Tuberculosis and Migrant Pathways in an Urban Setting: A Mixed-Method Case Study on a Treatment Centre in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

- Migrant—a person who is born outside Portugal independently of legal status. In Portugal TB in foreign-born citizens is accounted by country of birth.

- Recent migrant—a migrant being diagnosed with TB within a 2 year-period following arrival in Portugal [TB diagnosis within two years following arrival (yes)]

- Long-term migrant—a migrant being diagnosed of TB after 2 year-period following arrival in Portugal. [Total TB foreign-born per year minus TB diagnosis within two years following arrival]

- Autochthonous TB–TB in Portuguese-born individuals.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

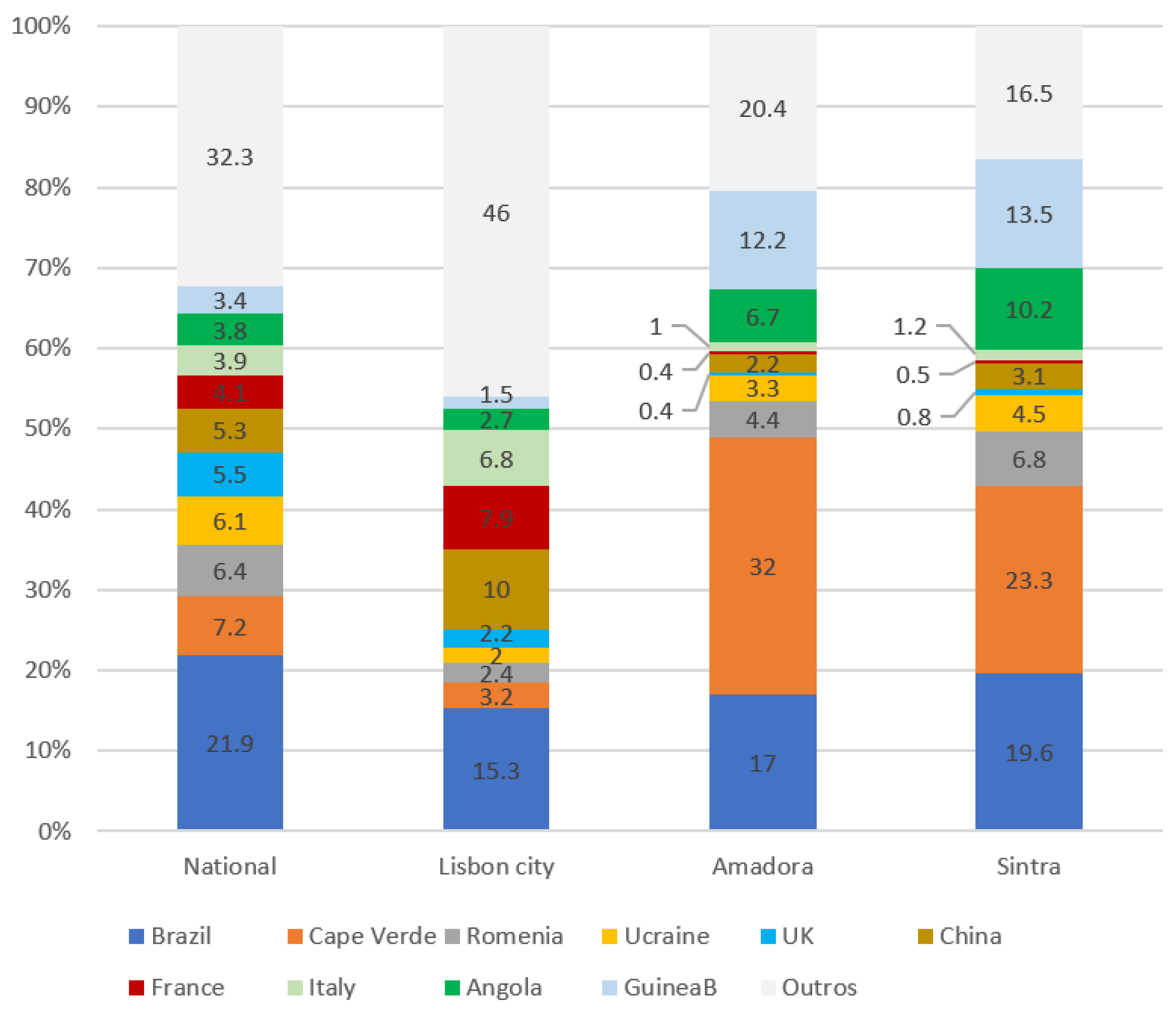

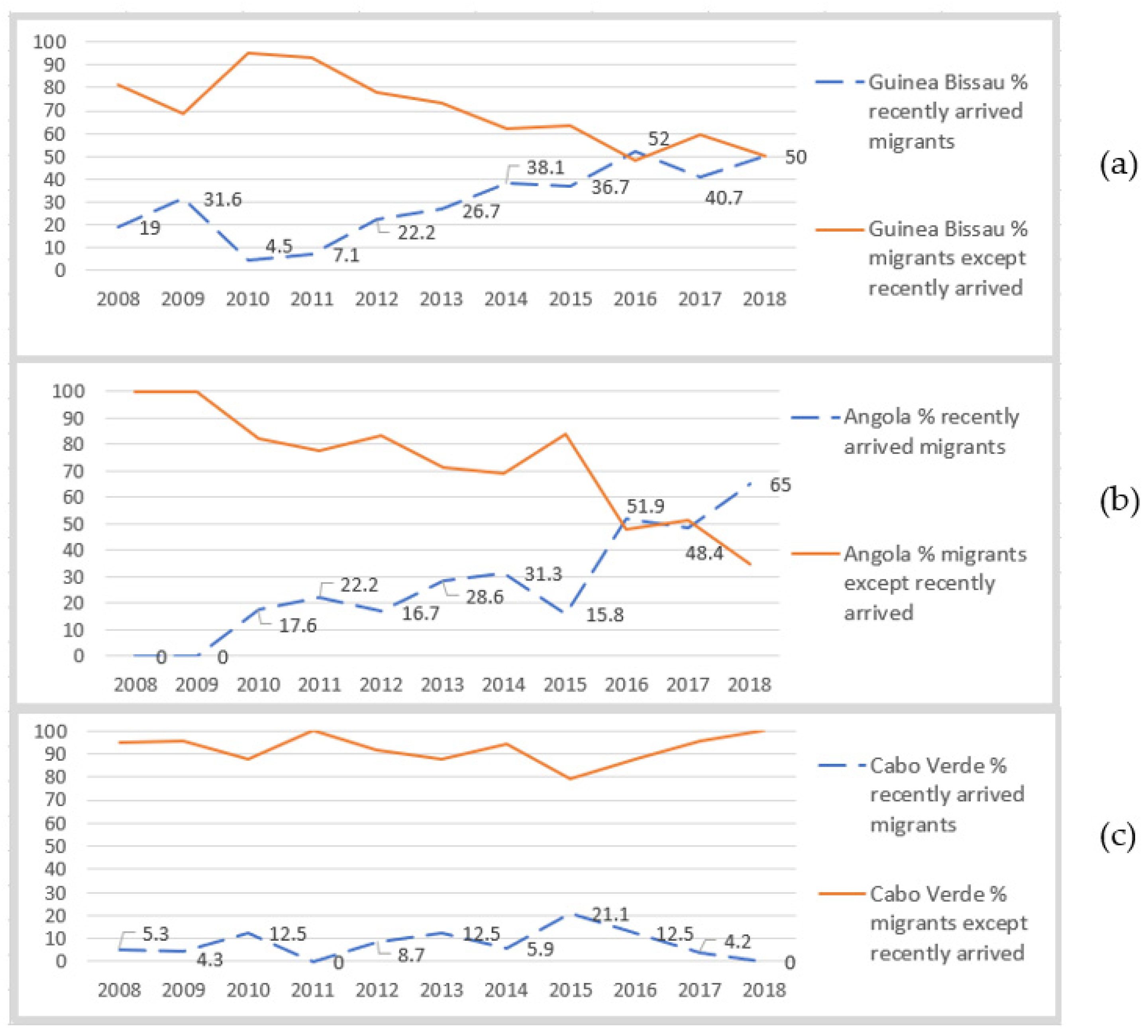

3.1. Secondary Quantitative Data Analysis

3.2. Primary Qualitative Data Analysis

“They could give me medication not appropriate for me… I have heard of people… taking medication not appropriate for their pathology and having consequences, sometimes even more serious… it was the case of my father, he almost died… these issues I have seen there, made me risk everything and come to check what is going on with me, to be sure. Then I thought about Portugal”.(P1)

“(…) In Senegal… they gave me treatment and I felt better, I thought everything was fine, but then I continued with pain, it got worse, I could not even get out of bed in the morning, walk, or work, and then I came here”.(P4)

“If it wasn’t through Primary Health Care it would be too expensive, and I could not make it…”[P10 took advice from a friend]

“Private clinics… there you go ask for an appointment, the doctor comes register things, you go, you have results, the doctor explains it, then you go on with other things…”(P8)

“I chose Portugal because here I know how to speak the language, and also because it is the country which colonised Guinea-Bissau, I have more rights here than in other countries…”(P3)

“I thought about Portugal as the easiest… I have family here and the local language is Portuguese… there is a connection… we have a very good impression as people doing consultations return, cured, healed… I saw myself in this condition, I came to have a good consultation and get cured”(P1)

“I was not so worried, as if I were in Angola… I would have thought “I will die tomorrow”. As I was here, I did not worry… I felt taken care of…”(P2)

“There… if you don’t have someone in the family who is a doctor, or someone important… you die easily”.(P7)

“Many times, we just have the consultation itself… there is no medicine in the hospital, and sometimes even syringes, needles, alcohol to disinfect… patient’s family has to buy it in the pharmacy out of the hospital and it is very complicated… we must buy all disposable materials”(P5)

“To give birth I prefer the clinic, there is a better service because you are going to pay… in the public hospital there is no service… they respond badly to people, they don’t help people”.(P4)

“In Angola it was difficult… to acquire medicines was a fight… to get it I would visit several pharmacies, contact anonymous resellers… the prescribed medicines were not available in the pharmacies. Sometimes I would remain 2–3 weeks without medication… and when we had the drugs, medicines were very expensive”.(P1)

“In this hospital… medicine must be given to patients for free, but I think they sold it… you have to do “business” with nurses or technicians … they themselves are the ones taking from the hospital and selling”.(P7)

“To get medicines is the most difficult, people say come “tomorrow”, “tomorrow”, and if you pay, there is medication, especially in the case of TB, because HIV drugs are still for free”(P10)

“I was not confident; I was not sure… I have seen people sick of TB… but the way it happened to me, to fall and faint, I have never seen it. I was not believing it… because TB on the head, I have never heard of it”(P8)

“Until now they don’t believe it, first they start with my lifestyle-“She eats fruits, eats on time, she takes care” … then I did not have contact with infectiology... We are Africans… they prefer to look at other little things than believe X had TB… even with the report… it worries me until now. Myself I did not believe it was TB”[P11, talking about her workplace]

“I was very scared, lots of fear, of not holding on until here, because I went to the healthcare centre and when I arrived there, I did not say anything to the doctor [HIV diagnosis]. I just told it here. I just said I was sick of tuberculosis… I feel a lot of shame”(P3)

“Everything was upside down, my daughter had to drop school and come here rapidly, financially we had to toughen up to be able to stay here”(P11)

“I cannot deny anything because they said everything was proven by laboratory exams, then I accepted it”(P4)

“In Portugal it is better, there is variety, it is cheaper also [food]… For instance, here people eat meat every day, there is fruit with vitamins. In Guinea [Bissau] we eat meat every 2, 3 or 6 months… only fish, but of low quality. There are vegetables but no fruit. There, it is more expensive, even after money conversion”(P4)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Topic Guide for Semi-Structured Interviews with TB Patients

- Imagine a situation where you got sick (or a family member, your children), how was it? What did you do?

- Regarding the previous situation, where did you search for help? How did you go to the place (transport)? Which exams did you do and how was it (cost, waiting time, complexity)? How did you get the medicines?

- How would you qualify the healthcare you received? (Waiting times, satisfaction…)

- Tell me how was the beginning of this illness episode? How was it for you?

- Where did you search for help? (Consultations, exams, treatment, family support)

- What were the main difficulties you have faced? (Transport, financial, literacy…)

- What has helped you in this process?

- Since you started feeling sick until the doctors told you were sick of tuberculosis how long has it passed? Tell me how did you live this period of your life, how was it for you?

- What did you feel when doctors told you this diagnosis?

- Who was the first person you told the diagnosis? How was it?

- How was it at work?

- What have been the most difficult for you in this process?

- What has helped you the most?

- What do you think about the healthcare you have received? (3 positive and 3 negative aspects)

- Is there something you would like to be different?

- What are the motifs leading you to migrate, can you explain it to me?

- Which reasons influences the choice of Portugal?

- How was the preparation process for the trip (work, visa…)? How long did it take?

- What were the main obstacles that emerged in the process?

- Which help/support did you get? (Work, family, institutions…)

- How was the arrival in Portugal?

- When did you have the first consultation in Portugal? And where was it?

- Did you have to go to the migration office? Tell me how it was.

- In this period, you have been in Portugal, which were the main difficulties you faced? Tell me 2 or 3.

- What has helped you the most?

- What do you miss the most in your country? Are you organizing the return home?

Appendix B

| P1 | PHC–CDP Treatment initiation in Angola in private clinic, 2 consultations with 2 different clinicians until diagnosis, 2 months of treatment facing financial and logistic constraints to acquire drugs. Decision to come to Portugal in VFF condition. It takes 1 month in Portugal to search for healthcare. Entry point: primary healthcare whereafter directly referred to CDP, restarting TB treatment. |

| P2 | Screening at refugee asylum-ER–H–CDP Symptoms started in Angola, being neglected, and seen as “normal” for months. One consultation was done, and “vitamins” were prescribed. Family imposed travelling to Portugal where the participant entered a refugee asylum. In the context of a screening program, participant presented an abnormal X-ray being referred to the emergency room, then hospitalised, then followed ambulatory consultations and TB treatment was started. |

| P3 | PHC–CDP HIV diagnosis was performed in the context of pregnancy in Brazil. Antiretroviral treatment was taken during pregnancy and stopped afterwards, because of perception of good health. Cough symptoms started, 2 months later, initial private healthcare was sought, then referred to public healthcare for hospitalisation with AIDS and TB. Because of lack of family support and difficulties to take care of the baby, participant decided to come to Europe (not Portugal) to regroup with family after hospitalisation. HIV medication was given for three months in order to travel. Language barrier was the main motivation to move to Portugal. Entry point: PHC being directly referred to the CDP and forward referred to HIV consultations. |

| P4 | Private clinic–CDP–ER–H–CDP Pain symptoms first appeared in Guinea-Bissau where TB diagnosis was suggested, however there was no trust in the proposed diagnosis. Decision to travel to Dakar-Senegal as VFF, for better healthcare where participant has treated and got partially improved. When symptoms restarted, the decision to come to Portugal was made. Participant came legally through bilateral agreement between countries for treatment of medical conditions (evacuated). HIV was diagnosed once hospitalised in Portugal. Entry point: private clinic where participant followed several medical diagnostic exams being referred to CDP and to the ER, being hospitalised, then referred back to the CDP. |

| P5 | ER–H–CDP Studying for master’s degree was the reason to come to Portugal. Six months following arrival, during a period of financial difficulties, symptoms began. Participant resorts directly to the ER of a known hospital (because of studies), being hospitalised. Entry point: ER being hospitalised then referred to the CDP |

| P6 | ER–H–CDP The reason to come to Portugal was family re-grouping and the desire to start a new life. Participant was working and living outside Lisbon. The illness process obliged the participant to seek increased family support, causing participant to move to Lisbon. Following a sudden pain episode, after months of feeling sick, participant resorts directly to the ER and was hospitalised. |

| P7 | PHC–ER–H–CDP In Angola participant finds out about HIV in the context of health check for the desire of getting pregnant. Antiretroviral treatment was initiated and stopped, by then cough had started but diagnostic studies were inconclusive. Participant decided to restart antiretroviral treatment and gets better. Participant also starts TB medication, but stops as she travels to Portugal, where she had lived previously, with the aim to start a new life with better healthcare conditions. In the context of pregnancy, in Portugal, participant starts to feel sick again. She consults primary healthcare, however as referral takes a long time participant decides to go to the ER, being hospitalised. |

| P8 | Ambulance–ER–H–CDP Participant came to Portugal, a frequent travel destination, for shopping and tourism as VFF. In a public place, participant suddenly fell ill (inaugural convulsion), being taken to the ER and then hospitalised. |

| P9 | ER–H–CDP In Angola, participant experiences strong backpain while on vacations. Initially private healthcare was sought, and several treatments were given without being effective. Traditional medicine was tried but not effective either. Healthcare proved expensive and ineffective. Thus, participant travelled to Portugal as VFF, in search of better healthcare. Entry point: ER, being hospitalised. |

| P10 * | PHC–CDP In Angola HIV positive participant had been previously diagnosed with TB; difficulties in acquiring medication led to treatment discontinuation. Participants’ child was diagnosed of HIV and treatment was initiated. Participant explains strong secondary effect from child’s antiretroviral treatment, reason which motivated travelling to Portugal in search of better healthcare for her child. Participant was advised by a friend, who had experienced good results, to do so. Entry point: primary healthcare then referred to CDP. Participant’s child was hospitalised. |

| P11 | Private clinic–ER–H–CDP Cough and fever started, and being a health professional, participant initially sought care via colleagues initiating treatment with little result. Having health professionals as relatives, participant was advised to attend a private healthcare consultation, without effective treatment. They decided to seek specialist healthcare in the capital, Luanda, however as condition worsened, participant decided to come to Portugal where participant was familiar with private healthcare. Following a specialist private consultation, participant was referred to the public system for hospitalisation. Entry point: private consultation then referred to the ER of a public hospital, then hospitalised then referred to the CDP. |

| P12 * | PHC–ER–CDP Following belly pain, participant seeks private healthcare in Angola where surgery was proposed but refused, as it was deemed too expensive. Participant had a prebooked flight to Portugal for tourism. Upon arrival, participant felt progressively weaker and attended a consultation in PHC. Participant had lived in Portugal previously. Ambulatory exams were requested in PHC and participant was referred to the ER, then sent home, then returned to the ER, underwent ambulatory exams at hospital level, and was referred to the CDP afterwards. |

| P13 | Private clinic–Private ER–Private H–CDP Experiencing cough symptoms and anorexia started years earlier. Participant sought medical consultations in Angola, and in Namibia as VFF, being diagnosed with a mental condition. Symptoms subsequently wore off. Following a chest-X-ray for another reason, participant is advised to travel to Portugal and search for a medical team in a private hospital. Participant is submitted to lung surgery in Portugal and returns to Angola. Follow-up consultation in Portugal took longer than advised, and after one and half years, participant is submitted to a new surgery. A few months after the second surgery, participant runs a high fever, resorts to ER, and is hospitalised in private hospital where TB is suspected, then participant is referred to CDP. |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tiemersma, E.W.; van der Werf, M.J.; Borgdorff, M.W.; Williams, B.G.; Nagelkerke, N.J.D. Natural history of tuberculosis: Duration and fatality of untreated pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV negative patients: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, M.; Behr, M.A.; Dowdy, D.; Dheda, K.; Divangahi, M.; Boehme, C.C.; Ginsberg, A.; Swaminathan, S.; Spigelman, M.; Getahun, H.; et al. Tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Narasimhan, P.; Wood, J.; Macintyre, C.R.; Mathai, D. Risk factors for tuberculosis. Pulm. Med. 2013, 2013, 828939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lönnroth, K.; Jaramillo, E.; Williams, B.G.; Dye, C.; Raviglione, M. Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: The role of risk factors and social determinants. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 2240–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, R.; Lönnroth, K.; Carvalho, C.; Lima, F.; Carvalho, A.C.C.; Muñoz-Torrico, M.; Centis, R. Tuberculosis, social determinants and co-morbidities (including HIV). Pulmonology 2018, 24, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Implementing the End TB Strategy: The Essentials; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrii Dudnyk, D.C. Mission impossible: The end TB strategy. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2018, 22, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.G.M.; Barreto, M.L.; Glaziou, P.; Medley, G.F.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Wallinga, J.; Squire, S.B. End TB strategy: The need to reduce risk inequalities. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, H.; LaFleur, M.; Alarcón, D. Concepts of Inequality. Development Issues No1. Development Strategy and Policy Analysis Unit in the Development Policy and Analysis Division of UN/DESA. 2015, pp. 1–2. Available online: www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wess/ (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Carter, D.J.; Glaziou, P.; Lönnroth, K.; Siroka, A.; Floyd, K.; Weil, D.; Raviglione, M.; Houben, R.M.G.J.; Boccia, D. The impact of social protection and poverty elimination on global tuberculosis incidence: A statistical modelling analysis of sustainable development goal 1. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2018, 6, e514–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Tuberculosis Surveillance and Monitoring in Europe 2021–2019 Data; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021.

- Rechel, B.; Mladovsky, P.; Devillé, W. Monitoring migrant health in Europe: A narrative review of data collection practices. Health Policy 2012, 105, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Tuberculosis Surveillance and Monitoring in Europe 2018–2016 Data; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018.

- Machado, R.; Reis, S.; Esteves, S.; Sousa, P.; Rosa, A.P. Relatório de Imigração, Fronteiras e Asilo; Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteira: Oeiras, Portugal, 2019.

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) [Statistics Portugal]. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0008337&contexto=pi&selTab=tab0 (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Noori, T.; Hargreaves, S.; Greenaway, C.; van der Werf, M.; Driedger, M.; Morton, R.L.; Hui, C.; Requena-Mendez, A.; Agbata, E.; Myran, D.T.; et al. Strengthening screening for infectious diseases and vaccination among migrants in Europe: What is needed to close the implementation gaps? Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 39, 101715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, V.; Jaff, D.; Shah, N.S.; Frick, M. Tuberculosis, human rights and ethics considerations along the route of highly vulnerable migrant from Sub-Saharan Africa to Europe. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2017, 21, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carballo, M. Communicable diseases. In Health and Migration in the European Union: Better Health for All in an Inclusive Society; Fernandes, A., Pereira Miguel, J., Eds.; Instituto Nacional de Saúde Doutor Ricardo Jorge: Lisbon, Portugal, 2009; Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- Creatore, M.I.; Lam, M.; Wobeser, W.L. Patterns of tuberculosis risk over time among recent immigrants to Ontario, Canada. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2005, 9, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sotgiu, G.; Dara, M.; Centis, R.; Matteelli, A.; Solovic, I.; Gratziou, C.; Rendon, A.; Battista Migliori, G. Breaking the barriers: Migrants and tuberculosis. Press. Med. 2017, 46, e5–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Taylor, B.M. Modelling the time to detection of urban tuberculosis in two big cities in Portugal: A spatial survival analysis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2016, 20, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, A.M.; Garcia, A.C.; Gama, A.; Abecasis, A.B.; Viveiros, M.; Dias, S. Tuberculosis care for migrant patients in Portugal: A mixed methods study with primary healthcare providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, G.; Aldridge, R.W.; Caylá, J.A.; Haas, W.H.; Sandgreen, A.; van Hest, N.A. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in big cities of the European Union and European Economic area countries. Euro Surveill. 2014, 19, 20728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couceiro, L.; Santana, P.; Nunes, C. Pulmonary tuberculosis and risk factors in Portugal: A spatial analysis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2011, 15, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdy, D.W.; Golub, J.E.; Chaisson, R.E.; Saraceni, V. Heterogeneity in tuberculosis transmission and the role of geographic hotspots in propagating epidemics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9557–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolinário, D.; Ribeiro, A.I.; Krainski, E.; Sousa, P.; Abranches, M.; Duarte, R. Tuberculosis inequalities and socio-economic deprivation in Portugal. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2017, 21, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick Schiller, N.; Çaǧlar, A. Towards a comparative theory of locality in migration studies: Migrant incorporation and city scale. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2009, 35, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Cities and Local Governments Committee on Social Inclusion Participatory Democracy and Human Rights; Lechner, E. Inclusive Cities Observatory “The Critical Urban Areas Programme in Cova Da Moura; Centro de Estudos Sociais, Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, D.G. Segregação socioespacial e características socioeconómicas da área metropolitana de Lisboa: O caso dos imigrantes dos países africanos de língua oficial portuguesa. Cad. Estud. Sociais 2018, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatório Português dos Sistemas de Saúde (OPSS). Saúde Um Direito Humano. Relatório de Primavera 2019; OPPS: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Entidade Reguladora da Saúde (ERS). Acesso de Imigrantes a Prestação de Cuidados de Saúde no Serviço Nacional de Saúde [Acess to Healthcare for Migrants]. Available online: https://www.ers.pt/pt/utentes/perguntas-frequentes/faq/acesso-de-imigrantes-a-prestacao-de-cuidados-de-saude-no-servico-nacional-de-saude/ (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research—Design and Methods. Second Edition; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- ACES Amadora. Guia de Acolhimento Ao Utente; ACES: Amadora, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Database of Contemporaneous Portugal (PORDATA). Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/https://www.pordata.pt/Municipios/População+residente+total+e+por+grandes+grupos+etários-390 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras. SEFSTAT—Portal de Estatística [SEFSTAT Statistics]. Available online: https://sefstat.sef.pt/forms/home.aspx (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Ministério da Saúde. Relatório Anual: Acesso Aos Cuidados de Saúde Nos Estabelecimentos Do SNS e Entidades Convencionadas em 2018. Lei n.º 15/2014, de 21 de março; Ministério da Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018; pp. 1–330.

- Tudor Hart, J. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971, 297, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, R.; Doran, T.; Asaria, M.; Gupta, I.; Mujica, F.P. The inverse care law re-examined: A global perspective. Lancet 2021, 397, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Enhancing the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Serv. Res. 1999, 34, 1209–1224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluye, P.; Hong, Q.N. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: Mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Ann. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areias, C.; Briz, T.; Nunes, C. Pulmonary tuberculosis space–time clustering and spatial variation in temporal trends in Portugal, 2000–2010: An updated analysis. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015, 143, 3211–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.; Dias, S.; Nunes, C. Tuberculose e imigração em Portugal: Características sociodemográficas, clínicas e fatores de risco tuberculosis and immigration in Portugal: Socio-demographic, clinical characteristic and risk factors. Rev. Migrações 2017, 14, 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ploubidis, G.B.; Palmer, M.J.; Blackmore, C.; Lim, T.; Manissero, D.; Sandgren, A.; Semenza, J.C. Social determinants of tuberculosis in Europe: A prospective ecological study. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorslaer, E.; Masseria, C.; Koolman, X. Inequalities in access to medical care by income in developed countries. CMAJ 2006, 174, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, A.N.; Morais, S.; Peleteiro, B. Healthcare services utilization among migrants in Portugal: Results from the National Health Survey 2014. J. Immigr. Minor. Heal. 2019, 21, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, N.A.; Davidow, A.L.; Winston, C.A.; Chen, M.P.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Katz, D.J. A national study of socioeconomic status and tuberculosis rates by country of birth, United States, 1996–2005. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Gomes, P.; Taveira, R.; Silva, C.; Maltez, F.; Macedo, R.; Costa, C.; Couvin, D.; Rastogi, N.; Viveiros, M.; et al. Insights on the mycobacterium tuberculosis population structure associated with migrants from Portuguese-speaking countries over a three-year period in greater Lisbon, Portugal: Implications at the public health level. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 71, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittalis, S.; Piselli, P.; Contini, S.; Gualano, G.; Alma, M.G.; Tadolini, M.; Piccioni, P.; Bocchino, M.; Matteelli, A.; Bonora, S.; et al. Socioeconomic status and biomedical risk factors in migrants and native tuberculosis patients in Italy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Garcia, D. Residential segregation and the epidemiology of infectious diseases. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 1143–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnroth, K.; Glaziou, P.; Weil, D.; Floyd, K.; Uplekar, M.; Raviglione, M. Beyond UHC: Monitoring health and social protection coverage in the context of tuberculosis care and prevention. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.; Pavignani, E.; Guerreiro, C.S.; Neves, C. Can we halt health workforce deterioration in failed states? Insights from Guinea-Bissau on the nature, persistence and evolution of its HRH crisis. Hum. Resour. Health 2017, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, P.; Vita, D. Challenges to tuberculosis control in Angola: The narrative of medical professionals. J. Public Heal. 2018, 40, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, M.L.; Rando-Segura, A.; Moreno, M.M.; Soley, M.E.; Igual, E.S.; Bocanegra, C.; Olivas, E.G.; Eugénio, A.N.; Zacarias, A.; Katimba, D.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Cubal, Angola: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2019, 23, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehre, F.; Otu, J.; Kendall, L.; Forson, A.; Kwara, A.; Kudzawu, S.; Kehinde, A.O.; Adebiyi, O.; Salako, K.; Baldeh, I.; et al. The emerging threat of pre-extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in West Africa: Preparing for large-scale tuberculosis research and drug resistance surveillance. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosa, L.; Da Silva, L.; Mendes, D.V.; Sifna, A.; Mendes, M.S.; Riccardi, F.; Colombatti, R. Feasibility and effectiveness of tuberculosis active case-finding among children living with tuberculosis relatives: A cross-sectional study in Guinea-Bissau. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 9, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, I.; Sant’Anna, C. Screening and follow-up of children exposed to tuberculosis Cases, Luanda, Angola. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2011, 15, 1359–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, R.; Jensen, P.; Hess, K.; Mooney, L.; Milligan, J. Substandard and falsified anti-tuberculosis drugs: A preliminary field analysis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2013, 17, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingori, P.; Peeters Grietens, K.; Abimbola, S.; Ravinetto, R. Poor-quality medical products: Social and ethical issues in accessing “quality” in Global Health. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porskrog, A.; Bjerregaard-Andersen, M.; Oliveira, I.; Joaquím, L.C.; Camara, C.; Andersen, P.L.; Rabna, P.; Aaby, P.; Wejse, C. Enhanced tuberculosis identification through 1-month follow-up of smear-negative tuberculosis suspects. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2011, 15, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.M.; Havik, P.J.; Craveiro, I. The circuits of healthcare: Understanding healthcare seeking behaviour—A qualitative study with tuberculosis patients in Lisbon, Portugal. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, M.A. A imigração PALOP em Portugal. O caso dos doentes evacuados. Forum Sociológico 2012, 22, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchin, M.; Orazbayev, S. Social networks and the intention to migrate. World Dev. 2018, 109, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direção-Geral da Saúde/Serviços Nacional de Saúde. Tuberculose » Centros de Diagnóstico Pneumológico. Available online: https://www.dgs.pt/paginas-de-sistema/saude-de-a-a-z/tuberculose1/centros-de-diagnostico-pneumologico.aspx (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Gimeno-Feliu, L.A.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Diaz, E.; Poblador-Plou, B.; Macipe-Costa, R.; Prados-Torres, A. Global healthcare use by immigrants in Spain according to morbidity burden, area of origin, and length of stay. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, S.; Holmes, A.H.; Saxena, S.; Le Feuvre, P.; Farah, W.; Shafi, G.; Chaudry, J.; Khan, H.; Friedland, J.S. Charging systems for migrants in primary care: The experiences of family doctors in a high-migrant area of London. J. Travel Med. 2008, 15, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Craig, G.M.; Daftary, A.; Engel, N.; O’Driscoll, S.; Ioannaki, A. Tuberculosis stigma as a social determinant of health: A systematic mapping review of research in low incidence countries. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 56, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulo, B.X.; Peixoto, B. Emotional distress patients with several types of tuberculosis. A pilot study with patients from the sanatorium hospital of Huambo. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 2016, 5, S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luis, S.F.; Kamp, N.; Mitchell, E.M.H.; Henriksen, K.; Van Leth, F. Health-seeking norms for tuberculosis symptoms in Southern Angola: Implications for behaviour change communications. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2011, 15, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, L.V.; Saunders, M.J.; Zegarra, R.; Evans, C.; Alegria-Flores, K.; Guio, H. Why wait? The social determinants underlying tuberculosis diagnostic delay. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meeteren, M.; Pereira, S. Beyond the “migrant network”? Exploring assistance received in the migration of Brazilians to Portugal and The Netherlands. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2018, 19, 925–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, J.E.; Orcau, Á.; Millet, J.P.; Ros, M.; Gil, S.; Caylà, J.A. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in immigrants in a large city with large-scale immigration (1991–2013). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programa Nacional para a Tuberculose [PNT]. Relatório de Vigilância e Monitorização Da Tuberculose Em Portugal—Dados Definitivos 2018/19[Internet]; Direção-Geral da Saúde: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020; Available online: https://www.dgs.pt/documentos-e-publicacoes/relatorio-de-vigilancia-e-monitorizacao-da-tuberculose-em-portugal-dados-definitivos-2020-pdf.aspx (accessed on 31 January 2022).

| Estimated TB Incidence Rate + | # Notified TB Cases | TB-HIV Co-Infection + | TB Treatment Coverage ^ | Treatment Success Rate ~ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | 16 (13–18) | 1445 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 88% (76–100) | 71% |

| Brazil | 45 (38–52) | 82,930 | 5 (4.3–5.8) | 78% (67–91) | 69% |

| Cabo Verde | 39 (30–50) | 210 | 5.1 (3.1–7.6) | 95% (75–120) | 89% |

| Romania | 64 (54–74) | 7698 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 58% (50–69) | 84% |

| Ukraine | 73 (49–102) | 19,521 | 16 (11–22) | 55% (39–82) | 79% |

| UK | 6.9 (6.3–7.6) | 4458 | 0.24 (0.09–0.46) | 89% (81–98) | 78% |

| China | 59 (50–68) | 633,156 | 0.84 (0.71–0.98) | 74% (64–87) | 94% |

| France | 8.2 (7.2–9.2) | 4606 | 0.42 (0.32–0.52) | 83% (73–94) | 12% |

| Italy | 6.6 (5.7–7.6) | 2287 | 0.34 (0.19–0.54) | 54% (47–63) | - |

| Angola | 350 (225–503) | 66,058 | 41 (26–59) | 55% (38–85) | 69% |

| Guinea-Bissau | 361 (234–516) | 2561 | 114 (74–164) | 36% (25–55) | 89% |

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | 87 | 94 | 113 | 82 | 100 | 76 | 115 | 112 | 111 | 76 | 65 | 1031 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 21 | 19 | 22 | 28 | 27 | 15 | 21 | 30 | 25 | 27 | 18 | 253 |

| Cabo Verde | 19 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 23 | 24 | 17 | 19 | 16 | 24 | 11 | 226 |

| Angola | 13 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 24 | 14 | 16 | 19 | 27 | 31 | 20 | 214 |

| S. Tomé | 2 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 34 |

| Brazil | 2 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 34 |

| Mozambique | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 28 |

| Others | 3 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 78 |

| TOTAL | 149 | 165 | 196 | 168 | 197 | 142 | 195 | 196 | 188 | 173 | 129 | 1898 |

| Country of Origin | TB Type | Risk Factor | Legal Status | Reason to Come | Entry Point | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Angola | P | - | SDD | Health | PHC |

| P2 | Angola | Pleural | - | SDD | Live | Screening |

| P3 | Guinea-B | Ganglionar | HIV | SDD | Health | PHC |

| P4 | Guinea-B | Bone/miliar | HIV | SDD | Health | Private clinic |

| P5 | Angola | Pleural | - | User number | Live/Study | ER |

| P6 | Guinea-B | P | - | User number | Live | ER |

| P7 | Angola | Peritoneal | HIV | User number | Health/Live | PHC |

| P8 | Guinea-B | Disseminated | - | User number | Tourism | Ambulance |

| P9 | Angola | Bone | - | SDD | Health | ER |

| P10 * | Angola | P | HIV | SDD | Health | PHC |

| P11 | Angola | P | Health p | SDD | Health | Private clinic |

| P12 * | Angola | Pleural | - | User number | Tourism | PHC |

| P13 | Angola | Pleural | - | User number | Health | Private clinic |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, R.M.; Gonçalves, L.; Havik, P.J.; Craveiro, I. Tuberculosis and Migrant Pathways in an Urban Setting: A Mixed-Method Case Study on a Treatment Centre in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073834

Ribeiro RM, Gonçalves L, Havik PJ, Craveiro I. Tuberculosis and Migrant Pathways in an Urban Setting: A Mixed-Method Case Study on a Treatment Centre in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(7):3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073834

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Rafaela M., Luzia Gonçalves, Philip J. Havik, and Isabel Craveiro. 2022. "Tuberculosis and Migrant Pathways in an Urban Setting: A Mixed-Method Case Study on a Treatment Centre in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 7: 3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073834

APA StyleRibeiro, R. M., Gonçalves, L., Havik, P. J., & Craveiro, I. (2022). Tuberculosis and Migrant Pathways in an Urban Setting: A Mixed-Method Case Study on a Treatment Centre in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, Portugal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3834. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073834