Determinants of Utilization of Institutional Delivery Services in Zambia: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Study Design and Sample

2.4. Variable Measurement

2.4.1. Outcome Variable

2.4.2. Explanatory Variables

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.6. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participants

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division: Executive Summary. Geneva PP—Geneva: WHO. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327596 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Ogundele, O.J.; Pavlova, M.; Groot, W. Examining trends in inequality in the use of reproductive health care services in Ghana and Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambia Statistics Agency (ZamStats); Ministry of Health (MOH); University Teaching Hospital Virology Laboratory—UTH-VL; ICF. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2018. 2020. Available online: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR361/FR361.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/ (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Titaley, C.R.; Dibley, M.J.; Roberts, C.L. Factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Indonesia: Results of Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2002/2003 and 2007. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sibiya, M.N.; Ngxongo, T.S.P.; Bhengu, T.J. Access and utilisation of antenatal care services in a rural community of eThekwini district in KwaZulu-Natal. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigatu, A.M.; Gelaye, K.A. Factors associated with the preference of institutional delivery after antenatal care attendance in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ignacio Ruiz, J.; Nuhu, K.; Tyler McDaniel, J.; Popoff, F.; Izcovich, A.; Martin Criniti, J. Inequality as a powerful predictor of infant and maternal mortality around the world. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140796. [Google Scholar]

- Mrisho, M.; Obrist, B.; Schellenberg, J.A.; Haws, R.A.; Mushi, A.K.; Mshinda, H.; Tanner, M.; Schellenberg, D. The use of antenatal and postnatal care: Perspectives and experiences of women and health care providers in rural southern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Highlights and Key Messages from the World Health Organization’s 2016 Global Recommendations for Routine Antenatal Care. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259947/WHO-RHR-18.02-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Hagos, S.; Shaweno, D.; Assegid, M.; Mekonnen, A.; Afework, M.F.; Ahmed, S. Utilization of institutional delivery service at Wukro and Butajera districts in the Northern and South Central Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajaari, J.; Masanja, H.; Weiner, R.; Abokyi, S.A.; Owusu-Agyei, S. Impact of Place of Delivery on Neonatal Mortality in Rural Tanzania. Int. J. MCH AIDS 2012, 1, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, W.J.; Bell, J.S.; Bullough, C.H. Can Skilled Attendance at Delivery Reduce Maternal Mortality in Developing Countries. Safe Mother. Strateg. A Rev. Evidence 2001, 17, 97–130. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Brodish, P.; Suchindran, C. A regional multilevel analysis: Can skilled birth attendants uniformly decrease neonatal mortality? Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, N.; Bell, S.; Quaiyum, A. Modeling maternal mortality in Bangladesh: The role of misoprostol in postpartum hemorrhage prevention. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Lerberghe, W. The world health report 2008. In Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, O.M.R.; Graham, W.J.; Lancet Maternal Survival Series Steering Group. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: Getting on with what works. Lancet 2006, 368, 1284–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Raja, E.A.; Dhakal, K.B. Skilled Care at Birth among Rural Women in Nepal: Practice and Challenges. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2011, 29, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yaya, S.; Bishwajit, G.; Ekholuenetale, M. Factors associated with the utilization of institutional delivery services in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gebregziabher, N.K.; Zeray, A.Y.; Abtew, Y.T.; Kinfe, T.M.; Abrha, D.T. Factors determining choice of place of delivery: Analytical cross-sectional study of mothers in Akordet town, Eritrea. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya, S.; Bishwajit, G.; Gunawardena, N. Socioeconomic factors associated with choice of delivery place among mothers: A population-based cross-sectional study in Guinea-Bissau. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kibria GM, A.; Ghosh, S.; Hossen, S.; Barsha RA, A.; Sharmeen, A.; Uddin, S.M. Factors affecting deliveries attended by skilled birth attendants in Bangladesh. Matern. Health Neonatol. Perinatol. 2017, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sahoo, J.; Singh, S.V.; Gupta, V.K.; Garg, S.; Kishore, J. Do socio-demographic factors still predict the choice of place of delivery: A cross-sectional study in rural North India. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2015, 5, S27–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoseph, M.; Abebe, S.M.; Mekonnen, F.A.; Sisay, M.; Gonete, K.A. Institutional delivery services utilization and its determinant factors among women who gave birth in the past 24 months in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kifle, M.M.; Kesete, H.F.; Gaim, H.T.; Angosom, G.S.; Araya, M.B. Health facility or home delivery? Factors influencing the choice of delivery place among mothers living in rural communities of Eritrea. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2018, 37, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.M. National Health Surveys and the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use. Med. Care 2008, 46, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-N.; Nong, D.-X.; Wei, B.; Feng, Q.-M.; Luo, H.-Y. The impact of predisposing, enabling, and need factors in utilization of health services among rural residents in Guangxi, China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rashid, M.; Antai, D. Socioeconomic position as a determinant of maternal healthcare utilization: A population-based study in Namibia. J. Res. Health Sci. 2014, 14, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Country Profile: Zambia. Background Statistics. 2006. Available online: https://healthmarketinnovations.org/sites/default/files/Final_%20CHMI%20Zambia%20profile.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- United Nations. World Population Prospects—Population Division. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects. 2019. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Highlights.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- IMF. International Monetary Fund (2019). Zambia. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPGDP@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/ZMB (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- World Bank. The World Bank in Zambia. 2019. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/zambia/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Zambia Health Budget Brief. Lusaka, Zambia. 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/5006/file/UNICEF-Zambia-2019-Health-Budget-Brief.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Phiri, J.; Ataguba, J.E. Inequalities in public health care delivery in Zambia. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chiu, C.; Scott, N.A.; Kaiser, J.L.; Ngoma, T.; Lori, J.R.; Boyd, C.J.; Rockers, P.C. Household saving during pregnancy and facility delivery in Zambia: A cross-sectional study. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshete, T.; Legesse, M.; Ayana, M. Utilization of institutional delivery and associated factors among mothers in rural community of Pawe Woreda northwest Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huda, T.M.; Chowdhury, M.; El Arifeen, S.; Dibley, M.J. Individual and community level factors associated with health facility delivery: A cross sectional multilevel analysis in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutstein, S.O.; Johnson, K. The DHS Wealth Index. DHS Comp Reports No. 6. 2004. Available online: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/CR6/CR6.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- O’Brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, E.; Seid, A.; Gedefaw, G.; Haile, Z.; Ice, G. Association between antenatal care follow-up and institutional delivery service utilization: Analysis of 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asamoah, B.O.; Agardh, A.; Cromley, E.K. Spatial Analysis of Skilled Birth Attendant Utilization in Ghana. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2014, 6, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teklehaymanot, A.N.; Kebede, A.; Hassen, K. Factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization in Ethiopia. Int. J. Women’s Health 2016, 8, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pacagnella, R.C.; Cecatti, J.G.; Parpinelli, M.A.; Sousa, M.H.; Haddad, S.M.; Costa, M.L.; Souza, J.P.; Pattinson, R.C.; The Brazilian Network for the Surveillance of Severe Maternal Morbidity Study Group. Delays in receiving obstetric care and poor maternal outcomes: Results from a national multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shahabuddin, A.S.M.; De Brouwere, V.; Adhikari, R.; Delamou, A.; Bardají, A.; Delvaux, T. Determinants of institutional delivery among young married women in Nepal: Evidence from the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2011. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mezmur, M.; Navaneetham, K.; Letamo, G.; Bariagaber HMezmur, M.; Navaneetham, K.; Letamo, G.; Bariagaber, H. Individual, household and contextual factors associated with skilled delivery care in Ethiopia: Evidence from Ethiopian demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesema, G.A.; Mekonnen, T.H.; Teshale, A.B. Individual and community-level determinants, and spatial distribution of institutional delivery in Ethiopia, 2016: Spatial and multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekadu, G.A.; Kassa, G.M.; Berhe, A.K.; Muche, A.; Katiso, N.A. The effect of antenatal care on use of institutional delivery service and postnatal care in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dehingia, N.; Dixit, A.; Atmavilas, Y.; Chandurkar, D.; Singh, K.; Silverman, J.; Raj, A. Unintended pregnancy and maternal health complications: Cross-sectional analysis of data from rural Uttar Pradesh, India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age | |||

| 15–24 | 3405 | 34.6 | |

| 25–34 | 4224 | 42.9 | |

| 35–39 | 1421 | 14.4 | |

| 40–49 | 791 | 8.0 | |

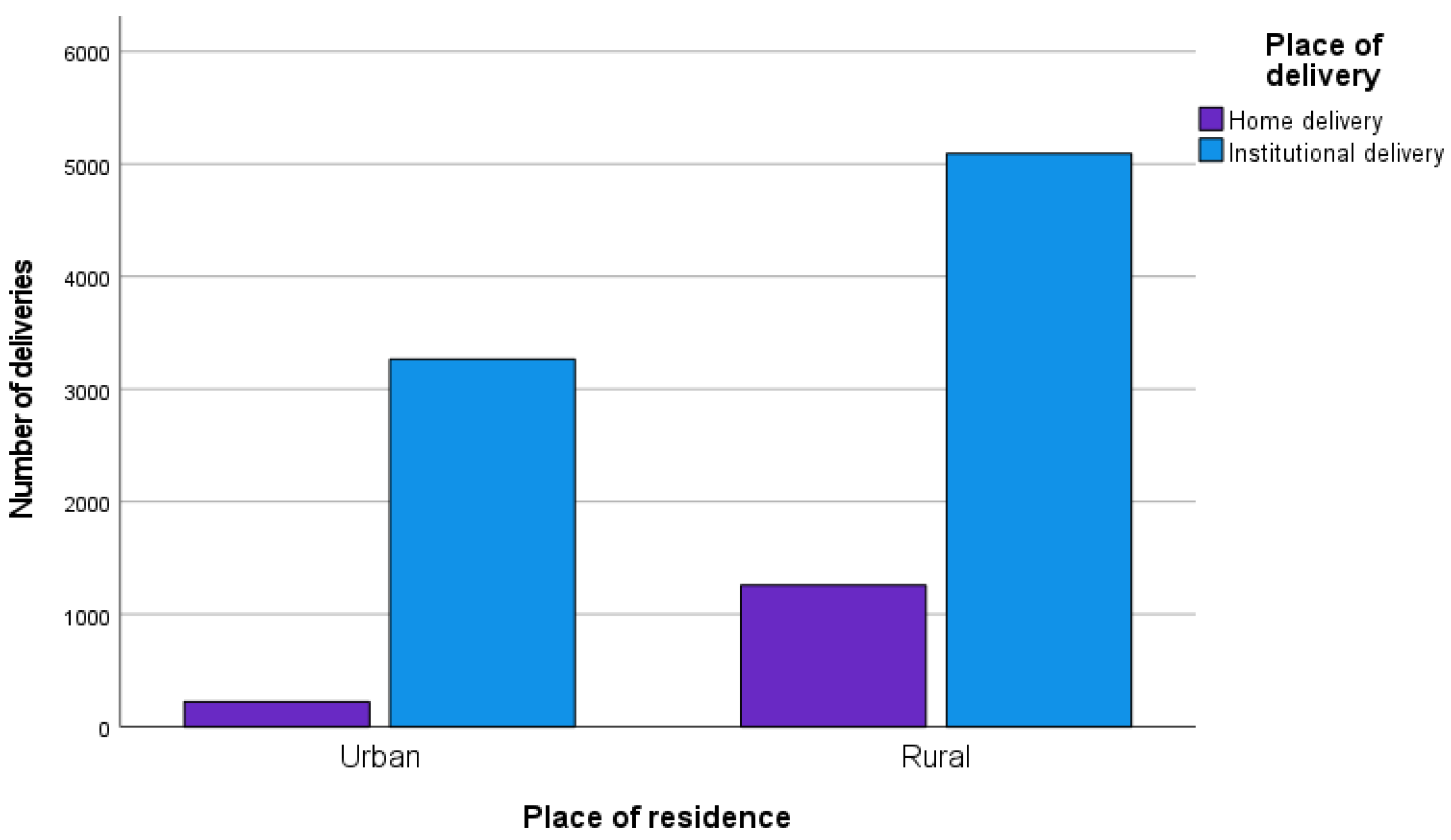

| Place of residence | |||

| Urban | 3489 | 35.5 | |

| Rural | 6352 | 64.5 | |

| Woman’s education | |||

| No formal education | 996 | 10.1 | |

| Primary | 5008 | 50.9 | |

| Secondary/higher | 3837 | 39.0 | |

| Husband’s education | |||

| No education | 491 | 6.7 | |

| Primary | 2909 | 39.4 | |

| Secondary/higher | 3978 | 53.9 | |

| Religion | |||

| Catholic | 1569 | 15.9 | |

| Protestant | 8111 | 82.4 | |

| Other | 161 | 1.6 | |

| Working status 1 | |||

| No | 5193 | 52.8 | |

| Yes | 4648 | 47.2 | |

| Number of children 2 | |||

| 1 | 3672 | 38.9 | |

| 2 | 4209 | 44.7 | |

| 3 or more | 1545 | 16.4 | |

| Wealth index | |||

| Poor | 4634 | 47.1 | |

| Middle | 1823 | 18.5 | |

| Rich | 3385 | 34.4 | |

| Contraception use decision | |||

| Woman’s decision | 609 | 14.8 | |

| Husband’s decision | 475 | 11.5 | |

| Joint decision | 3038 | 73.7 | |

| ANC 3 | |||

| 1–3 visits | 2531 | 35.2 | |

| 4 visits | 2358 | 32.8 | |

| 5–12 visits | 2293 | 31.9 | |

| Healthcare facility | |||

| No | 2632 | 26.7 | |

| Yes | 7209 | 73.3 | |

| Blood pressure 4 | |||

| No | 348 | 4.8 | |

| Yes | 6897 | 95.2 | |

| Anemia | |||

| No | 6875 | 71.8 | |

| Yes | 2706 | 28.2 | |

| Institutional delivery 5 | |||

| No | 1482 | 15.1 | |

| Yes | 8359 | 84.9 |

| Variable | Institutional Delivery (ID) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women with ID | Women without ID | ||||

| % | (95% CI) | % | (95% CI) | ||

| Sociodemographic variables | |||||

| Woman’s age | |||||

| 15–24 | 36.0 | (34.5–37.6) | 26.7 | (24.1–29.6) | <0.001 |

| 25–34 | 42.5 | (40.9–44.1) | 45.2 | (42.0–48.4) | |

| 35–39 | 14.1 | (12.7–15.6) | 16.3 | (14.2–18.7) | |

| 40–49 | 7.4 | (6.6–8.2) | 11.7 | (9.8–14.1) | |

| Place of residence | |||||

| Urban | 39.1 | (35.5–42.8) | 15.0 | (11.3–19.7) | <0.001 |

| Rural | 60.9 | (57.2–64.5) | 85.0 | (80.3–88.7) | |

| Woman’s education | |||||

| No formal education | 8.2 | (7.2–9.2) | 21.3 | (17.1–26.2) | <0.001 |

| Primary | 49.1 | (47.1–51.1) | 61.1 | (56.9–65.1) | |

| Secondary/higher | 42.8 | (40.8–44.8) | 17.6 | (14.5–21.3) | |

| Husband’s education | |||||

| No education | 5.5 | (4.7–6.5) | 12.6 | (9.4– 16.7 | <0.001 |

| Primary | 36.6 | (34.7–38.6) | 54.8 | (50.3–59.2) | |

| Secondary/higher | 57.9 | (55.8–60.0) | 32 | (28.3–37.2) | |

| Religion | |||||

| Catholic | 16.1 | (14.4–17.9) | 15.2 | (12.1–19.0) | 0.87 |

| Protestant | 82.3 | (80.3–48.1) | 83.2 | (79.5–86.4) | |

| Other | 1.7 | (1.1–2.4) | 1.5 | (0.8–3.0) | |

| Working status 1 | |||||

| No | 52.6 | (50.6–54.7) | 53.5 | (49.0–57.9) | 0.71 |

| Yes | 47.4 | (45.3–49.4) | 46.5 | (42.1–51.0) | |

| Number of children 2 | |||||

| 1 | 40.9 | (39.2–42.7) | 28.2 | (25.4–31.3) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 44.0 | (42.4–45.6) | 48.3 | (45.1–51.6) | |

| 3 or more | 15.1 | (13.6–16.8) | 23.4 | (20.3–26.8) | |

| Wealth index | |||||

| Poor | 43.1 | (40.1–46.1) | 69.7 | (65.2–73.8) | < 0.001 |

| Middle | 18.8 | (17.2–20.5) | 16.9 | (14.4–19.8) | |

| Rich | 38.1 | (35.3–41.0) | 13.4 | (10.3–17.2) | |

| Contraception use decision | |||||

| Woman’s decision | 14.6 | (12.8–16.6) | 16.3 | (12.6–20.7) | 0.05 |

| Husband’s decision | 11.0 | (9.5–12.8) | 14.7 | (11.2–19.2) | |

| Joint decision | 74.4 | (72.0–76.7) | 69.0 | (63.9–73.7) | |

| Healthcare-related variables | |||||

| ANC 3 | |||||

| 1–3 visits | 33.3 | (31.7–35.1) | 48.7 | (44.5–53.0) | <0.001 |

| 4 visits | 33.8 | (32.3–35.2) | 26.2 | (23.3–29.3) | |

| 5–12 visits | 32.9 | (31.3–34.6) | 25.0 | (21.5–29.0) | |

| Healthcare facility | |||||

| No | 25.8 | (23.8–27.9) | 32.0 | (27.6–36.7) | 0.002 |

| Yes | 74.2 | (72.1–76.2) | 68.0 | (63.3–72.4) | |

| Blood pressure 4 | |||||

| No | 3.8 | (3.2–4.6) | 11.8 | (8.2–16.8) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 96.2 | (95.4–96.8) | 88.2 | (83.2–91.8) | |

| Anemia | |||||

| No | 71.9 | (70.3–73.5) | 70.9 | (67.5–74.1) | 0.54 |

| Yes | 28.1 | (26.5–29.7) | 29.1 | (25.9–32.5) | |

| Variable | Crude Analysis | Adjusted Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||

| Woman’s age | ||||

| 15–24 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25–34 | 0.70 | 0.61–0.80 | 1.11 | 0.66–1.87 |

| 35–39 | 0.64 | 0.54–0.76 | 1.05 | 0.69–1.62 |

| 40–49 | 0.48 | 0.38–0.57 | 0.79 | 0.49–1.28 |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 0.28 | 0.24–0.32 | 0.55 | 0.30–0.98 |

| Women’s education | ||||

| No education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Primary | 2.10 | 1.80–2.44 | 1.38 | 0.97–1.99 |

| Secondary/higher | 6.32 | 5.27–7.60 | 1.76 | 1.04–2.99 |

| Husband’s education | ||||

| No formal education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Primary | 2.66 | 2.17–3.28 | 1.29 | 0.93–1.78 |

| Secondary/higher | 4.05 | 2.77–5.91 | 1.83 | 1.09–3.05 |

| Number of children 1 | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 0.71 | 0.58–0.87 | 0.83 | 0.56–1.22 |

| 3 or more | 0.45 | 0.36–0.56 | 0.78 | 0.50–1.19 |

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poor | 1 | 1 | ||

| Middle | 2.56 | 1.92–3.41 | 1.75 | 0.96–3.19 |

| Rich | 4.60 | 3.38–6.26 | 2.31 | 1.27–4.22 |

| Contraception use decision | ||||

| Woman’s decision | 1 | 1 | ||

| Husband’s decision | 1.20 | 0.90–1.61 | 1.11 | 0.83–1.67 |

| Joint decision | 1.44 | 1.04–1.99 | 1.23 | 0.75–1.76 |

| Healthcare-related variables | ||||

| ANC 2 | ||||

| 1–3 visits | 1 | 1 | ||

| 4 visits | 1.02 | 0.82–1.27 | 1.20 | 0.85–1.71 |

| 5–12 visits | 1.92 | 1.53–2.41 | 2.33 | 1.66–3.26 |

| Healthcare facility | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.35 | 1.12–1.64 | 1.21 | 0.84–1.76 |

| Blood pressure 3 | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 3.37 | 2.24–5.08 | 2.15 | 1.32–2.66 |

| Anemia | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.95 | 0.84–1.08 | 1.15 | 0.84–1.56 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rashid, M.; Chowdhury, M.R.K.; Kader, M.; Hiswåls, A.-S.; Macassa, G. Determinants of Utilization of Institutional Delivery Services in Zambia: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053144

Rashid M, Chowdhury MRK, Kader M, Hiswåls A-S, Macassa G. Determinants of Utilization of Institutional Delivery Services in Zambia: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):3144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053144

Chicago/Turabian StyleRashid, Mamunur, Mohammad Rocky Khan Chowdhury, Manzur Kader, Anne-Sofie Hiswåls, and Gloria Macassa. 2022. "Determinants of Utilization of Institutional Delivery Services in Zambia: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 3144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053144

APA StyleRashid, M., Chowdhury, M. R. K., Kader, M., Hiswåls, A.-S., & Macassa, G. (2022). Determinants of Utilization of Institutional Delivery Services in Zambia: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 3144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053144