Investigation on the Relationship between Biodiversity and Linguistic Diversity in China and Its Formation Mechanism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

3. Results

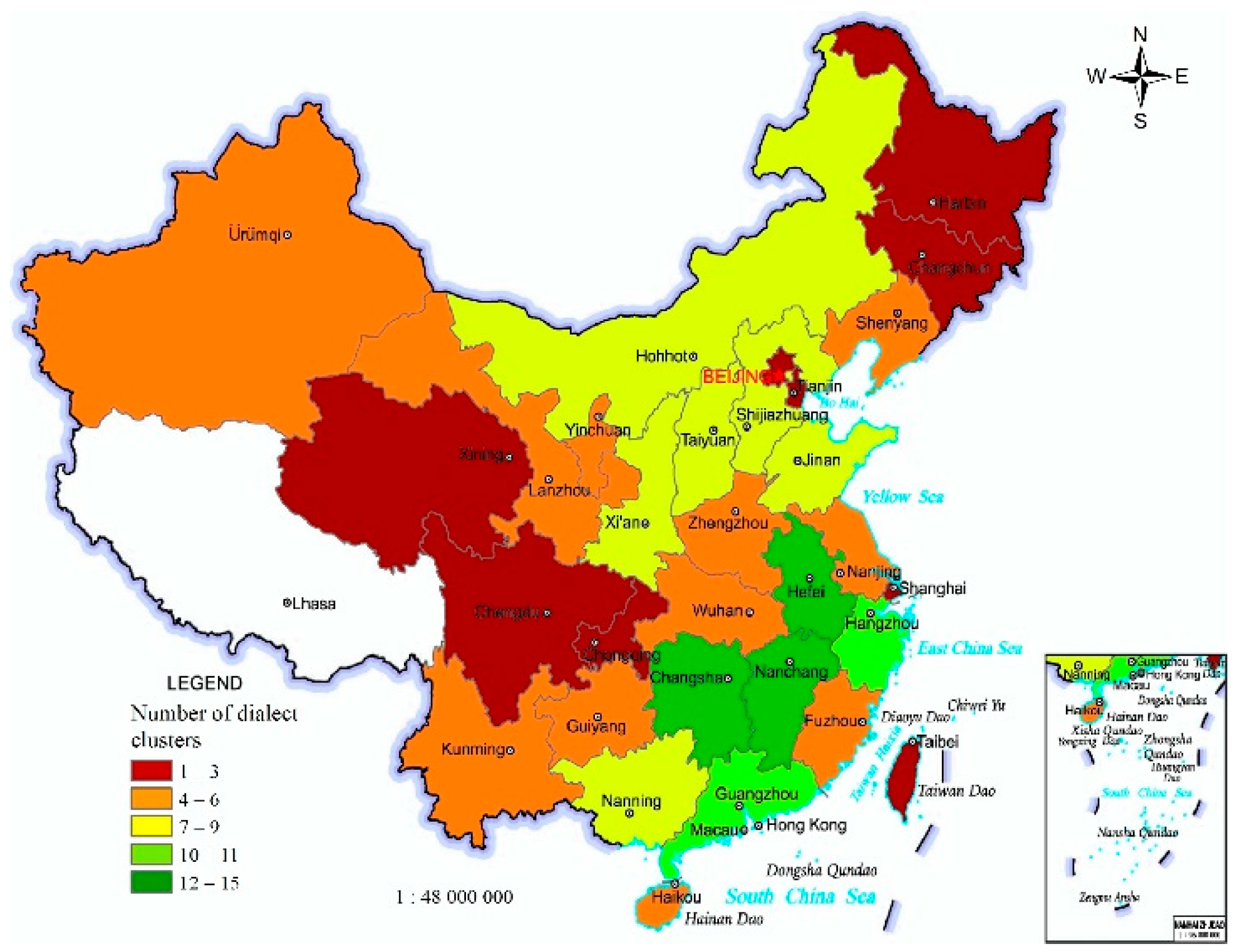

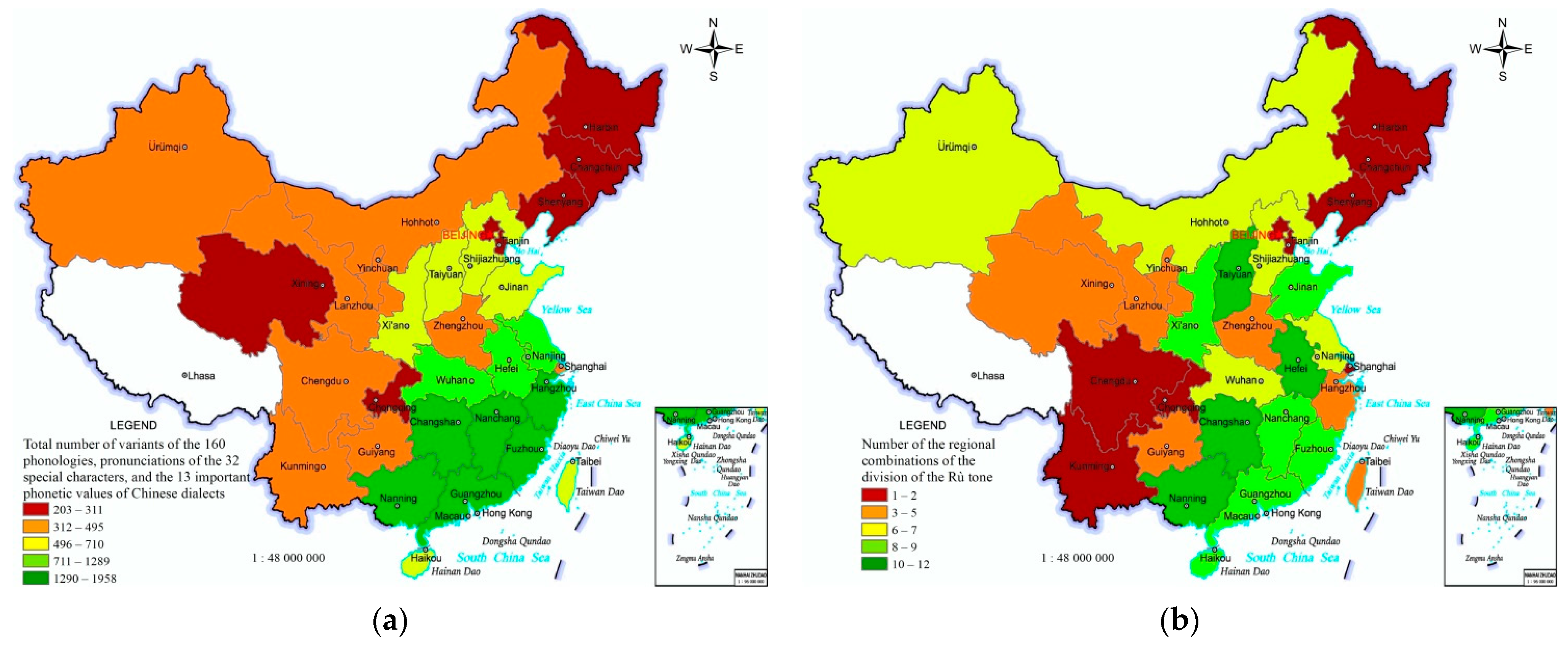

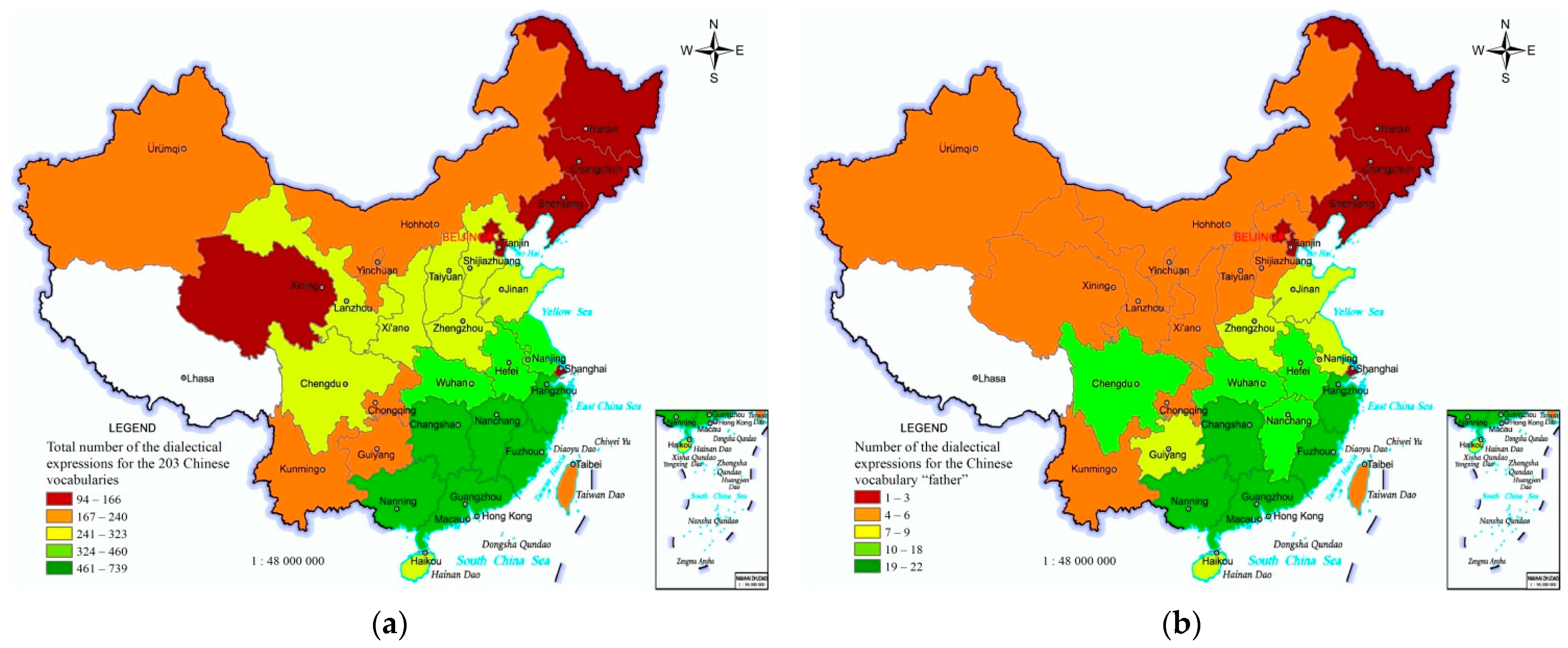

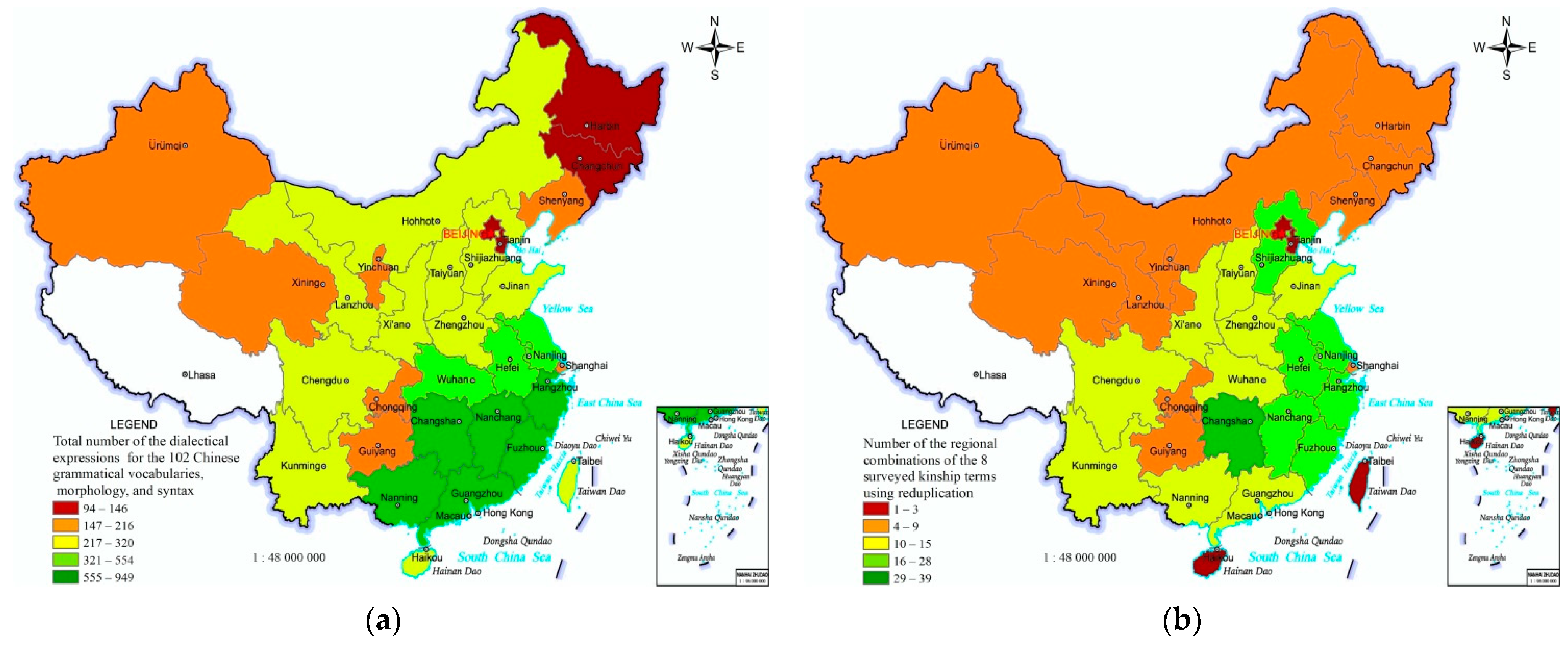

3.1. Diversity and Regional Differences of Chinese Dialects

3.2. China’s Regional Differences in Biodiversity

3.3. The Regional Correlation between Biodiversity and Linguistic Diversity of China

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Types of Surveyed Items | Surveyed Items |

|---|---|

| Initial, 77 | Development of Qièyùn voiced obstruent initials, voiced obstruent initials, evelopment of qièyùn voiced fricative initials, voiced fricative initials, nasal and lateral initials, [ɓ ɗ ɠ] initials, [tʂ tʂh ʂ] initials, [ɬ] initial, comparison of the initials in băi, pāi, & bái, the initials in pái, bèi, bìng, and bái, the initials in băo and bàn, the initials in mĭ, the initials in feī, fēng, and fú, the initial in wèn, comparison of the initials in fŭ & hŭ, the initials in duì and dēng, the initials in tàn, the initials in tong, the distinction between the qièyùn dental nasal and lateral initials, comparison of the initials in năo & lăo and nán & lán, comparison of the initials in ní & lí and nián & lián, the initials in lí, the initials in zăo, the initials in zuò, the initials in xiào, the initials in sān, the initials in cí and xiè, the distinction between the qièyùn dental sibilant and velar initials before high front vowels, comparison of the initials in jiŭ (wine) and jiŭ (nine), comparison of the initials in xuĕ and xuè, comparison of the initials in jiāng (starch), zhāng and jiāng (ginger), comparison of the initials in quán (complete), chuán and quán (authority), the initials in zhū, chōu, and chóng, the initials in shŏu, the initials in rè, the initials in ruăn, the initials in zhuān, the initials in shū, comparison of the initials in zhāng (sheet), zhuāng and zhāng (seal), comparison of the initials in shān & shàn, comparison of the initials in chāo & căo, comparison of the initials in shī & sī, the initials in jiē, the initials in kè, the initials in kāi, the initials in qiáo, the initials in áo, the initials in yín, the initials in xì, the initials in hòu, the initials in xiàn, comparison of the initials in huáng & wáng, the initials in ēn, the initials in wēn, the initials in yŭ, the initials in yuán, the initials in yán, the initials in yòng, the initials in pŭ, the initials in niăo, the initials in tong, the initials in tà, the initials in nòng, the initials in què, the initials in song, the initials in shì, the initials in chăn, the initials in shŭ, the initials in gū, the initials in gōu, the initials in jīn, the initials in jìn, the initials in qù, the initials in xī, the initials in guì, the initials in xióng, the initials in qiān. |

| Final, 84 | Development of nasal codas in finals, the codas [m n η], nasalized finals, development of final with oral stop codas, the codas [p t n l ʔ], development of qièyùn codas * -m and * -p, the codas in sān and chā, the codas in xīn and shí, the codas in shān and shā, the codas in xīn and qī, the codas in xiăng and xuē, the codas in shuāng and xué, the codas in shēng and sè, the codas in chéng and chĭ, the codas in zhōng and zhú, the final in dà, comparison of the finals in gē & guò, comparison of the finals in guò & gŭ, comparison of the finals in gē & gāo, the final in chē, comparison of the finals in xiě & xié, comparison of the finals in zhū & zhŭ, comparison of the finals in jù & qū, the finals in shū, comparison of the finals in lù & loú, comparison of the finals in chū & choū, the final in kāi, comparison of the finals in dài (bag) & dài (belt), the final in ăi, comparison of the finals in pái & pài, comparison of the finals in dài & pái, the final in tì, the final in mèi, the final in léi, comparison of the finals in jī & jì, comparison of the finals in zhĭ & shī, the finals in pí, dì, xì and yī, the finals in fēi, the final in shuĭ, the finals in guĭ, the finals in hăo, comparison of the finals in băo (treasure) & băo (satiated), comparison of the finals in xiào & diào, the final in dòu, comparison of the finals in lóu & liú, comparison of the finals in fú & fŭ, comparison of the finals in nán & lán, comparison of the finals in jiē & tiē, comparison of the finals in sān & shān, comparison of the finals in tán & tang, the final in lín, comparison of the finals in xīn (heart) & xīn (new), comparison of the finals in shēn & sheng, comparison of the finals in xīn & xīng, comparison of the finals in miàn (face, surface) & miàn (wheat flour), the final in bàn, the final in suān, comparison of the finals in hàn & guan, the final in gēn, the final in cùn, the final in sŭn, comparison of the finals in gŭn & gong, comparison of the finals in yún & yòng, the final in tang, the final in yào, comparison of the finals in kāng & jiăng, comparison of the finals in táng & lěng, comparison of the finals in shuāng & chóng, the final in dēng, the final in sè, comparison of the finals in bīng (ice) & bīng (soldier), the final in zhēng, the final in xīng, comparison of the finals in dēng & dōng and yĭng & yòng, the final in hóng, the final in fēng, the final in long, the final in zú, comparison of the finals in zhōng & zhŏng, comparison of the finals in zhú (bamboo) & zhú (candle), the final in hái, the final in dă, the final in gěng, finals with a high front rounded vowel as medial or main vowel, medials, apical vowels. |

| Tone, 38 | Tonal distribution of contrasting codas, number of tone categories, division of the Píng tone, division of the Shăng tone, division of the Qù tone, division of the Rù tone, tonal distribution of qièyùn voiceless unaspirated and aspirated initials, tonal distribution of qièyùn voiced and sonorant initials, merges of píng tone sonorants, merges of shăng tone voiced obstruents, merges of shăng tone sonorants, merges of qù tone sonorants, development of the rù tone, merges of rù tone voiceless obstruents, merges of rù tone voiced obstruents, merges of rù tone sonorants, tone of pitch-contour of dōng, tone of pitch-contour of tong, tone of pitch-contour of zhŏng, tone of pitch-contour of zuò, tone of pitch-contour of dòng, tone of pitch-contour of shù, tone of pitch-contour of bĕi, tone of pitch-contour of băi, tone of pitch-contour of dú, comparison of the tone in tóng with dŏng & dòng, comparison of tones in zuò & dà, comparison of tones in bĕi & băi, the tone of ting, the tone of aó, the tone of maō, the tone of long, the tone of nóng, the tone of Bing, the tone of pài, the tone of caō, the tone of bí, the tone of lā, nasal and lateral syllabics. |

| Combination of initial and final and other specials, 4 | The initial and final in chá, the initial and final in wú, the initial and final in ér, nasal and lateral syllabics. |

| Types | Surveyed Chinese Vocabularies |

|---|---|

| Nouns, 95 | Sun, Moon, thunder, rainbow, hail (noun), today, tomorrow, last year, rice (the plant), wheat straw, corn (the plant), meal/powder, sweet potato, potato, peanut, fava bean, radish, Chili pepper, eggplant, tomato, sunflower (the plant), boar (used for breeding), sow (that has farrowed), pigsty, dog, egg (of a chicken), monkey, tiger, rat/mouse, snake, bird, nest (of a bird), person, child, guest, paternal grandfather (direct address), paternal grandmother (direct address), maternal grandfather (direct address), maternal grandmother (direct address), father (direct address), mother (direct address), aunt (mother’s brother’s wife, direct address), husband (direct address), wife (direct address), sun (direct address), daughter in law (direct address), daughter (direct address), sun in law (direct address), head (of a human), face, eye(s), nose, mouth (of a human), tongue, neck, left hand, right hand, fist, foot, belly (abdomen), buttocks, excrement, penis, terms for “penis” derived from animal names, semen, breasts (of a woman), clothes, sleeve, steamed buns (unstuffed), steamed buns (stuffed), cooked dishes, euphemisms for pig’s tongue, euphemisms for pig’s liver, vinegar, village, alley, house (one ~), room (one ~), window, heated brick bed, grave (a ~), older words for cement, pot, wok (for cooking), firewood, kitchen knife, chopsticks, table, bottle, lid/cap, comb, soap (for washing clothes), umbrella, thing, thing/matter/event, vulva. |

| Adjectives, 29 | Many, small, thick, wide (diameter) (the rope is ~), thin/narrow (diameter) (the rope is ~), tall (stature), short (stature), thick (depth) (the board is ~), thin (depth) (the board is ~), wide (the road is ~), narrow (the road is ~), curved, crooked (the road is ~), dense (the crops are planted ~ly), sparse (the crops are planted ~ly), bright (of light), black (the color), hot (of the weather), cold (of the weather), bland/insipid (this food is ~), painful (took a ~ fall), dry (the clothes are ~), late (come late), fat (of pigs), fat (of people), thin (of people and pigs), beautiful, pretty (she is ~), correct (the account was calculated ~ly), incorrect (the account was calculated ~ly), hungry, thirsty. |

| Verbs, 53 | Castrate (a boar), butcher (a pig), rain (verb), lay (an egg), fuck, wear (shoes), tie (shoelaces), take off (shoes), eat (a meal), drink (wine), pick up (food with chopsticks), pour (wine), boil (eggs), deep-fry (dough sticks), watch (television), smell (with the nose), say, call out (after him), cry, scold (someone), bite (the dog bites someone), hit, hold (a child) in one’s arms, uproot/pull out (a radish), grab (a theif), carry (a sedan chair), carry (with a shoulder pole), stand (up), squat (down), jump, step on (cow dung), walk, run, escape, wipe (one’s hands dry), chop down (a tree), bury, hide, put (the bowl on the table), fall (down), pick up, find, select, owe, give, want (I want this one), think, know, be afraid, play/have fun, take a bath, sleep, marry (a woman). |

| Numerals, 3 | One, two, twenty |

| Adverbs, 2 | Sharp (the knife is sharp), fast (it is ~er to take the bus than to walk) |

| Quantifiers, 10 | Measure word for people, measure word for pigs, measure word for dogs, measure word for trees, measure word for autos, measure word for matters, business, measure word for written characters, measure word for meals, measure word for basic monetary unit, dollars, measure word for ten cents. |

| Special vocabularies, 11 | Semantic range of wénzi (mosquito), comparison of terms for wàisūn (daughter’s son) & wàisheng (sister’s son), semantic range of shŏu (hand) and jiăo (foot), comparison of terms for lā (defecate) & sā (urinate), comparison of terms for hē (drink) & chī (eat), semantic range of fáng (house), semantic range of wū (room), semantic range of cháng (long), semantic range of xì (thin), comparison of terms for pàng & feí (terms for fat), idioms referring to “the Moon” as a person. |

| Map Types | Surveyed Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Maps of Structures, 51 | Maps of standard Chinese forms, 29 | The suffix in zhuōzi (table), perfective aspect with substantive object (wŏ chī le yī wăn fàn, I ate a bowl of rice), the passive construction (wăn bèi tā dă pòle, bowl is broken by him), the negative comparative (wŏ meíyou tā dà, I am not elder than him), the noun suffix ér (including rhotacized forms), the suffix in jiàohuāzi (beggar), the suffix in niăoer (bird), suffixes derived from kinship terms, perfective aspect le1 and sentence particle le2 (tā laíle sān tiān le, he has been here for three days), perfective aspect le without object (tā laíle, he is coming), progressive aspect (he is having dinner), continuous aspect, the existing progressive zhe, potential complement dé, potential complement bùdé, the result complement qĭ lái in nĭ zhàn ~ (stand up), word order in bùzhīdào (don’t know),word order qù in wŏ măi cài ~ (I’m am going food shopping), the order of object and affirmative potential complement (dă de guò tā, beat him), the order of object and negative potential complement (dă bū guò tā, can’t beat him),the order of object and directional complement (xià kāi yŭ le, it’s raining),the order of object and quantity complement (jiào tā yī shēng, call him), word order in nĭ xiān qù (you go first), word order in zài chī yīwăn (have another bowl [of rice]), the disposal construction (tā bă wăn dă pòle,he broken the bowl), double-object imperative constructions (gěi wŏ yī zhī bĭ, give me a pen/pencil), the comparative (wŏ bĭ tā dà, I am elder than him), qù bū qù ? affirmative-negative question (míng tiān nĭ ~, will you go tomorrow ?), qù méi qù ? affirmative-negative question for the perfective aspect (zuó tiān nĭ ~, did you go yesterday ?) |

| Maps of Dialect Forms, 22 | Measure words as demonstratives, the noun suffix jiăn, xiān as postposition marking preceding action in nĭ qù ~ (you go first), degree adverb hĕn (very) in post adjective position, the familiarizing prefix ā used in names, the familiarizing prefix ā used in kinship terms, the kinship prefix lăo, the prefix gē, the noun suffix tóu, the suffix tóu used to denote monetary amounts, the noun suffixes zăi and zăi, reduplicated single-syllable nouns, reduplicated single-syllable verbs wènwen (ask), reduplicated single-syllable verbs with complements nĭkànkanqīngchŭ (look at this clearly), reduplicated single-syllable adverbs of extent (jīn tiān hěn hěn rè, it is very hot today), the result complement diao in jī sĭ ~ le (the chicken died), Yŏu as perfective verbal prefix in wŏ ~ qù (I went), zhe as postposition marking complement of one action as prerequisite to another in xiē yīhuìr ~ zài shuō (rest a bit and then decide), tiān as postposition marking additional action in chī yīwăn ~ (have another bowl [of rice]), tiān as postposition marking remaining quantity in hái yŏu shílĭ lù ~ (there are still 10 miles to go), guò as postposition marking repetition in huàn yījiàn ~ (change into another item [of clothing]), kàn as postposition marking a try in wènwen ~ (try asking) | |

| Maps of Grammatical Words, 39 | First-person singular pronoun wŏ (I) (~ xìng wáng, my family name is wáng),Second-person singular pronoun nĭ (You),Third-person singular pronoun tā (he, she), First-person plural pronoun (inclusive of listener) zánmen (we), the quantifier liă (two people), attributive of acquaintance of wŏ bà (my dad), reflective pronoun zìjĭ (myself), demonstrative pronoun zhè (this), demonstrative pronoun nà (that), interrogative personal pronoun nă (which), interrogative personal pronoun shuí (who), interrogative pronoun shénme (what), interrogative quantity pronoun duōshăo (how many/much), interrogative adverb zĕnme (how), degree adverb hĕn (very) for adjectives, degree adverb hĕn (very) in post adjective position, the plain negative bù (not), the possessive particle de, prefixes with the connotation “foreign”as yáng, the pronoun dàjiā (everybody), emonstratives as sentence subject, degree adverb hĕn (very) in extent complement construction, degree adverb zuì (most) for adjectives, the adverb of immediately jiù (then), the adverb yòu (again), the adverb yĕ (also), the adverb fănzhèng (in any case), the negative perfective méiyŏu (did not), the comparative marker bĭ (wŏ ~ tā dà, I am elder than him), the existential negative méiyŏu (does not have), the negative imperative bié (donʼt), the preposition cóng (from), verb of location zài (to be in, at, on), locative preposition zài (in, at, on), locative complement zài (into, onto), the copula shì (to be), the nominal conjunction hé (and), he locative suffix shàng, the disposal marker bă (~ yīfu shōu huílai, take the clothes back), the passive marker bèi (yīfu ~ tōu zŏule, clothes are stolen) | |

| Maps of Summary, 12 | Plural forms of personal pronouns, the pronoun dàjiā (everybody), negative word types, negative morpheme types, diminunatives, animal gender constructions, demonstrative pronoun types, the copula shì (to be) used as locative, kinship terms using reduplication, comparison of grammatical markers gěi, bă & bèi, comparison of particles used for imminent aspect and completed aspect, affirmative potential complement, negative potential complement | |

References

- Vejleskov, H. Social and intellectual functions of language: A fruitful distinction? J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 1988, 9, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, J.E. Literature and the social functions of language: Critical notes on an African debate. Crit. Arts South-North Cult. Media Stud. 1996, 10, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.H. Current Understanding of the Social Functions of Languages; Social Sciences in China: Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 159–171. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.W.; Zhang, J.W. Re-understanding of the correlation between linguistic diversity and socioeconomic development. Appl. Linguist. 2020, 19, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, D. Linguistic Diversity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gorenflo, L.J.; Romaine, S. Linguistic diversity and conservation opportunities at UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Africa. Conserv. Biol. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, H.H. Ecological approaches in linguistics: A historical overview. Lang. Sci. 2014, 41, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, L. Improving Language Learning by Addressing Students’ Social and Emotional Needs. Hispania 2021, 104, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.K.; Hasnain, S.I. Linguistic diversity and biodiversity. Lingua 2017, 195, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromham, L.; Hua, X.; Algy, C.; Meakins, F. Language endangerment: A multidimensional analysis of risk factors. J. Lang. Evol. 2020, 5, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mufwene, S.S. The Ecology of Language Evolution; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo, G.; Lusia, M.; Larsen, P.B. Indigenous and Traditional Peoples of the World and Ecoregion Conservation: An Integrated Approach to Conserving the World’s Biological and Cultural Diversity; WWF International-Terralingua: Gland, Switzerland, 2000; Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.382.2524 (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Gorenflo, L.J.; Romaine, S.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Walker-Painemila, K. Co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity in biodiversity hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8032–8037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romaine, S.; Gorenflo, L.J. Linguistic diversity of natural UNESCO world heritage sites: Bridging the gap between nature and culture. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 1973–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tershy, B.R.; Shen, K.W.; Newton, K.M.; Holmes, N.D.; Croll, D.A. The importance of islands for the protection of biological and linguistic diversity. Bioscience 2015, 65, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Steffensen, S.V.; Huang, G.W. Rethinking ecolinguistics from a distributed language perspective. Lang. Sci. 2020, 80, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeVasseur, T. Defining “Ecolinguistics?”: Challenging emic issues in an evolving environmental discipline. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2015, 5, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.A.K. New ways of meaning: The challenge to applied linguistics. J. Appl. Linguist. 1990, 6, 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, S. The birth of language ecology: Interdisciplinary influences in Einar Haugen’s “The ecology of language”. Lang. Sci. 2015, 50, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, E. On the Ecology of Languages. In Talk Delivered at a Conference at Burg Wartenstein, Austria, 1970; Haugen E. The Ecology of Language; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, E. The Ecology of Language; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.W.; Hu, Y.M.; Xiao, D.N. Landscape ecology and biodiversity conservation. Acta Ecol. Sin. 1999, 19, 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.Z.; Zhao, Y.X. Ecology and Biodiversity; Shandong Science and Technology Press: Jinan, China, 2013. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The Biodiversity Committee of Chinese Academy of Sciences. Catalogue of Life China: 2021 Annual Checklist; The Biodiversity Committee of Chinese Academy of Sciences: Beijing, China, 2021; Available online: http://sp2000.org.cn/statistics/statistics_map (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Yan, Y.Z.; Jarvie, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.S.; Han, P.; Liu, Q.F.; Liu, P.T. Small patches are hotspots for biodiversity conservation in fragmented landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.H.; Zhang, Z.X.; Huang, X.; Dao, B.; Zou, J.Y. Minority language. In Language Altas of China, 2nd ed.; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.Q.; Cao, J.H.; Shao, S. Linguistic diversity and regional openness disparity in China. J. World Econ. 2017, 40, 144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, G.; Suzuki, H. Tibet’s minority languages: Diversity and endangerment. Mod. Asian Stud. 2018, 52, 1227–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.H.; Miyata, I. Large Dictionary of Chinese Dialects; Chung Wha Book Company, Limited: Beijing, China. (In Chinese)

- Cao, Z.Y. Phonetics. In Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.Y. Lexicon. In Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.Y. Grammar. In Linguistic Atlas of Chinese Dialects; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke, J.; Kossowski, T. Comparison of values of Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients on the same sets of data. Quaest. Geogr. 2011, 30, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arndt, S.; Turvey, C.; Andreasen, N.C. Correlating and predicting psychiatric symptom ratings: Spearman’s r versus Kendall’s tau correlation. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1999, 33, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.K.; Hu, Z.Y.; Huang, X. The Languages of China; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2007. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.S. Literature review on modern Chinese dialects. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Suzhou 1999, 31, 24–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, K.D. When Languages Die: The Extinction of the World’s Languages and the Erosion of Human Knowledge; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Frainer, A.; Mustonen, T.; Hugu, S.; Andreeva, T.; Arttijeff, E.M.; Arttijeff, I.S.; Brizoela, F.; Coelho-de-Souza, G.; Printes, R.B.; Prokhorova, E.; et al. Cultural and linguistic diversities are underappreciated pillars of biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26539–26543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J. Vanishing voices: The extinction of the world’s languages. Hum. Ecol. 2002, 30, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.Y. Chinese dialects: Integration or multiplicity? Lang. Teach. Linguist. Stud. 2006, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.L. A Geographical Study of Lexicon of Shandong Dialect; Shandong University: Jinan, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Provinces (Including Autonomous Regions, Municipalities, and Special Administrative Regions) | Totalnumber of Animal And Plant Species | Total Number of Plant Species | Total Number of Animal Species | Number of Dialect Slices | Total Number of Variants of the 160 Phonologies, Pronunciations of the 32 Special Characters, and the 13 Important Phonetic Values of Chinese Dialects * | Total Number of the Dialectical Expressions for the 203 Chinese Words | Total Number of the Dialectical Expressions for the 102 Chinese Grammatical Vocabularies, Morphology, and Syntax | Number of the Regional Combinations of the Division of the Rù Tone | Number of the Dialectical Expressions for the Chinese Word “Father” | Number of the Regional Combinations of the 8 Surveyed Kinship Terms Using Reduplication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heilongjiang Province | 6153 | 2882 | 3271 | 3 | 242 | 143 | 146 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Jilin Province | 5486 | 2837 | 2649 | 2 | 226 | 151 | 144 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Liaoning Province | 6042 | 2831 | 3211 | 5 | 263 | 166 | 158 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region | 6387 | 3363 | 3024 | 8 | 437 | 221 | 227 | 7 | 5 | 8 |

| Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region | 8688 | 4617 | 4071 | 4 | 353 | 176 | 162 | 6 | 5 | 9 |

| Hebei Province | 6409 | 3183 | 3226 | 7 | 593 | 300 | 302 | 7 | 6 | 20 |

| Beijing City | 3530 | 715 | 2815 | 3 | 228 | 137 | 141 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Tianjin City | 1236 | 364 | 872 | 1 | 215 | 94 | 94 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Shanxi Province | 4994 | 2711 | 2283 | 9 | 710 | 272 | 269 | 12 | 6 | 14 |

| Shaanxi Province | 9140 | 5054 | 4086 | 8 | 647 | 323 | 320 | 8 | 6 | 11 |

| Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region | 3233 | 1511 | 1722 | 5 | 352 | 188 | 177 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Gansu Province | 8975 | 5358 | 3617 | 5 | 495 | 268 | 261 | 5 | 6 | 9 |

| Qinghai Province | 5223 | 2996 | 2227 | 2 | 311 | 148 | 167 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Shandong Province | 4761 | 2419 | 2342 | 8 | 578 | 260 | 287 | 9 | 9 | 13 |

| Henan Province | 5573 | 3138 | 2435 | 6 | 487 | 258 | 249 | 4 | 7 | 13 |

| Jiangsu Province | 5321 | 3006 | 2315 | 5 | 1069 | 408 | 502 | 7 | 9 | 22 |

| Shanghai City | 1968 | 579 | 1389 | 1 | 382 | 153 | 216 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Anhui Province | 5506 | 3701 | 1805 | 14 | 1289 | 460 | 554 | 10 | 18 | 22 |

| Hubei Province | 9034 | 5542 | 3492 | 6 | 889 | 373 | 397 | 6 | 17 | 15 |

| Chongqing City | 3587 | 2282 | 1305 | 3 | 257 | 186 | 184 | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| Sichuan Province | 22,724 | 13,494 | 9230 | 3 | 394 | 289 | 237 | 2 | 13 | 11 |

| Zhejiang Province | 10,524 | 5073 | 5451 | 10 | 1705 | 634 | 949 | 4 | 22 | 28 |

| Fujian Province | 10,947 | 5473 | 5474 | 6 | 1745 | 682 | 824 | 9 | 21 | 18 |

| Jiangxi Province | 7725 | 4843 | 2882 | 15 | 1707 | 598 | 731 | 9 | 16 | 24 |

| Hu’nan Province | 9201 | 5588 | 3613 | 15 | 1958 | 694 | 809 | 11 | 19 | 39 |

| Guizhou Province | 12,200 | 8204 | 3996 | 5 | 342 | 219 | 214 | 4 | 7 | 9 |

| Yunnan Province | 31,572 | 19,957 | 11,615 | 4 | 459 | 240 | 247 | 2 | 6 | 14 |

| Guangdong Province | 12,110 | 7387 | 4723 | 11 | 1537 | 739 | 856 | 8 | 19 | 11 |

| Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region | 14,937 | 9557 | 5380 | 8 | 1466 | 718 | 805 | 11 | 22 | 14 |

| Henan Province | 11,350 | 5186 | 6164 | 5 | 676 | 275 | 226 | 8 | 8 | 1 |

| Taiwan Province | 17,539 | 6992 | 10,547 | 2 | 564 | 227 | 269 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | 3847 | 1622 | 2225 | 1 | 303 | 139 | 142 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Macao Special Administrative Region | 1156 | 601 | 555 | 1 | 203 | 95 | 98 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chinese Dialect District | Sub-Dialect District | Dialect Slices | Population (×104 Capita) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin district | Northeastern Mandarin sub-district | 3 | 9802 |

| Beijing Mandarin sub-district | 2 | 2676 | |

| Ji-Lu Mandarin sub-district | 3 | 8942 | |

| Jiao-Liao Mandarin sub-district | 3 | 3495 | |

| Zhongyuan Mandarin sub-district | 13 | 18,648 | |

| Lan-Yin Mandarin sub-district | 4 | 1690 | |

| Jianghuai Mandarin sub-district | 3 | 8605 | |

| Southwestern Mandarin sub-district | 6 | 26,000 | |

| Jin Dialect district | 8 | 6305 | |

| Wu Dialect district | 6 | 7379 | |

| Min Dialect district | 8 | 7500 | |

| Hakka Dialect district | 8 | 4220 | |

| Cantonese Dialect district | 7 | 5882 | |

| Hunan Dialect district | 5 | 3637 | |

| Gan Dialect district | 9 | 4800 | |

| Hui Dialect district | 5 | 330 | |

| Pinghua and Tuhua Dialect district | 4 | 778 |

| Indicators of Biodiversity | Spearman Correlation Coefficient and the Two-Sided Test Confidence (Sig.) | Number of the Kinds of Chinese Slices | Total Number of Variants of the 160 Phonologies, Pronunciations of the 32 Special Characters, and the 13 Important Phonetic Values of Chinese Dialects | Total Number of the Dialectical Expressions for the 203 Chinese Words | Total Number of the Dialectical Expressions for the 102 Chinese Grammatical Vocabularies, Morphology, and Syntax | Number of the Regional Combinations of the Division of the Rù Tone | Number of the Dialectical Expressions for the Chinese Word “Father” | Number of the Regional Combinations of the 8 Surveyed Kinship Terms Using Reduplication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of plant and animal species | Spearman correlation coefficient | 0.370 * | 0.542 ** | 0.623 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.402 * | 0.628 ** | 0.397 * |

| Two-sided test confidence (Sig.) | 0.030 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.022 | |

| Number of plant species | Spearman correlation coefficient | 0.434 * | 0.600 ** | 0.688 ** | 0.624 ** | 0.463 ** | 0.706 ** | 0.477 ** |

| Two-sided test confidence (Sig.) | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.005 | |

| Number of animal species | Spearman correlation coefficient | 0.283 | 0.458 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.328 | 0.515 ** | 0.291 |

| Two-sided test confidence (Sig.) | 0.111 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.062 | 0.002 | 0.100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Bu, Z.; Ju, H.; Jing, Y. Investigation on the Relationship between Biodiversity and Linguistic Diversity in China and Its Formation Mechanism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095538

Zhang X, Bu Z, Ju H, Jing Y. Investigation on the Relationship between Biodiversity and Linguistic Diversity in China and Its Formation Mechanism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(9):5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095538

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xuliang, Zhanting Bu, Hongrun Ju, and Yibo Jing. 2022. "Investigation on the Relationship between Biodiversity and Linguistic Diversity in China and Its Formation Mechanism" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 9: 5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095538

APA StyleZhang, X., Bu, Z., Ju, H., & Jing, Y. (2022). Investigation on the Relationship between Biodiversity and Linguistic Diversity in China and Its Formation Mechanism. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095538