Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Coupling and Coordination of Cultural Tourism and Objective Well-Being in Western China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Data Resources

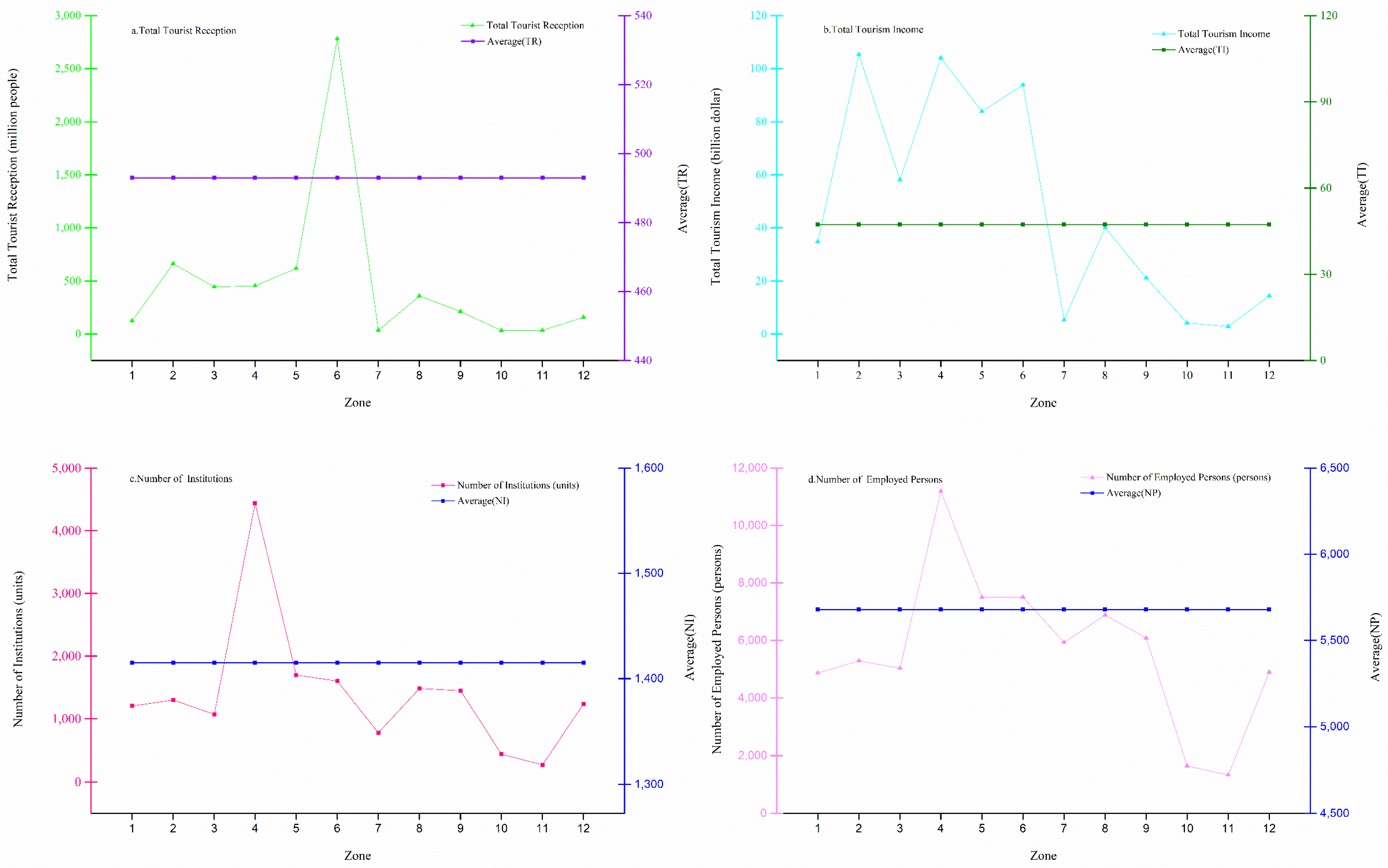

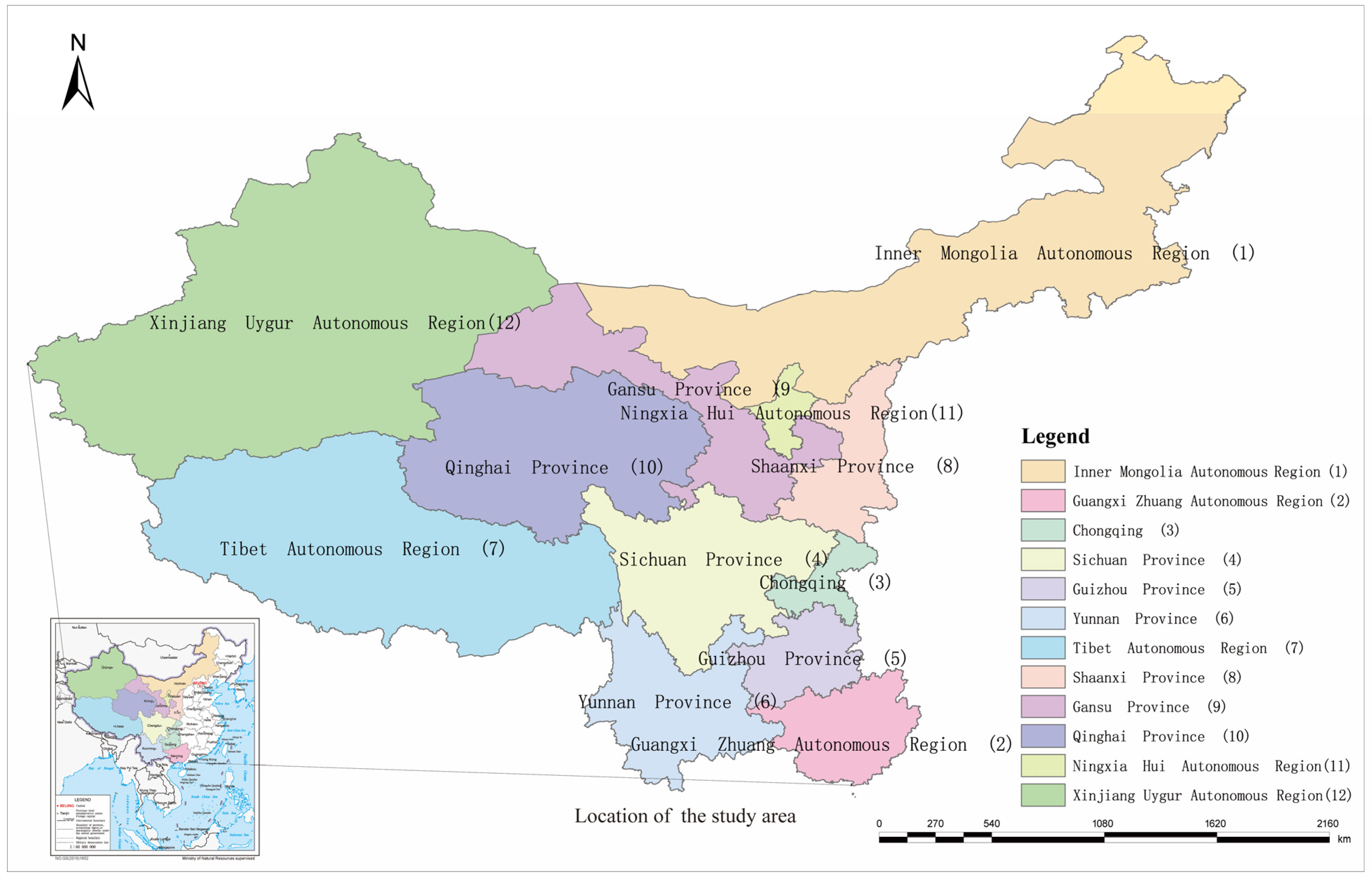

2.1. Study Area

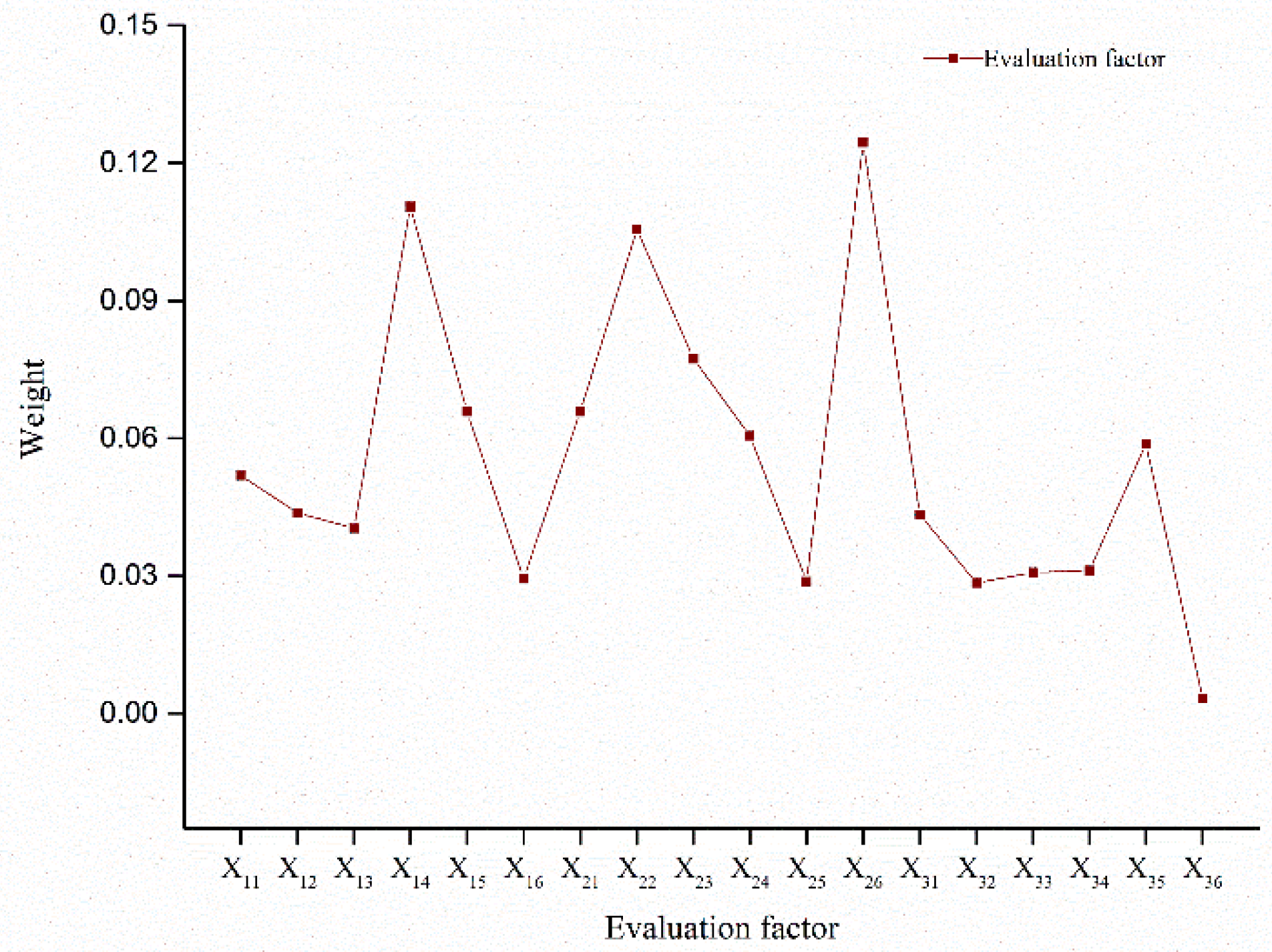

2.2. Building an Indicator System and Data Sources

3. Methods

3.1. Entropy Weight Method

- (1)

- Standardized processing of indicators:

- (2)

- Determine the metric weight:

- (3)

- Calculate the entropy value of j:

- (4)

- Calculate the information utility value of item j:

- (5)

- Calculate the weight of each indicator (Figure 1):

3.2. Coupling Coordination Models

3.3. Spatial Variability Analysis

3.3.1. Thiel Index

3.3.2. Standard Deviation and Coefficient of Variation

4. Results

4.1. Comprehensive Evaluation of Time Series Change Analysis

4.2. Coupled Coordinated Timing Change Analysis

4.3. Spatial Differentiation Feature Changes of Coupling Coordinates

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, X.X. Research on cultural tourism resources in Shanxi Province. Hum. Geogr. 2004, 5, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J. The connotation and development strategy of China’s marine cultural industry. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2020, 4, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Tang, C.C.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Long, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Gan, M.; et al. Research on tourism resources in the new era: Protection, utilization and innovative development: Comments of young tourism geographers. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 992–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.R. Exploration on Digital Transmission of Cultural Tourism from the Perspective of Meta Universe. J. Lover 2022, 9, 60–62. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.Q.; lv, T. Virtual tourism: The impact of online comments on experience of tourism live broadcast based on eye movement. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 86–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X. Digital Tourism—A New Model of Tourism Economic Development in China. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Research on the transformation path of China’s cultural tourism industry: A perspective of media ecological change. J. Shandong Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2021, 6, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, B.; Li, J. Price Mechanism and Regulation of Cultural Tourism Products. Soc. Sci. 2016, 3, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.Y. Innovative Development Strategy of Regional Digital Cultural Tourism under the Background of Internet. Soc. Sci. 2021, 9, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.L. Research on the Mechanism and Policy Optimization of the Integration of Culture and Tourism to Promote Common Prosperity. Soc. Sci. Guangxi 2022, 9, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.F.; Ge, J.L.; Chu, S.V. Theoretical connotation and scientific problems of tourism resources under the background of national strategy. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 1511–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.L.; Yu, H. The Coupling Development of Tourism and Urbanization in Daxiangxi Area. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 36, 204–208+141. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Y.; Liang, X.P.; Yu, T.; Ruan, S.J.; Fan, R. Research on the Integration of Cultural Tourism Industry Driven by Digital Economy in the Context of COVID-19—Based on the Data of 31 Chinese Provinces. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 780476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, G.J. Comparative study of cultural tourism industry in Korea and China-Focusing on local cultural tourism products. J. Digit. Converg. 2020, 18, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.G.; Ding, P.Y.; Packer, J. Tourism Research in China: Understanding the Unique Cultural Contexts and Complexities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, M.M.; Shen, M.H.; Xie, H.M. Cultural diffusion and international inbound tourism: Evidence from China. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 884–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, G.M.; Li, L.Y. The Coupling Coordination Degree and Spatial Correlation Analysis on Integrational Development of Tourism Industry and Cultural Industry in China. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 36, 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.J.; Tong, L.; Zhou, H.F.; Luo, J.Q. Subjective Well-being Measurement and Optimization Strategy of Farmers in Zhejiang Province from the Perspective of Common Prosperity. J. Zhejiang Agric. Sci. 2022, 63, 2228–2233. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet, L. Cultural Tourism. Handbook of Cultural Economics, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.M.; Yang, X.Y.; Fu, S.H.; Huan, T.C. Exploring the influence of tourists’ happiness on revisit intention in the context of Traditional Chinese Medicine cultural tourism. Tour. Manag. 2022, 94, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korunovski, S.; Marinoski, N. Cultural tourism in Ohrid as a selective form of tourism development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 44, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fitch, R.A.; Mueller, J.M.; Ruiz, R.; Rousse, W. Recreation Matters: Estimating Millennials’ Preferences for Native American Cultural Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Qiu, Z.Y. Urban Sustainable Development Empowered by Cultural and Tourism Industries: Using Zhenjiang as an Example. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y. Research on the Current Situation and Promotion Path of Cultural Tourism Competitiveness—A Case Study of Henan. Product. Res. 2011, 10, 171–173. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Tkatch, R.; Martin, D.; MacLeod, S.; Sandy, L.; Yeh, C. Resilient Aging: Psychological Well-Being and Social Well-Being as Targets for the Promotion of Healthy Aging. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.; Shaw, B.; Guntzberger, M.; Aubel, J.; Coulibaly, M.; Igras, S. Transforming social norms to improve girl-child health and well-being: A realist evaluation of the Girls’ Holistic Development program in rural Senegal. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Diekmann, A. Tourism and wellbeing. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Johnson, S. The happiness factor in Tourism: Subjective Well-being and social tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.J.; Swanson, S.R. Perceived corporate social responsibility’s impact on the well-being and supportive green behaviors of hotel employees: The mediating role of the employee-corporate relationship. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Ali, F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naserisafavi, N.; Coyne, T.; Melo, Z.; de Lourdes Melo Zurita, M.; Zhang, K.F.; Prodanovic, V. Community values on governing urban water nature-based solutions in Sydney, Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 116063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Yuan, L.; Chen, C.J.; Huang, Q.Y. Research progress and prospect of the interrelationship between ecosystem services and human well-being in the context of coupled human and natural system. Prog. Geogr. 2021, 40, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.S.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Rigolon, A.; Larson, L.R.; Taff, D.; Labib, S.M.; Benfield, J.; Yuan, S.; McAnirlin, O.; Hatami, N.; et al. Beyond “bluespace” and “greenspace”: A narrative review of possible health benefits from exposure to other natural landscapes. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 856 Pt 2, 159292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, C.U. Satisfaction and Constraints on Leisure Activities Participation among the Leisure Facilities User in Korea. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 28, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer, B.P.; Andrews, J.L.; Orben, A.; Speyer, L.G.; Blakemore, S.J. The relationship between perceived income inequality, adverse mental health and interpersonal difficulties in UK adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.Y.; Kao, T.S.A.; Robbins, L.B.; Wahman, C.L. Family lifestyle is related to low-income preschoolers’ emotional well-being during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, Y. An Analysis on the Economic Structures of Low-income Households: Policy Suggestion for Their Economic Well-being. J. Consum. Cult. 2012, 15, 213–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, M.; Herke, M.; Richter, M.; Diehl, K.; Hoffmann, S.; Pischke, C.R.; Dragano, N. Young people’s health and well-being during the school-to-work transition: A prospective cohort study comparing post-secondary pathways. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerson, M.A.; Reeve, B.B.; Gilkey, M.B.; Elmore, S.N.C.; Hayes, S.; Bradley, C.J.; Troester, M.A. Job loss, return to work, and multidimensional well-being after breast cancer treatment in working-age Black and White women. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia-Lancheros, C.; Alfayumi-Zeadna, S.; Lachaud, J.; O’Campo, P.; Gogosis, E.; Da Silva, G.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Hwang, S.W.; Thulien, N. Differential impacts of COVID-19 and associated responses on the health, social well-being and food security of users of supportive social and health programs during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e4332–e4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, U.; Robertson, K.; Aitken, R. Experience, Emotion, and Eudaimonia: A Consideration of Tourist Experiences and Well-being. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banarsyadhimi, U.R.A.M.F.; Dargusch, P.; Kurniawan, F. Assessing the Impact of Marine Tourism and Protection on Cultural Ecosystem Services Using Integrated Approach: A Case Study of Gili Matra Islands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Taheri, B. Assessing the Mediating Role of Residents’ Perceptions toward Tourism Development. J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.G.; Zhang, H.M.; He, Y.M.; Ji, L.L. Social Well-being Effect of Integrated Development of Culture and Tourism: Logical Interpretation, Measurement and Mechanism Framework. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.L.; Liu, J.L. Cognition, Motivation and Development Direction of Cultural Tourism Integration. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2019, 12, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y. Reflection on the Intrinsic Value of the Integration of Culture and Tourism. Frontiers 2019, 11, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.M. 2022 Western Cultural Tourism Development Report. New West 2022, 4, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.F. Study on the Coupling and Coordination Relationship Between Tourism Resource Development Intensity and Ecological Capacity: A Case Study of in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2021, 30, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.Y.; Mu, X.Q.; Ming, Q.Z.; Ding, Z.S. Spatial and temporal differentiation characteristics of transportation service function and tourism intensity coordination: A case study of Yunnan province. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 1425–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.L.; Li, Z. Study Tour Service of Public Cultural Service Institutions: Significance, Status Quo and Strategy. Libr. J. 2022, 41, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, S.N.; Chen, S.X. The Dynamic Mechanism Analysis of Institutional Changes in Chinese Art Performance Group: From the Perspective of the Historical Institutionalism. Humanit. Soc. Sci. J. Hainan Univ. 2021, 39, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.W.; Tian, Y.; Cui, J.X.; Luo, J.; Zeng, J.X.; Han, Y. Identification of Tourism Spatial Structure and Measurement of Tourism Spatial Accessibility in Hubei Province. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 37, 208–217. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Ying, T.T.; Liu, T. Distribution characteristics and influencing factors of tourism industry’s spatial agglomeration—Taking Guangdong Province as an example. World Reg. Stud. 2016, 25, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. Research on Regional Differences and Polarization of China’s Health Construction Level from a Multi-dimensional Perspective: Based on the Strategic Goal of “Healthy China 2030”. Popul. Econ. 2022, 5, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.M.; Yao, L.L.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, D.; Lin, Y.M. Estimate Well-Being of Urban and Rural Residents in the Yellow River Basin and Its Spatial-Temporal Evolution. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 38, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Sun, Z.C. The Development of Western New-type Urbanization Level Evaluation Based on Entropy Method. Econ. Probl. 2015, 3, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Jiao, H.F.; Ye, L. Spatio-temporal Characteristics of Coordinated Development Between Tourism Economy and Transportation: A Case of International Culture and Tourism Demonstration Area in South Anhui Province. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2019, 39, 1822–1829. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, G.M.; Tang, Y.B.; Pan, Y.; Mao, Y.Q. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Spatial Difference of Tourism-Ecology-Urbanization Coupling Coordination in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, T. Spatio-temporal coupling analysis of the dominance of inbound tourism flow and tourism economic efficiency in China. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 36, 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, H.Q.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z.F. Temporal and Spatial Coupling Coordination of Green Utilization Efficiency of Tourism Resources and New Urbanization in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Yong, M. Analysis of Regional Tourism Economic Differences Based on Theil Index by Taking the Example Area of the South Anhui International Cultural Tourism as an Example. J. Tangshan Norm. Univ. 2019, 41, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Cao, W.N.; Yan, S.N. Spatial Heterogeneity of the impact of tourism development on Urban-rural income gap in China-Based on Multi-scale Geographically Weighted Regression Model (MGWR). J. China Univ. Geosci. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 22, 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.C.; Liang, X.C.; Song, X.; Zhao, Y. Spatial Network Structure and Formation Mechanism of Cultural Tourism Industry Integrated with High-quality Development. Stat. Decis. 2022, 38, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Q. Research on Multidimensional Innovation of Integrated Development of Cultural Tourism from the Global Perspective. J. Chizhou Univ. 2019, 33, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. Research on Cross Regional Collaborative Development of Cultural Tourism in Chengdu: From the Perspective of Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle. J. Chengdu Adm. Inst. 2022, 2, 106–115+120. [Google Scholar]

| First Index | Second Index | Evaluation Factor | Factor | Unit | P/N * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT system | Supply capacity | Number of 5A tourist attractions | X11 | Number | + |

| Number of star tourist hotels | X12 | Number | + | ||

| Number of travel agencies | X13 | Number | + | ||

| Number of artistic performance groups | X14 | Number | + | ||

| Number of museums | X15 | Number | + | ||

| Number of cultural centers | X16 | Number | + | ||

| Demand capability | Per capita tourism consumption of domestic tourists | X21 | USD/person | + | |

| Per capita tourism consumption of inbound tourists | X22 | USD/person | + | ||

| Total library circulation | X23 | 10,000 person-times | + | ||

| Total visitors to museums | X24 | 10,000 person-times | + | ||

| Domestic art performance attendance | X25 | 10,000 person-times | + | ||

| Cultural market institutions operating income | X26 | USD | + | ||

| OWB system | Comprehensive consumption ability | Per capita disposable income | X31 | USD/person | + |

| Health service capability | Healthcare personnel per thousand population | X32 | Number of persons | + | |

| Medical institution beds per thousand population | X33 | Number of medical beds | + | ||

| Environmental service ability | Per capita public green space area | X34 | m2 | + | |

| Safety assurance ability | Public security expenditure | X35 | Billion USD | + | |

| Traffic accident death and injury rates | X36 | Rate | − |

| Zone | 5A Tourist Attractions | Star Tourist Hotels | Number of Travel Agencies | Number of Artistic Performance Groups | Museums | Cultural Centers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region | 6 | 205 | 1202 | 204 | 172 | 117 |

| 6.19% | 6.25% | 13.08% | 5.05% | 10.54% | 9.61% | |

| Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region | 6 | 444 | 881 | 78 | 142 | 116 |

| 6.19% | 13.53% | 9.59% | 1.93% | 8.70% | 9.52% | |

| Chongqing | 10 | 163 | 714 | 1265 | 105 | 43 |

| 10.31% | 4.97% | 7.77% | 31.29% | 6.43% | 3.53% | |

| Sichuan Province | 15 | 356 | 1336 | 725 | 258 | 207 |

| 15.46% | 10.85% | 14.54% | 17.93% | 15.81% | 17.00% | |

| Guizhou Province | 8 | 231 | 665 | 200 | 92 | 100 |

| 8.25% | 7.04% | 7.24% | 4.95% | 5.64% | 8.21% | |

| Yunnan Province | 9 | 415 | 1105 | 270 | 161 | 149 |

| 9.28% | 12.65% | 12.02% | 6.68% | 9.87% | 12.23% | |

| Tibet Autonomous Region | 5 | 165 | 310 | 87 | 8 | 81 |

| 5.15% | 5.03% | 3.37% | 2.15% | 0.49% | 6.65% | |

| Shaanxi Province | 11 | 325 | 862 | 591 | 309 | 117 |

| 11.34% | 9.91% | 9.38% | 14.62% | 18.93% | 9.61% | |

| Gansu province | 5 | 384 | 780 | 347 | 226 | 104 |

| 5.15% | 11.70% | 8.49% | 8.58% | 13.85% | 8.54% | |

| Qinghai Province | 4 | 207 | 515 | 122 | 24 | 50 |

| 4.12% | 6.31% | 5.60% | 3.02% | 1.47% | 4.11% | |

| Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region | 4 | 89 | 164 | 30 | 54 | 27 |

| 4.12% | 2.71% | 1.78% | 0.74% | 3.31% | 2.22% | |

| Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | 14 | 297 | 657 | 124 | 81 | 107 |

| 14.43% | 9.05% | 7.15% | 3.07% | 4.96% | 8.78% | |

| Western China | 97 | 3282 | 9192 | 4044 | 1633 | 1219 |

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Stage of Development | Rank of Harmony Degree | Concrete Types | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinated development [0.6, 1] | Better coordination [0.9, 1] Well coordinated [0.8, 0.9) Intermediate coordination [0.7, 0.8) Lower coordination [0.6, 0.7) | Lagging CT system Lagging OWB system Synchronized CT and OWB systems | U2-U1 ≥ 0.1 U1-U2 ≥ 0.1 U1 < 0.1 and U2 < 0.1 |

| Transitional development [0.4, 0.6) | Barely coordinated [0.5, 0.6) On the verge of imbalance [0.4, 0.5) | Lagging CT system Lagging OWB system Synchronized CT and OWB systems | U2-U1 ≥ 0.1 U1-U2 ≥ 0.1 U1 < 0.1 and U2 < 0.1 |

| Dysfunctional development [0.0, 0.4) | Mild disorder [0.3, 0.4) Moderate outrage [0.2, 0.3) Severe dysregulation [0.1, 0.2) Extreme dysregulation [0, 0.1) | Lagging CT system Lagging OWB system Synchronized CT and OWB systems | U2-U1 ≥ 0.1 U1-U2 ≥ 0.1 U1 < 0.1 and U2 < 0.1 |

| 2007–2020 | CT System | OWB System | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in Magnitude | Average Annual Growth Rate | Increase in Magnitude | Average Annual Growth Rate | |

| Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region | 107.73% | 5.78% | 289.10% | 11.02% |

| Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region | 53.95% | 3.37% | 464.02% | 14.23% |

| Chongqing | 262.89% | 10.42% | 667.18% | 16.97% |

| Sichuan Province | 108.07% | 5.80% | 466.64% | 14.27% |

| Guizhou Province | 202.17% | 8.88% | 1751.25% | 25.17% |

| Yunnan Province | 66.07% | 3.98% | 524.46% | 15.13% |

| Tibet Autonomous Region | 251.45% | 10.15% | 721.13% | 17.58% |

| Shaanxi Province | 131.82% | 6.68% | 383.46% | 12.89% |

| Gansu province | 134.25% | 6.77% | 603.99% | 16.20% |

| Qinghai Province | 215.56% | 9.24% | 359.38% | 12.44% |

| Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region | 132.54% | 6.71% | 293.29% | 11.11% |

| Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region | 30.99% | 2.10% | 269.89% | 10.59% |

| Stage of Development | Year | C | D | Specific Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysfunctional development | 2007 | 0.9940 | 0.2611 | CT and OWB systems synchronized in moderate imbalance |

| 2008 | 0.9865 | 0.3338 | CT and OWB systems synchronized in mild disorder | |

| Transitional development | 2009 | 0.9978 | 0.4292 | CT and OWB systems synchronized on the verge of imbalance |

| 2010 | 0.9710 | 0.4703 | Lagging CT system on the verge of imbalance | |

| 2011 | 0.9786 | 0.5249 | Lagging CT system, barely coordinated | |

| Coordinated development | 2012 | 0.9926 | 0.6058 | CT and OWB systems synchronized in low coordination |

| 2013 | 0.9997 | 0.6964 | CT and OWB systems synchronized in low coordination | |

| 2014 | 0.9974 | 0.7199 | CT and OWB systems synchronized in intermediate coordination | |

| 2015 | 0.9991 | 0.7670 | CT and OWB systems synchronized in intermediate coordination | |

| 2016 | 0.9995 | 0.8141 | CT and OWB systems synchronized and well coordinated | |

| 2017 | 1.0000 | 0.8746 | CT and OWB systems synchronized and well coordinated | |

| 2018 | 0.9997 | 0.8966 | CT and OWB systems synchronized and well coordinated | |

| 2019 | 1.0000 | 0.9260 | CT and OWB systems synchronized in better coordination | |

| 2020 | 0.9827 | 0.8515 | Lagging CT system, well coordinated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pu, L.; Chen, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, H. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Coupling and Coordination of Cultural Tourism and Objective Well-Being in Western China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010650

Pu L, Chen X, Jiang L, Zhang H. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Coupling and Coordination of Cultural Tourism and Objective Well-Being in Western China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010650

Chicago/Turabian StylePu, Lili, Xingpeng Chen, Li Jiang, and Hang Zhang. 2023. "Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Coupling and Coordination of Cultural Tourism and Objective Well-Being in Western China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010650

APA StylePu, L., Chen, X., Jiang, L., & Zhang, H. (2023). Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Coupling and Coordination of Cultural Tourism and Objective Well-Being in Western China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010650