Why do Social Workers Leave? A Moderated Mediation of Professionalism, Job Satisfaction, and Managerialism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Model and Hypotheses

2.1. Professionalism and Turnover Intention

2.2. The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction

2.3. The Moderating Role of Managerialism

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Biases

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

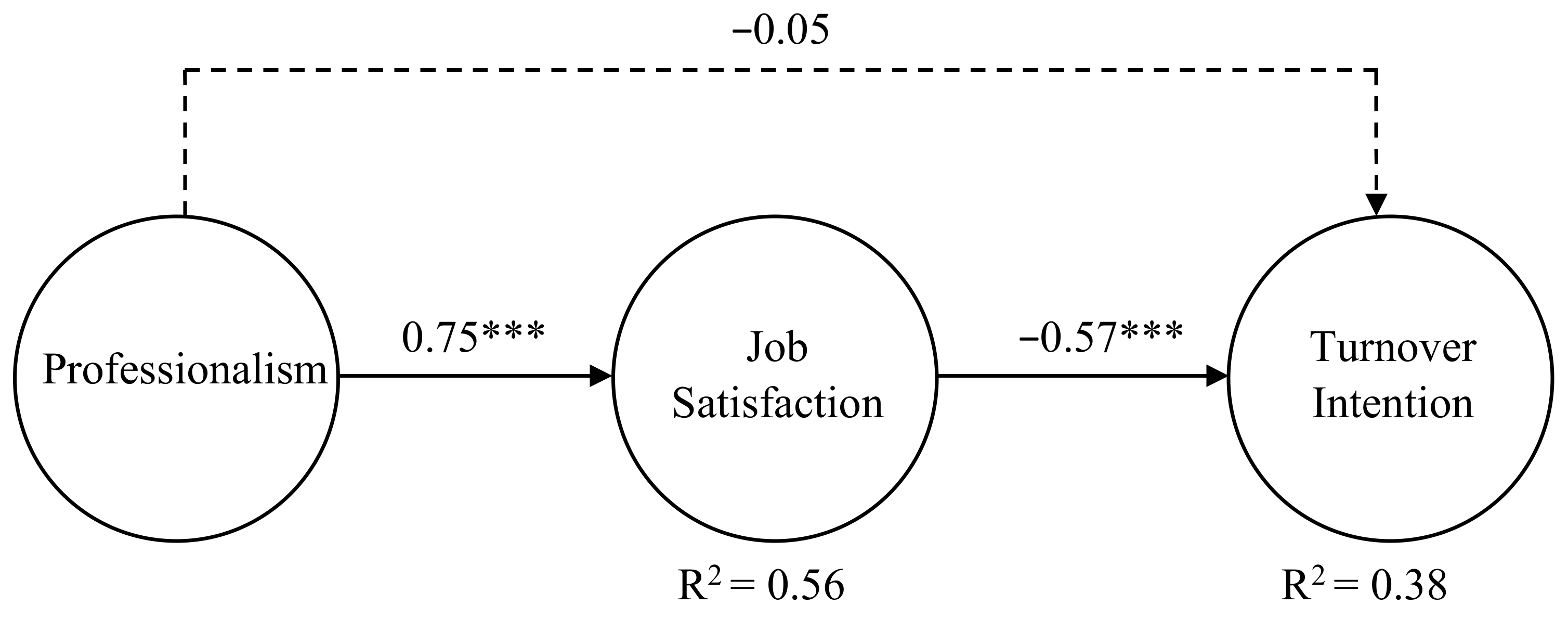

4.4. Test of Structural Model

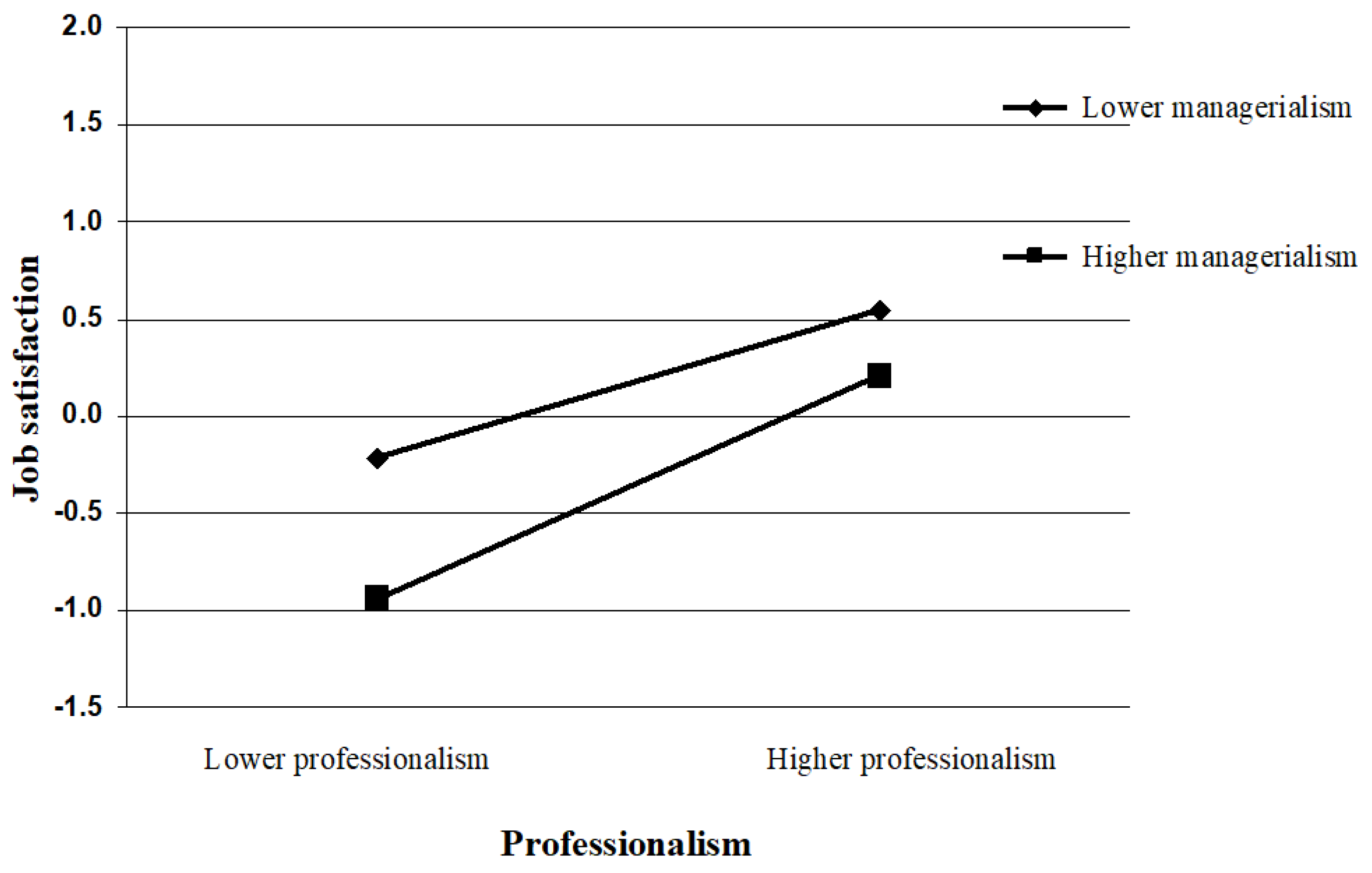

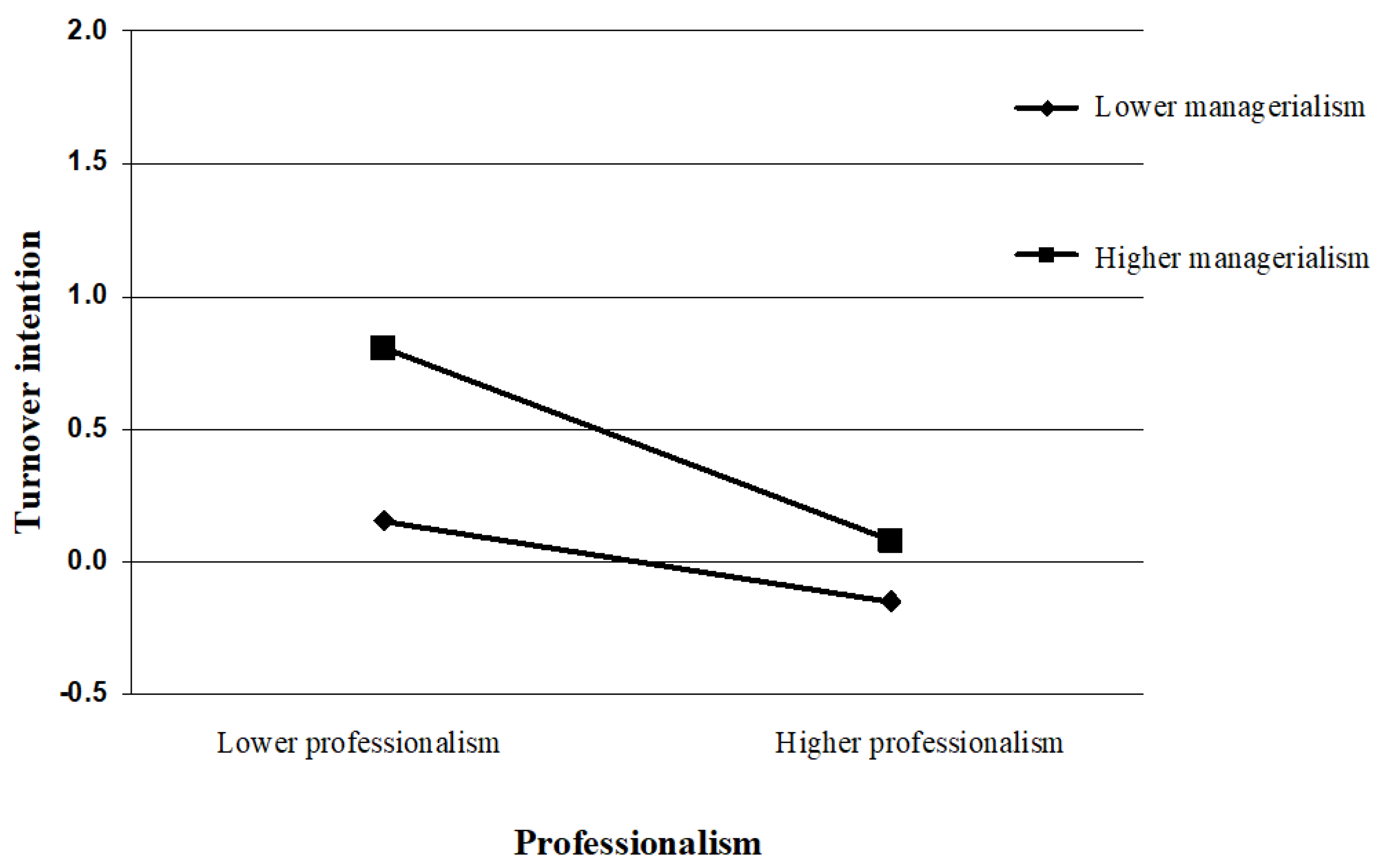

4.5. Test of Moderating Mediation Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Overall Model

5.2. The Moderating Effect of Managerialism

5.3. Limitations and Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moynihan, D.P.; Pandey, S.K. The ties that bind: Social networks, person-organization value fit, and turnover intention. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.T. Some Social Workers in Shenzhen Left to Dong Guan and Hui Zhou: The Turnover Rate Has Exceeded 22% Last Year. Nanfang Daily. 2021. Available online: http://sz.southcn.com/content/2015-01/30/content_117407995.htm (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Tang, Y.; Chen, H.Y.; Ye, F.R.; Luo, P. Research on social workers’ job burnout, organizational environment and professional identity. J. Soc. Work 2021, 4, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.X.; Dong, Z.Y.; Chen, E.Z. Research on the status quo of professional identity, job satisfaction and turnover intention of medical social workers in Shanghai. China Soc. Work 2022, 18, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts, S.; Schaufeli, W.; De Jonge, J. Burnout and intention to leave among mental health-care professionals: A social psychological approach. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 17, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.Y.; Shaw, J.D. Turnover rates and organizational performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 268–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hao, W.Q.; Song, W.Z. Transformational leadership, professional autonomy and professional development of social workers. Soc. Constr. 2020, 7, 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hom, P.W.; Lee, T.W.; Shaw, J.D.; Hausknecht, J.P. One hundred years of employee turnover theory and research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, J.C.; McCain, B.E. Satisfaction, commitment and professionalism of newly employed nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 1987, 19, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynd, C.A. Current factors contributing to professionalism in nursing. J. Prof. Nurs. 2003, 19, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R. Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manojlovich, M.; Ketefian, S. The effects of organizational culture on nursing professionalism: Implications for health resource planning. Can. J. Nurs. Res. Arch. 2002, 33, 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, J.A.; Lichtenstein, R.; Oh, H.J.; Ullman, E. A causal model of voluntary turnover among nursing personnel in long-term psychiatric settings. Res. Nurs. Health 1998, 21, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, W.H.; Robbins, T.; Miller, J.; Summers, T.P. Effects of procedural and distributive justice on factors predictive of turnover. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 1998, 13, 611–632. [Google Scholar]

- Duphily, N.H. Simulation education: A primer for professionalism. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2014, 9, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, G.E.; Cameron, J.E. Multiple dimensions of organizational identification and commitment as predictors of turnover intentions and psychological well-being. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 2005, 37, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evetts, J. A new professionalism? Challenges and opportunities. Curr. Sociol. 2011, 59, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job-satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover—Path analysis based on metaanalytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreilly, C.A.; Caldwell, D.F. The commitment and job tenure of new employees—Some evidence of post-decisional justification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, M.E.M.; Levin, A.; Nissly, J.A.; Lane, C.J. Why do they leave? Modeling child welfare workers’ turnover intentions. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2006, 28, 548–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanez, J.A.; Jahanshahi, A.A.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Li, J.Z.; Zhang, S.X. Anxiety, Distress, and Turnover Intention of Healthcare Workers in Peru by Their Distance to the Epicenter during the COVID-19 Crisis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1614–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, N.; Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. Teacher burnout and turnover intent. Aust. Educ. Res. 2020, 47, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Stoner, M. Burnout and turnover intention among social workers: Effects of role stress, job autonomy and social support. Adm. Soc. Work 2008, 32, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, P.; Phungsoonthorn, T. The effect of cultural intelligence of top management on pro-diversity work climate and work attitudes of Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2022, 41, 760–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, S.; Hisar, F. The influence of the professionalism behaviour of nurses working in health institutions on job satisfaction. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.J.; Xie, W.X.; Wang, X.Y.; Qu, J.L.; Zhou, T.; Li, Y.N.; Mao, X.E.; Hou, P.; Liu, Y.B. Impact of innovative education on the professionalism of undergraduate nursing students in China. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 98, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, T.T.F. Social work professionalism in self-help organizations. Int. Soc. Work 2010, 53, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kao, D. A meta-analysis of turnover intention predictors among US child welfare workers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 47, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.D.; Zhang, R.Y. Deconstructing news feelings: A study of journalist’s altruism, social value perception and organizational commitment. Shanghai J. Rev. 2019, 10, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.B. Social work gives full play to professional advantages, professional feelings and professional rationality to intervene in social crisis events. J. Soc. Work 2020, 1, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.F.; Zeng, S.C. Re-discussion of social feelings: The relationship between social workers’ social value perception and turnover intention. J. East China Univ. Sci. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 3, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Johnco, C.; Salloum, A.; Olson, K.R.; Edwards, L.M. Child welfare workers’ perspectives on contributing factors to retention and turnover: Recommendations for improvement. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 47, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.I.; Lou, F.; Han, S.S.; Cao, F.; Kim, W.O.; Li, P. Professionalism: The major factor influencing job satisfaction among Korean and Chinese nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2009, 56, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manlove, E.E.; Guzell, J.R. Intention to leave, anticipated reasons for leaving, and 12-month turnover of child care center staff. Early Child. Res. Q. 1997, 12, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.P. Nurse retention and satisfaction in Ecuador: Implications for nursing administration. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellman, C.M. Job satisfaction and intent to leave. J. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 137, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Eisen, S.V.; Sederer, L.I.; Yamada, O.; Tachimori, H. Factors affecting psychiatric nurses’ intention to leave their current job. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Cluse-Tolar, T.; Pasupuleti, S.; Prior, M.; Allen, R.I. A test of a turnover intent model. Adm. Soc. Work 2012, 36, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, U.; Schinke, S.P. Organizational and individual factors influencing job satisfaction and burnout of mental health workers. Soc. Work Health Care 1998, 28, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snizek, W.E. Hall’s professionalism scale: An empirical reassessment. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1972, 37, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.H. Professionalization and bureaucratization. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1968, 33, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F. One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.B.; Shields, J. Factors related to social service workers’ job satisfaction: Revisiting Herzberg’s motivation to work. Adm. Soc. Work 2013, 37, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyak, H.A.; Namazi, K.H.; Kahana, E.F. Job commitment and turnover among women working in facilities sewing older persons. Res. Aging 1997, 19, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, A. Commitment and job satisfaction as predictors of turnover intentions among welfare workers. Adm. Soc. Work 2005, 29, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C. A public management for all seasons? Public Adm. 1991, 69, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, M.S.; Cheung, F.C.H. Gone with the wind: The impacts of managerialism on human services. Br. J. Soc. Work 2004, 34, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, G.A. Public and private management: What’s the difference? J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, J. Welfare, law and managerialism inter-discursivity and inter-professional practice in child care social work. J. Soc. Work 2008, 8, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropman, J.E. Managerialism in social work—An exploration of issues on the United States. Hong Kong J. Soc. Work. 2002, 36, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordegraaf, M. From "Pure" to "Hybrid" professionalism—Present-day professionalism in ambiguous public domains. Adm. Soc. 2007, 39, 761–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Thomas, R. Managerialism and accountability in higher education: The gendered nature of restructuring and the costs to academic service. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2002, 13, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, C. ‘We are all managers now’;‘we always were’: On the development and demise of management. J. Manag. Stud. 1999, 36, 561–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.; Payne, M. Managerialism and state social work in Britain. Hong Kong J. Soc. Work. 2002, 36, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olakivi, A.; Niska, M. Rethinking managerialism in professional work: From competing logics to overlapping discourses. J. Prof. Organ. 2017, 4, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeenk, S.; Teelken, C.; Eisinga, R.; Doorewaard, H. Managerialism, organizational commitment, and quality of job performances among European university employees. Res. High. Educ. 2009, 50, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chan, K. The difficulties and dilemma of constructing a model for teacher evaluation in higher education. High. Educ. Manag. 2001, 13, 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Popple, P.R. The social work profession: A reconceptualization. Soc. Serv. Rev. 1985, 59, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, A.; Schmader, T.; Block, K. An underexamined inequality: Cultural and psychological barriers to men’s engagement with communal roles. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 19, 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M. Fostering teacher professionalism in schools the role of leadership orientation and trust. Educ. Admin. Q. 2009, 45, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, C. The consequences for women in the academic profession of the widespread use of fixed term contracts. Gend. Work Organ. 2004, 11, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Hsiao, Y.Y.; Song, J.H.; Kim, J.; Bae, S.H. The moderating role of transformational leadership on work engagement: The influences of professionalism and openness to change. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2016, 27, 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, A.R. Accounting professionalism-They just don’t get it! Account. Horiz. 2004, 18, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen-Tsang, A.W.K.; Wang, S.B. Tensions confronting the development of social work education in China—Challenges and opportunities. Int. Soc. Work 2002, 45, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q.; Yu, Q.; Yu, F.F.; Huang, Y.X.; Zhang, L.L. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Snizek-revised Hall’s Professionalism Inventory Scale. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 1154–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.P.; Staines, G.L. The 1977 Quality of Employment Survey: Descriptive Statistics, with Comparison Data from the 1969–70 and the 1972–73 Surveys; Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, C.; Schudrich, W.Z.; Lawrence, C.K.; Claiborne, N.; McGowan, B.G. Predicting Turnover: Validating the Intent to Leave Child Welfare Scale. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2014, 24, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C. The new public management in the 1980s—Variations on a theme. Account. Organ. Soc. 1995, 20, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinnett, K.; Alexander, J.A. The influence of organizational context on quitting intention: An examination of treatment staff in long-term mental health care settings. Res. Aging 1999, 21, 176–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, J.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Nuchols, B.A. The effect of the social organization of work on the voluntary turnover rate of hospital nurses in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 34, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Somers, M.J. Modelling employee withdrawal behaviour over time: A study of turnover using survival analysis. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1996, 69, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Ketchen, D.J.; Arrfelt, M. Strategic supply chain management: Improving performance through a culture of competitiveness and knowledge development. Strateg. Manage. J. 2007, 28, 1035–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2013, 38, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeboye, N.; Fagoyinbo, I.; Olatayo, T. Estimation of the effect of multicollinearity on the standard error for regression coefficients. J. Math. 2014, 10, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Social control theory and delinquency: A longitudinal test. Criminololgy 1985, 23, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research- Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, J.L.; MacKinnon, D.P. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2001, 36, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Asociates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Bader, S.H. Work satisfaction, burnout, and turnover among social workers in Israel: A causal diagram. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2000, 9, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudrich, W.; Auerbach, C.; Liu, J.Q.; Fernandes, G.; McGowan, B.; Claiborne, N. Factors impacting intention to leave in social workers and child care workers employed at voluntary agencies. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, F.; Meyer, M.; Steinbereithner, M. Nonprofit Organizations Becoming Business-Like: A Systematic Review. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2016, 45, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikenberry, A.M.; Kluver, J.D. The marketization of the nonprofit sector: Civil society at risk? Public Adm. Rev. 2004, 64, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, R. Survival of the nonprofit spirit in a for-profit world. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 1992, 21, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B. Charity for profit? Exploring factors associated with the commercialization of human service nonprofits. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2006, 35, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, P.; Mishra, D. Conceptualising market orientation in non-profit organisations: Definition, performance, and preliminary construction of a scale. J. Mark. Manag. 2010, 26, 548–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersberger-Langloh, S.E.; Stuhlinger, S.; von Schnurbein, G. Institutional isomorphism and nonprofit managerialism: For better or worse? Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2021, 31, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courpasson, D. Managerial strategies of domination. Power in soft bureaucracies. Organ. Stud. 2000, 21, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewirtz, S.; Ball, S.; Bowe, R. Markets, Choice and Equity in Education; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Deem, R.; Brehony, K.J. Management as ideology: The case of ‘new managerialism’in higher education. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2005, 31, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorewaard, H.; van Bijsterveld, M. The osmosis of ideas: An analysis of the integrated approach to IT management from a translation theory perspective. Organization 2001, 8, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, C.; Willmott, H. Just how managed is the McUniversity? Organ. Stud. 1997, 18, 287–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Lægreid, P. New public management: Design, resistance, or transformation? A study of how modern reforms are received in a civil service system. Public Product. Manag. Rev. 1999, 23, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.B. Discussing the indigenization of social work in China. Zhejiang Acad. J. 2001, 2, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousijn, W.; Giorgino, V.M.B. The complexities of negotiating governance change: Introducing managerialism in Italy. Health Econ. Policy Law 2009, 4, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.B. The embedded develoment of social work in China. Soc. Sci. Front 2011, 2, 206–222. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, T.; Hinings, C.R. Managing the Rivalry of Competing Institutional Logics. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 128 | 19.2 |

| Female | 539 | 80.8 | |

| Age | <30 | 419 | 62.8 |

| 30–40 | 217 | 32.5 | |

| 40+ | 31 | 4.6 | |

| Education | HS/TS diploma | 31 | 4.6 |

| JC/VC degree | 262 | 39.3 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 374 | 56.1 | |

| Years of work experience | <2 years | 229 | 34.3 |

| 2–5 years | 282 | 42.3 | |

| 6–10 years | 115 | 17.2 | |

| >10 years | 41 | 6.1 | |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1.42 | 0.58 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Education | 2.51 | 0.59 | −0.03 | 1 | |||||

| 3. Years of work experience | 1.95 | 0.87 | 0.44 ** | 0.10 * | 1 | ||||

| 4. Professionalism | 4.39 | 0.79 | 0.10 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.04 | 1 | |||

| 5. Managerialism | 2.22 | 0.67 | −0.11 ** | 0.09 * | −0.03 | −0.57 ** | 1 | ||

| 6. Job satisfaction | 3.82 | 0.64 | 0.14 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.08 * | 0.61 ** | −0.55 ** | 1 | |

| 7. Turnover intention | 2.87 | 0.90 | −0.18 ** | 0.08 * | −0.08 * | −0.37 ** | 0.39 ** | −0.53 ** | 1 |

| Outcome Variable: Job Satisfaction | Outcome Variable: Turnover Intention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Age | 0.117 ** | 0.047 | 0.050 | −0.174 *** | −0.128 ** | −0.131 ** |

| Education | −0.116 ** | −0.005 | −0.008 | 0.073 | 0.010 | 0.013 |

| Years of experience | −0.040 | 0.034 | 0.032 | −0.014 | −0.011 | −0.009 |

| Professionalism | 0.441 *** | 0.478 *** | −0.217 *** | −0.257 *** | ||

| Managerialism | −0.289 *** | −0.265 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.221 *** | ||

| Professionalism × Managerialism | 0.112 *** | −0.121 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.033 | 0.438 | 0.450 | 0.038 | 0.201 | 0.214 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.028 | 0.434 | 0.445 | 0.034 | 0.195 | 0.207 |

| ΔR2 | 0.033 | 0.405 | 0.012 | 0.038 | 0.162 | 0.014 |

| F | 7.473 *** | 238.300 *** | 13.949 *** | 8.832 *** | 67.172 *** | 11.374 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Wong, H.; Liu, J. Why do Social Workers Leave? A Moderated Mediation of Professionalism, Job Satisfaction, and Managerialism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010230

Liu Z, Wong H, Liu J. Why do Social Workers Leave? A Moderated Mediation of Professionalism, Job Satisfaction, and Managerialism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010230

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ziyu, Hung Wong, and Jifang Liu. 2023. "Why do Social Workers Leave? A Moderated Mediation of Professionalism, Job Satisfaction, and Managerialism" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010230

APA StyleLiu, Z., Wong, H., & Liu, J. (2023). Why do Social Workers Leave? A Moderated Mediation of Professionalism, Job Satisfaction, and Managerialism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010230