |

| Range | 22–77 years | Living arrangement | |

| Cultural background | Alone | 5 (26.3) | |

| Aboriginal | 2 (10.5) | With partner only | 6 (31.6) |

| Australian | 16 (84.2) | With partner and children | 3 (15.8) |

| Spanish | 1 (5.3) | With children only | 4 (21.1) |

| Sexuality | Did not disclose | 1 (5.3) | |

| Heterosexual | 17 (89.5) | Carer status | |

| LGBTQIA+ | 1 (5.3) | Has a carer | 1 (5.3) |

| Did not disclose | 1 (5.3) | Has no carer | 18 (94.7) |

| Employment status | Care for another person | 6 (31.6) | |

| Self-employed | 2 (10.5) | Past mental health problems | |

| Unemployed | 3 (15.8) | Stress | 2 (10.5) |

| Retired | 3 (15.8) | Anxiety | 6 (31.6) |

| Employed full-time | 6 (31.6) | Depression | 11 (57.9) |

| Full-time carer | 1 (5.3) | Borderline personality disorder | 4 (21.1) |

| Studying and working | 1 (5.3) | Grief | 1 (5.3) |

| Disability pension | 3 (15.8) | Post-traumatic stress disorder | 5 (26.3) |

| Highest educational attainment | Trauma | 3 (15.8) | |

| Year 8 | 2 (10.5) | Social phobia | 1 (5.3) |

| Year 11 | 2 (10.5) | Bipolar | 2 (10.5) |

| Year 12 | 2 (10.5) | Psychosis | 1 (5.3) |

| Certificate IV | 1 (5.3) | Dissociative identity disorder | 1 (5.3) |

| Diploma | 7 (36.8) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 3 (15.8) | ||

| Graduate diploma | 1 (5.3) | ||

| Master’s degree | 1 (5.3) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isaacs, A.; Mitchell, E.K.L.; Sutton, K.; Naughton, M.; Hine, R.; Bullock, S.; Azar, D.; Maybery, D. Clinicians’ and Users’ Views and Experiences of a Tele-Mental Health Service Implemented Alongside the Public Mental Health System during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105870

Isaacs A, Mitchell EKL, Sutton K, Naughton M, Hine R, Bullock S, Azar D, Maybery D. Clinicians’ and Users’ Views and Experiences of a Tele-Mental Health Service Implemented Alongside the Public Mental Health System during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(10):5870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105870

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsaacs, Anton, Eleanor K. L. Mitchell, Keith Sutton, Michael Naughton, Rochelle Hine, Shane Bullock, Denise Azar, and Darryl Maybery. 2023. "Clinicians’ and Users’ Views and Experiences of a Tele-Mental Health Service Implemented Alongside the Public Mental Health System during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 10: 5870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105870

APA StyleIsaacs, A., Mitchell, E. K. L., Sutton, K., Naughton, M., Hine, R., Bullock, S., Azar, D., & Maybery, D. (2023). Clinicians’ and Users’ Views and Experiences of a Tele-Mental Health Service Implemented Alongside the Public Mental Health System during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105870