Navigating Voice, Vocabulary and Silence: Developing Critical Consciousness in a Photovoice Project with (Un)Paid Care Workers in Long-Term Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Main Objectives

2. Theoretical Framework

Intersectionality

3. Setting

Societal Context of Our Photovoice Project “Negotiating Health”

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Approach

4.2. Phases of Our Research Process

4.3. First, Second and Third-Person Reflection

5. Results: Reflections on Voice, Vocabulary and Silence in Photovoice

- In the first theme, “What on earth am I doing?”, we described how we developed critical consciousness on gendered inequities. This process took place in phase 1 of our photovoice project.

- In the second theme “We should all be wearing yellow vests”, we describe how critical consciousness led to us speaking out about inequities that were shaped at the intersection of gender and class. This process took place at the beginning of phase 2 of our photovoice project.

- In the third theme, “You’d rather not see it”, we not only describe how we broke the silence on racial inequities but also how we were consequently silenced by each other and by change agents. This process took place at the end of phase 2 of our photovoice project.

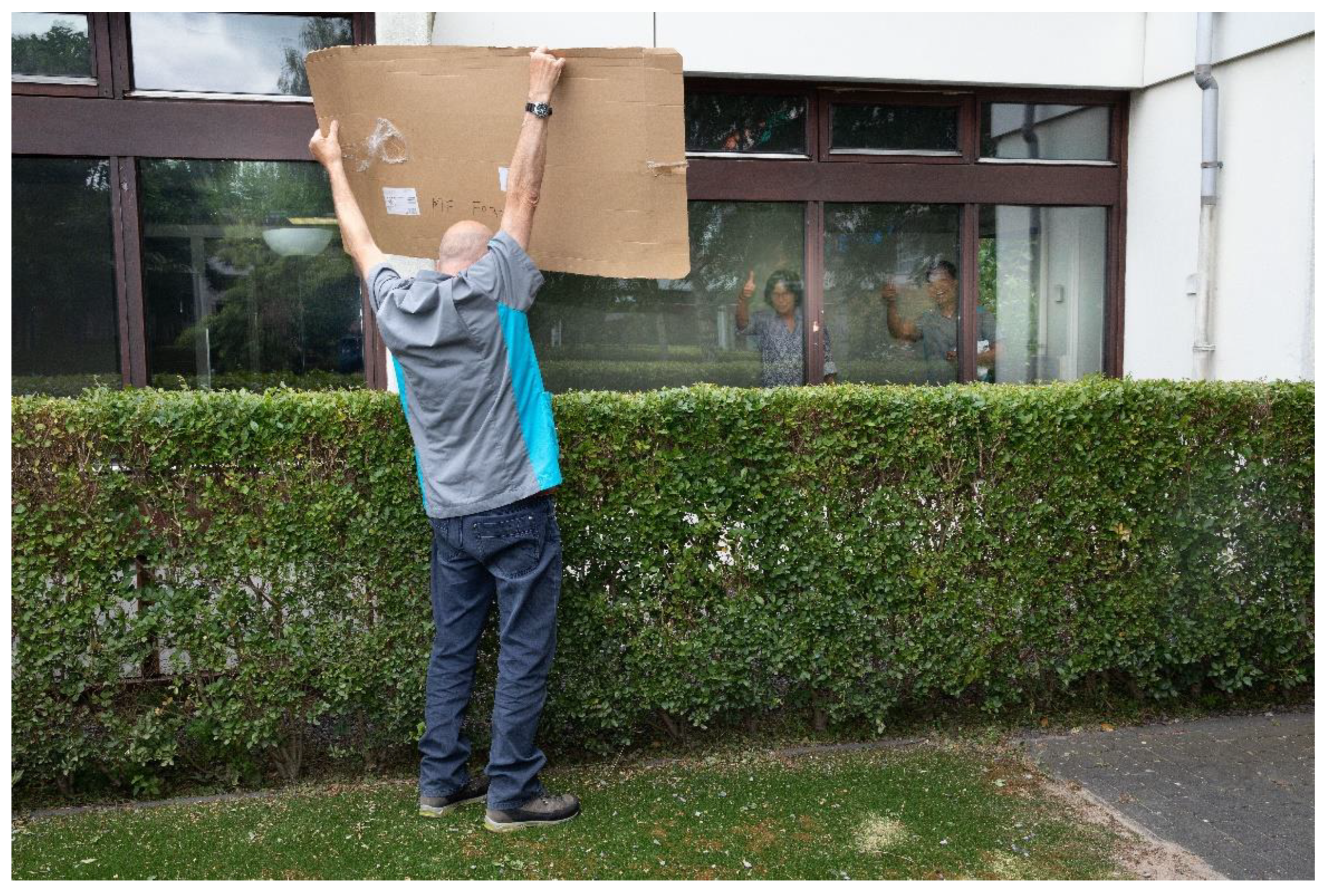

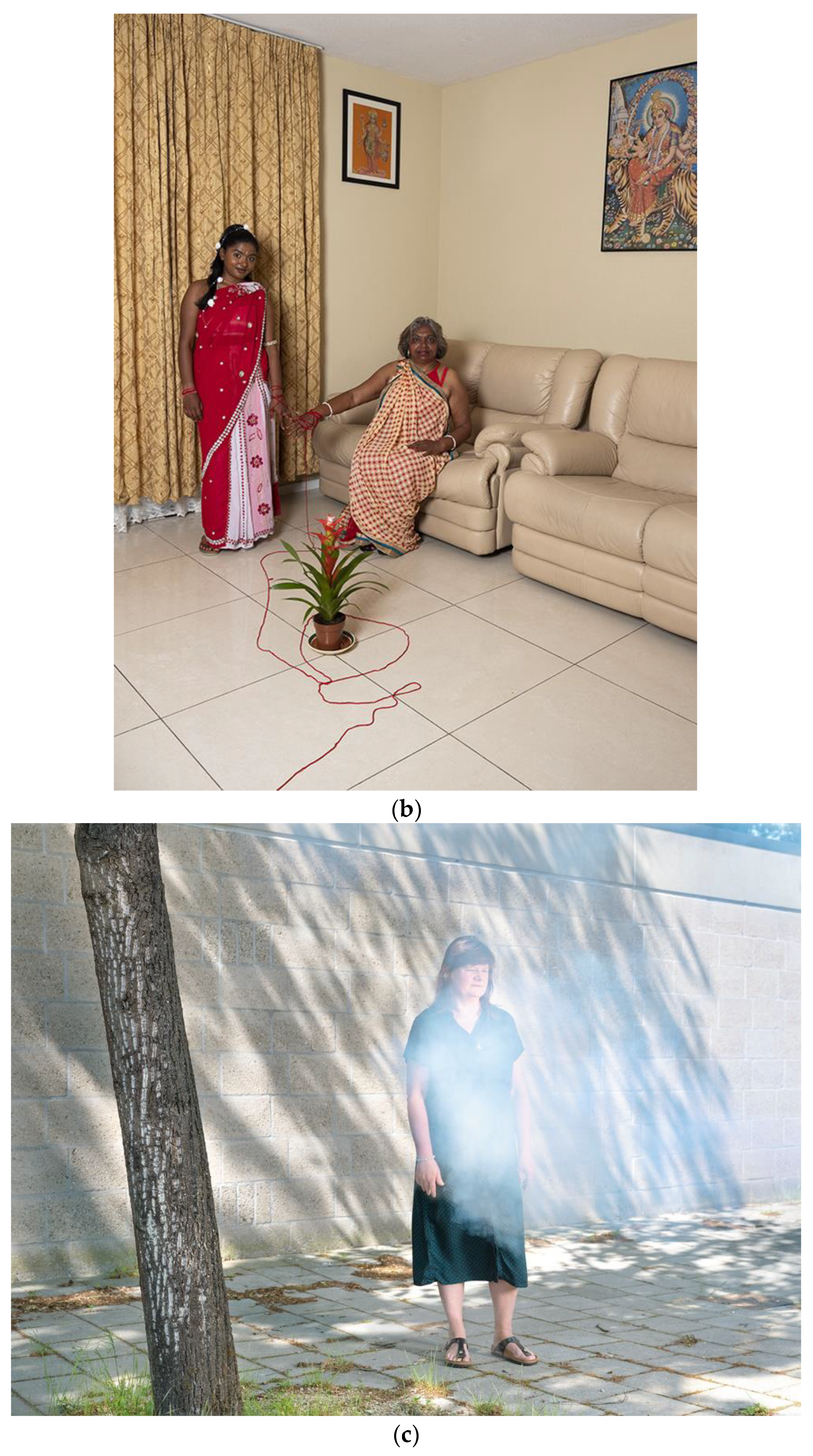

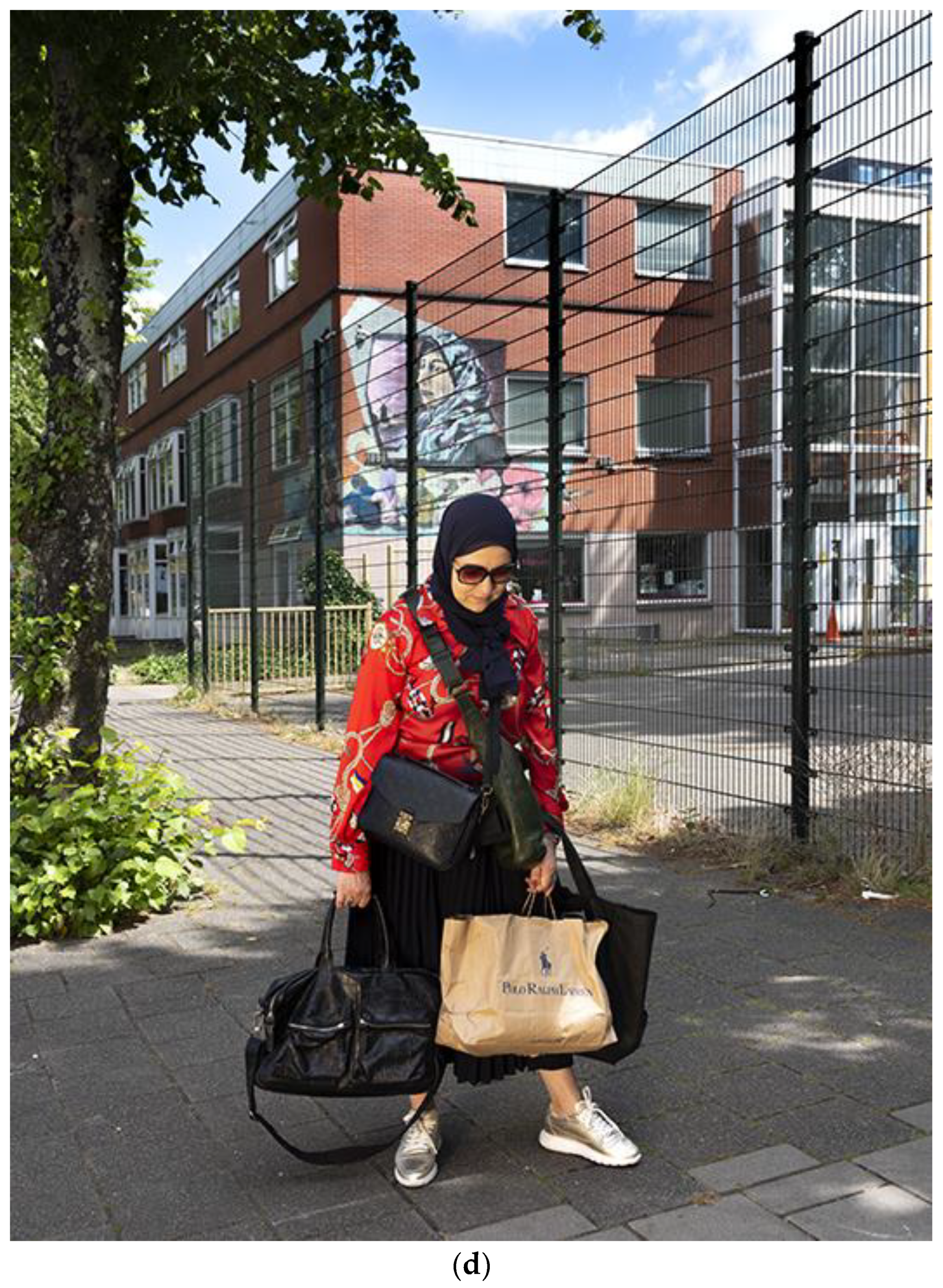

- In the fourth theme, “What you don’t see”, we present the portraits and booklet that we created and used in dialogue with change agents. These portraits and booklet describe how the health and wellbeing of paid care workers in long-term care is shaped at the intersection of gender, class and race. This process takes place in phase 4 of our photovoice project.

5.1. ‘What on Earth Am I Doing?’ Developing Critical Consciousness on Gendered Inequities

‘If you make a photo, you literally have to stand still and look at your live. And then it also becomes visible for others. When I looked at my own pictures, I realized: what on earth am I doing? That made me think about my life’.(community researcher)

‘You start talking and recognize things from each other. That’s when you start thinking: “this is not normal”.(community researcher)

‘Directing the camera towards your own life starts a reflective process. It urges you to think about what you see in the picture. To attribute meaning to it. You often start by what is unconsciously captured in the picture, by what is ‘inside’ you. It’s like soil. You start digging, shuffle and wield the ground, and allow for the air to come in’.(photographer)

‘For me, these moments were really eye-opening. You just realize, wow, what happened to me (pregnancy discrimination) was not just an incident. I started to look back at certain life events, and started to see them in a new light.’(community researcher)

‘If you don’t have the words to describe what happened to you, then how can you speak about it? If it’s something that is never spoken about, you don’t hear the experiences of others, and you are the first to put it into words, that is just so hard. It’s not likely that it will surface, or that you will speak out.’(academic researcher)

‘It’s a process of trial and error, and that’s no problem as long as you stay connected with each other throughout this tension. If participants don’t respond to our input, we can reflect on it, maybe they need time to process, maybe they cannot relate. Either way, it requires courage to stay close to ‘what is’, that is the hardest thing to do.’(photographer)

5.2. “We Should Be Wearing Yellow Vests!” Speaking out about Inequity at the Intersection of Gender and Class

“And suddenly I was very ashamed, that in these peaceful times, I am afraid to put my name under a newspaper op-ed. Notably, the resistance newspaper that my father risked his life for many years ago.”(Community researcher)

“This project enables to voice my concerns, speak out about the things that need to be heard. Our group makes me feel safe, and this safety helps you to articulate your experiences and voice them to others. I cannot always deal with the confrontation with managers or policy makers. They make you feel so small, so powerless. You don’t expect any support. They will downplay your story: “It’s not representative for the entire sector. It’s not happening. It’s not true.” And then you start believing, maybe you are right.”(Community researcher)

5.3. “You’d Rather Not See It” Breaking the Silence on Racism

“We have learned to stay silent. Be modest. Listen to your boss. My children are not like that. They would say to me: mom, speak out! The younger generation doesn’t stay silent, like we have learned to be.”(Community-researcher)

“Too often you are asked to participate in a research project that turns out to be about someone else’s agenda. They say it’s about us, but in the end, it is not about us at all. (…) Our stories are often just erased.”(Community researcher)

“I decided to quit with our project. I realized that I was very angry about something (…) Now, I realize that I feel attacked as a “white man”. It is very unpleasant to be held accountable as a member of a group, when this group is seen as something that is very different from who I am and how I see myself.”(Community researcher)

“Now I know the story behind the photograph, it is not as pretty to look at anymore. You’d rather not see it”.

“Our stories have a rough edge. You can consider it a bad thing, but it is what it is. It’s not like social media, where everything is covered up under a nice filter. This is reality. Our reality. A lot of people live in a different reality. Then our stories might be too rough and confronting. Not everybody is willing to look at it.”(Community researcher)

5.4. “What You Don’t See” a Book Voicing Critical Perspectives on Gender, Class and Race

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of Empirical Findings

6.2. Vocabularies Are Essential for Epistemic Justice

6.3. Engaging with “Interpretative Tropes” Requires Relational Sensitivity

6.4. Intersectionality Provides Essential “Interpretative Tropes” for Hermeneutic Justice

6.5. Learning to Listen to Silence

6.6. Speaking about Oppression Is Painful and Not “Positive” but Is Essential for Hermeneutic Justice

6.7. Strengths and Limitations of Our Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Catalani, C.; Minkler, M. Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Educ. Behav. 2010, 37, 424–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liebenberg, L. Thinking critically about photovoice: Achieving empowerment and social change. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17, 1609406918757631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, M.T.; Springett, J.; Kongats, K. What is participatory health research? In Participatory Health Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. (Eds.) Handbook of Action Research; Participative Inquiry and Practice, 2nd ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B.; Oetzel, J.G.; Minkler, M. (Eds.) Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M. Transformative Research and Evaluation; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of The Oppressed; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, T. Reframing photovoice: Building on the method to develop more equitable and responsive research practices. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubrium, A.; Harper, K. Participatory Visual and Digital Methods; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sanon, M.A.; Evans-Agnew, R.A.; Boutain, D.M. An exploration of social justice intent in photovoice research studies from 2008 to 2013. Nurs. Inq. 2014, 21, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coemans, S.; Raymakers, A.L.; Vandenabeele, J.; Hannes, K. Evaluating the extent to which social researchers apply feminist and empowerment frameworks in photovoice studies with female participants: A literature review. Qual. Soc. Work. 2019, 18, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, V.; Simons, J. A review of photovoice applications in environment, sustainability, and conservation contexts: Is the method maintaining its emancipatory intents? Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijs, S.E.; Baur, V.E.; Abma, T.A. Why action needs compassion: Creating space for experiences of powerlessness and suffering in participatory action research. Action Res. 2021, 19, 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassah, E.; Aldersey, H.M.; Norman, K.E. Photovoice and persons with physical disabilities: A scoping review of the literature. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 1412–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysyuk, Y.; Huisman, M. Photovoice method with older persons: A review. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 1759–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.S.; Oliffe, J.L. Photovoice in mental illness research: A review and recommendations. Health 2016, 20, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fountain, S.; Hale, R.; Spencer, N.; Morgan, J.; James, L.; Stewart, M.K. A 10-year Systematic Review of Photovoice Projects With Youth in the United States. Health Promot. Pract. 2021, 22, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suprapto, N.; Sunarti, T. A Systematic Review of Photovoice as Participatory Action Research Strategies. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2020, 9, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilagan, C.; Akbari, Z.; Sethi, B.; Williams, A. Use of Photovoice Methods in Research on Informal Caring: A Scoping Review of the Literature. J. Hum. Health Res. 2020, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsrud, K.; Eylem, O.; Mooney, R.; Haarmans, M.; Bhui, K. Identifying evidence of the effectiveness of photovoice: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the international healthcare literature. J. Public Health 2021, fdab074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofton, S.; Grant, A.K. Outcomes and Intentionality of Action Planning in Photovoice: A Literature Review. Health Promot. Pract. 2021, 22, 318–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, E.D.; Engebretson, J.; Chamberlain, R.M. Photovoice as a social process of critical consciousness. Qual. Health Res. 2006, 16, 836–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, M.; Torre, M.E.; Oswald, A.G.; Avory, S. Critical participatory action research: Methods and praxis for intersectional knowledge production. J. Couns. Psychol. 2021, 68, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, M.; Torre, M.E. Critical participatory action research: A feminist project for validity and solidarity. Psychol. Women Q. 2019, 43, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, M.; Myroniuk, T.; Epping, S.; Lewis, K.; Liebenberg, L. A Photovoice Exploration of the Lived Experience of Intersectional Stigma among People Living with HIV. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 3223–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapilashrami, A.; Marsden, S. Examining intersectional inequalities in access to health (enabling) resources in disadvantaged communities in Scotland: Advancing the participatory paradigm. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlatte, O.; Oliffe, J.L. Picturing intersectionality in men’s suicidality research: A photovoice case study of gay and bisexual men. In Men’s Health Equity; Griffith, D.M., Bruce, M.A., Thorpe, R.J., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 524–540. [Google Scholar]

- Verdonk, P.; Muntinga, M.; Leyerzapf, H.; Abma, T.A. From gender sensitivity to an intersectionality and participatory approach in health research and public policy in the Netherlands. In The Palgrave Handbook of Intersectionality in Public Policy; Hankivsky, O., Jordan-Zachery, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 413–432. [Google Scholar]

- Combahee River Collective. The Combahee River Collective Statement; Combahee River Collective: Boston, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, A.M. When multiplication doesn’t equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a research paradigm. Perspect. Politics 2007, 5, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H.; Bilge, S. Intersectionality, 2nd ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1990, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankivsky, O. Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 74, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankivsky, O.; Doyal, L.; Einstein, G.; Kelly, U.; Shim, J.; Weber, L.; Repta, R. The odd couple: Using biomedical and intersectional approaches to address health inequities. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1326686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengelaar, A.H.; Wittenberg, Y.; Kwekkeboom, R.; Van Hartingsveldt, M.; Verdonk, P. Intersectionality in informal care research: A scoping review. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, L. The complexity of intersectionality. Signs 2005, 30, 1771–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Purdie-Vaughns, V.; Eibach, R.P. Intersectional invisibility: The distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate-group identities. Sex Roles 2008, 59, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijs, S.E.; Verdonk, P.; Abma, T.A. “Dat zorgende zit gewoon in me” Toenemende Genderongelijkheid in de Participatiemaatschappij. Tijdschr. Voor Soc. Vraagst. 2019, 3, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurel, C.; Abma, T.A. Medewerkers Betalen de Prijs van Betere Verpleeghuiszorg. Trouw. Available online: https://www.trouw.nl/opinie/medewerkers-betalen-de-prijs-van-betere-verpleeghuiszorg~b5d0a0f7/ (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Duijs, S.E.; Wees, M.; Abena-Jaspers, Y.; Jhingoeri, U.; Senoussi, N.; Plak, O.; Abma, T.A.; Verdonk, P. “We just take care of each other” relational caring strategies of low-paid women working in residential long-term care, insights from an intersectional qualitative study. 2022; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Wees, M.; Duijs, S.E.; Mazurel, C.; Abma, T.A.; Verdonk, P. Negotiating Masculinities at the Expense of Health: A qualitative study on low-paid men working in long-term care in the Netherlands from an intersectional perspective. Gend. Work. Organ. 2022; accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Duijs, S.E.; Abena-Jaspers, Y.; Jhingoeri, U.; Senoussi, N.; Plak, O.; Abma, T.A.; Verdonk, P. Squeezed out: Experiences of precariousness by self-employed care workers in long-term care, from an intersectional perspective. 2022; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Duijs, S.E.; Haremaker, A.; Bourik, Z.; Abma, T.A.; Verdonk, P. Pushed to the Margins and Stretched to Limits: Experiences of Freelance Eldercare Workers During the Covid-19 Pandemic in the Netherlands. Fem. Econ. 2021, 27, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, C.; Frisby, W. Continuing the journey: Articulating dimensions of feminist participatory action research (FPAR). In Sage Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice; Reason, P., Bradbury, H., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen, M.M.; Gergen, K.J. Playing with Purpose: Adventures in Performative Social Science, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, P.; Torbert, W. The action turn: Toward a transformational social science. Concepts Transform. 2001, 6, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malhotra, S.; Rowe, A.C. (Eds.) Silence, Feminism, Power: Reflections at The Edges of Sound; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Skeggs, B. Formations of Class & Gender: Becoming Respectable; Sage Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Forssén, A.S.; Carlstedt, G.; Mörtberg, C.M. Compulsive sensitivity—A consequence of caring: A qualitative investigation into women carer’s difficulties in limiting their labours. Health Care Women Int. 2005, 26, 652–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharya, T. Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N.; Jaeggi, R. Capitalism: A Conversation in Critical Theory; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, L.; Ferguson, S.; McNally, D. Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory; Rutgers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, C. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, J.C. Caring Democracy; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Westerlaken, A. De Zorg Moet van Patiënt Centraal naar Medewerker Centraal. Trouw. Available online: https://www.trouw.nl/opinie/de-zorg-moet-van-patient-centraal-naar-medewerker-centraal~bb08d169/ (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Haalboom-Schram, N. Hoe meer Winst, Hoe Beter We Werken in de Zorg. Of Niet? Trouw. Available online: https://www.trouw.nl/opinie/hoe-meer-winst-hoe-beter-we-werken-in-de-zorg-of-niet~b7af7e38/ (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Muntinga, M.; Verdonk, P. Waarom gaat het Vooral over Corona? Tegen Racisme Komt Geen Vaccin. Parool. Available online: https://www.parool.nl/columns-opinie/waarom-gaat-het-vooral-over-corona-tegen-racisme-komt-geen-vaccin~b7d69ada3/ (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Carel, H.; Kidd, I.J. Epistemic injustice in medicine and healthcare. In The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice; Kidd, I.J., Medina, J., Pohlhaus, G., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 336–346. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale, F.A. A “Thick” Conception of Children’s Voices: A Hermeneutical Framework for Childhood Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan-Flood, R.; Gill, R. Secrecy and Silence in the Research Process, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gatwiri, G.J.; Mumbi, K.A. Silence as power: Women bargaining with patriarchy in Kenya. Soc. Altern. 2016, 35, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Berg, T. “And we gossip about my life as if I am not there.” An autoethnography on recovery from infidelity and silence in the academic workplace. Hum. Relat. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros, K.; Rubinstein, R.L. Shadow stories in oral interviews: Narrative care through careful listening. J. Aging Stud. 2015, 34, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blix, B. The importance of untold and unheard stories in narrative gerontology: Reflections on a field still in the making from a narrative gerontologist in the making. Narrat. Work. 2016, 6, 28–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, C.W. The Racial Contract; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. The Promise of Happiness; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, J.; Van Den Berg, M. Pedagogies of optimism: Teaching to ‘look forward’ in activating welfare programmes in The Netherlands. Crit. Soc. Policy 2019, 39, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Year | Activities | Participants | Results | Typology of Hermeneutic Understanding | Critical Lens |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2018–2019 | Photovoice (n = 10 meetings) | 10 (un)paid caregivers | Article in journal for professionals in the health and social care domain [40] | Academic researchers reflecting about participants’ photographs and narratives | Gender |

| 2 | 2019–2021 | Photovoice | 5 co-researchers | Op-ed in national newspaper [41] | Dialogue between co-researchers, photographer and academic researchers | Gender/Class |

| 3 | 2019–2021 | PHR projects | 5 co-researchers | Scientific article #1 [42] Scientific article #2 [43] Scientific article #3 [44] Scientific article #4 [45] | Academic researchers and co-researchers reflecting about respondents in the qualitative sub-studies of Negotiating Health | Gender/Class/ Race/Disability/Sexuality |

| 4 | 2019–2021 | Photovoice | 5 co-researchers | Portraits and Book | Co-creation of portraits and book | Gender/Class/ Race/Disability/Sexuality |

| 5 | 2021–2022 | Dialogue and Action | 4 co-researchers | Dialogue meetings with change agents Book presentation | Dialogue with change agents | Gender/Class/Race/Disability Sexuality |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duijs, S.E.; Abma, T.; Schrijver, J.; Bourik, Z.; Abena-Jaspers, Y.; Jhingoeri, U.; Plak, O.; Senoussi, N.; Verdonk, P. Navigating Voice, Vocabulary and Silence: Developing Critical Consciousness in a Photovoice Project with (Un)Paid Care Workers in Long-Term Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095570

Duijs SE, Abma T, Schrijver J, Bourik Z, Abena-Jaspers Y, Jhingoeri U, Plak O, Senoussi N, Verdonk P. Navigating Voice, Vocabulary and Silence: Developing Critical Consciousness in a Photovoice Project with (Un)Paid Care Workers in Long-Term Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(9):5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095570

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuijs, Saskia Elise, Tineke Abma, Janine Schrijver, Zohra Bourik, Yvonne Abena-Jaspers, Usha Jhingoeri, Olivia Plak, Naziha Senoussi, and Petra Verdonk. 2022. "Navigating Voice, Vocabulary and Silence: Developing Critical Consciousness in a Photovoice Project with (Un)Paid Care Workers in Long-Term Care" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 9: 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095570

APA StyleDuijs, S. E., Abma, T., Schrijver, J., Bourik, Z., Abena-Jaspers, Y., Jhingoeri, U., Plak, O., Senoussi, N., & Verdonk, P. (2022). Navigating Voice, Vocabulary and Silence: Developing Critical Consciousness in a Photovoice Project with (Un)Paid Care Workers in Long-Term Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095570