The Relationship of Shopping-Related Decisions with Materialistic Values Endorsement, Compulsive Buying-Shopping Disorder Symptoms and Everyday Moral Decision Making

Abstract

:1. Introduction

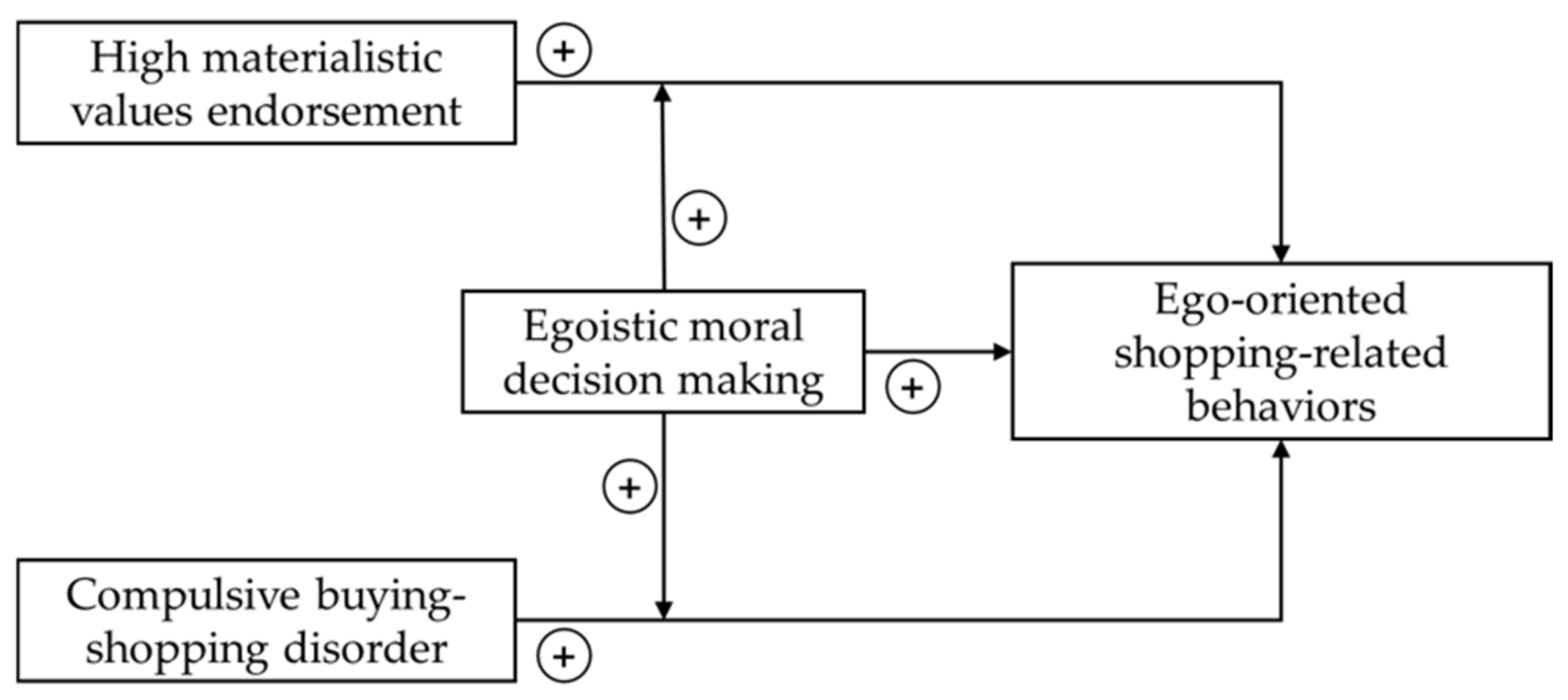

1.1. Aims

1.2. Hypotheses

- Higher material values endorsement is related to more ego-oriented shopping-related decisions.

- More symptoms of CBSD are related to more ego-oriented shopping-related decisions.

- A more egoistic everyday moral decision making style is related to more ego-oriented shopping-related decisions.

- A more egoistic everyday moral decision making style strengthens the association between materialistic values endorsement/symptoms of CBSD and ego-oriented shopping-related decisions.

2. Study 1: Development of Shopping-Related Dilemmas

2.1. Material and Methods

2.1.1. Procedure

2.1.2. Instruments

2.1.3. Participants with CBSD

2.2. Results

3. Study 2: Online Survey

3.1. Material and Methods

3.1.1. Procedure

3.1.2. Instruments

3.1.3. Participants

3.1.4. Statistical Analyses

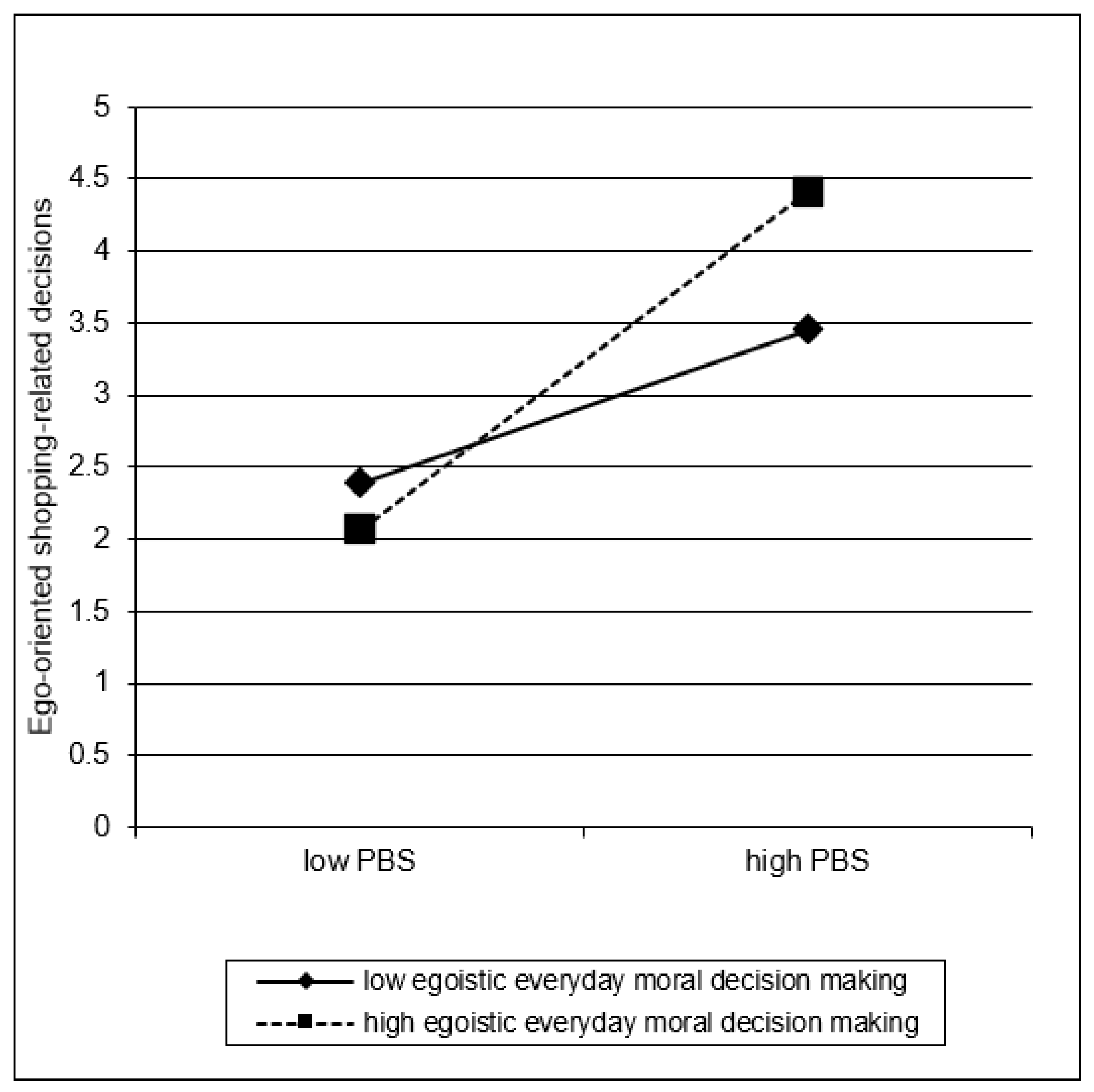

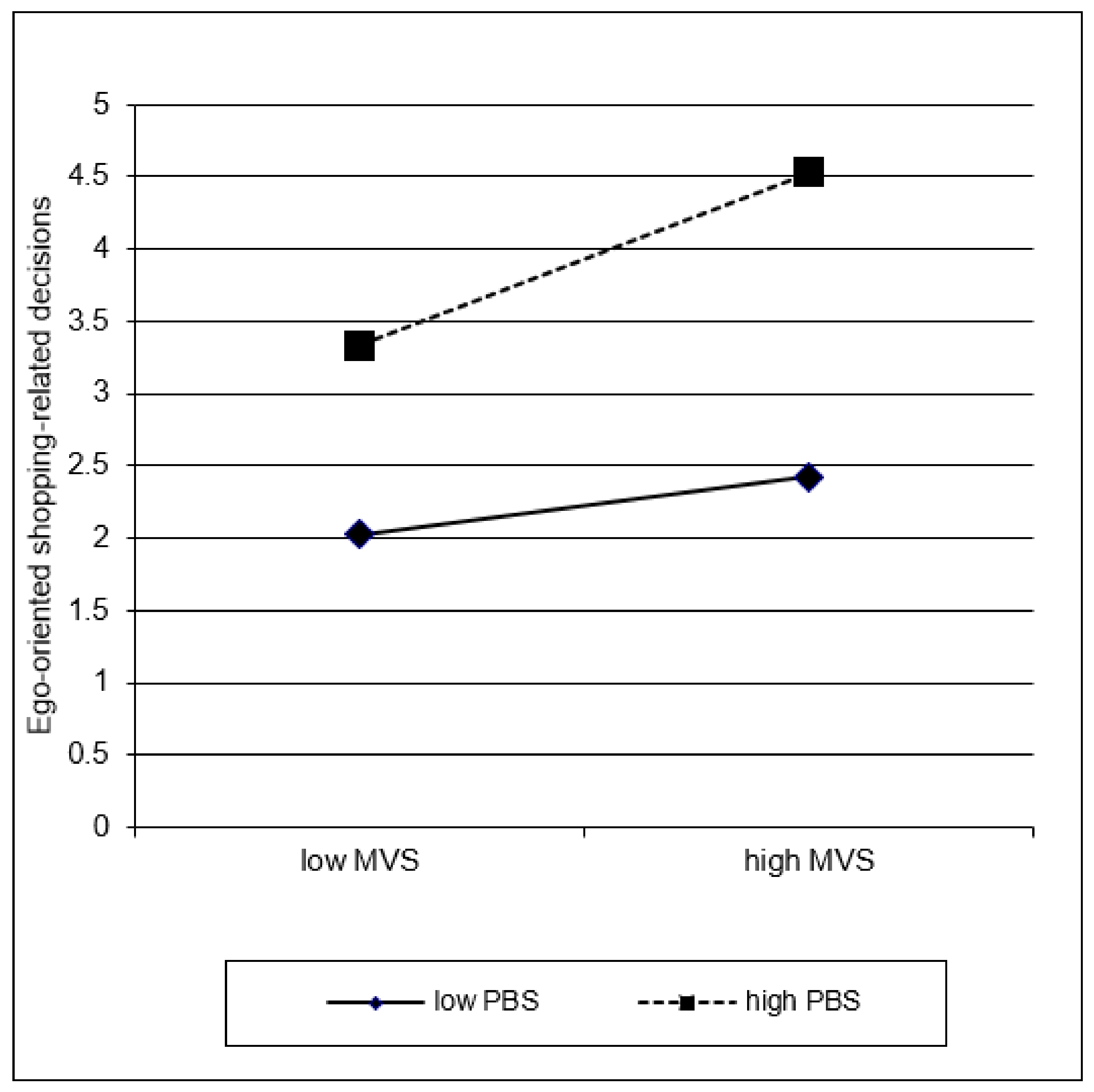

3.2. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Granero, R.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Bano, M.; Del Pino-Gutierrez, A.; Moragas, L.; Mallorqui-Bague, N.; Aymami, N.; Gomez-Pena, M.; et al. Compulsive buying behavior: Clinical comparison with other behavioral addictions. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.; Laskowski, N.M.; Trotzke, P.; Ali, K.; Fassnacht, D.; de Zwaan, M.; Brand, M.; Häder, M.; Kyrios, M. Proposed diagnostic criteria for compulsive buying-shopping disorder: A Delphi expert consensus study. J. Behav. Addict. 2021, 10, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maraz, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Demetrovics, Z. The prevalence of compulsive buying: A meta-analysis. Addiction 2016, 111, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. Available online: https://icd.who.int/en/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Brand, M.; Rumpf, H.J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Müller, A.; Stark, R.; King, D.L.; Goudriaan, A.E.; Mann, K.; Trotzke, P.; Fineberg, N.A.; et al. Which conditions should be considered as disorders in the Internationl Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) designation of “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors”? J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 1–10, Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrios, M.; Trotzke, P.; Lawrence, L.; Fassnacht, D.B.; Ali, K.; Laskowski, N.M.; Müller, A. Behavioral neuroscience of buying-shopping disorder: A review. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 5, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Brand, M.; Claes, L.; Demetrovics, Z.; de Zwaan, M.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Frost, R.O.; Jimenez-Murcia, S.; Lejoyeux, M.; Steins-Loeber, S.; et al. Buying-shopping disorder-is there enough evidence to support its inclusion in ICD-11? CNS Spectr. 2019, 24, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achtziger, A.; Hubert, M.; Kenning, P.; Raab, G.; Reisch, L.A. Debt out of control: The links between self-control, compulsive buying, and real debts. J. Econ. Psychol. 2015, 49, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christenson, G.A.; Faber, R.J.; de Zwaan, M.; Raymond, N.C.; Specker, S.M.; Ekern, M.D.; Mackenzie, T.B.; Crosby, R.D.; Crow, S.J.; Eckert, E.D.; et al. Compulsive buying: Descriptive characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 55, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Croissant, B.; Klein, O.; Löber, S.; Mann, K. Ein Fall von Kaufsucht—Impulskontrollstörung oder Abhängigkeitserkrankung? [A case of compulsive buying--impulse control disorder or dependence disorder?]. Psychiatr. Prax. 2009, 36, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, V.; Laskowski, N.M.; de Zwaan, M.; Müller, A. Kaufen bis zum Umfallen—Ein Fallbereicht [Shop ‘til you drop—A case report]. Verhalt. Verhalt. 2019, 40, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, M.; Wegmann, E.; Stark, R.; Müller, A.; Wölfling, K.; Robbins, T.W.; Potenza, M.N. The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 104, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everitt, B.J.; Robbins, T.W. Drug addiction: Updating actions to habits to compulsions ten years on. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.A.; Jones, E. Money attitudes, credit card use, and compulsive buying among American college students. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.A.; Chang, J.; Jewell, B.; Sellbom, M. Relationships among shoplifting, compulsive buying, and borderline personality symptomatology. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 8, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Adolphe, A.; Khatib, L.; van Golde, C.; Gainsbury, S.M.; Blaszczynski, A. Crime and gambling disorders: A systematic review. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019, 35, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero, R.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Aymami, N.; Gomez-Pena, M.; Fagundo, A.B.; Sauchelli, S.; Del Pino-Gutierrez, A.; Moragas, L.; Savvidou, L.G.; Islam, M.A.; et al. Subtypes of pathological gambling with concurrent illegal behaviors. J. Gambl. Stud. 2015, 31, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dootson, P.; Johnston, K.A.; Beatson, A.; Lings, I. Where do consumers draw the line? Factors informing perceptions and justifications of deviant consumer behaviour. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belk, R.W. Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L. The Material Values Scale: Measurement properties and development of a short form. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Pol, E.V.; Bolaño, C.C.; Mariño, M.J.S. Materialism, life-satisfaction and addictive buying: Examining the causal relationships. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, L.; Müller, A.; Luyckx, K. Compulsive buying and hoarding as identity substitutes: The role of materialistic value endorsement and depression. Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 68, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittmar, H. A new look at “compulsive buying”: Self–discrepancies and materialistic values as predictors of compulsive buying tendency. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 24, 832–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Claes, L.; Georgiadou, E.; Möllenkamp, M.; Voth, E.M.; Faber, R.J.; Mitchell, J.E.; de Zwaan, M. Is compulsive buying related to materialism, depression or temperament? Findings from a sample of treatment-seeking patients with compulsive buying. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 216, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villardefrancos, E.; Otero-Lopez, J.M. Compulsive buying in university students: Its prevalence and relationships with materialism, psychological distress symptoms, and subjective well-being. Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 65, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Lopez, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E. Materialism and addictive buying in women: The mediating role of anxiety and depression. Psychol. Rep. 2013, 113, 1342–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulding, R.; Duong, A.; Nedeljkovic, M.; Kyrios, M. Do you think that money can buy happiness? A review of the role of mood, materialism, self, and cognitions in compulsive buying. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2017, 4, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarka, P. Influence of materialism on compulsive buying behavior: General similarities and differences related to studies on young adult consumers in Poland and US. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020, 32, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, G.; Ksendzova, M.; Howell, R.T. Sadness, identity, and plastic in over-shopping: The interplay of materialism, poor credit management, and emotional buying motives in predicting compulsive buying. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L.; Dawson, S. A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T. Materialistic values and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 489–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, L.C.; Lu, C.J. Moral philosophy, materialism, and consumer ethics: An exploratory study in Indonesia. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.F.; Gomila, A. Moral dilemmas in cognitive neuroscience of moral decision-making: A principled review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 1249–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, A.L.; Raine, A.; Schug, R.A. The neural correlates of moral decision-making in psychopathy. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zijlmans, J.; Marhe, R.; Bevaart, F.; Luijks, M.A.; van Duin, L.; Tiemeier, H.; Popma, A. Neural correlates of moral evaluation and psychopathic traits in male multi-problem young adults. Front Psychiatry 2018, 9, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driessen, J.M.A.; van Baar, J.M.; Sanfey, A.G.; Glennon, J.C.; Brazil, I.A. Moral strategies and psychopathic traits. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2021, 130, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D.; Glozer, S.; Spence, L. Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann, J. Looking at consumer behavior in a moral perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 51, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.F.; Flexas, A.; Calabrese, M.; Gut, N.K.; Gomila, A. Moral judgment reloaded: A moral dilemma validation study. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Starcke, K.; Polzer, C.; Wolf, O.T.; Brand, M. Does stress alter everyday moral decision-making? Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Trotzke, P.; Mitchell, J.E.; de Zwaan, M.; Brand, M. The Pathological Buying Screener: Development and psychometric properties of a new screening instrument for the assessment of pathological buying symptoms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Trotzke, P.; Laskowski, N.M.; Brederecke, J.; Georgiadou, E.; Tahmassebi, N.; Hillemacher, T.; de Zwaan, M.; Brand, M. [The Pathological Buying Screener: Validation in a Clinical Sample]. Psychother. Psychosom Med. Psychol. 2021, 71, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.; Claes, L.; Birlin, A.; Georgiadou, E.; Laskowski, N.M.; Steins-Loeber, S.; Brand, M.; de Zwaan, M. Associations of buying-shopping disorder symptoms with identity confusion, materialism, and socially undesirable personality features in a community sample. Eur. Addict. Res. 2021, 27, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, J.B.; Brand, M.; Polzer, C.; Ebersbach, G.; Kalbe, E. Moral decision-making and theory of mind in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychology 2013, 27, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, J.B.; Rott, E.; Ebersbach, G.; Kalbe, E. Altered moral decision-making in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.; Smits, D.J.M.; Claes, L.; Gefeller, O.; Hinz, A.; de Zwaan, M. The German version of the Material Values Scale. GMS Psycho-Soc.-Med. 2013, 10, Doc05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R. Multiple Regressions: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Richins, M.L. Materialism, transformation expectations, and spending: Implications for credit use. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benson, A.L.; Eisenach, D.; Abrams, L.; van Stolk-Cooke, K. Stopping overshopping: A preliminary randomized controlled trial of group therapy for compulsive buying disorder. J. Groups Addict. Recovery 2014, 9, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, S.; Bolton, J.V. Compulsive buying: A cognitive-behavioural model. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2009, 16, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hague, B.; Hall, J.; Kellett, S. Treatments for compulsive buying: A systematic review of the quality, effectiveness and progression of the outcome evidence. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Granero, R.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Steward, T.; Bano, M.; Aguera, Z.; Mallorqui-Bague, N.; Aymami, N.; Gomez-Pena, M.; Sancho, M.; et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for compulsive buying behavior: Predictors of treatment outcome. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 39, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Arikian, A.; de Zwaan, M.; Mitchell, J.E. Cognitive-behavioural group therapy versus guided self-help for compulsive buying disorder: A preliminary study. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2013, 20, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, A.; Mueller, U.; Silbermann, A.; Reinecker, H.; Bleich, S.; Mitchell, J.E.; de Zwaan, M. A randomized, controlled trial of group cognitive-behavioral therapy for compulsive buying disorder: Posttreatment and 6-month follow-up results. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, N.; Kreuzpointner, L.; Sommer, M.; Wust, S.; Kudielka, B.M. Decision-making in everyday moral conflict situations: Development and validation of a new measure. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuner, M.; Raab, G.; Reisch, L.A. Compulsive buying in maturing consumer societies: An empirical re-inquiry. J. Econ. Psychol. 2005, 26, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-López, J.M.; Villardefrancos, E. Prevalence, sociodemographic factors, psychological distress, and coping strategies related to compulsive buying: A cross sectional study in Galicia, Spain. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otero-Lopez, J.M.; Santiago, M.J.; Castro, M.C. Big five personality traits, coping strategies and compulsive buying in Spanish university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, M.L.; Stoneback, J.Y. The importance of gender across cultures in ethical decision-making. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, M.; O’Connell, L.; Shepard, J.M. Gender differences in proclivity for unethical behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 1989, 8, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, M.; Ferrucci, R.; Mameli, F.; Marceglia, S.; Mrakic-Sposta, S.; Zago, S.; Lucchiari, C.; Consonni, D.; Nordio, F.; Pravettoni, G.; et al. Gender-related differences in moral judgments. Cogn. Process. 2010, 11, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, V.; Sippel, J. Gender differences in moral judgment and the evaluation of gender-specified moral agents. Cogn. Process. 2017, 18, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Answer | Dilemma | |

|---|---|---|

| Norm-related answer = no Ego-related answer = yes | 1 | It is the middle of the month and the money in your bank account to pay all necessary expenses will presumably just last until the end of the month. Only then will you receive the next payment (e.g., salary, student loan, pension, unemployment benefits, support from relatives, etc.). You would like to treat yourself and buy something nice. However, by buying something you would probably overdraw your bank account. Do you buy something nice for yourself? |

| 2 | You would like to order an item, but you currently do not have enough money. Would you order the item in the name of another person instead? | |

| 3 | You come across an item you would really like to have. Only yesterday you were paid money with which you can finally pay back the amount of money you are owing to a family member. Would you use the money to buy the item instead of paying the money back you are owing? | |

| 4 | You are visiting a shop and a sales assistant offers detailed advice. You originally had no intention of buying anything, but feel obliged to do so due to the service you have received. Do you buy something? | |

| 5 | You would like to buy something online. However, you still have outstanding invoices at this online retailer which prevents you to order from there. Do you place your order under another person’s name? | |

| 6 | You are currently short on cash and have recently returned an item you had ordered. So far, the refund has not been credited to your account. You see another item you would like to have. Do you buy that item? | |

| 7 | Only yesterday you were paid money to settle an outstanding invoice for medication. Now you discover an article you would like to have and consider whether you should buy the article with that money. Do you buy the item? | |

| 8 | You know that some repairs are due in your household soon, e.g., for your washing machine or your car, and you have put money aside. You see an item you would like to have. Do you buy the item? | |

| 9 | You have a guilty conscience because you have spent too much money lately. Do you still go shopping? | |

| 10 | You are annoyed with a person who is close to you. You know that he or she dislikes it when you spend money on things that are not absolutely necessary. Do you now buy something nice for yourself? | |

| 11 | You have discovered an item you would like to have which is currently on sale. You do not want to miss out the opportunity, but you do not have the money for it in the foreseeable future. Do you ask a friend or family member for the money to buy the item? | |

| 12 | You have bought an item that you would like to use. However, your relatives or people from your circle of friends have often criticised your buying behaviour, which has already led to arguments. Do you hide the item from the others? | |

| 13 | You divide your money into a weekly allowance, have set a weekly shopping list and a weekly budget. You see an item that you did not plan to purchase, but still would like to have. Do you buy the item with money from your weekly budget? | |

| 14 | You are very short on cash at the moment. You have had a bad day and you know that a stroll through the shops usually improves your mood. However, you also know that then the temptation to actually buy something is quite high. Do you go on a shopping spree? | |

| 15 | You often order goods and have them delivered to your house. You share your house with your relatives who wonder about all of those packages. You do not know how to react to the queries and are ashamed of your buying behaviour. Do you tell your relatives that you did not order the goods for yourself but for another person who has already given you the money for them? | |

| 16 | You have had unpaid accounts in recent times because you have made too many purchases. In order to settle these invoices you would like to ask a family member, who helped you out financially previously, to lend you the funds. However you are worried this person will not give you the money, once he/she finds out what it is for. Will you ask this person for the money under the pretext it is for something else? | |

| 17 | You are currently in a difficult financial situation due to private and family related problems. You would really like to treat yourself by buying something nice. You see an item on display, which you really like and would like to have. Currently you do not have the funds. Will you take the item, without paying for it? | |

| Norm-related answer = yes Ego-related answer = no | 18 | You are looking at an item that you would like to buy because you like it a lot. At the same time, you are aware that it would be good to save the money for an activity, e.g., going to the theatre, the cinema or the gym. Do you save the money for an activity? |

| 19 | You like to give big and expensive gifts. You have incurred debts through your increased spending. You are invited to a birthday party. Do you spend less on the birthday present this time than usual? | |

| 20 | You enjoy shopping for your family and yourself. You pay with the money from the joint account with your partner. Due to your spending habits you have incurred debts which your partner does not know. Do you tell him or her about the debts? | |

| 21 | You have ordered some items in the name of a family member, but cannot pay the bill. You fear that this family member might soon receive a reminder monition. Do you tell him or her that you have ordered the items on the internet in his or her name? | |

| 22 | You have ordered items online which you have received now. You do not really like them. Are you going to return the items? |

| M (SE) 95% CI | Material Values Scale | Pathological Buying Screener | Egoistic Everyday Moral Decisions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ego-oriented shopping-related decisions | 3.19 (0.14) [2.92, 3.46] | 0.35 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.09 |

| Material Values Scale | 25.42 (0.43) [24.58, 26.27] | - | 0.36 *** | 0.18 ** |

| Pathological Buying Screener | 22.13 (0.42) [21.31, 22.96] | - | - | 0.05 |

| Egoistic everyday moral decisions | 9.66 (0.15) [9.36, 9.97] | - | - | - |

| B | SE | 95% CI | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor/moderator variables | ||||||

| MVS | 0.06 | 0.02 | [0.02, 0.09] | 0.18 | 3.16 | 0.002 |

| PBS | 0.12 | 0.02 | [0.08, 0.16] | 0.38 | 6.13 | <0.001 |

| Egoistic everyday moral DM | 0.06 | 0.05 | [−0.03, 0.16] | 0.07 | 1.28 | 0.200 |

| 2-way interactions | ||||||

| MVS × PBS | 0.00 | 0.00 | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.12 | 2.09 | 0.038 |

| MVS × egoistic everyday moral DM | 0.01 | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.02] | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.325 |

| PBS × egoistic everyday moral DM | 0.02 | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.03] | 0.15 | 2.14 | 0.033 |

| 3-way interactions | ||||||

| MVS × PBS × egoistic everyday moral DM | 0.00 | 0.00 | [−0.00, 0.00] | −0.07 | −1.03 | 0.302 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Müller, A.; Georgiadou, E.; Birlin, A.; Laskowski, N.M.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Hillemacher, T.; de Zwaan, M.; Brand, M.; Steins-Loeber, S. The Relationship of Shopping-Related Decisions with Materialistic Values Endorsement, Compulsive Buying-Shopping Disorder Symptoms and Everyday Moral Decision Making. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074376

Müller A, Georgiadou E, Birlin A, Laskowski NM, Jiménez-Murcia S, Fernández-Aranda F, Hillemacher T, de Zwaan M, Brand M, Steins-Loeber S. The Relationship of Shopping-Related Decisions with Materialistic Values Endorsement, Compulsive Buying-Shopping Disorder Symptoms and Everyday Moral Decision Making. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074376

Chicago/Turabian StyleMüller, Astrid, Ekaterini Georgiadou, Annika Birlin, Nora M. Laskowski, Susana Jiménez-Murcia, Fernando Fernández-Aranda, Thomas Hillemacher, Martina de Zwaan, Matthias Brand, and Sabine Steins-Loeber. 2022. "The Relationship of Shopping-Related Decisions with Materialistic Values Endorsement, Compulsive Buying-Shopping Disorder Symptoms and Everyday Moral Decision Making" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074376

APA StyleMüller, A., Georgiadou, E., Birlin, A., Laskowski, N. M., Jiménez-Murcia, S., Fernández-Aranda, F., Hillemacher, T., de Zwaan, M., Brand, M., & Steins-Loeber, S. (2022). The Relationship of Shopping-Related Decisions with Materialistic Values Endorsement, Compulsive Buying-Shopping Disorder Symptoms and Everyday Moral Decision Making. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4376. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074376