Attitudes toward Suicide and the Impact of Client Suicide: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Materials

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide in the World Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, S. Epidemiology of Suicide and the Psychiatric Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cerel, J.; Brown, M.M.; Maple, M.; Singleton, M.; Venne, J.; van de Moore, M.; Flaherty, C. How Many People Are Exposed to Suicide? Not Six. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutin, N.; McGann, V.L.; Jordan, J.R. The impact of suicide on professional caregivers. In Grief after Suicide: Understanding the Consequences and Caring for the Survivors; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, B.; Gitlin, D.; Patel, R. The depressed patient and suicidal patient in the emergency department: Evidence-based management and treatment strategies. Emerg. Med. Pract. 2011, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.J.; Norman, R.E.; Freedman, G.; Baxter, A.J.; Pirkis, J.E.; Harris, M.G.; Page, A.; Carnahan, E.; Degenhardt, L.; Vos, T.; et al. The Burden Attributable to Mental and Substance Use Disorders as Risk Factors for Suicide: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, J.B.; Martin, C.E.; Pearson, J.L. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, M.; Simmonds, J.G. Impact of Client Suicide on Psychologists in Australia. Aust. Psychol. 2018, 53, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, A.; O’Brien, S.; Phelan, D. Impact of patient suicide on consultant psychiatrists in Ireland. Psychiatrist 2010, 34, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothes, I.A.; Scheerder, G.; Van Audenhove, C.; Henriques, M.R. Patient suicide: The experience of Flemish psychiatrists. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2013, 43, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleespies, P.M.; Smith, M.R.; Becker, B.R. Psychology interns as patient suicide survivors: Incidence, impact, and recovery. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 1990, 21, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, L.; Sanders, S.; Jacobson, J.M.; Power, J.R. Dealing with the aftermath: A qualitative analysis of mental health social workers’ reactions after a client suicide. Soc. Work. 2006, 51, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dransart, D.A.C.; Gutjahr, E.; Gulfi, A.; Didisheim, N.K.; Séguin, M. Patient suicide in institutions: Emotional responses and traumatic impact on Swiss mental health professionals. Death Stud. 2014, 38, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, T.E.; Patel, A.B. Client suicide: What now? Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2012, 19, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.A.; Klein, S.; Gray, N.M.; Dewar, I.G.; Eagles, J.M. Suicide by patients: Questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2000, 320, 1571–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hendin, H.; Lipschitz, A.; Maltsberger, J.T.; Haas, A.P.; Wynecoop, S. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 2022–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Hallen, R. Suicide Exposure and the Impact of Client Suicide: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Arch. Suicide Res. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hallen, R.; Godor, B.P. Exploring the Role of Coping Strategies on the Impact of Client Suicide: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. OMEGA J. Death Dying 2022, 302228211073213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, P.; Shaghaghi, A.; Allahverdipour, H. Measurement Scales of Suicidal Ideation and Attitudes: A Systematic Review Article. Health Promot. Perspect. 2015, 5, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbacher, M.; Domino, G. Attitudes toward Suicide among Attempters, Contemplators, and Nonattempters. OMEGA J. Death Dying 1986, 16, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, C.; Corcoran, P.; Keeley, H.S.; Perry, I.J. Risk of Suicide Ideation Associated with Problem-Solving Ability and Attitudes Toward Suicidal Behavior in University Students. Crisis J. Crisis Interv. Suicide Prev. 2003, 24, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stein, D.; Witztum, E.; Brom, D.; DeNour, A.K.; Elizur, A. The association between adolescents’ attitudes toward suicide and their psychosocial background and suicidal tendencies. Adolesc. Rosl. Heights 1992, 27, 949–959. [Google Scholar]

- Pitman, A.; Nesse, H.; Morant, N.; Azorina, V.; Stevenson, F.; King, M.; Osborn, D. Attitudes to suicide following the suicide of a friend or relative: A qualitative study of the views of 429 young bereaved adults in the UK. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagley, C.; Ramsay, R.F. Attitudes toward suicide, religious values and suicidal behavior. Evidence from a community survey. In Suicide and Its Prevention: The Role of Attitude and Imitation; Diekstra, R.F.W., Ed.; BRILL: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1989; pp. 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson, M.; Sunbring, Y.; Winell, I.; Åsberg, M. Nurses’ Attitudes to Attempted Suicide Patients. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 1997, 11, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werth, J.L.; Liddle, B.J. Psychotherapists’ attitudes toward suicide. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 1994, 31, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, B.J.; Domino, G. Attitudes toward suicide among mental health professionals. Death Stud. 1985, 9, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukouvalas, E.; El-Den, S.; Murphy, A.L.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; O’Reilly, C.L. Exploring Health Care Professionals’ Knowledge of, Attitudes Towards, and Confidence in Caring for P. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 24, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodaka, M.; Inagaki, M.; Poštuvan, V.; Yamada, M. Exploration of factors associated with social worker attitudes toward suicide. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2013, 59, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecz, P. Psychometric evaluation of the Questionnaire on Attitudes Towards Suicide (ATTS) in Poland. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 2528–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renberg, E.S.; Jacobsson, L. Development of a Questionnaire on Attitudes Towards Suicide (ATTS) and Its Application in a Swedish Population. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2003, 33, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, M.; Bell, R.; Failla, S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale—Revised. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Gulfi, A.; Castelli Dransart, D.A.; Heeb, J.-L.; Gutjahr, E. The impact of patient suicide on the professional reactions and practices of mental health caregivers and social workers. Crisis 2010, 31, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, P.J. Therapists’ psychological adaptation to client suicide. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 1994, 31, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Séguin, M.; Drouin, M.-S. Les réactions des professionnels en snaté mentale au décès par suicide d’un patient. [Mental health professionals’ response to the suicide of their patients.]. Rev. Québécoise De Psychol. 2004, 25, 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, R.D.; Valero-Mora, P.; Macbeth, G. The Scree Test and the Number of Factors: A Dynamic Graphics Approach. Span. J. Psychol. 2015, 18, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, C.-C.; Dai, C.-L.; Richardson, G.B. A call for, and beginner’s guide to, measurement invariance testing in evolutionary psychology. Evol. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 4, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; Kashy, D.A.; Bolger, N. Data analysis in social psychology. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 1–2, pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, G.; Pridmore, S. Suicide is preventable, sometimes. Australas. Psychiatry 2012, 20, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, L.; Jackson, K.; Harvey, D. Client suicidal behaviour: Impact, interventions, and implications for psychologists. Aust. Psychol. 2000, 35, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackelprang, J.L.; Karle, J.; Reihl, K.M.; Cash, R.E. Suicide intervention skills: Graduate training and exposure to suicide among psychology trainees. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2014, 8, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hawgood, J.; Krysinska, K.; Mooney, M.; Ozols, I.; Andriessen, K.; Betterridge, C.; De Leo, D.; Kõlves, K. Suicidology Post Graduate Curriculum: Priority Topics and Delivery Mechanisms for Suicide Prevention Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, S.; Wojciak, J.; Day, S. The impact of suicide on community mental health teams: Findings and recommendations. Psychiatr. Bull. 2002, 26, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanders, S.; Jacobson, J.M.; Ting, L. Preparing for the Inevitable: Training Social Workers to Cope with Client Suicide. J. Teach. Soc. Work. 2008, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlim, M.T.; Perizzolo, J.; Lejderman, F.; Fleck, M.P.; Joiner, T.E. Does a brief training on suicide prevention among general hospital personnel impact their baseline attitudes towards suicidal behavior? J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 100, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oordt, M.S.; Jobes, D.A.; Fonseca, V.P.; Schmidt, S.M. Training mental health professionals to assess and manage suicidal behavior: Can provider confidence and practice behaviors be altered? Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2009, 39, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaney, P.H. Affect and memory: A review. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 99, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frissa, S.; Hatch, S.L.; Fear, N.T.; Dorrington, S.; Goodwin, L.; Hotopf, M. Challenges in the retrospective assessment of trauma: Comparing a checklist approach to a single item trauma experience screening question. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roemer, L.; Litz, B.T.; Orsillo, S.M.; Ehlich, P.J.; Friedman, M.J. Increases in retrospective accounts of war-zone exposure over time: The role of PTSD symptom severity. J. Trauma. Stress 1998, 11, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.M.; Morgan, C.A.; Nicolaou, A.L.; Charney, D.S. Consistency of memory for combat-related traumatic events in veterans of Operation Desert Storm. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wessely, S.; Unwin, C.; Hotopf, M.; Hull, L.; Ismail, K.; Nicolaou, V.; David, A. Stability of recall of military hazards over time: Evidence from the Persian Gulf War of 1991. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 183, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fairman, N.; Montross Thomas, L.P.; Whitmore, S.; Meier, E.A.; Irwin, S.A. What Did I Miss? A Qualitative Assessment of the Impact of Patient Suicide on Hospice Clinical Staff. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| 14. | People do have the right to take their own lives. | 0.760 | |

| 02. | Suicide can never be justified. (R) | 0.741 | |

| 09. | I would consider the possibility of taking my life if suffering from a severe, incurable disease. | 0.720 | |

| 11. | A person suffering from disease expressing wishes to die should get help to do so. | 0.693 | |

| 13. | I can understand that people suffering from a severe, incurable disease commit suicide. | 0.688 | |

| 07. | There may be situations where the only reasonable resolution is suicide. | 0.671 | |

| 15. | I would like to get help to commit suicide if I were to suffer from a severe, incurable disease. | 0.636 | |

| 12. | I am prepared to help a person in a suicidal crisis by making contact. | 0.601 | |

| 08. | Although you would prefer to die in a different way, encountering painful life circumstances could make you consider suicide. | 0.565 | |

| 18. | Suicides among young people are particularly puzzling since they have everything to live for. | ||

| 17. | Suicide should not always be prevented. | ||

| 10. | If someone wants to commit suicide it is their business and we should not interfere. (R) | 0.774 | |

| 04. | Once a person has made up their mind about suicide no one can stop them. (R) | 0.670 | |

| 05. | It is a human duty to try to stop someone from committing suicide. | 0.665 | |

| 16. | Suicide can be prevented. | 0.651 | |

| 03. | Committing suicide is among the worst things to do to one’s relatives. | 0.515 | |

| 06. | Loneliness could for me be a reason to take my life. (R) | 0.471 | |

| 01. | It is always possible to help a person with suicidal thoughts. | ||

| Unstandardized Estimate | Standard Error | Standardized Estimate | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

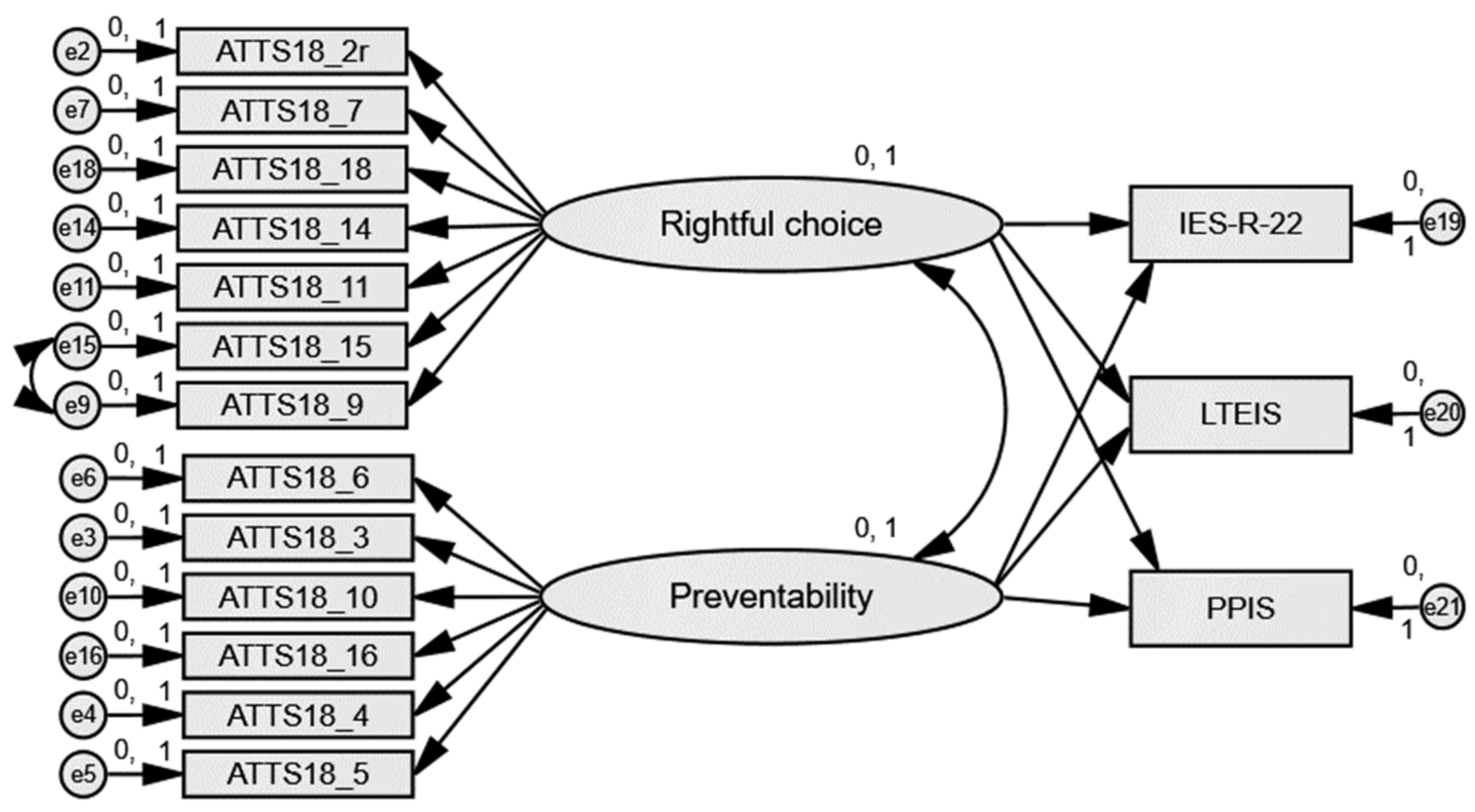

| Rightful Choice | IES-R | −6.020 | 1.734 | −0.314 | <.001 |

| Rightful Choice | LTEIS | −0.199 | 0.083 | −0.217 | .017 |

| Rightful Choice | PPIS | −0.135 | 0.065 | −0.187 | .037 |

| Preventability | IES-R | 8.019 | 1.778 | 0.418 | <.001 |

| Preventability | LTEIS | 0.266 | 0.085 | 0.291 | .002 |

| Preventability | PPIS | 0.290 | 0.067 | 0.401 | <.001 |

| Unstandardized Estimate | Standard Error | Standardized Estimate | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

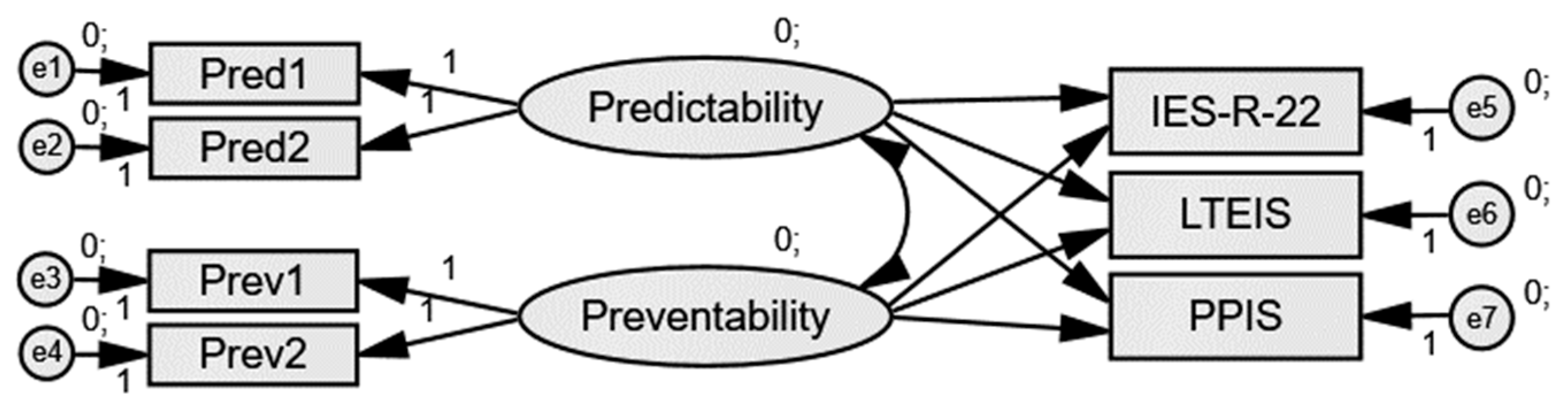

| Predictability | IES-R | −88.962 | 73.257 | −2.432 | .225 |

| Predictability | LTEIS | −5.288 | 4.242 | −3.038 | .213 |

| Predictability | PPIS | −4.050 | 3.301 | −2.940 | .220 |

| Preventability | IES-R | 177.257 | 135.131 | 2.540 | .190 |

| Preventability | LTEIS | 10.217 | 7.818 | 3.076 | .191 |

| Preventability | PPIS | 7.992 | 6.089 | 3.040 | .189 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pisnoli, I.; Van der Hallen, R. Attitudes toward Suicide and the Impact of Client Suicide: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095481

Pisnoli I, Van der Hallen R. Attitudes toward Suicide and the Impact of Client Suicide: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(9):5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095481

Chicago/Turabian StylePisnoli, Irene, and Ruth Van der Hallen. 2022. "Attitudes toward Suicide and the Impact of Client Suicide: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 9: 5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095481

APA StylePisnoli, I., & Van der Hallen, R. (2022). Attitudes toward Suicide and the Impact of Client Suicide: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095481