Resilience in the Perinatal Period and Early Motherhood: A Principle-Based Concept Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

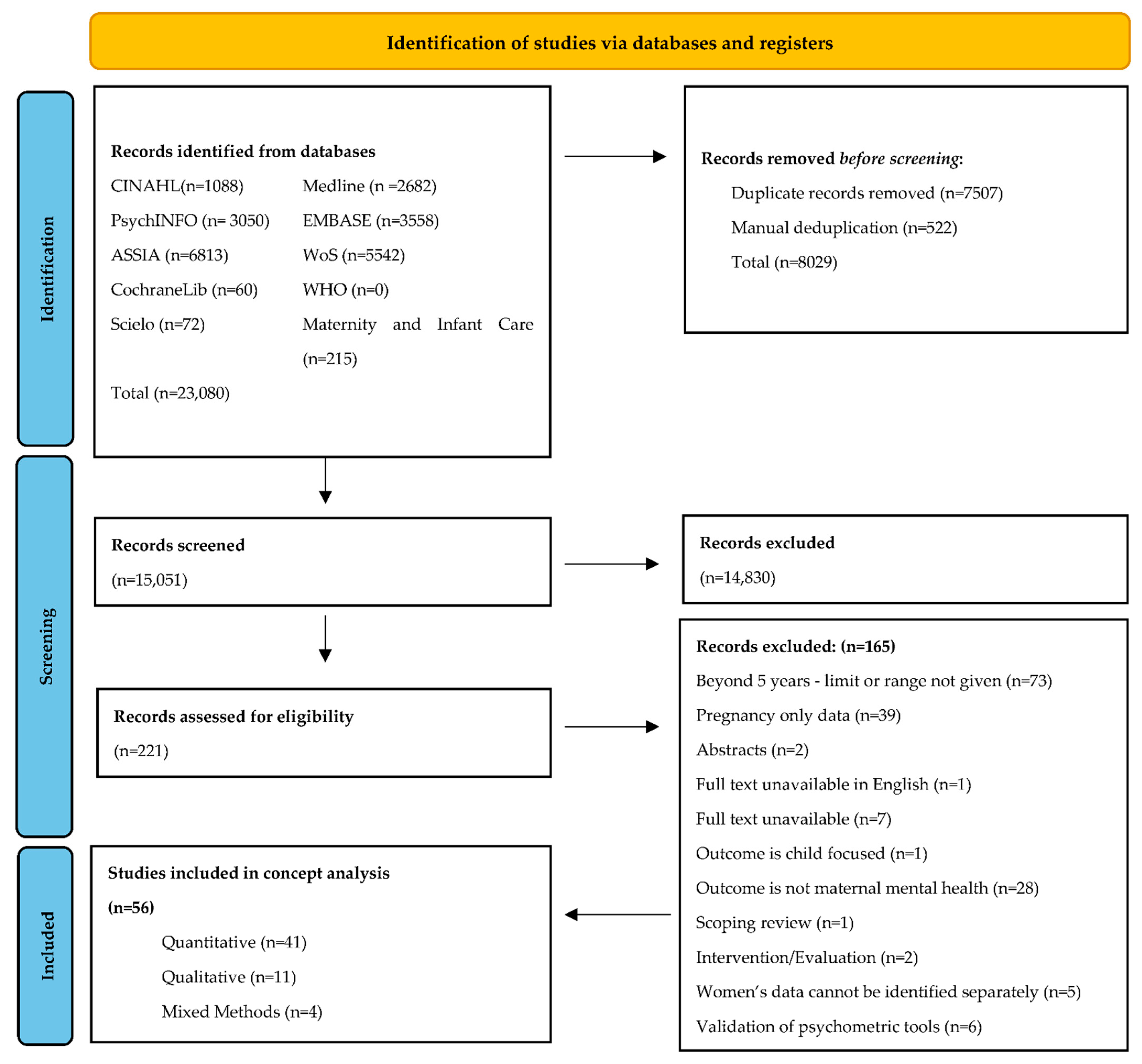

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Epistemological Principle: Key Findings

Definitional Elements

| Quantitative Designs | Resilience Operationalised | ||||||||

| Mental Ill-Health | |||||||||

| Author, Discipline | Country, Characteristics of Sample | Resilience Definition | Resilience Scales | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | PTSD | Other | Well-Being or Positive Functioning |

| Andersson et al. (2021) [73] Computer Science. | Sweden. 4313 postpartum women from a population-based prospective cohort study. Data collected at 6 weeks postpartum (PP). | No formal definition | Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA) [88] | X | X | X | Sense of Coherence | ||

| Angeles García-León et al. (2019) [40] Psychology. | Spain. 151 pregnant women with low-risk pregnancy. Data collected in third trimester and approximately 15 days PP. | Trait/ability | Spanish translation of the CD-RISC (CD-RISC-10) [89] | X | X | X | Psychological Well-being | ||

| Asif et al. (2020) [49] Medicine. | Sweden. Sub-sample (n = 2026/6478) women. Data collected at 17 and 32 weeks gestation and 6 weeks PP. | Trait/ability | Resilience was operationalised by the sense of coherence scale (SOC) [90] | X | |||||

| Assal-Zrike et al. (2021) [79] Psychology. | Israel. Fifty-seven mothers of full-term infants and 48 mothers of preterm infants. Mothers were ethnic minority Bedouin-Arabs living in Israel. Data collected at 12 months PP. | No formal definition | Investigate the role of social support as a resilience factor for reduced postpartum emotional distress. | X | X | X | |||

| Asunción et al. (2016) [75] Psychology. | Mexico. 280 low-income Mexican mothers aged ≥20 years. Data collected in pregnancy (>26 weeks) and at 6 weeks and 6 months PP. | No formal definition | Resilience Inventory (RESI) [91] | X | X | X | |||

| Bennett et al. (2018) [41] Human Nutrition. | Ireland. 270 Irish and British women giving birth in Ireland. Data collected in pregnancy (>24 weeks) and at 17 weeks PP. | Trait/ability | Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA) [88] | X | * Maternal Well-Being | ||||

| Chasson et al. (2021) [50] Social Work. | Israel. 152 first-time Israeli mothers, whose children were no older than two years old; 76 were single mothers by choice, and 76 were in a couple relationship. | Trait/ability | Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) [92] | X | Posttraumatic Growth | ||||

| Denckla et al. (2018) [70] Public Health. | England. Data available from 12,121 women at two points during pregnancy and at 8 months and 2, 3, and 5 years PP. | No formal definition | Resilience was operationalised as a trajectory of stable, low levels of depressive symptoms. | X | |||||

| Fonseca et al. (2014) [69] Psychology. | Portugal. 43 couples (43 mothers and 36 fathers), aged ≥18 years, literate, with an infant diagnosed with a congenital abnormality (CA). Data collected at time of CA diagnosis and 6 months after the childbirth. | Operational definition: ‘Maintenance of healthy adjustment over time, without disruption of functioning’ (p. 113) | Resilience was operationalised as low psychological distress and high quality of life. | X | Quality of Life | ||||

| Gagnon et al. (2013) [58] Epidemiology and Public Health. | Canada. 16 international migrant women (aged 27–38 years) participants had high psychosocial risk (low income, experience of violence, war or trauma, physical abuse). Data collected between 1 week and 4 months PP. | Dynamic process | Resilience was operationalised as low depression, no symptoms of anxiety/somatization or PTSD. | X | X | X | |||

| Gerstein et al. (2009) [59] Psychology. | USA.115 families with a child with an intellectual disability between three and five years of age. | Dynamic process | Effects of parental wellbeing, marital adjustment, parent-child interaction (resilience factors) on trajectories of daily parenting stress (resilience outcome). | X | * Parental Well-Being | ||||

| Grote et al. (2007) [60] Psychology. | USA. 179 married first-time parents. Data collected at five months of pregnancy and 6 and 12 months PP. | Dynamic process | ‘Risk and resilience’ theoretical framework to examine the degree to which optimism (resilience factor) conferred protection against PPD (resilience outcome). | X | X | ||||

| Hain et al. (2016) [93] Psychology. | Germany. 297 women (aged 20–45 years). Data collected in the third trimester of pregnancy and at 6 and 12 weeks PP. | Both trait and process definitions | The RS-11 (Resilienzskala) [94] | X | X | X | X | ||

| Handelzalts et al. (2020) [76] Psychology. | USA. Subset (n = 108/268) of women recruited from a longitudinal study oversampled for women who reported childhood abuse. Data collected at 4, 6, 12, and 15 months PP. | No formal definition | Religiosity and spirituality as resiliency factors for positive postpartum adjustment (resilience outcome) defined as low depression and high QoL. | X | Maternal Quality of Life | ||||

| Harville et al. (2010) [80] Epidemiology. | USA. 295 pregnant women (222 completed) and 365 postpartum (eight weeks) women (292 completed) living in Louisiana who were exposed to Hurricane Katharina. | No formal definition | Resilience was operationalised as low depression and low/no PTSD. | X | X | Perceived Benefits:Personal Growth (single item) | |||

| Harville et al. (2011) [42] Epidemiology. | USA. 365 mothers exposed to multiple disasters. Data collected via phone interview at 2 months PP and survey questionnaire at 12 months PP. | Trait/ability | Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) [92] | X | X | Perceived Benefit | |||

| Julian et al. (2021) [51] Psychology. | USA. 233 ethnically diverse women from a prospective longitudinal study. Resilience resource data were collected during pregnancy and depressive symptoms were assessed between 4 to 8 weeks PP | Trait/ability | Moderating role of mastery, dispositional optimism, and spirituality (resilience resources) against the impact of stressful life events occurring in pregnancy and subsequent symptoms of PPD. | X | |||||

| Kikuchi et al. (2021) [71] Psychiatry. | Japan. Sub-sample (n = 11, 668/22,493) women. Women were recruited in pregnancy and depressive symptoms assessed at 1 month and 1 year PP. | Operational definition: ‘not depressed throughout 1 year postpartum’. (p. 632) | Resilience was operationalised as a trajectory of depressive symptomology absence. | X | |||||

| Ladekarl et al. (2021) [35] Obstetrics and Gynaecology. | Denmark. 73 women enrolled during pregnancy before (n = 26) and during (n = 47) the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected in the second trimester and at two months PP. | Trait/ability | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | X | |||

| Liu et al. (2020) [36] Mental Health. | USA. 506 postpartum women taking part in the PEACE (Perinatal Experiences and COVID-19 Effects) study. Data were collected online within 6 months PP. | No formal definition | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | X | X | ||

| Margalit et al. (2006) [43] Psychology. | Israel. 70 mothers from ‘intact families’ with infants aged 2–39 months and diagnosed as at-risk for delayed development. | Trait/ability | Resilience was operationalised using the sense of coherence scale (SOC) [90] | X | Family Adaptability and Cohesion, Coping | ||||

| Martinez-Torteya et al. (2018) [44] Psychology. | USA. Sub-sample (n = 131/256) of women from a longitudinal study over sampled for women who reported childhood abuse. Data collected at 4 and 6 months PP. | Trait/ability | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | Parenting Sense of Competence | ||||

| Mautner et al. (2013) [45] Psychology. | Austria. 67 women German-speaking women who were diagnosed with preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy, and who gave birth within the last four years. | Trait/ability | The RS-13 [96] | X | X | Health Related Quality of Life | |||

| McNaughton Reyes et al. (2020). [78] Health Behaviour. | South Africa. 1480 pregnant women who recently became aware of their HIV positive status in South Africa. Participants were recruited in pregnancy and data collected at 14 weeks and 9 months PP. | No formal definition | Moderating role of socio-economic status, family social support, religiosity, or a vulnerability effect: baseline distress, childhood abuse history, HIV diagnosis (resiliency factors) on the long-term impact of physical/sexual IPV exposure and subsequent postpartum distress. | X | |||||

| Mikuš et al. (2021) [52] Obstetrics and Gynecology. | Croatia. 227 puerperal women giving birth in Croatia. Data collected on day 3 PP. | Trait/ability | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | |||||

| Miranda et al. (2012) [77] Psychology. | Brazil. 52 women with low socioeconomic status who experienced a preterm birth 6–12 months prior to the study. | No formal definition | Resilience was operationalised as low depressive symptoms and/or low PPD. | X | |||||

| Mitchell et al. (2011) [74] Social Science. | USA. 209 African American mothers (aged 21–45 years) of varying socioeconomic status, whose babies were two to 18 months old. | No formal definition | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | ||||

| Mollard et al. (2021) [37] Nursing. | USA. 885 women who gave birth in the USA during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. | Trait/ability | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | Mastery | ||||

| Monteiro et al. (2020) [62] Psychology. | Portugal. 661 postpartum women with infants between 0 and 12 months. | Dynamic process | Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA) [88] | X | Mental Wellbeing, Maternal Confidence, Self-Compassion, Psychological Flexibility | ||||

| Muzik et al. (2016) [56] Psychiatry. | USA. Sub-sample (n = 116/256) of women from a longitudinal study over sampled for women who reported childhood abuse. Data collected at 4, 6, and 18 months PP. | Trait/ability | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | |||||

| Nishi et al. (2017) [46] Psychiatry. | Japan. 117 women (aged ≥20 years), Japanese speaking, and literate, recruited in pregnancy at 12–24 weeks gestation and assessment follow-up completed at 4 weeks PP. | Trait/ability | Tachikawa Resilience Scale (TRS) [97] | X | Post Traumatic Growth | ||||

| Perez et al. (2021) [72] Psychology. | USA. 70 mothers and 50 fathers, (data were separable) of a child diagnosed with a disorder/difference of sex development (DSD). Participants were recruited when their child was <2 years old. Data were collected prior to a child receiving genitoplasty, and at 6 and 12 months post-surgery. | No formal definition | Resilience was operationalised as a trajectory of ‘consistently low levels of (depression) symptoms across time.’ (p. 589). | X | |||||

| Puertas-Gonzalez et al. (2021) [38] Psychology. | Spain. 212 participants; 96 gave birth before the COVID-19 pandemic and 116 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected one month PP. | No formal definition | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | X | |||

| Sahin (2022) [53] Psychiatry. | Turkey. 120 women recruited in pregnancy. 120 completed assessment during pregnancy, and 77 women completed assessment one month PP. | Trait/ability | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | Maternal Attachment | |||

| Schachman et al. (2013). [61] Psychology. | USA. 71 women married to (but were not themselves active-duty service women) active-duty military members stationed at a USA military base, delivered a singleton live baby within 3 months of the study. | Dynamic process | Effects of family changes and strains, self-reliance, social support (protective factors) on postpartum depression (outcome). | X | Family Changes and Strains, Self-Reliance, Social Support | ||||

| Sexton et al. (2016) [47] Psychology. | USA. Sub-sample (n = 141/256) of women from a longitudinal study over sampled for women who reported childhood abuse. Data collected at 4 months PP. | Trait/ability | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | Family Specific Well-Being, Postpartum Mastery | |||

| Sexton et al. (2015) [48] Psychology. | USA. Sub-sample (n = 214/256) of women from a longitudinal study over sampled for women who reported childhood abuse. Data collected at 4 months PP. | Trait/ability | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | Family Functioning, Postpartum Sense of Competence | |||

| Verstraeten et al. (2021) [68] Obstetrics and Gynecology. | Canada. 200 women who experienced a wildfire in Canada during, or shortly before, pregnancy. Women were recruited within one year of the wildfire. | Both trait and process definitions | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | ||||

| Werchan et al. (2022) [39] Cognitive Science. | USA. Data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic from 4412 pregnant and postpartum (within first 12 PP months) women used to identify risk and protective/resiliency factors associate with four behavioural coping phenotype profiles. | No formal definition | Research identified coping phenotypes or profiles associated with risk and resiliency for adverse mental and physical health outcomes. | X | X | X | |||

| Yu et al. (2020) [54] Public Health. | China. 1126 women recruited in pregnancy from two urban maternal and child health hospitals in Hunan province, China. Data were collected at four time points (3 times during pregnancy and at 6 weeks PP). | Trait/ability | Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) [92] | X | X | X | |||

| Zhang et al. (2021) [55] Gynecology and Obstetrics. | China. 200 pregnant women admitted to hospital for preterm labour. Postpartum PTSD was evaluated at 6 weeks PP. | Trait/ability | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | ||||

| Mixed-Methods Designs | Resilience Operationalised | ||||||||

| Author, Discipline | Country, Characteristics of Sample | Resilience Definition | Resilience Scales | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | PTSD | Other | Well-Being or Positive Functioning |

| Davis et al. (2021) [32] Mental Health. | Australia. Sub-sample (n = 174/461) of perinatal women living through the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. | Trait/ability | Resilience was operationalised through scales measuring mindfulness and self-compassion. | X | Mental Well-being | ||||

| A stratified sub-sample (n = 14/174) completed the qualitative component. | Qualitative Findings: Interviews conducted with seven women from the ‘high’ resilience group and seven from the ‘low’ resilience group. Both groups identified the social, emotional, psychological, healthcare service, and informational needs of perinatal women during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||||||||

| Farewell et al. (2020) [33] Health and Behavioural | USA. 31 pregnant and postpartum women (within 6 months PP), living in Colorado, during the COVID-19 pandemic. | No formal definition | Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) [92] | X | X | X | Mental Well-being | ||

| Sciences. | Qualitative Findings: Sources of resilience identified by participants included using virtual communication platforms, having positive partner emotional support, being outdoors, focusing on gratitude, setting daily routines, and self-care behaviours, such as engaging in physical activity, getting adequate sleep and eating well. | ||||||||

| Kinser et al. (2021). [34] Nursing. | USA. Mixed-methods research with 524 pregnant and postpartum (up to 6 months PP) women. Data were collected | Trait/ability | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [95] | X | X | X | |||

| during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. | Qualitative Findings: Adaptability and resilience building activities were defined as: taking time to get outdoors, getting exercise and eating well, use of mindfulness practices and meditation, use of prayer, using social media for connection with family and friends, and accepting help. | ||||||||

| Edge and Roger (2005). [81] Epidemiology. | England. Theoretic sampling of 12, inner city, Black-Caribbean women for in-depth interviews at 6–12 months PP. | No formal definition | The authors presented resilience under the narrative of ‘Strong-Black-Women’. An identity theme characterised by an active resistance to symptomatology and labelling, with resilience being linked to coping and problem solving. Quantitative data were not reported. | ||||||

| Qualitative Designs | Resilience Operationalised | ||||||||

| Author, Discipline | Country, Characteristics of Sample | Resilience Definition | |||||||

| Farewell et al. (2021). [85] Health and Behavioural Sciences. | New Zealand. 74 mothers of children under the age of five, living in a high deprivation neighbourhood in Auckland, NZ. Data were collected via one-to-one interviews and focus groups. | No formal definition | ‘Protective factors’ and ‘resources’ were presented as promoting resilience/positive mental health and well-being in this research. The researchers developed a priori codes hypothesised to promote resilience among mothers across ethnic groups. Themes linked to socioecological resources that support positive mental health and well-being included: (1) social support: support from family and friends offering emotional and instrumental support. (2) community level: neighbourhood cohesion, community involvement, community resources. (3) societal-level factors: cultural identity and alignment with social and cultural norms. | ||||||

| Gewalt et al. (2018). [82] Public Health. | Germany. Nine asylum-seeking women (aged 22–37 years) living in state provided accommodation. Interview data collected at two points during pregnancy and at 6 weeks PP. | No formal definition | Authors interpret social support and coping styles as factors that increase resilience and act as counterbalances to psychosocial stressors. | ||||||

| Goodman et al. (2020). [65] Obstetrics and Gynecology. | USA. Ten women in New England who had entered treatment for opioid use disorder during pregnancy, and engaged in treatment in the postpartum period. Data were collected in interviews between 2 weeks and 1 year PP. | Dynamic process | Within data collected in semi-structured interviews with women with opioid use disorder, who continued to engage in treatment during the postpartum period, the theme of resilience was identified by the researchers as emerging and developing as an adaptive and dynamic process. Resilience was considered evident through complex interactions between individual-level inner motivations and self-efficacy, and women’s abilities to positively utilise external resources such as engagement with clinicians and peers. | ||||||

| Keating-Lefler and Wilson. (2004). [57] Nursing Science. | USA. 20 single, first time mothers, Medicaid-eligible, and living in poverty. Recruited in pregnancy and interviewed at 1, 2, and 3 months PP. Aged ≥19 years, English-speaking. | Trait/ability | Authors position qualitative findings within a grief framework; resilience was considered integral to the negotiation of ‘multiple losses’ experienced by un-partnered mothers, and held within the theme of ‘reformulating life’. | ||||||

| Keating-Lefler et al. (2004). [84] Nursing Science. | USA. 5 single mothers with and infant less than 1 year, low income, not living with child’s father, and attending a women, infants, and children clinic. | No formal definition | Resilience was a subtheme of ‘transition’, though resilience and its attributes were undefined by this study. | ||||||

| Nuyts et al. (2021). [87] Midwifery/ Epidemiology. | Belgium. Purposive sample of 13 women without pre-existing bipolar and psychotic disorders or a depressive or anxiety disorder, admitted to an infant mental health outpatient service in Belgium when their infant was aged 1 to 24 months. | Dynamic process | Data concerned the professional support needs of mothers prior to admission to an infant mental health day clinic. The three themes identified were ‘experience of pregnancy, birth, and parenthood’; ‘difficult care paths’; and ‘needs and their fulfilment’. The theme ‘experience of pregnancy, birth, and parenthood’ contained three subthemes: (1) ‘reality does not meet expectations’, (2) ‘resilience under pressure’, and (3) ‘despair’. The theme ‘resilience under pressure’ was not developed, and the term resilience appeared interchangeable with ‘mental health’. | ||||||

| Rossman et al. (2016). [63] Nursing Science. | USA. Socio-economic and ethnically diverse subsample (n = 23/69) of mothers of very-low birth weight infants derived from a study on maternal role attainment. Qualitative interview data collected between 4 and 8 weeks PP. | Dynamic process | Characteristics considered demonstrative of resilience were mothers using resources to actively promote their mental health, reframing or redefining their lives, acceptance of reality, advocating for their infants, positive functioning in daily life, and envisioning the future. | ||||||

| Schaefer et al. (2019) [64] Psychology. | USA. Racially diverse sample of 10, low-income women who experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) during or immediately prior to pregnancy and had given birth within the last year, and 46 service providers who interacted directly with women exposed to IPV in pregnancy. | Dynamic process | Authors identified the overarching theme of ‘strengths’, which was comprised of ‘transformation’ and ‘resilience’. ‘Strengths’ were understood as character traits possessed by pre- and postpartum mothers exposed to IPV around pregnancy. Resilience was considered demonstrated through women’s continued efforts to access individual resources and seek community support. | ||||||

| Shadowen et al. (2022) [86] Obstetrics and Gynaecology. | USA. 8 postpartum women receiving medication for opioid use disorder. Data were collected between 2 and 6 months PP. | No formal definition | The researchers identified the theme of ‘building resilience amidst trauma and pain’ within the qualitative data provided by postpartum women receiving medication for opioid use disorder. ‘Building resilience’ was linked with themes of transformation and perseverance in overcoming traumatic experiences and stigma as part of their recovery journey. | ||||||

| Shaikh et al. (2010) [83] Sociology. | Canada. 12 women (aged 24–39 years), residing in underserviced rural communities, with a psychiatric diagnosis of Postpartum Depression (PPD), or who self-identified as having suffered from PPD within one year after birth and no more than five years prior to the study. | No formal definition | Authors equated resilience with ‘coping strategies leading to successful adaptation or positive outcomes under stressful or adverse circumstances.’ (p. 3). Coping strategies were identified using four theoretical components: Existential philosophy: meaning making strategies; Cultural relational theory: seeking support; Feminist standpoint theory: nurturing oneself and advocacy work; Beyond theoretical framework: connecting with nature. | ||||||

| Theodorah et al. (2021) [66] Nursing. | South Africa. Qualitative interviews with 10 first-time mothers within the first six months PP. | Dynamic process | Two themes and subthemes were identified: (1) ‘challenges, empowerment, support, and resilience during initiation of exclusive breastfeeding’ –subcategory: ‘support and resilience during early breastfeeding (EBF) initiation; (2) ‘diverse support and resilience during maintenance of exclusive breastfeeding’—subcategory: ‘support and resilience during EBF maintenance’. Differences between categories were not well specified and themes of resilience were not developed. | ||||||

3.2. Linguistic Principle: Key Findings

3.3. Pragmatic Principle: Key Findings

3.3.1. Operationalisation and Research Pragmatism

3.3.2. Stakeholders’ Interpretations of Resilience in the Context of the Perinatal Period and Early Motherhood

3.3.3. Clinical Pragmatism:

3.4. Logical Principle: Key Findings

3.4.1. Mental Health

3.4.2. Adaptation and Adjustment

3.4.3. Coping

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manderscheid, R.W.; Ryff, C.D.; Freeman, E.J.; McKnight-Eily, L.R.; Dhingra, S.; Strine, T.W. Evolving definitions of mental illness and wellness. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2010, 7, A19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.M. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadephul, F.; Glover, L.; Jomeen, J. Conceptualising women’s perinatal well-being: A systematic review of theoretical discussions. Midwifery 2020, 81, 102598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phua, D.Y.; Kee, M.Z.L.; Meaney, M.J. Positive Maternal Mental Health, Parenting, and Child Development. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S.S. Mothering mothers. Res. Hum. Dev. 2015, 12, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S.S.; Ciciolla, L. Who mothers mommy? Factors that contribute to mothers’ well-being. Dev. Psych. 2015, 51, 1812–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windle, G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2011, 21, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, S.; Zimmerman, M.A. Adolescent Resilience: A Framework for Understanding Healthy Development in the Face of Risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2004, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.; Becker, B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leys, C.; Arnal, C.; Wollast, R.; Rolin, H.; Kotsou, I.; Fossion, P. Perspectives on resilience: Personality Trait or Skill? J. Trauma. Dissociation 2020, 4, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornor, G. Resilience. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2017, 31, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aburn, G.; Gott, M.; Hoare, K. What is resilience? An Integrative Review of the empirical literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 980–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J. A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 76, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossion, P.; Leys, C.; Kempenaers, C.; Braun, S.; Verbanck, P.; Linkowski, P. Disentangling Sense of Coherence and Resilience in case of multiple traumas. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 160, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur. Psych. 2013, 18, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H.; Stewart, D.E.; Diaz-Granados, N.; Berger, E.L.; Jackson, B.; Yuen, T. What is Resilience? Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanyes Truffino, J. Resilience: An approach to the concept. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud. Men 2010, 3, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbilt-Adriance, E.; Shaw, D.S. Conceptualizing and Re-Evaluating Resilience Across Levels of Risk, Time, and Domains of Competence. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusaie, K.; Dyer, J. Resilience: A historical review of the construct. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2004, 18, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earvolino-Ramirez, M. Resilience: A Concept Analysis. Nurs. Forum 2007, 42, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Dia, M.J.; DiNapoli, J.M.; Garcia-Ona, L.; Jakubowski, R.; O’Flaherty, D. Concept analysis: Resilience. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2013, 27, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, C.A.; Bond, L.; Burns, J.M.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A.; Sawyer, S.M. Adolescent resilience: A concept analysis. J. Adolesc. 2003, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, D.M.; Stewart, R.; Ritchie, K.; Chaudieu, I. Resilience and mental health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmitorz, A.; Kunzler, A.; Helmreich, I.; Tüscher, O.; Kalisch, R.; Kubiak, T.; Wessa, M.; Lieb, K. Intervention studies to foster resilience-A systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 59, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrod, J.; Hupcey, J.E. Enhancing methodological clarity: Principle-based concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.O.; Avant, K.C. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing; Pearson/Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, B.L. Concepts, analysis and the development of nursing knowledge: The evolutionary cycle. J. Adv. Nurs. 1989, 14, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, B.L.; Knafl, K.A. Concept analysis: An evolutionary view. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques and Applications; Eoyang, T., Ed.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland, R.; Phares, V.; Thompson, J.K. Adolescent motherhood and postpartum depression. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2005, 34, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, D.; Higgins, A.V.S. Postpartum sexual health: A principle-based concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 2247–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.A.; Gibson, L.Y.; Bear, N.L.; Finlay-Jones, A.L.; Ohan, J.L.; Silva, D.T.; Prescott, S.L. Can Positive Mindsets Be Protective Against Stress and Isolation Experienced during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Emotional Health and Wellbeing Needs of Perinatal Women. Int. J. Environ. Res 2021, 18, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farewell, C.V.; Jewell, J.; Walls, J.; Leiferman, J.A. A Mixed-Methods Pilot Study of Perinatal Risk and Resilience During COVID-19. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinser, P.A.; Jallo, N.; Amstadter, A.B.; Thacker, L.R.; Jones, E.; Moyer, S.; Rider, A.; Karjane, N.; Salisbury, A.L. Depression, Anxiety, Resilience, and Coping: The Experience of Pregnant and New Mothers During the First Few Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladekarl, M.; Olsen, N.J.; Winckler, K.; Brødsgaard, A.; Nøhr, E.A.; Heitmann, B.L.; Specht, I.O. Early postpartum stress, anxiety, depression, and resilience development among danish first-time mothers before and during first-wave COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2021, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.H.; Koire, A.; Erdei, C.; Mittal, L. Unexpected changes in birth experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for maternal mental health. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollard, E.; Kupzyk, K.; Moore, T. Postpartum stress and protective factors in women who gave birth in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women’s Health 2021, 17, 17455065211042190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas-Gonzalez, J.A.; Mariño-Narvaez, C.; Romero-Gonzalez, B.; Peralta-Ramirez, M.I. Giving birth during a pandemic: From elation to psychopathology. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werchan, D.M.; Hendrix, C.L.; Ablow, J.C.; Amstadter, A.B.; Austin, A.C.; Babineau, V.; Bogat, G.A.; Cioffredi, L.A.; Conradt, E.; Crowell, S.E.; et al. Behavioral coping phenotypes and associated psychosocial outcomes of pregnant and postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles Garcia-Leon, M.; Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; Romero-Gonzalez, B.; Gonzalez-Perez, R.; Peralta-Ramirez, I. Resilience as a protective factor in pregnancy and puerperium: Its relationship with the psychological state, and with Hair Cortisol Concentrations. Midwifery 2019, 75, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.E.; Kearney, J.M. Factors associated with maternal wellbeing at four months post-partum in Ireland. Nutrients 2018, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harville, E.W.; Xiong, X.; Smith, B.W.; Pridjian, G.; Elkind-Hirsch, K.; Buekens, P. Combined effects of Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Gustav on the mental health of mothers of small children. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalit, M.; Kleitman, T. Mothers’ stress, resilience and early intervention. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2006, 21, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Torteya, C.; Katsonga-Phiri, T.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Hamilton, L.; Muzik, M. Postpartum depression and resilience predict parenting sense of competence in women with childhood maltreatment history. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2018, 21, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mautner, E.; Stern, C.; Deutsch, M.; Nagele, E.; Greimel, E.; Lang, U.; Cervar-Zivkovic, M. The impact of resilience on psychological outcomes in women after preeclampsia: An observational cohort study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishi, D.; Usuda, K. Psychological growth after childbirth: An exploratory prospective study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 38, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, M.B.; Muzik, M.; McGinnis, E.G.; Rodriguez, K.T.; Flynn, H.A.; Rosenblum, K.L. Psychometric Characteristics of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in Postpartum Mothers with Histories of Childhood Maltreatment. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2016, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, M.B.; Hamilton, L.; McGinnis, E.W.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Muzik, M. The roles of resilience and childhood trauma history: Main and moderating effects on postpartum maternal mental health and functioning. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 174, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, S.; Mulic-Lutvica, A.; Axfors, C.; Eckerdal, P.; Iliadis, S.I.; Fransson, E.; Skalkidou, A.; Mulic-Lutvica, A.; Iliadis, S.I. Severe obstetric lacerations associated with postpartum depression among women with low resilience-a Swedish birth cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 127, 1382–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasson, M.; Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. Personal growth of single mothers by choice in the transition to motherhood: A comparative study. J. Reprod. Infant. Psychol. 2021, 39, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, M.; Le, H.N.; Coussons-Read, M.; Hobel, C.J.; Dunkel Schetter, C. The moderating role of resilience resources in the association between stressful life events and symptoms of postpartum depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuš, M.; Škegro, B.; Sokol Karadjole, V.; Lešin, J.; Banović, V.; Herman, M.; Goluža, T.; Puževski, T.; Elveđi-Gašparović, V.; Vujić, G. Maternity Blues among Croatian Mothers-A Single-Center Study. Psychiatr. Danub. 2021, 33, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, B. Predicting Maternal Attachment: The Role of Emotion Regulation And Resilience During Pregnancy. J. Basic Clin. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Gong, W.J.; Taylor, B.; Cai, Y.Y.; Xu, D. Coping Styles in Pregnancy, Their Demographic and Psychological Influences, and Their Association with Postpartum Depression: A Longitudinal Study of Women in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2020, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, G.Y. Study on the correlation between posttraumatic stress disorder and psychological resilience in pregnant women with possible preterm labor. Int. J. Clin. Exp. 2021, 14, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Muzik, M.; Brier, Z.; Menke, R.A.; Davis, M.T.; Sexton, M.B. Longitudinal suicidal ideation across 18-months postpartum in mothers with childhood maltreatment histories. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 204, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Keating-Lefler, R.; Wilson, M.E. The experience of becoming a mother for single, unpartnered, Medicaid-eligible, first-time mothers. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2004, 36, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, A.J.; Carnevale, F.; Mehta, P.; Rousseau, H.; Stewart, D.E. Developing population interventions with migrant women for maternal-child health: A focused ethnography. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, E.D.; Crnic, K.A.; Blacher, J.; Baker, B.L. Resilience and the course of daily parenting stress in families of young children with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2009, 53, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Bledsoe, S.E. Predicting postpartum depressive symptoms in new mothers: The role of optimism and stress frequency during pregnancy. Health Soc. Work 2007, 32, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachman, K.; Lindsey, L. A resilience perspective of postpartum depressive symptomatology in military wives. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2013, 42, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, F.; Fonseca, A.; Pereira, M.; Canavarro, M.C. Is positive mental health and the absence of mental illness the same? Factors associated with flourishing and the absence of depressive symptoms in postpartum women. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 77, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, B.; Greene, M.M.; Kratovil, A.L.; Meier, P.P. Resilience in Mothers of Very-Low-Birth-Weight Infants Hospitalized in the NICU. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2017, 46, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, L.M.; Howell, K.H.; Sheddan, H.C.; Napier, T.R.; Shoemaker, H.L.; Miller-Graff, L.E. The Road to Resilience: Strength and Coping Among Pregnant Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 36, 8382–8408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, D.J.; Saunders, E.C.; Wolff, K.B. In their own words: A qualitative study of factors promoting resilience and recovery among postpartum women with opioid use disorders. BMC Preg. Child 2020, 20, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodorah, D.Z.; Mc’Deline, R.N. “The kind of support that matters to exclusive breastfeeding” a qualitative study. BMC Preg. Child 2021, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodin, D.; Stewart, D.E. Resilience in Elderly Survivors of Child Maltreatment. SAGE Open 2012, 2, 2158244012450293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, B.S.E.; Elgbeili, G.; Hyde, A.; King, S.; Olson, D.M. Maternal Mental Health after a Wildfire: Effects of Social Support in the Fort McMurray Wood Buffalo Study. Can. J. Psychiatry 2021, 66, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Nazare, B.; Canavarro, M.C. Parenting an infant with a congenital anomaly: An exploratory study on patterns of adjustment from diagnosis to six months post birth. Child Health Care 2014, 18, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denckla, C.A.; Mancini, A.D.; Consedine, N.S.; Milanovic, S.M.; Basu, A.; Seedat, S.; Spies, G.; Henderson, D.C.; Bonanno, G.A.; Koenen, K.C. Distinguishing postpartum and antepartum depressive trajectories in a large population-based cohort: The impact of exposure to adversity and offspring gender. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, S.; Murakami, K.; Obara, T.; Ishikuro, M.; Ueno, F.; Noda, A.; Onuma, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Sugawara, J.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. One-year trajectories of postpartum depressive symptoms and associated psychosocial factors: Findings from the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.N.; Clawson, A.H.; Baudino, M.N.; Austin, P.F.; Baskin, L.S.; Chan, Y.M.; Cheng, E.Y.; Coplen, D.; Diamond, D.A.; Fried, A.J.; et al. Distress Trajectories for Parents of Children With DSD: A Growth Mixture Model. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.; Bathula, D.R.; Iliadis, S.I.; Walter, M.; Skalkidou, A. Predicting women with depressive symptoms postpartum with machine learning methods. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.; Ronzio, C. Violence and Other Stressful Life Events as Triggers of Depression and Anxiety: What Psychosocial Resources Protect African American Mothers? Matern. Child Health J. 2011, 15, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asuncion Lara, M.; Navarrete, L.; Nieto, L. Prenatal predictors of postpartum depression and postpartum depressive symptoms in Mexican mothers: A longitudinal study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2016, 19, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handelzalts, J.E.; Stringer, M.K.; Menke, R.A.; Muzik, M. The Association of Religion and Spirituality with Postpartum Mental Health in Women with Childhood Maltreatment Histories. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.M.; Soares, C.N.; Moraes, M.L.; Fossaluza, V.; Serafim, P.M.; Mello, M.F. Healthy maternal bonding as a resilience factor for depressive disorder. Psychol. Neurosci. 2012, 5, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton Reyes, H.L.; Maman, S.; Groves, A.K.; Moodley, D. Intimate partner violence and postpartum emotional distress among South African women: Moderating effects of resilience and vulnerability factors. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assal-Zrike, S.; Marks, K.; Atzaba-Poria, N. Prematurity, maternal emotional distress, and infant social responsiveness among arab-bedouin families: The role of social support as a resilience factor. Child Dev. 2021, 93, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harville, E.W.; Xiong, X.; Buekens, P.; Pridjian, G.; Elkind-Hirsch, K. Resilience After Hurricane Katrina Among Pregnant and Postpartum Women. Women’s Health Issues 2010, 20, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, D.; Rogers, A. Dealing with it: Black Caribbean women’s response to adversity and psychological distress associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and early motherhood. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewalt, S.C.; Berger, S.; Ziegler, S.; Szecsenyi, J.; Bozorgmehr, K. Psychosocial health of asylum seeking women living in state-provided accommodation in Germany during pregnancy and early motherhood: A case study exploring the role of social determinants of health. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.; Kauppi, C. Coping Strategies as a Manifestation of Resilience in the Face of Postpartum Depression: Experiences of Women in Northern Ontario. Int. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Sci. 2010, 5, 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Keating-Lefler, R.; Hudson, D.B.; Campbell-Grossman, C.; Fleck, M.O.; Westfall, J. Needs, concerns, and social support of single, low-income mothers. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2004, 25, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farewell, C.V.; Quinlan, J.; Melnick, E.; Lacy, R.; Kauie, M.; Thayer, Z.M. Protective resources that promote wellbeing among new zealand moms with young children facing socioeconomic disadvantage. Women Health 2021, 61, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadowen, C.; Jallo, N.; Parlier-Ahmad, A.B.; Brown, L.; Kinser, P.; Svikis, D.; Martin, C.E. What Recovery Means to Postpartum Women in Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. Womens Health Rep. 2022, 3, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuyts, T.; Van Haeken, S.; Crombag, N.; Singh, B.; Ayers, S.; Garthus-Niegel, S.; Braeken, M.A.K.A.; Bogaerts, A. “Nobody listened”. Mothers’ experiences and needs regarding professional support prior to their admission to an infant mental health day clinic. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2021, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, G.M.; Young, H.M. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1993, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Notario-Pacheco, B.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Trillo-Calvo, E.; Pérez-Yus, M.C.; Serrano-Parra, D.; García-Campayo, J. Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the 10-item CD-RISC in patients with fibromyalgia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gaxiola, J.C.; Frías, M.; Hurtado, M.F.; Salcido, L.C.; Figueroa, M. Validation of the Resilience Inventory (RESI) in a northwestern Mexico sample. Enseñanza Investig. Psicol. 2011, 16, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hain, S.; Oddo-Sommerfeld, S.; Bahlmann, F.; Louwen, F.; Schermelleh-Engel, K. Risk and protective factors for antepartum and postpartum depression: A prospective study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 37, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J.; Leppert, K.; Gunzelrnann, T.; Strauß, B.; Brähler, E. Die Resilienzskala-Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der psychischen Widerstandsfähigkeit als Personmerkmal. The Resilience Scale-A questionnaire to assess resilience as a personality characteristic. Z. Klin. Psychol. Psychiatr. Psychother. 2005, 53, 16–39. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppert, K.; Koch, B.; Brähler, E.; Strauß, B. Die Resilienzskala RS–Überprüfung der Langform RS-25 und einer Kurzform RS-13. Klin. Diagn. Eval. 2008, 1, 226–243. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi, D.; Uehara, R.; Yoshikawa, E.; Sato, G.; Ito, M.; Matsuoka, Y. Culturally sensitive and universal measure of resilience for Japanese populations: Tachikawa Resilience Scale in comparison with Resilience Scale 14-item version. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 67, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosco, T.D.; Kaushal, A.; Hardy, R.; Richards, M.; Kuh, D.; Stafford, M. Operationalising resilience in longitudinal studies: A systematic review of methodological approaches. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, B.P.; Hammels, C.; Geschwind, N.; Menne-Lothmann, C.; Pishva, E.; Schruers, K.; van den Hove, D.; Kenis, G.; van Os, J.; Wichers, M. Resilience in mental health: Linking psychological and neurobiological perspectives. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013, 128, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høivik, M.S.; Burkeland, N.A.; Linaker, O.M.; Berg-Nielsen, T.S. The Mother and Baby Interaction Scale: A valid broadband instrument for efficient screening of postpartum interaction? A preliminary validation in a Norwegian community sample. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 27, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R. Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual National Computer Systems; BSI Brief Symptom Inventory: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sereda, Y.; Dembitskyi, S. Validity assessment of the symptom checklist SCL-90-R and shortened versions for the general population in Ukraine. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantz, I.; Eriksson, B.; Lundquist-Persson, C.; Ahlberg, B.M.; Nilstun, T. Screening for postpartum depression with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): An ethical analysis. Scand. J. Public Health 2008, 36, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Den, S.; O’Reilly, C.L.; Chen, T.F. A systematic review on the acceptability of perinatal depression screening. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 188, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, R.T. Becoming a mother versus maternal role attainment. J. Nurs. Sch. 2004, 36, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S.S.; Zelazo, L.B. Research on Resilience: An Integrative Review. In Resilience and Vulnerability: Adaptation in the Context of Childhood Adversities; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 510–549. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haeken, S.; Braeken, M.A.K.A.; Nuyts, T.; Franck, E.; Timmermans, O.; Bogaerts, A. Perinatal Resilience for the First 1000 Days of Life. Concept Analysis and Delphi Survey. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 563432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Dev. Psychopathol. 2000, 12, 857–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manwell, L.A.; Barbic, S.P.; Roberts, K.; Durisko, Z.; Lee, C.; Ware, E.; McKenzie, K. What is mental health? Evidence towards a new definition from a mixed methods multidisciplinary international survey. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S.S.; Zigler, E. Vulnerability and competence: A review of research on resilience in childhood. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1991, 61, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hannon, S.E.; Daly, D.; Higgins, A. Resilience in the Perinatal Period and Early Motherhood: A Principle-Based Concept Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084754

Hannon SE, Daly D, Higgins A. Resilience in the Perinatal Period and Early Motherhood: A Principle-Based Concept Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084754

Chicago/Turabian StyleHannon, Susan Elizabeth, Déirdre Daly, and Agnes Higgins. 2022. "Resilience in the Perinatal Period and Early Motherhood: A Principle-Based Concept Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084754

APA StyleHannon, S. E., Daly, D., & Higgins, A. (2022). Resilience in the Perinatal Period and Early Motherhood: A Principle-Based Concept Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084754