The Longitudinal Effects of Depression on Academic Performance in Chinese Adolescents via Peer Relationships: The Moderating Effect of Gender and Physical Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Depression and Academic Performance

1.2. Depression, Academic Performance, and Peer Relationship

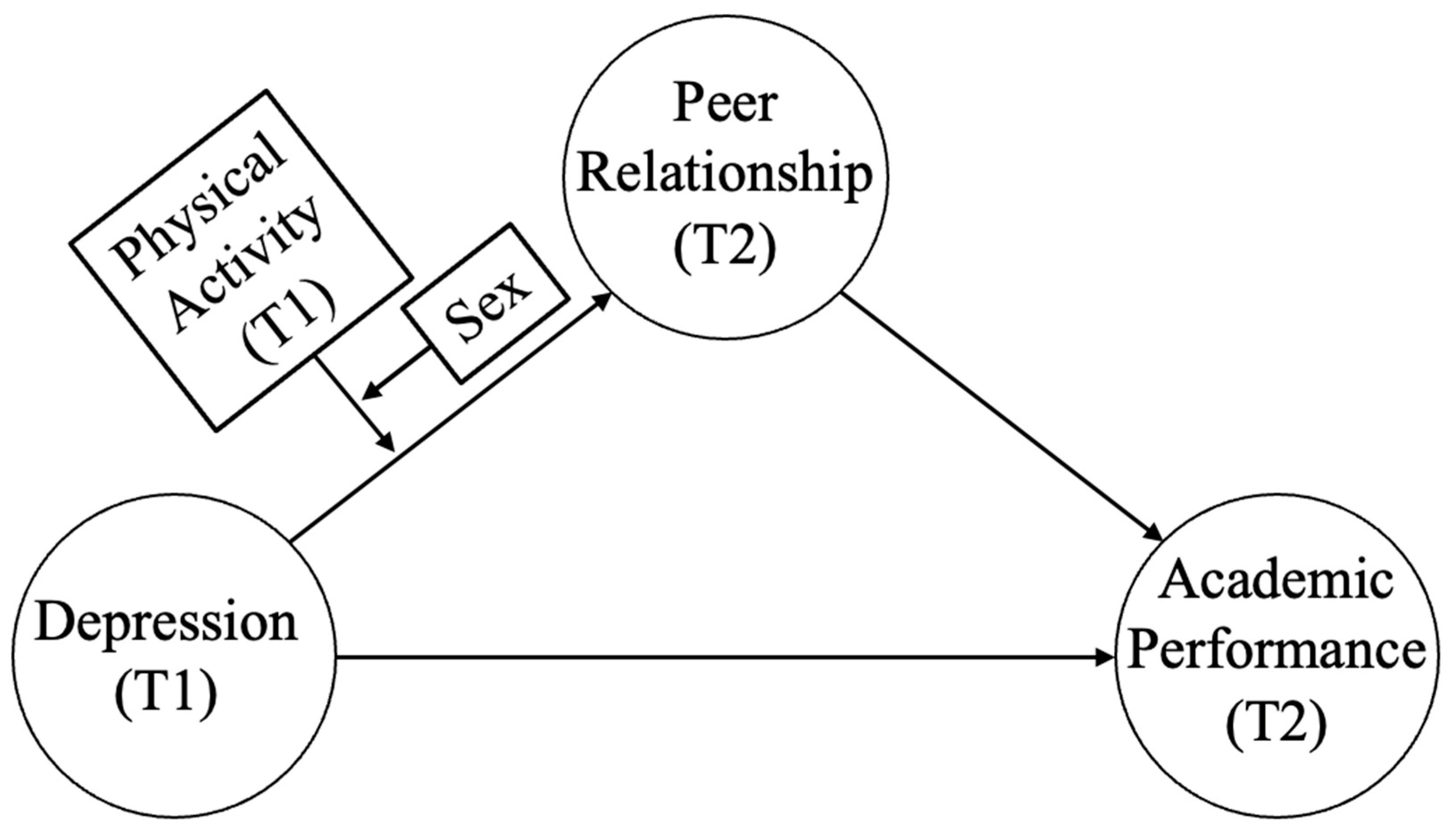

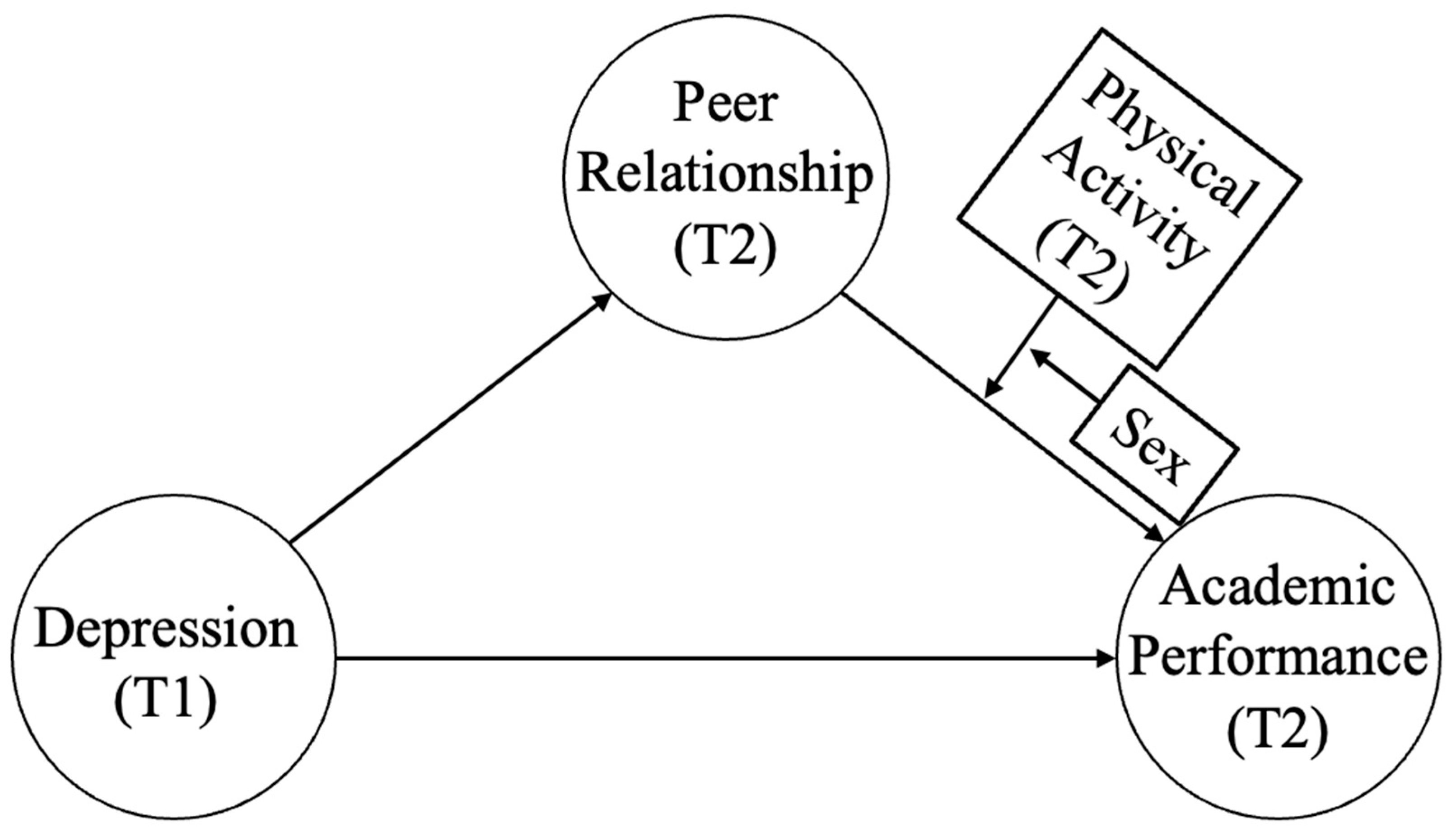

1.3. The Role of Moderator Variable: Gender and Physical Activity

1.4. Summary and Research Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Subjects

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Physical Activity (PA)

2.2.2. Academic Performance (AP)

2.2.3. Perceived Depression (PD)

2.2.4. Perceived Peer Relationship (PPR)

2.2.5. Covariates

2.2.6. Analysis Method

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Basic Statistics

3.2. Testing the Moderated Mediation Effect

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, D.; Quan, Z.; Ai, M.; Zong, C.; Xu, J. Adolescent mental health status and influencing factors. China J. Health Psychol. 2020, 9, 1402–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G.W. Children’s Peer Relations and Social Competence: A Century of Progress; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Suldo, S.M.; Shaffer, E.J. Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. Sch. Psychcol. Rev. 2008, 37, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.E.; Dishion, T.J. From boys to men: Predicting adult adaptation from middle childhood sociometric status. Dev. Psychopathol. 2004, 16, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Prinstein, M.J.; Aikins, J.W. Cognitive moderators of the longitudinal association between peer rejection and adolescent depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2004, 32, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinstein, M.J.; Cillessen, A.H. Forms and functions of adolescent peer aggression associated with high levels of peer status. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2003, 49, 310–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhs, E.S.; Ladd, G.W. Peer rejection as antecedent of young children’s school adjustment: An examination of mediating processes. Dev. Psychol. 2001, 37, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boivin, M.; Hymel, S.; Bukowski, W.M. The roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and victimization by peers in predicting loneliness and depressed mood in childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 1995, 7, 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Geiger, T.C.; Crick, N.R. Relational and physical aggression, prosocial behavior, and peer relations: Gender moderation and bidirectional associations. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 421–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K.R.; Caldwell, K. Friendships, peer acceptance, and group membership: Relations to academic achievement in middle school. Child Dev. 1997, 68, 1198–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingery, J.N.; Erdley, C.A.; Marshall, K.C. Peer acceptance and friendship as predictors of early adolescents’ adjustment across the middle school transition. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2011, 57, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, S.; Hejazi, E.; Lavasani, M.G. The relationships between personality traits and students’ academic achievement. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 29, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenyu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Ying, L.; Simin, Z.; Xuechen, D.; Gangmin, X. Developmental trajectories of depression and academic achievement in children: Based on parallel latent growth modeling. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2021, 19, 223. Available online: https://www.doc88.com/p-80859587535353.html (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Cattelino, E.; Chirumbolo, A.; Baiocco, R.; Calandri, E.; Morelli, M. School achievement and depressive symptoms in adolescence: The role of self-efficacy and peer relationships at school. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 52, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verboom, C.E.; Sijtsema, J.J.; Verhulst, F.C.; Penninx, B.W.; Ormel, J. Longitudinal associations between depressive problems, academic performance, and social functioning in adolescent boys and girls. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, F.; Mansor, M.B.; Juhari, R.B.; Redzuan, M.; Talib, M.A. The relationship between gender, age, depression and academic achievement. Curr. Res. Psychol. 2010, 6, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Pastorelli, C.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V. Self-efficacy pathways to childhood depression. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeck, N.; Carreno, D.F.; Uclés-Juárez, R. From psychological distress to academic procrastination: Exploring the role of psychological inflexibility. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2019, 13, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.; Arteche, A.; Fearon, P.; Halligan, S.; Croudace, T.; Cooper, P. The effects of maternal postnatal depression and child sex on academic performance at age 16 years: A developmental approach. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Academic achievement and subsequent depression: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, W.M.; Hoza, B. Popularity and friendship: Issues in theory, measurement, and outcome. In Peer Relationships in Child Development; Berndt, T., Ladd, G., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Youniss, J.; Haynie, D.L. Friendship in adolescence. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 1992, 13, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, J.C. Depression and the response of others. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1976, 85, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joiner, T.E.J. Depression in its interpersonal context. In Handbook of Depression; Gotlib, I.H., Hammen, C.L., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, K.D.; Flynn, M.; Abaied, J.L. A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression. In Child and Adolescent Depression: Causes, Treatment, and Prevention; Abela, J.R.Z., Hankin, B.L., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- DeRosier, M.E.; Lloyd, S.W. The impact of children’s social adjustment on academic outcomes. Read. Writ. Q. 2010, 27, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, L.O.; Barrasa, A.; Guevara-Viejo, F. Positive peer relationships and academic achievement across early and midadolescence. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2016, 44, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K.R. Relations of social goal pursuit to social acceptance, classroom behavior, and perceived social support. J. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 86, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howie, E.K.; Pate, R.R. Physical activity and academic achievement in children: A historical perspective. J. Sport Health Sci. 2012, 1, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Bueno, C.; Pesce, C.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Sánchez-López, M.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V. Academic achievement and physical activity: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20171498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.; Whiting, S.; Simmonds, P.; Scotini Moreno, R.; Mendes, R.; Breda, J. Physical activity and academic achievement: An umbrella review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandola, A.; Ashdown-Franks, G.; Hendrikse, J.; Sabiston, C.M.; Stubbs, B. Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 107, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Li, J.; Xu, F.; Tse, L.A.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, I.T.S.; Griffiths, S. Physical activity inversely associated with the presence of depression among urban adolescents in regional China. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, E.M.; Corcoran, P.; O’Regan, G.; Keeley, H.; Cannon, M.; Carli, V.; Wasserman, C.; Hadlaczky, G.; Sarchiapone, M.; Apter, A.; et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, E.; Leaper, C. A longitudinal investigation of sport participation, peer acceptance, and self-esteem among adolescent girls and boys. Sex Roles 2006, 55, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Shin, M.; Smith, A.L. The relationship of physical activity from physical education with perceived peer acceptance across childhood and adolescence. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, A.J.; Rudolph, K.D. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.; Leung, J.T.; Kwok, S.Y.; Hui, A.; Lo, H.; Tam, H.L.; Lai, S. Predictors to happiness in primary students: Positive relationships or academic achievement. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 2335–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.S.; Ambrosini, P.J.; Kudes, D.; Metz, C.; Rabinovich, H. Gender differences in adolescent depression: Do symptoms differ for boys and girls? J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 89, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, A.C.; Sarigiani, P.A.; Kennedy, R.E. Adolescent depression: Why more girls? J. Youth Adolesc. 1991, 20, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, T. Assessing the sociology of sport: On media and representations of sportswomen. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 2015, 50, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S.N. ‘Boys, when they do dance, they have to do football as well, for balance’: Young men’s construction of a sporting masculinity. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 2022, 57, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jago, R.; Anderson, C.B.; Baranowski, T.; Watson, K. Adolescent patterns of physical activity: Differences by gender, day, and time of day. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, J.; Weinberg, R.S.; Breckon, J.D.; Claytor, R.P. Adolescent physical activity participation and motivational determinants across gender, age, and race. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling. 2012. Available online: https://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (Multivariate Applications Series); Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Zhou, J.; Feng, L. Pro-social behavior is predictive of academic success via peer acceptance: A study of Chinese primary school children. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 65, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzner, J.; Becker, M.; Maaz, K. Development in multiple areas of life in adolescence: Interrelations between academic achievement, perceived peer acceptance, and self-esteem. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2017, 41, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, J. The root causes of gender problems in school sports in my country and their solutions. J. Phys. Educ. 2017, 24, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Lee, C.; Lee, Y. Effect of Aggression on Peer Acceptance Among Adolescents During School Transition and Non-Transition: Focusing on the Moderating Effects of Gender and Physical Education Activities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron-Gélinas, A.; Brendgen, M.; Vitaro, F. Can sports mitigate the effects of depression and aggression on peer rejection? J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 50, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaper, C.; Friedman, C.K. The socialization of gender. In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research; Grusec, J.E., Hastings, P.D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 561–587. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, J.R.; Díaz-Morales, J.F. Procrastination and mental health coping: A brief report related to students. Individ. Differ. Res. 2014, 12, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Martell, C.R.; Dimidjian, S.; Herman-Dunn, R. Behavioral Activation for Depression: A Clinician’s Guide; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.L.; Rose, A.J.; Schwartz-Mette, R.A. Relational and overt aggression in childhood and adolescence: Clarifying mean-level gender differences and associations with peer acceptance. Soc. Dev. 2010, 19, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SEX | - | |||||||||||

| 2. SES | −0.01 | - | ||||||||||

| 3. FEL | 0.03 * | 0.22 *** | - | |||||||||

| 4. MEL | 0.02 | 0.20 *** | 0.62 *** | - | ||||||||

| 5. PD(T1) | 0.02 | −0.13 *** | −0.04 ** | −0.04 *** | - | |||||||

| 6. PPR(T1) | 0.08 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.11 *** | −0.26 *** | - | ||||||

| 7. AP(T1) | 0.25 *** | −0.01 | 0.06 *** | 0.05 *** | −0.09 *** | 0.18 *** | - | |||||

| 8. PA(T1) | −0.10 ** | 0.06 ** | 0.05 ** | 0.04 ** | −0.06 ** | 0.16 ** | −0.03 ** | - | ||||

| 9. PD(T2) | 0.05 *** | −0.08 *** | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.41 *** | −0.17 ** | −0.04** | −0.02 * | - | |||

| 10. PPR(T2) | 0.06 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.09 *** | 0.09 *** | −0.22 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.10 *** | −0.26 *** | - | ||

| 11. AP(T2) | 0.20 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.21 *** | −0.15 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.61 *** | −0.003 | −0.08 *** | 0.20 *** | - | |

| 12. PA(T2) | −0.10 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.12 *** | −0.06 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.02 | 0.15 *** | −0.05 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.15 *** | - |

| Mean | 1.50 | 3.03 | 1.18 | 1.15 | 2.00 | 3.04 | 213.46 | 5.91 | 2.14 | 3.04 | 194.17 | 9.23 |

| SD | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.8 | 0.72 | 23.55 | 6.31 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 57.8 | 6.35 |

| Skewness | 0.03 | −0.11 | 1.75 | 2.04 | 1.07 | −0.53 | −0.92 | 1.59 | 0.91 | −0.5 | −0.75 | 1.53 |

| Kurtosis | −2.00 | 2.87 | 1.07 | 2.15 | 1.61 | −0.16 | 1.02 | 3.17 | 0.73 | −0.13 | −0.04 | 3.87 |

| PPR(T2) | AP(T2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | ||

| COV | SES | 0.04 *** | 0.09 *** |

| FEL | 0.03 * | 0.10 *** | |

| MEL | 0.01 | 0.10 *** | |

| PPR(T1) | 0.36 *** | 0.08 *** | |

| PD(T2) | −0.17 ** | 0.001 | |

| AP(T1) | 0.04 *** | 0.57 *** | |

| PA(T1) | 0.06 *** | −0.01 | |

| MOV | Sex c | 0.12 *** | |

| PA(T2) b | 0.02 *** | ||

| IV | PD(T1) | −0.04 ** | −0.05 *** |

| PPR(T2) a | 0.04 *** | ||

| a × b | −0.03 ** | ||

| a × c | −0.02 | ||

| b × c | 0.06 ** | ||

| IT | a × b × c | −0.04 * | |

| R | 0.48 | 0.68 | |

| R2 | 0.23 | 0.46 | |

| F (8, 7161) = 261.61 *** | F (15, 7154) = 414.25 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bi, Y.; Moon, M.; Shin, M. The Longitudinal Effects of Depression on Academic Performance in Chinese Adolescents via Peer Relationships: The Moderating Effect of Gender and Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010181

Bi Y, Moon M, Shin M. The Longitudinal Effects of Depression on Academic Performance in Chinese Adolescents via Peer Relationships: The Moderating Effect of Gender and Physical Activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010181

Chicago/Turabian StyleBi, Yingchen, Minkwon Moon, and Myoungjin Shin. 2023. "The Longitudinal Effects of Depression on Academic Performance in Chinese Adolescents via Peer Relationships: The Moderating Effect of Gender and Physical Activity" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010181

APA StyleBi, Y., Moon, M., & Shin, M. (2023). The Longitudinal Effects of Depression on Academic Performance in Chinese Adolescents via Peer Relationships: The Moderating Effect of Gender and Physical Activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010181