The Adaptation and Validation of the Trans Attitudes and Beliefs Scale to the Spanish Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Social and Legal Context for Spanish Trans People

1.2. Transphobia in Psychological Sciences

1.3. The Trans Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (TABS)

1.4. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Questionnaire including Sociodemographic Aspects

2.3.2. Trans Attitude and Belief Scale (TABS)

2.3.3. Genderism and Transphobia Subscale-Revised (GTSS-R)

2.3.4. Ambivalent Sexism Inventory-Short Version (ASI)

2.3.5. Modern Homonegativity Scale (MHS)

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

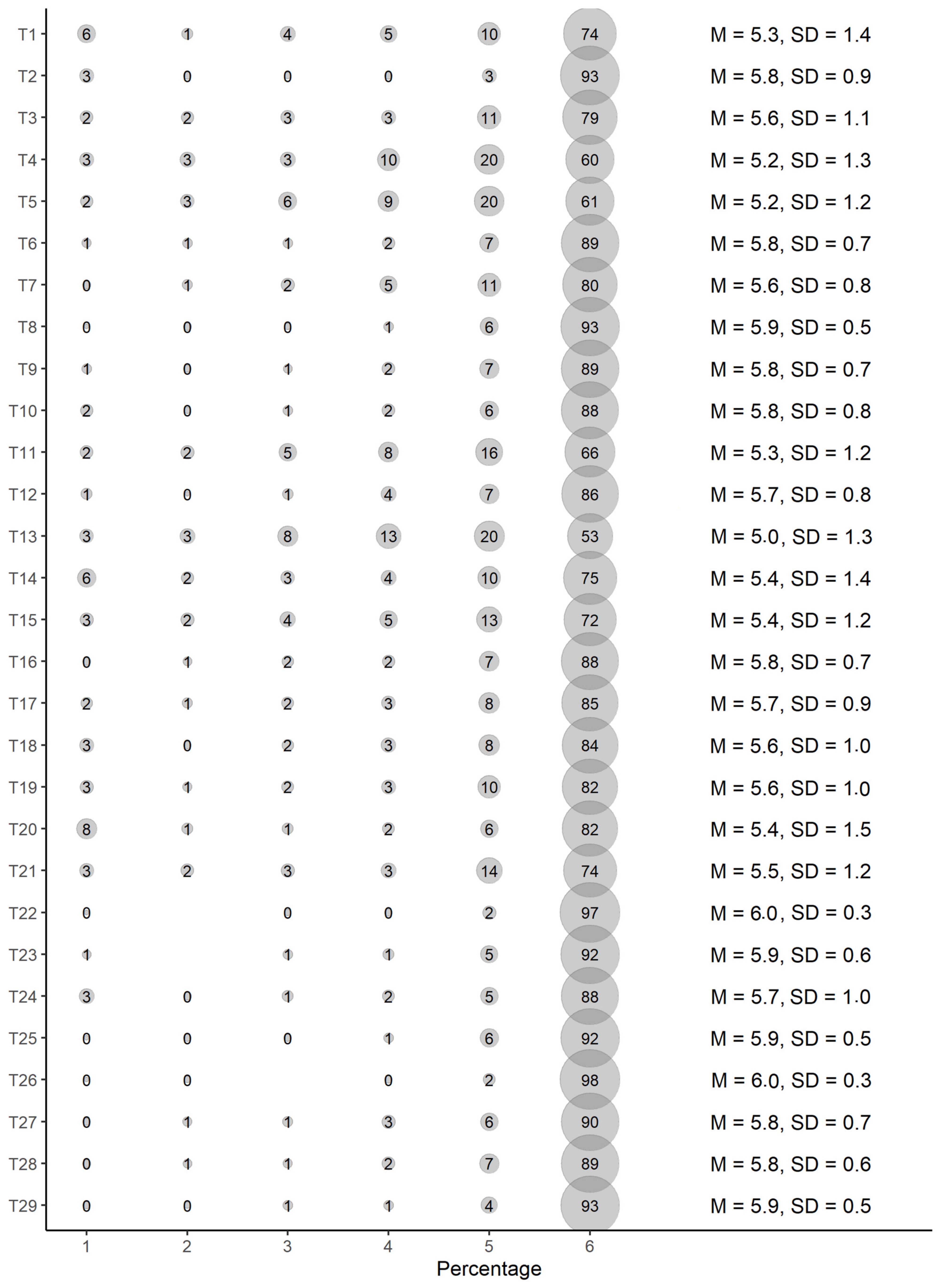

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

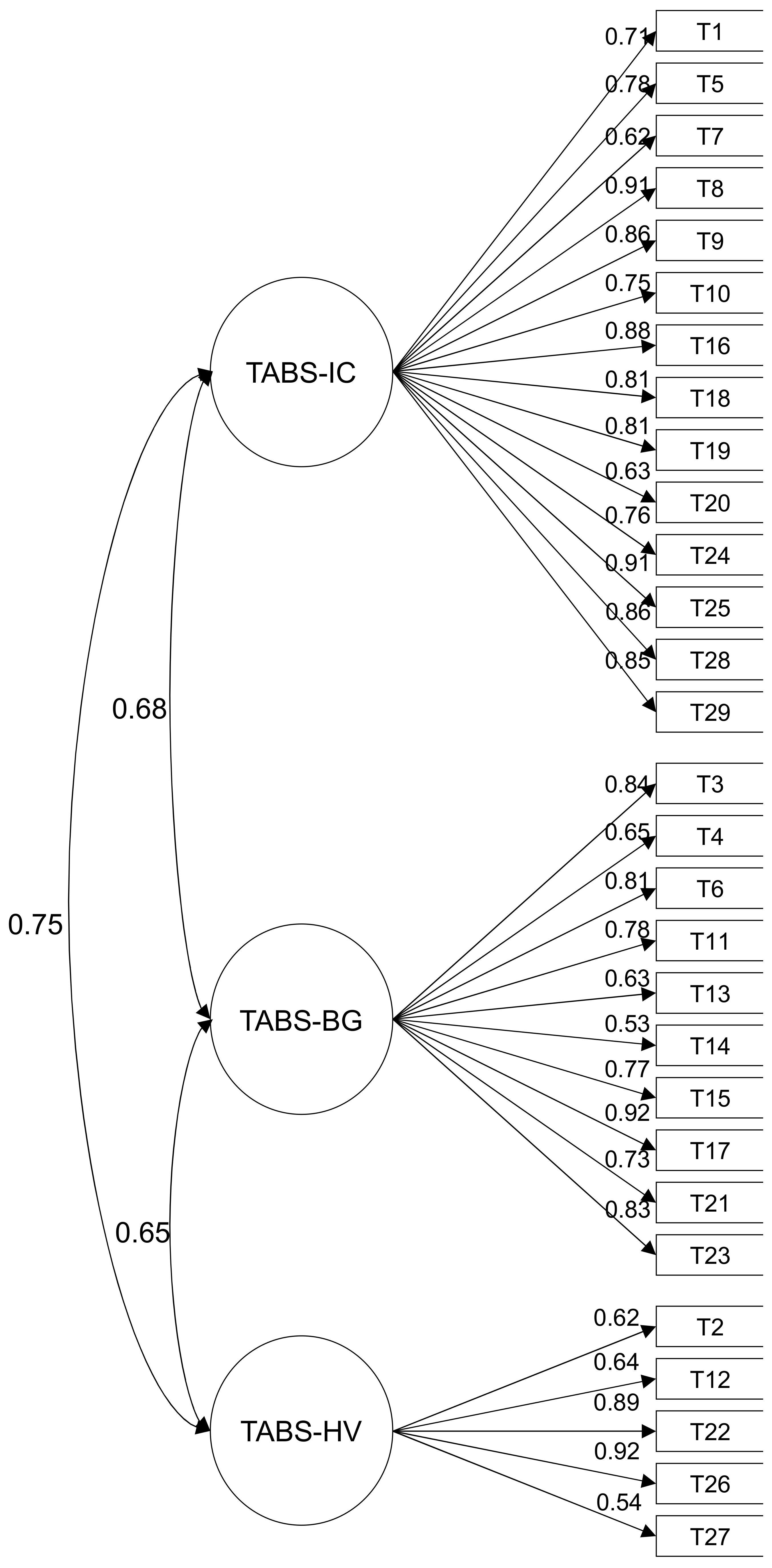

3.2. Evidence of Internal Structure

3.3. Internal Consistency of the Sum Scores

3.4. Evidence of Validity Based on the Relationship with Other Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items of the Spanish Version/Original TABS Items | Dimensions/Factors |

|---|---|

| 1. Yo sentiría comodidad si mi compa o vecino/a/e de al lado fuese trans/I would feel comfortable if my next-door neighbor was transgender | Interpersonal comfort |

| 2. Me parecería inaceptable que se molestara o maltratara a una persona trans/I would find it highly objectionable to see a transgender person being teased or mistreated. | Human value |

| 3. Si una persona es hombre o mujer depende estrictamente de sus órganos genitales externos/Whether a person is male or female depends strictly on their external sex parts (R). | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 4. Aunque la mayor parte de la humanidad son hombres o mujeres, también hay otro tipo de identidades/Although most of humanity is male or female, there are also identities in between. | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 5. Yo sentiría comodidad dentro de un grupo de personas trans/I would be comfortable being in a group of transgender individuals. | Interpersonal comfort |

| 6. Una persona que no está segura de ser hombre o mujer esta mentalmente enferma/A person who is not sure about being male or female is mentally ill (R). | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 7. Me molestaría si alguien que conozco desde hace mucho tiempo me revelara que antes había vivido con otra identidad de género/I would be upset if someone I’d known for a long time revealed that they used to be another gender (R). | Interpersonal comfort |

| 8. Si supiese que alguien es trans, tendería a evitar a esa persona/If I knew someone was transgender, I would tend to avoid that person (R) | Interpersonal comfort |

| 9. Incluso sabiendo que alguien es trans, estaría abierto a tener una amistad con esa persona/If I knew someone was transgender, I would still be open to forming a friendship with that person. | Interpersonal comfort |

| 10. Yo sentiría comodidad trabajando para una entidad que da la bienvenida a personas trans/I would be comfortable working for a company that welcomes transgender individuals. | Interpersonal comfort |

| 11. Todos los adultos tienen que identificarse como hombres o mujeres/All adults should identify as either male or female (R). | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 12. Las personas trans son seres humanos valiosos, independientemente de cómo me sienta con respecto a lo trans/Transgender individuals are valuable human beings regardless of how I feel about transgenderism. | Human value |

| 13. Un/a/e bebe nacido con órganos genitales ambiguos debería ser identificada o bien como chico o bien como chica/A child born with ambiguous sex parts should be assigned to be either male or female (R). | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 14. Una persona no tiene que ser claramente hombre o mujer para ser normal y estar sana/A person does not have to be clearly male or female to be normal and healthy. | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 15. En la humanidad sólo hay hombres o mujeres; no hay nada más/Humanity is only male or female; there is nothing in between (R). | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 16. Si una persona trans optase a ser compañera de piso, la rechazaría/If a transgender person asked to be my housemate, I would want to decline (R). | Interpersonal comfort |

| 17. Si naces hombre, nada de lo que hagas cambiará eso/If you are born male, nothing you do will change that (R). | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 18. Yo sentiría comodidad comiendo con una persona trans en mi casa/I would feel comfortable having a transgender person into my home for a meal. | Interpersonal comfort |

| 19. Si mi hijo/a/e trajese a casa a una amistad trans, sentiría comodidad al tener a esa persona en mi casa/If my child brought home a transgender friend, I would be comfortable having that person in my home. | Interpersonal comfort |

| 20. Yo sentiría incomodidad trabajando estrechamente con una persona trans en mi lugar de trabajo/I would feel uncomfortable working closely with a transgender person in my workplace (R). | Interpersonal comfort |

| 21. Si una persona es hombre o mujer depende de cómo se sienta él o ella/Whether a person is male or female depends upon whether they feel male or female. | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 22. Las personas trans deben tener el mismo acceso a la vivienda que cualquier otra persona/Transgender individuals should have the same access to housing as any other person. | Human value |

| 23. Si una persona trans se identifica como mujer (o con una mujer), debe tener derecho a casarse/If a transgender person identifies as female, she should have the right to marry a man. | Beliefs regarding gender identity |

| 24. Yo sentiría incomodidad si mi jefe/a/x fuese trans/I would be uncomfortable if my boss was transgender (R) | Interpersonal comfort |

| 25. Si alguien que conocía me revelase que es trans, probablemente me alejaría de esa persona/If someone I knew revealed to me that they were transgender, I would probably no longer be as close to that person (R). | Interpersonal comfort |

| 26. Las personas trans deben ser tratadas con el mismo respeto y dignidad que cualquier otra persona/Transgender individuals should be treated with the same respect and dignity as any other person. | Human value |

| 27. Las personas trans son seres humanos con sus propias luchas, como el resto de la gente/Transgender individuals are human beings with their own struggles, just like the rest of us. | Human value |

| 28. Yo sentiría incomodidad descubriendo que estoy solo con una persona trans/I would feel uncomfortable finding out that I was alone with a transgender person. | Interpersonal comfort |

| 29. Si la persona que me atiende en mi centro de salud fuera trans, preferiría que me atendiera otra persona/If I found out my doctor was transgender, I would want to seek another doctor (R). | Interpersonal comfort |

References

- Seccion Quinta. Sentencia de la Audiencia Provincial de Barcelona 9029/92, de 30 de junio de 1994. In Juzgado de Instrucción de Barcelona no 23; Audiencia Provincial de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1994; pp. 2–92. [Google Scholar]

- Missé, M. A la Conquista del Cuerpo Equivocado. Egales: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Platero, R.L. Redistribution and recognition in Spanish Transgender Laws. Pol. Gov. 2020, 8, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidencia, M.; Justicia, M.; Igualdad, M. Anteproyecto de Ley para la Igualdad Real y Efectiva de las Personas Trans y Para la Garantía de los Derechos de las Personas LGTBI; Presidencia: Madrid, Spain, 2021.

- ILGA-Europe. Annual Review of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Gisexual, Trans, and Intersex People, Covering Events that Occurred in Europe and Central Asia between January–December 2020; ILGA: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alabao, N. El Feminismo de las Élites Busca Recuperar la Centralidad Perdida; Cuarto Poder: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duval, E. Después de lo Trans: Sexo y Género Entre la Izquierda y lo Identitario; La Caja Books: Valencia, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, Á. Contra el Borrado de las Mujeres; Eldiario.es: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agencias. El Partido Feminista y Vox se Unen Contra la Ley Trans que Ven “Peligrosa” y Anticonstitucional; La Vanguardia: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Europapress. El Portavoz de los Obispos se Opone a la Ley Trans: “Ignora la Realidad Sexuada de las Células del Cuerpo”; Europapress: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Interior. Informe Sobre la Evolución de los Delitos de Odio; Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- Stryker, S. Transgender History; Seal Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- López-Sáez, M.Á.; García-Dauder, D. Los test de masculinidad/feminidad como tecnologías psicológicas de control de género. Athenea Digital 2020, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; García-Vega, E. Surgimiento, evolución y dificultades del diagnóstico de transexualismo. Rev. Asoc. Esp. Neuropsiquiatr. 2012, 32, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grau, J.M. Del transexualismo a la disforia de género en el DSM. Cambios terminológicos, misma esencia patologizante. Rev. Int. Soc. 2017, 75, e059-1–e059-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sáez, M.Á.; García-Dauder, D.; Montero, I. Correlate attitudes toward LGBT and sexism in Spanish psychology students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, M.A.; Bishop, C.J.; Gazzola, S.B.; McCutcheon, J.M.; Parker, K.; Morrison, T.G. Systematic review of the psychometric properties of transphobia scales. Int. J. Transgenderism 2017, 18, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, T.J. Attitudes toward Transgender Men and Women: Development and Validation of a New Measure. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.B. Genderism, transphobia, and gender bashing: A framework for interpreting anti-transgender violence. In Understanding and Dealing with Violence: A Multicultural Approach; Wallace, B., Carter, R., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, D.B.; Willoughby, B.L. The development and validation of the genderism and transphobia Scale. Sex Roles 2005, 53, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Fernández, M.V.; Lameiras-Fernández, M.; Rodríguez-Castro, Y.; Vallejo-Medina, P. Spanish adolescents’ attitudes toward transpeople: Proposal and validation of a short form of the genderism and transphobia scale. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 654–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebbe, E.A.; Moradi, B.; Ege, E. Revised and abbreviated forms of the genderism and transphobia scale: Tools for assessing anti-trans prejudice. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagoshi, J.L.; Adams, K.A.; Terrell, H.K.; Hill, E.D.; Brzuzy, S.; Nagoshi, C.T. Gender differences in correlates of homophobia and transphobia. Sex Roles 2008, 59, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, Y.; Cornelius-White, J.H.; Pegors, T.K.; Daniel, T.; Hulgus, J. Development and validation of the transgender attitudes and beliefs scale. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 1503–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CIS. Barómetro de julio 2019: Avance de resultados; Estudio no 2019, 3257; Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2019.

- López-Sáez, M.Á.; García-Dauder, D.; Montero, I.; Lecuona, Ó. Adaptation and validation of the evasive attitudes of sexual orientation scale into Spanish. J. Homosex. 2021, 69, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamori, Y.; Xu, Y.J. Factors associated with transphobia: A structural equation modeling approach. J. Homosex. 2020, 69, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, Y.; Cornelius-White, J.H. Big changes, but are they big enough? Healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward transgender persons. Int. J. Transgenderism 2016, 17, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Kucharska, J.; Marczak, M. Mental health practitioners’ attitudes towards transgender people: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Transgenderism 2018, 19, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Picaza, M.; Jiménez-Etxebarria, E.; Cornelius-White, J.H. Measuring discrimination against transgender people at the university of the Basque country and in a non-university sample in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FELGTB. Las Personas Trans y su Relación con el Sistema Sanitario; FELGTB: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, L.; Cuadrado, F. Percepción de las personas transexuales sobre la atención sanitaria. Ind. Enferm. 2020, 29, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-García, M.E.; Díaz-Ramiro, E.M.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; López-Núñez, M.I.; García-Nieto, I. Health and well-being of cisgender, transgender and non-binary young people. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergero-Miguel, T.; García-Encinas, M.A.; Villena-Jimena, A.; Pérez-Costillas, L.; Sánchez-Álvarez, N.; Diego-Otero, Y.; Guzman-Parra, J. Gender dysphoria and social anxiety: An exploratory study in Spain. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Parra, J.; Sánchez-Álvarez, N.; de Diego-Otero, Y.; Pérez-Costillas, L.; De Antonio, I.E.; Navais-Barranco, M.; Castro-Zamudio, S.; Bergero-Miguel, T. Sociodemographic characteristics and psychological adjustment among transsexuals in Spain. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANECA. Libro Blanco: Estudios de Grado en Psicología; ANECA: Madrid, Spain, 2005.

- Billard, T.J. The crisis in content validity among existing measures of transphobia. Arch. Sex Beha. 2018, 47, 1305–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbner, G.; Gross, L.; Morgan, M.; Signorielli, N. Political correlates of television viewing. Public Opin. Q. 1984, 48, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollero, C.; Glick, P.; Tartaglia, S. Psychometric properties of short versions of the ambivalent sexism inventory and ambivalence toward men inventory. Testing Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 21, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, M.A.; Morrison, T.G. Development and validation of a scale measuring modern prejudice toward gay men and lesbian women. J. Homosex. 2003, 43, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viladrich, C.; Angulo-Brunet, A.; Doval, E. A trip around alpha and omega to estimate internal consistency reliability. Ann. Psychol. 2017, 33, 755–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R Package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.B.; Yang, Y. Reliability of summed item scores using structural equation modeling: An alternative to coefficient alpha. Psychometrika 2009, 74, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori, Y.; Pegors, T.K.; Hulgus, J.F.; Cornelius-White, J.H.D. A comparison between self-identified evangelical christians’ and nonreligious persons’ attitudes toward transgender persons. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2017, 4, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierckx, M.; Meier, P.; Motmans, J. Beyond the box: A comprehensive study of sexist, homophobic, and transphobic attitudes among the Belgian population. Digest. J. Divers. Gend. Stud. 2017, 4, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, B.J.; Merritt, O.A.; Straatsma, D. Individual difference predictors of transgender beliefs: Expanding our conceptualization of conservatism. Personal. Ind. Difference 2019, 149, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warriner, K.; Nagoshi, C.T.; Nagoshi, J.L. Correlates of homophobia, transphobia, and internalized homophobia in gay or lesbian and heterosexual samples. J. Homosexual. 2013, 60, 1297–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisley, M. Counseling Professionals’ Attitudes toward Transgender People and Responses to Transgender Clients. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 2010. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori, Y.; Cornelius-White, J.H. Counselors’ and counseling students’ attitudes toward transgender persons. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 2017, 11, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes-Ribera, L.; Frias-Navarro, D.; Monterde-i-Bort, H.; Pascual-Soler, M. Spanish validation of the polymorphous prejudice scale in a sample of university students. J. Homosexual. 2016, 63, 1517–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sáez, M.Á.; García-Dauder, D.; Montero, I.; Lecuona, Ó. Adaptation and validation of the LGBQ ally identity measure (Adaptación y validación de la Medida de Identificación Aliada LGBQ). Estud. Psicol. 2021, 43, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlin, S.E.; Douglass, R.P.; Moscardini, E.H. Predicting transphobia among cisgender women and men: The roles of feminist identification and gender conformity. J. Gay Lesbian Mental Health 2021, 25, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.; Stoller, R.J.; MacAndrew, C. Attitudes toward sex transformation procedures. Arch. General Psychiatry 1966, 15, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzini, L.R.; Casinelli, D.L. Health professionals’ factual knowledge and changing attitudes toward transsexuals. Soc. Sci. Med. 1986, 22, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Cuerpos que Importan: Sobre los Límites Materiales y Discursivos del Sexo; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Undoing Gender; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. Vivir una Vida Feminista; Edicions Bellaterra: Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. Fenomenología Queer: Orientaciones, Objetos, Otros; Edicions Bellaterra: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FRA. A Long Way to Go for LGBTI Equality; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.E. The Impact of Microaggressions in Therapy on Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Clients: A Concurrent Nested Design Study; University of the Rockies: Denver, CO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, L.M.; Budge, S.L. Suicide and the transgender experience: A public health crisis. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebbe, E.A.; Moradi, B. Suicide risk in trans populations: An application of minority stress theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 63, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.E.; Herman, J.L.; Rankin, S.; Keisling, M.; Mottet, L.; Anafi, M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey; National Center for Transgender Equality: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mikalson, P.; Pardo, S.; Green, J. First Do No Harm: Reducing Disparities for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Questioning Populations in California: The California LGBTQ Reducing Mental Health Disparities Population Report; California Department of Public Health: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks, M.L.; Testa, R.J. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An Adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2012, 43, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heterosexuals | LGB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Trans comfort (TABS-IC) | 5.37 | 0.81 | 5.68 | 0.47 | 5.69 | 0.50 | 5.86 | 0.22 |

| Trans beliefs (TABS-BG) | 5.14 | 0.95 | 5.48 | 0.72 | 5.54 | 0.65 | 5.63 | 0.46 |

| Trans value (TABS-HV) | 5.81 | 0.37 | 5.86 | 0.34 | 5.76 | 0.54 | 5.90 | 0.24 |

| Transphobia (GTSS-R) | 5.47 | 0.75 | 5.76 | 0.40 | 5.74 | 0.49 | 5.91 | 0.16 |

| Hostile sexism (ASI-HS) | 2.15 | 0.99 | 1.53 | 0.63 | 1.39 | 0.54 | 1.30 | 0.50 |

| Benevolent sexism (ASI-BS) | 2.26 | 0.98 | 1.98 | 0.70 | 1.99 | 0.71 | 1.76 | 0.60 |

| Lesbian negativity (MHS-L) | 2.35 | 1.06 | 1.86 | 0.77 | 1.49 | 0.64 | 1.33 | 0.42 |

| Gay negativity (MHS-G) | 2.40 | 1.02 | 1.95 | 0.76 | 1.55 | 0.58 | 1.42 | 0.41 |

| Political affiliation | 2.04 | 0.87 | 1.96 | 0.83 | 1.42 | 0.63 | 1.42 | 0.65 |

| Religiousness | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.34 |

| No LG contact | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| No B contact | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 014 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| No T contact | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.20 | 0.40 |

| Variable | M | SD | Mdn | Sk | k | ω | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TABS-IC | 5.67 | 0.52 | 83 | −2.8 | 11.4 | 0.67 | 0.83 |

| TABS-BG | 5.47 | 0.73 | 57 | −2.5 | 7.8 | 0.80 | 0.86 |

| TABS-HV | 5.85 | 0.35 | 30 | −3.1 | 11.7 | 0.30 | 0.38 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TABS dimensions | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. TABS-IC | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 2. TABS-BG | 0.50 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 3. TABS-HV | 0.38 *** | 0.27 *** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Theoretically related scales | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. GTS-R | 0.72 *** | 0.74 *** | 0.33 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 5. ASI-HS | −0.40 *** | −0.39 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.49 *** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 6. ASI-BS | −0.35 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.38 *** | 0.46 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 7. MHS-L | −0.51 *** | −0.58 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.65 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.42 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| 8. MHS-G | −0.51 *** | −0.58 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.64 *** | 0.65 *** | 0.4 *** | 0.95 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||||||||||||||

| 9. PA | −0.33 *** | −0.30 *** | −0.14 *** | −0.36 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.52 *** | 1 | |||||||

| 10. REL | −0.20 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.07 * | −0.24 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.44 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 11. LLGC | −0.16 *** | −0.11 *** | −0.07 * | −0.16 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.06 | 0.16 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1 | |||||

| 12. LBC | −0.21 *** | −0.10 *** | −0.06 | −0.15 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.2 *** | 0.2 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.07 | 0.25 *** | 1 | ||||

| 13. LTC | −0.10 ** | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.07 * | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.17 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.11 ** | 0.02 | 0.22 *** | 0.36 *** | 1 | |||

| 14. AY | 0.02 | 0.07 * | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.09 * | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1 | ||

| 15. GI | 0.20 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.09 * | 0.22 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.14 *** | −0.17 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.02 | 0.07 * | −0.09 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.01 | 0.00 | 1 | |

| 16. SO | 0.18 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.02 | 0.16 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.14 *** | −0.33 *** | −0.33 *** | −0.3 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.05 | −0.11 ** | −0.11 *** | −0.09 * | −0.03 | 1 |

| B | CI95% | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Il | Ul | ||||

| DV: Trans comfort (TABS-IC) | |||||

| Intercept | 6.46 | 6.34 | 6.56 | 129.55 | <0.001 |

| Hostile sexism (ASI-HS) | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.02 | −1.22 | 0.23 |

| Benevolent sexism (ASI-BS) | −0.10 | −0.15 | −0.05 | −4.27 | <0.001 *** |

| Modern homonegativity (MHS) | −0.26 | −0.31 | −0.21 | −9.68 | <0.001 *** |

| Political affiliation (PA) | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.01 | −1.43 | 0.15 |

| DV: Trans beliefs (TABS-BG) | |||||

| Intercept | 6.45 | 6.34 | 6.57 | 11.27 | <0.001 |

| Hostile sexism (ASI-HS) | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.07 | −0.23 | 0.82 |

| Modern homonegativity (MHS) | −0.54 | −0.61 | −0.46 | −14.90 | <0.001 *** |

| Political affiliation (PA) | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.81 |

| DV: Trans human values (TABS-HV) | |||||

| Intercept | 6.11 | 6.05 | 6.19 | 166.89 | >0.001 |

| Hostile sexism (ASI-HS) | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.82 | 0.41 |

| Benevolent sexism (ASI-BS) | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.00 | −2.15 | 0.03 * |

| Modern homonegativity (MHS) | −0.08 | −0.12 | −0.05 | −4.35 | >0.001 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Sáez, M.Á.; Angulo-Brunet, A.; Platero, R.L.; Lecuona, O. The Adaptation and Validation of the Trans Attitudes and Beliefs Scale to the Spanish Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074374

López-Sáez MÁ, Angulo-Brunet A, Platero RL, Lecuona O. The Adaptation and Validation of the Trans Attitudes and Beliefs Scale to the Spanish Context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074374

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Sáez, Miguel Ángel, Ariadna Angulo-Brunet, R. Lucas Platero, and Oscar Lecuona. 2022. "The Adaptation and Validation of the Trans Attitudes and Beliefs Scale to the Spanish Context" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074374

APA StyleLópez-Sáez, M. Á., Angulo-Brunet, A., Platero, R. L., & Lecuona, O. (2022). The Adaptation and Validation of the Trans Attitudes and Beliefs Scale to the Spanish Context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074374