Poverty-Aware Programs in Social Service Departments in Israel: A Rapid Evidence Review of Outcomes for Service Users and Social Work Practice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Poverty-Aware Social Work

1.2. The Implementation of the PAP

2. Methodology

2.1. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

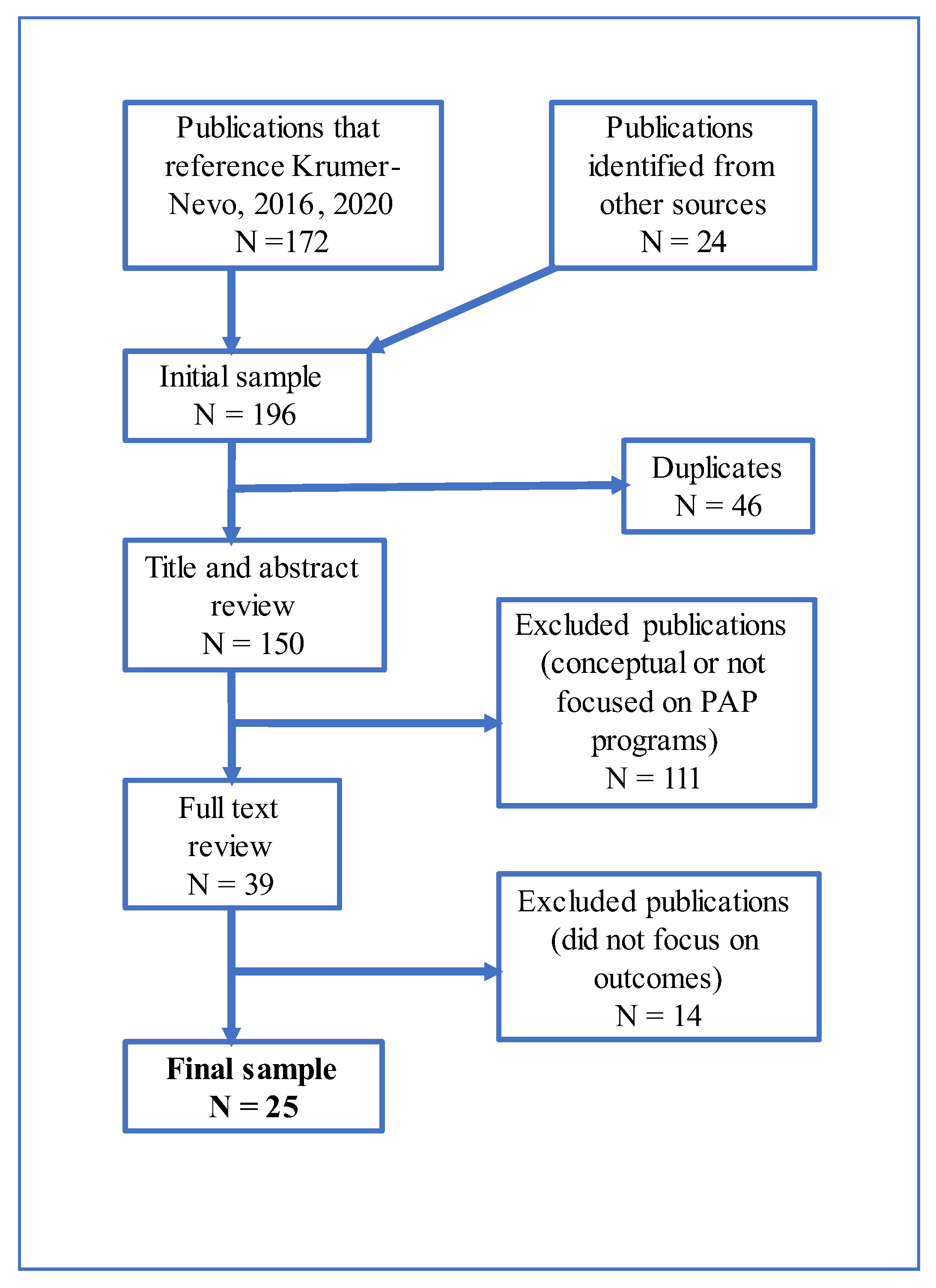

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Screening, Study Selection, and Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

2.5. Overview of the Sample

3. Findings

3.1. Evaluation of Outcomes for Service Users

3.1.1. Service Users’ Relationship with Social Workers and Their Willingness to Receive Professional Assistance

3.1.2. Service Users’ Financial Circumstances

3.1.3. Family Relationships

3.1.4. Children’s Safety and Well-Being

3.2. Evaluation of the PAP’s Impact on Social Workers’ Attitudes and Practices

3.2.1. Social Workers’ Attitudes toward Poverty and People in Poverty

3.2.2. Social Workers’ Implementation of PAP Practice

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Timor-Shlevin, S.; Roose, R.; Hermans, K. In search of social justice informed services: A research agenda for the study of resistance to neo-managerialism. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2022. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S. Introduction: Critical social work and the politics of transformation. In The Routledge Handbook of Critical Social Work; Webb, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Krumer-Nevo, M. Poverty-aware social work: A paradigm for social work practice with people in poverty. Br. J. Soc. Work 2016, 46, 1793–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Shlevin, S. Between conservatism, managerialism and criticism: A struggle over professionalization in Israeli social work. Soc. Secur. 2019, 106, 189–218. [Google Scholar]

- Saar-Heiman, Y.; Krumer-Nevo, M.; Lavie-Ajayi, M. Intervention in a real-life context: Therapeutic space in poverty-aware social work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2018, 48, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumer-Nevo, M. Poverty, social work, and radical incrementalism: Current developments of the poverty-aware paradigm. Soc. Policy Adm. 2022, 56, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Shlevin, S. Contextualized resistance: The mediating power of paradigmatic frameworks. Soc. Policy Adm. 2021, 55, 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, D.; Cantrell, A.; Booth, A. Rapid Evidence Review: Challenges to Implementing Digital and Data-Driven Technologies in Health and Social Care; The University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2021; Available online: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/175758/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Krumer-Nevo, M. Radical Hope: Poverty-Aware Practice for Social Work; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, R. Poverty; Polity Press: Bristol, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A. Poverty and shame—Messages for social work. Crit. Radic. Soc. Work 2015, 3, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, A.; Blumhardt, H.; ATD Fourth World. Giving poverty a voice: Families’ experiences of social work practice in a risk-averse child protection system. Fam. Relatsh. Soc. 2016, 5, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumer-Nevo, M.; Benjamin, O. Critical poverty knowledge: Contesting othering and social distancing. Curr. Sociol. 2010, 58, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Shlevin, S. Conceptualizing critical practice in social work: An integration of recognition and redistribution. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 2021. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saar-Heiman, Y.; Krumer-Nevo, M. Redistribution and recognition in social work practice: Lessons learned from providing material assistance in child protection settings. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2021, 91, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumer-Nevo, M.; Meir, A.; Weisberg-Nakash, N. Poverty-aware social work: Application of the paradigm in social service departments during 2014-2018. Soc. Secur. 2019, 106, 9–31. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bunting, L.; Montgomery, L.; Mooney, S.; MacDonald, M.; Coulter, S.; Hayes, D.; Davidson, G. Trauma informed child welfare systems—A rapid evidence review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ben-Rabi, D. Evaluation of the MAPA Pilot: Families Encounter Opportunities; Myers JDC Brookdale, Engelberg Center for Children and Youth: Jerusalem, Israel, 2019. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Dank, M. Noshmim Lerevaha: Evaluation Report; Effective Research for Impact: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 2018. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Dank, M. Noshmim Lerevaha: Second Evaluation Report; Effective Research for Impact: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 2022. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Elisar, R.; Shpitzer, H.; Leibovitz, N.; Dank, M.; Penso, A. Sustainability research summary report: Family First; Effective Research for Impact: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 2021. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Margolin, T. A Poverty-Aware Department: An Evaluation Study; Rashi Foundation, Research and Development: Ben-Shemen, Israel, 2022. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sabo-Lael, R.; Almog-Zaken, A.; Sorek, Y. Families on the Path to Growth: An Evaluation Study; Myers JDC Brookdale, Engelberg Center for Children and Youth: Jerusalem, Israel, 2020. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sorek, Y.; Almog-Zaken, A.; Konstantinov, W. An Optimal and Permanent Family: An Evaluation Study; Myers JDC Brookdale, Engelberg Center for Children and Youth: Jerusalem, Israel, 2021. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Turjeman, H.; Reuven, Y. Mifgash Initiative: Interim Report; Western Galilee College: Acre, Israel, 2018. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Gal, J.; Krumer-Nevo, M.; Madhala, S.; Yanay, G. Material Assistance to People Living in Poverty: A Historical Survey and Current Trends; Taub Center: Jerusalem, Israel, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Timor-Shlevin, S.; Benjamin, O. The struggle over the character of social services: Conceptualizing hybridity and power. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2022, 25, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Levi, A.; Malul, M.; Krumer-Nevo, M. Dynamics of change in poverty measures amongst social service users in Israel: A comparison of standard care and a Poverty-Aware Programme. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2022. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saar-Heiman, Y.; Nahari, M.; Krumer-Nevo, M. Critical social work in public social services: Poverty-aware organizational practices. J. Soc. Work. 2022. advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Benish, A.; Weiss-Gal, I. Social rights advocacy by social workers. Soc. Policy 2021, 113, 111–137. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Weiss-Dagan, S.; Krumer-Nevo, M. Poverty awareness: Development and validation of a new scale for examining attitudes regarding the aetiology and relational–symbolic aspects of poverty. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Levi, A.; Krumer-Nevo, M.; Malul, M. Service users’ perspectives of social treatment in social service departments in Israel: Differences between standard and poverty-aware treatments. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, E.; Krumer-Nevo, M. Poverty in Arab-Palestinian society in Israel: Social work perspectives before and during COVID-19. Int. Soc. Work. 2022. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Shlevin, S. The controlled arena of contested practices: Critical practice in Israel’s state social services. Br. J. Soc. Work 2021, 51, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Shlevin, S.; Benjamin, O. The tension between managerial and critical professional discourses in social work. J. Soc. Work 2021, 21, 951–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor-Shlevin, S. Between othering and recognition: In search for transformative practice at the street level. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 2022. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Freiberg, S. Client perspectives regarding the effects of a community-centred programme aimed at reducing poverty and Social exclusion. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 3697–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saar-Heiman, Y.; Lavie-Ajayi, M.; Krumer-Nevo, M. Poverty—Aware social work practice: Service users’ perspectives. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fook, J. Social Work: A Critical Approach to Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt, K. Surveillance and government of the welfare recipient. In Reading Foucault for Social Work; Chambon, A.S., Irving, A., Epstein, L., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, I. Poverty, Inequality and Social Work: The Impact of Neo-Liberalism and Austerity Politics on Welfare Provision; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Soss, J.; Fording, R.C.; Schram, S.F. Disciplining the poor: Neoliberal paternalism and the persistent power of race. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krumer-Nevo, M. The poverty challenge. In The Right to Good Welfare; Gal, J., Ed.; Menomadin Foundation: Herzliya, Israel, 2022; Available online: https://menomadinfoundation.com/he/%D7%94%D7%96%D7%9B%D7%95%D7%AA-%D7%9C%D7%A8%D7%95%D7%95%D7%97%D7%94-%D7%98%D7%95%D7%91%D7%94/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Garrett, P.M. Welfare Words: Critical Social Work and Social Policy; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Canvin, K.; Jones, C.; Marttila, A.; Burström, B.; Whitehead, M. Can I risk using public services? Perceived consequences of seeking help and health care among households living in poverty: Qualitative study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Program | Organizational Context | Target Population | No. of Local Authorities in Which the Program Operated | No. of Families that Participated | No. of Social Workers Employed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Casework for Social Change | Fieldwork training program for BA students | Families living in persistent, extreme poverty and branded as “uncooperative” in past attempts to reach out to them in more traditional practice | 1 | 250 | 72 (students) |

| P2 | Mapa | Ministry of Welfare and Social Affairs (MWSA)–Family services | Families living in persistent, extreme poverty and branded as “uncooperative” in past attempts to reach out to them in more traditional practice | 10 | 150 | 50 |

| P3 | Families First | MWSA–Family services | Families living in poverty with parents who are not coping with mental illness, delinquency, or active addiction | 113 | 14,000 | 770 |

| P4 | Families on the Path to Growth | MWSA–Child protection services | Families with children aged 0–18 identified as being at high risk of child maltreatment—on the verge of removal or reunification | 17 | 330 | |

| P5 | Mifgash | MWSA–Child protection services | Families in which children are identified as suffering from neglect | 12 | 303 |

| Study | No. in Ref. List | Publication Outlet | Language | Research Site | Method | Data Collection Points | Sample | Study Focus | Findings’ Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | Social Security peer-reviewed journal | Hebrew | P3 | Qualitative: semi-structured interviews | 1 T | 40 frontline social workers | Active actualization role | Impact on SW |

| [26] | Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel | English | P3 | Quantitative: analysis of administrative data | 2 Ts | 5700 service users | Material assistance | Impact on SW+ SU outcomes |

| [18] | Myers JDC Brookdale center for applied social research | Hebrew | P2 | Mixed methods Quantitative method: questionnaire Qualitative method: focus group interviews | 2 Ts | Quantitative sample: 66 service users Qualitative sample: 5 service users and 33 practitioners | Program evaluation | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [31] | British Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | PAP training courses | Quantitative method: questionnaires | 2 Ts | Sample: 92 social workers and 34 social work students | Training | Impact on SW |

| [32] | Health and Social Care in the Community peer-reviewed journal | English | P2 and P3 | Mixed methods Quantitative methods: questionnaire Qualitative methods: structured interviews | 1 T | 235 service users | Program evaluation | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [28] | British Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P3 | Quantitative methods: questionnaire | 2 Ts | 159 service users | Program evaluation | SU outcomes |

| [33] | International Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P3 | Qualitative method: analysis of supervision protocols | 14 social workers | Poverty-aware social work in Arab-Palestinian society | Impact on SW | |

| [4] | Social Security peer-reviewed journal | Hebrew | P2 and P3 | Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 1 T | 41 social work practitioners and managers | Policy implementation | Impact on SW |

| [34] | British Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P2 and P3 | Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 1 T | 25 social workers | Poverty-aware practice | Impact on SW |

| [7] | Social Policy and Administration peer-reviewed journal | English | P2 and P3 | Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 1 T | 16 senior managers and policymakers | Policy implementation | Impact on SW |

| [35] | Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P2 and P3 | Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 1 T | 14 social workers | Poverty-aware practice | Impact on SW |

| [27] | European Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P2 and P3 | Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 1 T | 16 senior managers and policymakers | Policy implementation | Impact on SW |

| [36] | European Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P2 and P3 | Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 1 T | 25 social work practitioners and managers | Poverty-aware practice | Impact on SW |

| [37] | British Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P3 | Qualitative method: semi-structured interviews | 1 T | 13 service users | Community practice | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [23] | Myers JDC Brookdale center for applied social research | Hebrew | P4 | Mixed methods Quantitative methods–randomized controlled tests and questionnaires Qualitative methods–semi-structured interviews and case studies | 2 Ts | Quantitative sample: 224 service users and 100 social workers Qualitative sample: 8 service users and 17 social workers | Program evaluation | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [24] | Myers JDC Brookdale center for applied social research | Hebrew | P4 | Mixed methods. Quantitative methods: administrative data analysis Qualitative methods: case studies and focus groups | 2 Ts | Quantitative sample: 44 service users Qualitative sample: 8 service users and 24 social workers | Program evaluation | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [25] | Western Galilee College academic institution | Hebrew | P5 | Mixed methods Quantitative methods: questionnaires Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews and focus groups | 4 Ts | Quantitative sample: 140 practitioners and 175 service users. Qualitative sample: 22 service users and 73 practitioners and policymakers | Program evaluation | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [19] | Effective Research for Impact research institute | Hebrew | P3 | Mixed methods. Quantitative methods:questionnaires and administrative data Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 2 Ts | Quantitative sample: 346 families and 396 social workers Qualitative sample: 19 service users and 99 practitioners and policymakers from senior management | Program evaluation | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [20] | Effective Research for Impact research institute | Hebrew | P3 | Quantitative methods: questionnaires | 2 Ts | 2029 families | Program evaluation | SU outcomes |

| [22] | Rashi Foundation research and development | Hebrew | P2, P3, P4, P5 | Mixed methods. Quantitative methods: questionnaires Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews and focus groups | 1 T | Quantitative sample: 601 professionals and 1044 service users Qualitative sample: 14 semi-structured interviews and 3 focus groups | Programs evaluations | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [38] | Child and Family Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P1 | Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 3 Ts | 9 service users | Program evaluation | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [5] | British Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P1 | Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 3 Ts | 9 service users | Working in a real-life context | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [29] | Journal of Social Work peer-reviewed journal | English | P2 and P3 | Qualitative methods: ethnographic observations and participatory workshops | 3 Ts | 25 social workers and 10 service users | PAP organizational practices | Impact on SW + SU outcomes |

| [15] | American Journal of Psychotherapy peer-reviewed journal | English | P4 | Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 1 T | 20 interviews with SW | Material assistance | Impact on SW |

| [21] | Effective Research for Impact research institute | Hebrew | P3 | Mixed methods. Quantitative methods: questionnaires Qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews | 3Ts | Quantitative sample: 290 service users Qualitative sample: 11 semi-structured interviews with families | Program evaluation | SU outcomes |

| Total | Publication | Language | Research site | Method | Sample | Study focus | Finding’s domain | ||

| 15 publications written by authors, among them–14 peer-reviewed, 1 research report | * 16 peer-reviewed journals * 9 research reports | * English: 15 * Hebrew: 10 | * P1: 2 publications * P2: 11 publications * P3: 17 * P4: 4 * P5: 2 * Training programs:1 | * Mixed methods: 8 * Quantitative methods: 3 * Qualitative methods: 14 | * 1 T: 11 * 2 Ts: 10 * 3 Ts: 3 *4 Ts: 1 | * Quantitative sample: 4612 service users and 1363 social workers * Qualitative sample: 420 service users and 424 social workers and policymakers * Administrative data regarding 5700 service users These numbers are approximate (some studies may overlap) | * Evaluation–10 Direct practice and implementation–8 policy and organizational implementation–4 Training–1 Arab society–1 | Impact on SW–10 Impact on SU outcomes–3 Impact on SW and SU outcomes–12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Timor-Shlevin, S.; Saar-Heiman, Y.; Krumer-Nevo, M. Poverty-Aware Programs in Social Service Departments in Israel: A Rapid Evidence Review of Outcomes for Service Users and Social Work Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010889

Timor-Shlevin S, Saar-Heiman Y, Krumer-Nevo M. Poverty-Aware Programs in Social Service Departments in Israel: A Rapid Evidence Review of Outcomes for Service Users and Social Work Practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010889

Chicago/Turabian StyleTimor-Shlevin, Shachar, Yuval Saar-Heiman, and Michal Krumer-Nevo. 2023. "Poverty-Aware Programs in Social Service Departments in Israel: A Rapid Evidence Review of Outcomes for Service Users and Social Work Practice" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010889

APA StyleTimor-Shlevin, S., Saar-Heiman, Y., & Krumer-Nevo, M. (2023). Poverty-Aware Programs in Social Service Departments in Israel: A Rapid Evidence Review of Outcomes for Service Users and Social Work Practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010889