Shyness and School Engagement in Chinese Suburban Preschoolers: A Moderated Mediation Model of Teacher–Child Closeness and Child Gender

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Indicators of (Pre-)School Engagement

1.2. Shyness and (Pre-)School Engagement

1.3. The Mediating Role of Teacher–Child Closeness

1.4. The Moderating Role of Gender

1.5. The Role of Social–Cultural Context

1.6. The Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Shyness

2.2.2. Teacher–Child Closeness

2.2.3. School Engagement

2.3. Procedure

- At T1, we collected the demographic information of children and their parents. Mothers rated their children’s shyness with CSPS. A total of 540 preschoolers from 45 classes of 15 suburban kindergartens participated in T1.

- At T2, the 45 homeroom teachers (age range: 19–44 years) of those 45 participating classes in T1 rated four indicators of school engagement for each participating child in their classes with TRSSA and SLAQ, then evaluated their closeness with each child with STRS. Their work experience in kindergarten ranged from 1.5 to 14 years. Eight preschoolers of T1 were lost due to a change in school or family residence, resulting in a final sample of 532 preschoolers.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Testing for Direct Effects

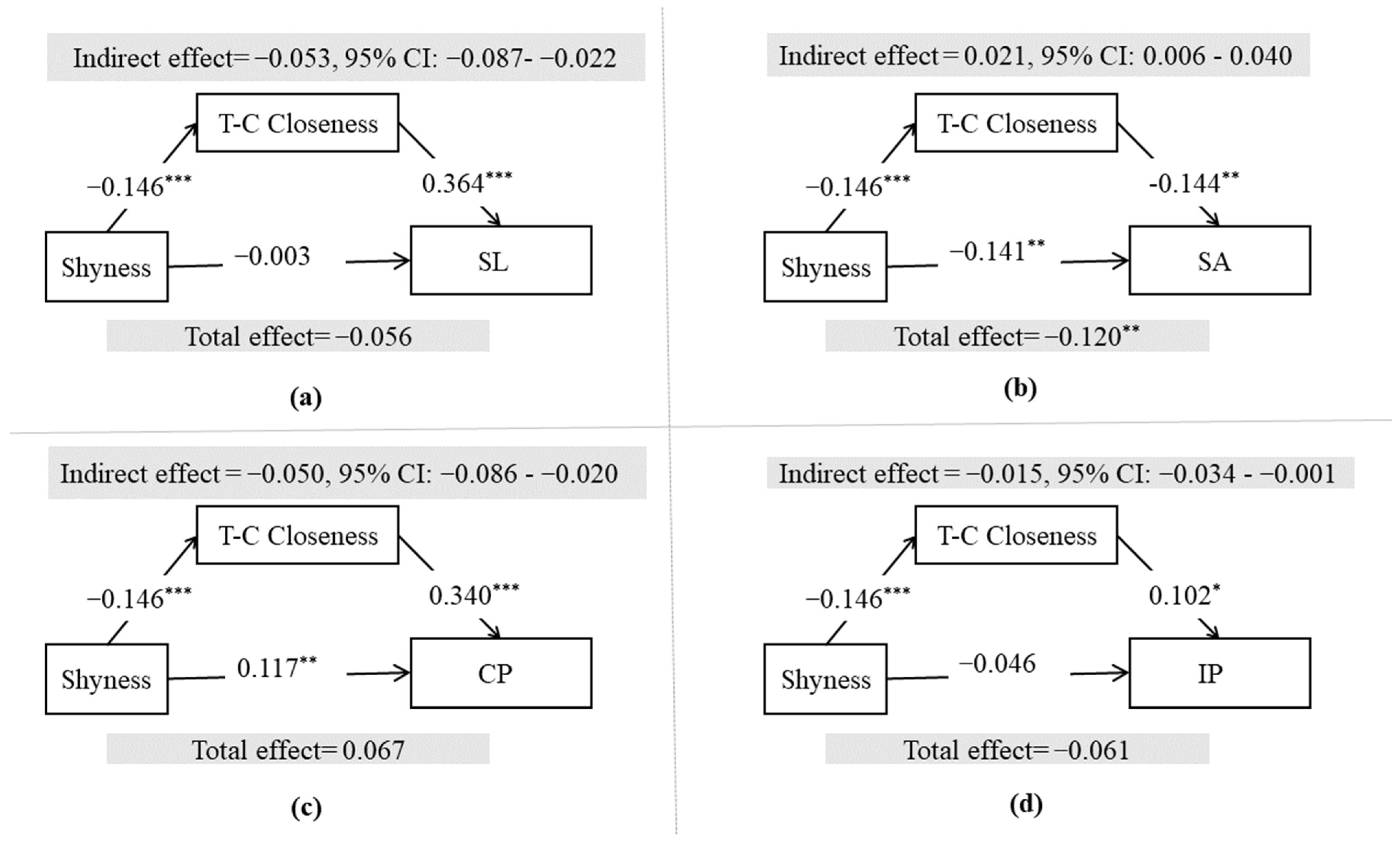

3.3. Testing for Mediating Effects

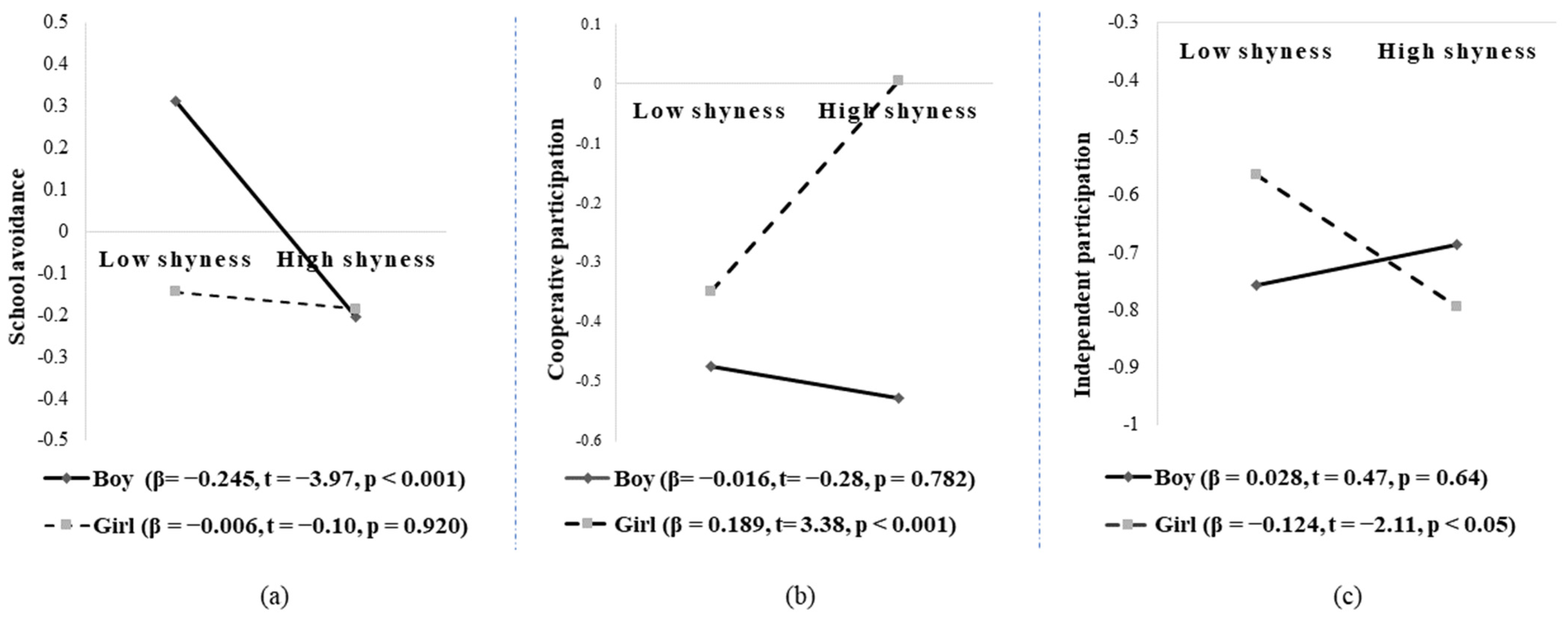

3.4. Testing for Moderating Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. The Direct Effect of Shyness on School Engagement

4.2. The Mediating Role of Teacher–Child Closeness

4.3. The Moderating Role of Child Gender

4.4. Theoretical Implications

4.5. Practical Implications

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G.W.; Dinella, L.M. Continuity and change in early school engagement: Predictive of children’s achievement trajectories from first to eighth grade? J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Coplan, R.J.; Bowker, J.C. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.P.; Wu, J.F.; Chen, Y.M.; Han, L.; Han, P.G.; Wang, P.; Gao, F.Q. Shyness and school adjustment among Chinese preschool children: Examining the moderating effect of gender and teacher-child relationship. Early Educ. Dev. 2015, 26, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G.; Buhs, E.; Seid, M. Children’s Initial Sentiments About Kindergarten: Is School Liking an Antecedent of Early Classroom Participation and Achievement? Merrill-Palmer Q. 2000, 46, 255–279. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, E.A.; Belmont, M.J. Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. J. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 85, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, S.H.; Ladd, G.W. Children’s interpersonal behaviors and the teacher-child relationship. Dev. Psychol. 1998, 34, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhs, E.S.; Ladd, G.W. Peer rejection as antecedent of young children’s school adjustment: An examination of mediating processes. Dev. Psychol. 2001, 37, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Prakash, K.; O’Neil, K.; Armer, M. Do you “want” to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Dev. Psychol. 2004, 40, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. Variable Effects of children’s aggression, social withdrawal, and prosocial leadership as functions of teacher beliefs and behaviors. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.S.L.; Rubin, K.H. European American and Mainland Chinese mothers’ responses to aggression and social withdrawal in preschoolers. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2004, 28, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cen, G.; Li, D.; He, Y. Social functioning and adjustment in Chinese children: The imprint of historical time. Child Dev. 2005, 76, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Farver, J.A.M.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, Q. Chinese children’s conceptions of shyness: A prototype approach. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2008, 54, 515–544. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Farver, J.A.M.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, Q. Three types of shyness in Chinese children and the relation to effortful control. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Arbeau, K.A. The stresses of a “brave new world”: Shyness and school adjustment in kindergarten. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2008, 22, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Coplan, R.J. Exploring processes linking shyness and academic achievement in childhood. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2010, 25, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Arbeau, K.A.; Armer, M. Don’t fret, be supportive! Maternal characteristics linking child shyness to psychosocial and school adjustment in kindergarten. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2008, 36, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, C.; Swanson, J.; Lemery-Chalfant, K. Kindergartners’ temperament, classroom engagement, and student–teacher relationship: Moderation by effortful control. Soc. Dev. 2012, 21, 558–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggum-Wilkens, N.D.; Valiente, C.; Swanson, J.; Lemery-Chalfant, K. Children’s shyness, popularity, school liking, cooperative participation, and internalizing problems in the early school years. Early Child. Res. Q. 2014, 29, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosacki, S.L.; Coplan, R.J.; Rose-Krasnor, L.; Hughes, K. Elementary school teachers’ reflections on shy children in the classroom. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 57, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beidel, D.C.; Turner, S.M. Shy Children, Phobic Adults: Nature and Treatment of Social Phobia; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M. Shyness in the classroom and home. In International Handbook of Social Anxiety: Concepts, Research, and Interventions Relating to the Self and Shyness; Crozier, W.R., Alden, L.E., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal, M.R.; Peisner-Feinberg, E.; Pianta, R.; Howes, C. Development of academic skills from preschool through second grade: Family and classroom predictors of developmental trajectories. J. Sch. Psychol. 2002, 40, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C. Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pianta, R.C.; Stuhlman, M.W. Teacher–child relationships and children’s success in the first years of school. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 33, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijs, J.T.; Koomen, H.M.Y. Task-related interactions between kindergarten children and their teachers: The role of emotional security. Infant Child Dev. 2008, 17, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, L.M.; Cottone, E.A.; Mashburn, A.; Rimm-Kaufman, S.E. Relationships between teachers and preschoolers who are at risk: Contribution of children’s language skills, temperamentally based attributes, and gender. Early Educ. Dev. 2008, 19, 600–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zee, M.; Roorda, D.L. Students’ shyness and affective teacher-student relationships in upper elementary schools: A cross-cultural comparison. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2021, 86, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, B.A. Gender stereotypes in advertising on children’s television in the 1990s: A cross-national analysis. J. Advert. 1998, 27, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doey, L.; Coplan, R.J.; Kingsbury, M. Bashful boys and coy girls: A review of gender differences in childhood shyness. Sex Roles 2014, 70, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colder, C.R.; Mott, J.A.; Berman, A.S. The interactive effects of infant activity level and fear on growth trajectories of early childhood behavior problems. Dev. Psychopathol. 2002, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, B.-B.; Santo, J.B. The relationships between shyness and unsociability and peer difficulties: The moderating role of insecure attachment. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2016, 40, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Coplan, R.J.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Ding, X.; Zhou, Y. Unsociability and shyness in Chinese children: Concurrent and predictive relations with indices of adjustment. Soc. Dev. 2014, 23, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Shyness-inhibition in childhood and adolescence: A cross-cultural perspective. In The Development of Shyness and Social Withdrawal; Rubin, K.H., Coplan, R.J., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 213–235. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Eggum-Wilkens, N.D. Correlates of Shyness and Unsociability During Early Adolescence in Urban and Rural China. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z. Shyness-sensitivity and social, school, and psychological adjustment in rural migrant and urban children in China. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 1499–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. Socioemotional development in Chinese children. In Handbook of Chinese Psychology; Bond, M.H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, D.; Eggumwilkens, N.D. Do cultural orientations moderate the relation between Chinese adolescents’ shyness and depressive symptoms? It depends on their academic achievement. Soc. Dev. 2019, 28, 908–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; French, D.C. Children’s social competence in cultural context. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, D. Empowerment, interaction and identity: Suburban farmers’ urbanization under the perspective of role theory. Sociol. Stud. 2009, 24, 28–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, D.; Fu, R.; Coplan, R.J. Relations of shyness–sensitivity and unsociability with adjustment in middle childhood and early adolescence in suburban Chinese children. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2017, 41, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ooi, L.L.; Wu, M.; Li, Y.; Coplan, R.J.; Cao, Y. Exploring the Links between Unsociability, Parenting Behaviors, and Socio-Emotional Functioning in Young Children in Suburban China. Early Educ. Dev. 2020, 32, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Coplan, R.J.; Gao, Z.-Q.; Xu, P.; Li, L.; Zhang, H. Assessment and implications of social withdrawal subtypes in young Chinese children: The Chinese version of the Child Social Preference Scale. J. Genet. Psychol. 2016, 177, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C. Student-Teacher Relationship Scale: Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, J. The Reciprocal Relations Between Teachers’ Perceptions of Children’s Behavior Problems and Teacher-Child Relationships in the First Preschool Year. J. Genet. Psychol. 2011, 172, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, G.W.; Kochenderfer, B.J.; Coleman, C.C. Classroom peer acceptance, friendship, and victimization: Distinct relational systems that contribute uniquely to children’s school adjustment? Child Dev. 1997, 68, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladd, G.W.; Herald-Brown, S.L.; Reiser, M. Does chronic classroom peer rejection predict the development of children’s classroom participation during the grade school years? Child Dev. 2008, 79, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, P.A.; Tix, A.P.; Barron, K.E. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sette, S.; Zava, F.; Baumgartner, E.; Laghi, F.; Coplan, R.J. Exploring the Role of Play Behaviors in the Links between Preschoolers’ Shyness and Teacher-Child Relationships. Early Educ. Dev. 2022, 33, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J.; Fritz, M.S. Mediation Analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.A. Language performance, academic performance, and signs of shyness: A comprehensive review. In The Development of Shyness and Social Withdrawal; Rubin, K.H., Coplan, R.J., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 179–212. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan, R.J.; Schneider, B.H.; Matheson, A.; Graham, A. “Play skills” for shy children: Development of a social skills facilitated play early intervention program for extremely inhibited preschoolers. Infant Child Dev. 2010, 19, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Liu, J.; Cao, J.; Chen, X.; Li, D. Shyness and school adjustment in Chinese children: The roles of teachers and peers. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2017, 32, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bowker, J.C.; Liu, J.; Li, D.; Chen, X. Relations between shyness and psychological adjustment in Chinese children: The role of friendship quality. Infant Child Dev. 2020, 30, e2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Number of Indicators | Factor Loading Range | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shyness | 7 | 0.701–0.802 | 0.883 | 0.885 | 0.525 |

| Teacher–Child Closeness | 11 | 0.620–0.728 | 0.886 | 0.884 | 0.411 |

| School Liking | 5 | 0.721–0.882 | 0.874 | 0.873 | 0.581 |

| School Avoidance | 4 | 0.724–0.803 | 0.833 | 0.834 | 0.557 |

| Cooperative Participation | 7 | 0.708–0.814 | 0.891 | 0.890 | 0.537 |

| Independent Participation | 4 | 0.724–0.803 | 0.833 | 0.834 | 0.557 |

| Variables | Female | Male | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children | |||

| Grade: n (%) | |||

| Lower | 74 | 86 | 160 (30%) |

| Middle | 106 | 129 | 235 (44%) |

| Upper | 60 | 77 | 137 (26%) |

| Total | 240 (45%) | 292 (55%) | 532 (100%) |

| Age (year): M (SD) | 4.32 (0.70) | 4.27 (0.61) | 4.29 (0.65) |

| Parents | |||

| Education level: n (%) | |||

| Junior high school and below | 138 (26%) | 106 (20%) | 244 (23%) |

| Senior high school or vocational school | 208 (39%) | 192 (36%) | 400 (38%) |

| Three-year college | 96 (18%) | 133 (25%) | 229 (22%) |

| University/Bachelor’s | 85 (16%) | 90 (17%) | 175 (16%) |

| Master’s and above | 5 (1%) | 11 (2%) | 16 (1%) |

| Total | 532 (100%) | 532 (100%) | 1064 (100%) |

| Age (year): M (SD) | 30.25 (3.21) | 31.32 (4.05) | 30.79 (3.85) |

| Teachers | |||

| Education level: n (%) | |||

| Senior high school or vocational school | 4 | 0 | 4 (9%) |

| University/Bachelor’s | 37 | 2 | 39 (87%) |

| Master’s and above | 2 | 0 | 2 (4%) |

| Total | 43 (96%) | 2 (4%) | 45 (100%) |

| Age (year): M (SD) | - | - | 28.26 (7.42) |

| Work experience (year): M (SD) | - | - | 5.33 (5.62) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | 0.154 *** | 0.083 † | 0.145 *** | −0.138 ** | 0.215 *** | 0.042 |

| 2. Shyness | - | −0.155*** | −0.064 | −0.119 ** | 0.061 | −0.070 | |

| 3. Closeness | - | 0.417 *** | −0.120 ** | 0.359 *** | 0.187 *** | ||

| 4. School liking | - | −0.529 *** | 0.469 *** | 0.376 *** | |||

| 5. School avoidance | - | −0.203 *** | −0.180 *** | ||||

| 6. CP | - | 0.383 *** | |||||

| 7. IP | - | ||||||

| M | - | 14.41 | 37.73 | 20.80 | 8.15 | 25.75 | 12.37 |

| SD | - | 5.38 | 5.75 | 3.26 | 3.12 | 5.32 | 3.08 |

| DVs | Predictors | R2 | F | β | SE | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | SL | Grade | 0.087 | 25.05 *** | 0.287 | 0.182 | 6.91 *** |

| Shyness | −0.056 | 0.025 | −1.34 | ||||

| SA | Grade | 0.034 | 6.17 *** | −0.033 | 0.180 | −0.76 | |

| Shyness | −0.120 | 0.025 | −2.79 ** | ||||

| CP | Grade | 0.055 | 15.43 *** | 0.227 | 0.301 | 5.37 *** | |

| Shyness | 0.067 | 0.042 | 1.59 | ||||

| IP | Grade | 0.096 | 28.06 *** | 0.302 | 0.171 | 7.30 *** | |

| Shyness | −0.061 | 0.024 | −1.48 | ||||

| Step 2 | Closeness | Grade | 0.102 | 30.13 *** | 0.280 | 0.044 | −3.55 *** |

| Shyness | −0.146 | 0.317 | 6.80 *** | ||||

| Step 3 | SL | Grade | 0.206 | 45.69 *** | 0.185 | 0.177 | 4.58 *** |

| Shyness | −0.003 | 0.024 | −0.06 | ||||

| Closeness | 0.364 | 0.023 | 8.90 *** | ||||

| SA | Grade | 0.034 | 6.17 *** | 0.007 | 0.186 | 0.17 | |

| Shyness | −0.141 | 0.025 | −3.26 ** | ||||

| Closeness | −0.144 | 0.025 | −3.18 ** | ||||

| CP | Grade | 0.159 | 33.21 *** | 0.132 | 0.297 | 3.17 ** | |

| Shyness | 0.117 | 0.040 | 2.90 ** | ||||

| Closeness | 0.340 | 0.040 | 8.06 *** | ||||

| IP | Grade | 0.105 | 20.70 *** | 0.273 | 0.177 | 6.37 *** | |

| Shyness | −0.046 | 0.024 | −1.11 | ||||

| Closeness | 0.102 | 0.023 | 2.34 * |

| Predictors | SL | SA | CP | IP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Shyness | 0.016 | 0.28 | −0.245 | −3.97 *** | −0.016 | −0.28 | 0.028 | 0.47 |

| Closeness | 0.357 | 8.71 *** | −0.142 | −3.16 ** | 0.317 | 7.64 *** | 0.105 | 2.41* |

| Gender | 0.211 | 2.67 ** | −0.221 | −2.54 * | 0.330 | 4.11 *** | 0.042 | 0.49 |

| Shyness × Gender | −0.070 | −0.90 | 0.239 | 2.79 ** | 0.205 | 2.58 * | −0.152 | −1.82 † |

| Grade | 0.240 | 4.45 *** | 0.019 | 0.32 | 0.165 | 3.01 ** | 0.364 | 6.33 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Fang, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, H. Shyness and School Engagement in Chinese Suburban Preschoolers: A Moderated Mediation Model of Teacher–Child Closeness and Child Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074270

Wu Y, Fang M, Wu J, Chen Y, Li H. Shyness and School Engagement in Chinese Suburban Preschoolers: A Moderated Mediation Model of Teacher–Child Closeness and Child Gender. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):4270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074270

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yunpeng, Min Fang, Jianfen Wu, Yingmin Chen, and Hui Li. 2022. "Shyness and School Engagement in Chinese Suburban Preschoolers: A Moderated Mediation Model of Teacher–Child Closeness and Child Gender" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 4270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074270

APA StyleWu, Y., Fang, M., Wu, J., Chen, Y., & Li, H. (2022). Shyness and School Engagement in Chinese Suburban Preschoolers: A Moderated Mediation Model of Teacher–Child Closeness and Child Gender. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074270