Effectiveness of the Biography and Life Storybook for Nursing Home Residents: A Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- Is there a difference in nursing home residents’ depression scores after receiving the BLSB intervention compared to those who participated in usual daily care?

- Is there a difference in nursing home residents’ life satisfaction scores after receiving the BLSB intervention compared to those who participated in usual daily care?

- Is there a difference in nursing home residents’ QoL scores after receiving the BLSB intervention compared to those who participated in usual daily care?

2.2. Settings and Participants

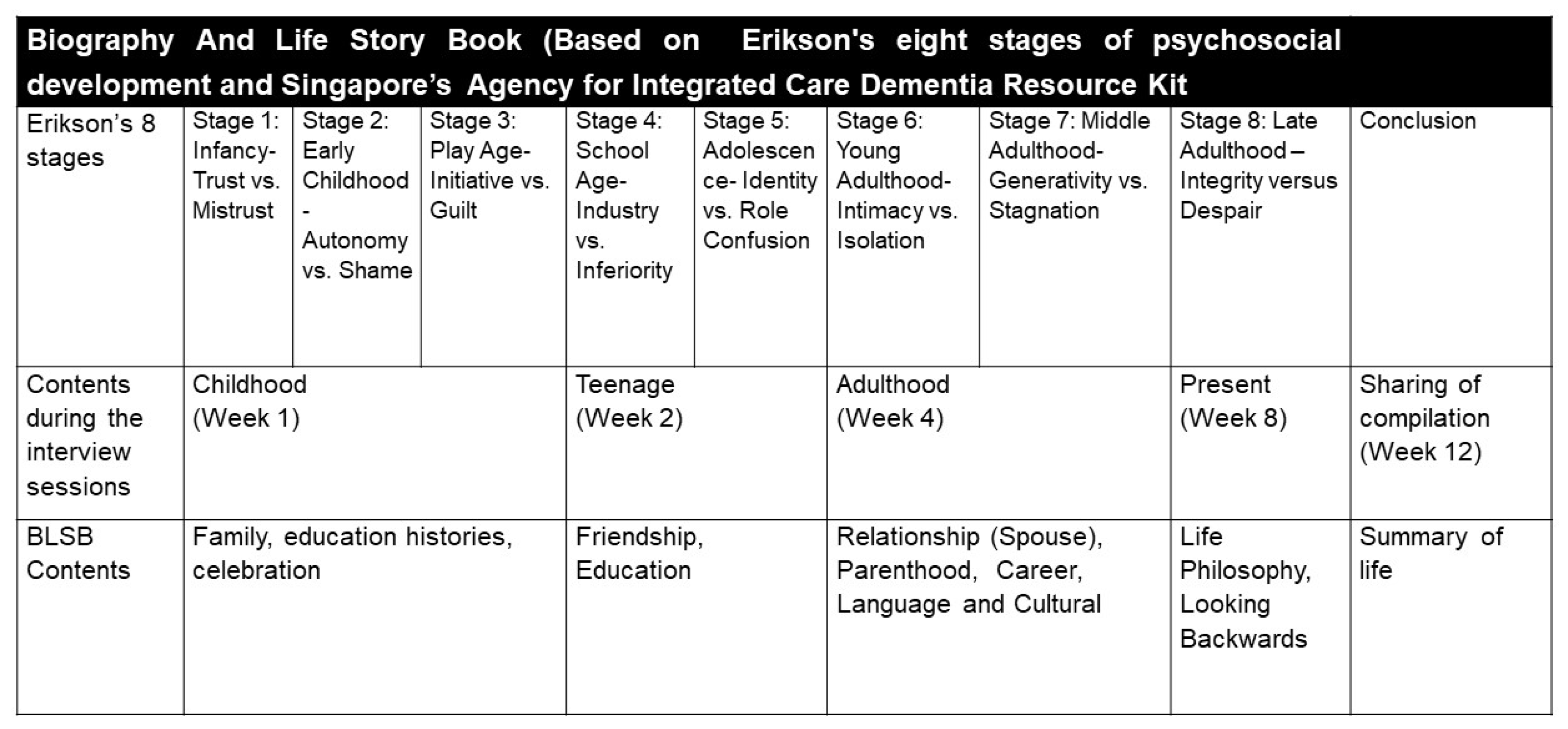

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

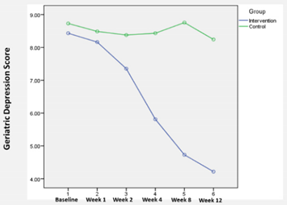

3.1. GDS-15 Depression Scores

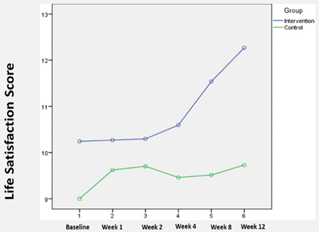

3.2. LSIA (Life Satisfaction) Scores

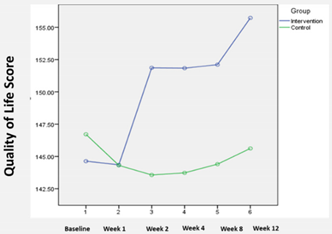

3.3. QoL (Quality of Life) Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parker, G.; Gridley, K.; Birks, Y.; Glanville, J. Using a systematic review to uncover theory and outcomes for a complex intervention in health and social care: A worked example using life story work for people with dementia. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2020, 25, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Ho, D.W.H.; Fung, K.; Tang, L.; He, M.; Young, K.W.; Ho, F.; Kwok, T. Effectiveness of a life story work program on older adults with intellectual disabilities. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindell, J.; Burrow, S.; Wilkinson, R.; Keady, J.D. Life story resources in dementia care: A review. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2014, 15, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Integrated Care. Knowing Dementia: A Resource Kit for Caregiver; Agency for Integrated Care: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, A.; Sousa, L.; Nolan, M.; Figueiredo, D. Effects of Person-Centered Care Approaches to Dementia Care on Staff: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 2015, 30, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, C.; Noonan, M.; Doody, O. Life story work in long term care facilities for older people: An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1070–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeown, J.; Clarke, A.; Repper, J. Life story work in health and social care: Systematic literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 55, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ghafri, B.R.; Al-Mahrezi, A.; Chan, M.F. Effectiveness of life review on depression among elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 40, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice, 9th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781609130046. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Rajaa, S.; Rehman, T. Diagnostic accuracy of various forms of geriatric depression scale for screening of depression among older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 87, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, L.E.; Yong, Y.Z.; Chng, M.W.X.; Chew, S.H.; Cheng, L.; Chua, Q.H.A.; Yek, J.J.L.; Lau, L.J.F.; Anand, P.; Hoe, J.T.M.; et al. Individual and area-level socioeconomic status and their association with depression amongst community-dwelling elderly in Singapore. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehregosha, M.; Bastaminia, A.; Vahidian, F.; Mohammadi, A.; Aghaeinejad, A.; Jamshidi, E.; Ghasemi, A. Life Satisfaction Index among Elderly People Residing in Gorgan and Its Correlation with Certain Demographic Factors in 2013. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2016, 8, 52103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutubaeva, R.Z. Analysis of life satisfaction of the elderly population on the example of Sweden, Austria and Germany. Popul. Econ. 2019, 3, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lan, X.; Xiao, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X. Effects of Life Review Intervention on Life Satisfaction and Personal Meaning Among Older Adults with Frailty. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2018, 56, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, R.L.; Bershadsky, B.; Kane, R.A.; Degenholtz, H.H.; Liu, J.J.; Giles, K.; Kling, K.C. Using resident reports of quality of life to distinguish among nursing homes. Gerontologist 2004, 44, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, F.; Lou, Y.; Zhou, W.; Tong, F. The Effectiveness of Reminiscence Therapy on Alleviating Depressive Symptoms in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 709853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, W.; Poon, S.N.; Mahendran, R.; Kua, E.H.; Wu, X.V. The effectiveness of reminiscence-based intervention on improving psychological well-being in cognitively intact older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 114, 103847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikmat, A.W.; Al-Mashoor, S.H.; Hashim, N.A. Quality of life in people with cognitive impairment: Nursing homes versus home care. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, W.W.; Yap, P.; Huat Koh, G.C.; Phoon Fong, N.; Luo, N. Prevalence and risk factors of depression in the elderly nursing home residents in Singapore. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 17, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.Y.; Tam, W.S.W.; Goh, H.S.; Ow, C.C.; Wu, X.V. Impact of sense of coherence, resilience and loneliness on quality of life amongst older adults in long-term care: A correlational study using the salutogenic model. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 4471–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, E.; Devane, D.; Cooney, A.; Casey, D.; Jordan, F.; Hunter, A.; Murphy, E.; Newell, J.; Connolly, S.; Murphy, K. The impact of reminiscence on the quality of life of residents with dementia in long-stay care. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 29, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sáez, E.; Justo-Henriques, S.I.; Alves Apóstolo, J.L. Multicenter randomized controlled trial of the effects of individual reminiscence therapy on cognition, depression and quality of life: Analysis of a sample of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, F.; Jahanbin, I.; Amirsadat, A.; Moghadam, M.H. Effectiveness of Life Review Therapy on Quality of Life in the Late Life at Day Care Centers of Shiraz, Iran: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2018, 6, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, C.K.Y.; Chin, K.C.W.; Zhang, Y.; Chan, E.A. Psychological outcomes of life story work for community-dwelling seniors: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2019, 14, e12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, H.Y.; Lin, L.J. A systematic review of reminiscence therapy for older adults in Taiwan. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 26, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCambridge, J.; Witton, J.; Elbourne, D.R. Systematic Review of the Hawthorne Effect: New Concepts Are Needed to Study Research Participation Effects. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristic | Intervention (n = 37) | Control (n = 37) | χ2 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (% Within Row) | n | (% Within Row) | |||

| Gender | 1.51 | N.S. | ||||

| Male | 22 | (44.9) | 27 | (55.1) | ||

| Female | 15 | (60.0) | 10 | (40.0) | ||

| Marital Status | 4.96 | N.S. | ||||

| Married | 23 | (52.3) | 21 | (47.7) | ||

| Single | 8 | (72.7) | 3 | (27.3) | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 3 | (33.3) | 6 | (66.7) | ||

| Widowed | 3 | (30.0) | 7 | (70.0) | ||

| Ethnicity | 12.92 | <0.05 | ||||

| Chinese | 13 | (31.7) | 28 | (68.3) | ||

| Malay | 13 | (76.5) | 4 | (23.5) | ||

| Indian | 10 | (66.7) | 5 | (33.3) | ||

| Others | 1 | (100) | 0 | (0) | ||

| Religious beliefs | 2.66 | N.S. | ||||

| Christianity/Catholicism | 6 | (28.6) | 15 | (71.4) | ||

| Buddhism | 8 | (40.0) | 12 | (60.0) | ||

| Taoism | 0 | (0) | 1 | (100) | ||

| Islam | 13 | (65.0) | 7 | (35.0) | ||

| Hinduism | 9 | (81.8) | 2 | (18.2) | ||

| Others | 1 | (100) | 0 | (0) | ||

| Educational level | 2.28 | N.S. | ||||

| Primary school and below | 27 | (51.9) | 25 | (48.1) | ||

| Secondary level | 9 | (45.0) | 11 | (55.0) | ||

| Tertiary level | 1 | (50.0) | 1 | (50.0) | ||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p-value | |

| GDS-15 scores (Baseline) | 8.43 | 1.04 | 8.73 | 1.24 | 1.12 | 0.268 |

| LSIA scores (Baseline) | 10.24 | 1.40 | 9.00 | 1.78 | −3.34 | <0.05 |

| QoL-NHR scores (Baseline) | 144.64 | 2.62 | 146.72 | 4.55 | 2.41 | 0.946 |

| GDS-15 Scores | Intervention (n = 37) | Control (n = 37) | DID (Sig.) |  | ||

| Mean | (S.D.) | Mean | (S.D.) | |||

| Baseline (T1) | 8.43 | 1.04 | 8.43 | 1.04 | - | |

| Week 1 (T2) | 8.16 | 1.50 | 8.49 | 1.43 | −0.027 | |

| Week 2 (T3) | 7.35 | 1.51 | 8.38 | 1.36 | −0.730 | |

| Week 4 (T4) | 5.81 | 0.91 | 8.43 | 1.34 | −2.324 * | |

| Week 8 (T5) | 4.73 | 1.17 | 8.76 | 1.36 | −3.730 * | |

| Week 12 (T6) | 4.22 | 0.95 | 8.24 | 1.04 | −3.730 * | |

| LSIA Scores | Intervention (n = 37) | Control (n = 37) | DID (Sig.) |  | ||

| Mean | (S.D.) | Mean | (S.D.) | |||

| Baseline (T1) | 10.24 | 1.40 | 9.00 | 1.78 | - | |

| Week 1 (T2) | 10.27 | 1.22 | 9.62 | 1.23 | −0.595 | |

| Week 2 (T3) | 10.30 | 1.13 | 9.70 | 1.22 | −0.649 | |

| Week 4 (T4) | 10.59 | 1.57 | 9.46 | 1.04 | −0.108 | |

| Week 8 (T5) | 11.54 | 2.60 | 9.51 | 1.24 | 0.784 | |

| Week 12 (T6) | 12.27 | 2.13 | 9.73 | 1.10 | 1.297 * | |

| QoL-NHR Scores | Intervention (n = 37) | Control (n = 37) | DID (Sig.) |  | ||

| Mean | (S.D.) | Mean | (S.D.) | |||

| Baseline (T1) | 144.64 | 2.62 | 146.72 | 4.55 | - | |

| Week 1 (T2) | 144.35 | 2.58 | 144.31 | 2.58 | 2.122 * | |

| Week 2 (T3) | 151.86 | 4.11 | 143.57 | 1.94 | 10.378 * | |

| Week 4 (T4) | 151.84 | 3.19 | 143.73 | 1.92 | 10.189 * | |

| Week 8 (T5) | 152.11 | 3.28 | 144.41 | 2.54 | 9.784 * | |

| Week 12 (T6) | 155.73 | 3.05 | 145.62 | 2.63 | 12.189 * | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guna, D.; Milburn-Curtis, C.; Zhang, H.; Goh, H.S. Effectiveness of the Biography and Life Storybook for Nursing Home Residents: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084749

Guna D, Milburn-Curtis C, Zhang H, Goh HS. Effectiveness of the Biography and Life Storybook for Nursing Home Residents: A Quasi-Experimental Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084749

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuna, Doraisamy, Coral Milburn-Curtis, Hui Zhang, and Hongli Sam Goh. 2022. "Effectiveness of the Biography and Life Storybook for Nursing Home Residents: A Quasi-Experimental Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 8: 4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084749

APA StyleGuna, D., Milburn-Curtis, C., Zhang, H., & Goh, H. S. (2022). Effectiveness of the Biography and Life Storybook for Nursing Home Residents: A Quasi-Experimental Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084749