A Neurobiological Framework for the Therapeutic Potential of Music and Sound Interventions for Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Critical Illness Survivors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aim

3. Methods

4. Results

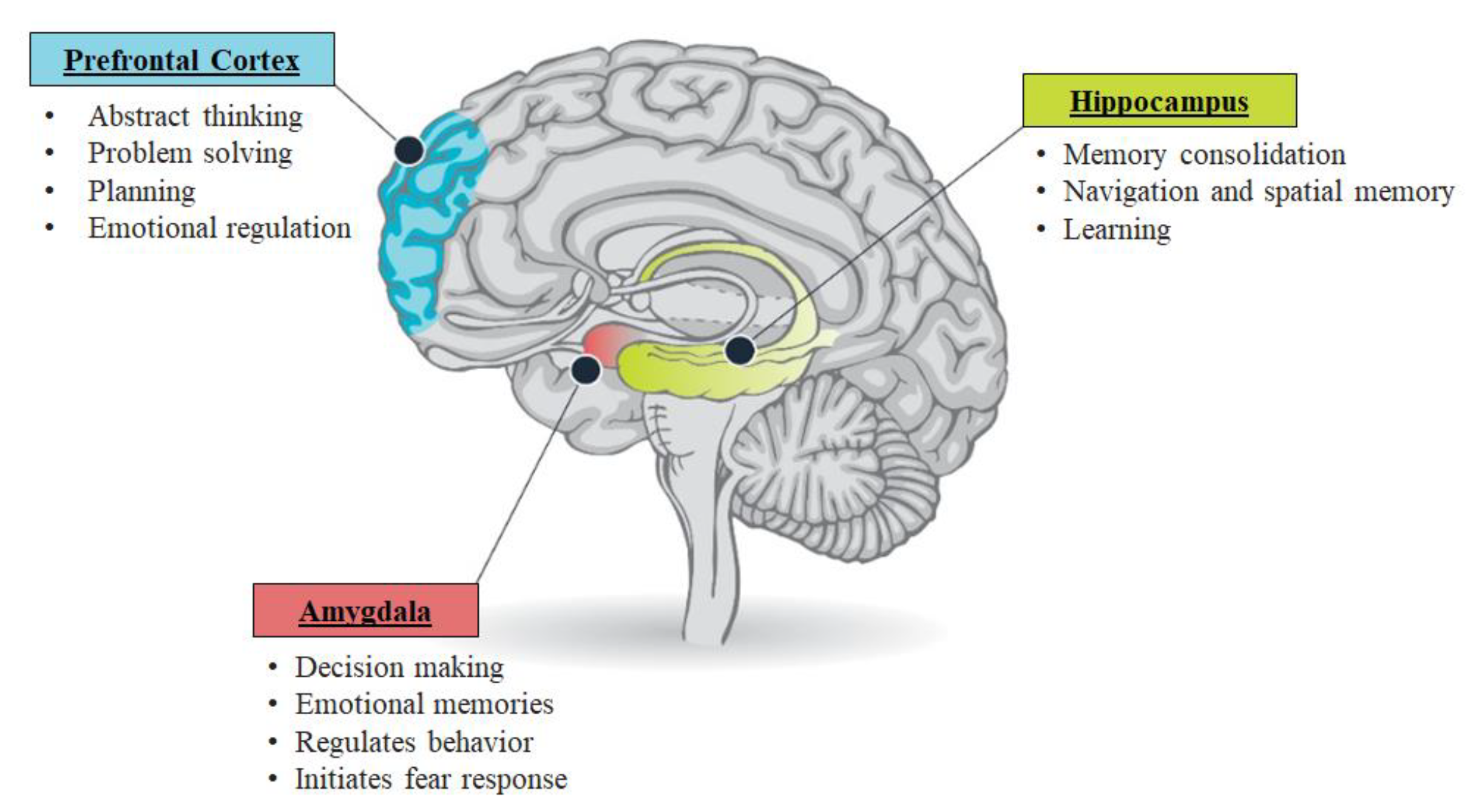

4.1. Pathophysiology of PTSD

4.1.1. The Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

4.1.2. The Amygdalae

4.1.3. The Hippocampus

4.1.4. The Pre-Frontal Cortex

4.2. Music Therapy

4.2.1. Effect of Music in Neuropsychiatric Conditions and PTSD

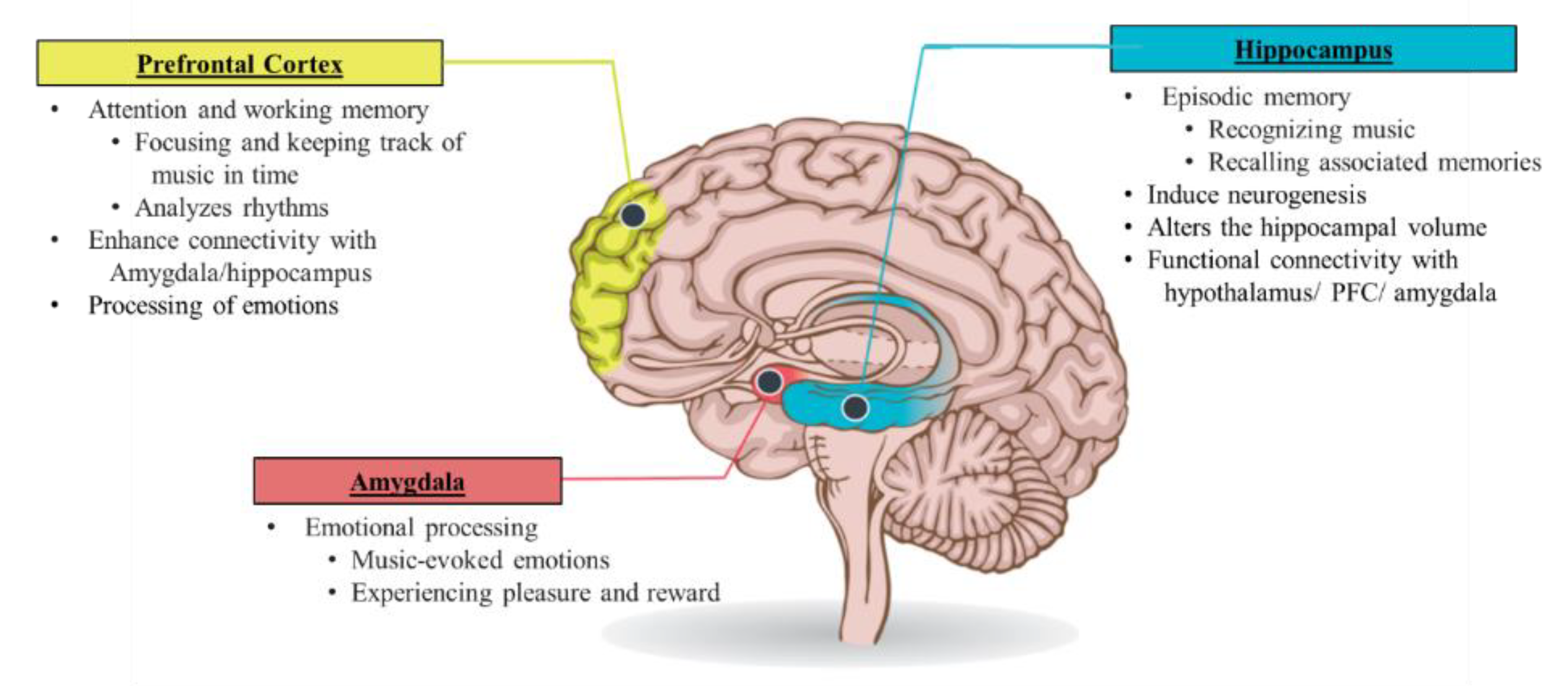

4.2.2. Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of Music in PTSD

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Annachiara, M.; Pratik, P.P.; Timothy, D.G.; Mayur, B.P.; Christopher, G.H.; James, C.J.; Jennifer, L.T.; Rameela, C.; Eugene Wesley, E.; Nathan, E.B. Co-Occurrence of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome Problems Among 406 Survivors of Critical Illness. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.V.; Law, T.J.; Needham, D.M. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needham, D.M.; Davidson, J.; Cohen, H.; Hopkins, R.O.; Weinert, C.; Wunsch, H.; Zawistowski, C.; Bemis-Dougherty, A.; Berney, S.C.; Bienvenu, O.J.; et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: Report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, A.M.; Sricharoenchai, T.; Raparla, S.; Schneck, K.W.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Needham, D.M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: A metaanalysis. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintermann, G.-B.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Petrowski, K.; Strauss, B.; Oehmichen, F.; Pohl, M.; Rosendahl, J. Stress disorders following prolonged critical illness in survivors of severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righy, C.; Rosa, R.G.; da Silva, R.; Kochhann, R.; Migliavaca, C.B.; Robinson, C.C.; Teche, S.P.; Teixeira, C.; Bozza, F.A.; Falavigna, M. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adult critical care survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care (Lond. Engl.) 2019, 23, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydow, D.S.; Gifford, J.M.; Desai, S.V.; Needham, D.M.; Bienvenu, O.J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2008, 30, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, J.; Fortune, G.; Barber, V.; Young, J.D. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: A systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007, 33, 1506–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.C.; Hart, R.P.; Gordon, S.M.; Hopkins, R.O.; Girard, T.D.; Ely, E.W. Post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress symptoms following critical illness in medical intensive care unit patients: Assessing the magnitude of the problem. Crit. Care (Lond. Engl.) 2007, 11, R27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, A.; Nikayin, S.; Hashem, M.D.; Huang, M.; Dinglas, V.D.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Needham, D.M. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D.; Hardy, R.; Howell, D.; Mythen, M. Identifying clinical and acute psychological risk factors for PTSD after critical care: A systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013, 79, 944–963. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, A.F.; Prescott, H.C.; Brett, S.J.; Weiss, B.; Azoulay, E.; Creteur, J.; Latronico, N.; Hough, C.L.; Weber-Carstens, S.; Vincent, J.L.; et al. Long-term outcomes after critical illness: Recent insights. Crit. Care (Lond. Engl.) 2021, 25, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umbrello, M.; Sorrenti, T.; Mistraletti, G.; Formenti, P.; Chiumello, D.; Terzoni, S. Music therapy reduces stress and anxiety in critically ill patients: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019, 85, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D.F.; Moon, Z.; Windgassen, S.S.; Harrison, A.M.; Morris, L.; Weinman, J.A. Non-pharmacological interventions to reduce ICU-related psychological distress: A systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016, 82, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.C.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Girard, T.D.; Brummel, N.E.; Thompson, J.L.; Hughes, C.G.; Pun, B.T.; Vasilevskis, E.E.; Morandi, A.; Shintani, A.K.; et al. Bringing to light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological dysfunction in ICU survivors (BRAIN-ICU) study investigators Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davydow, D.S.; Desai, S.V.; Needham, D.M.; Bienvenu, O.J. Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, T.D.; Shintani, A.K.; Jackson, J.C.; Gordon, S.M.; Pun, B.T.; Henderson, M.S.; Dittus, R.S.; Bernard, G.R.; Ely, E.W. Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms following critical illness requiring mechanical ventilation: A prospective cohort study. Crit. Care (Lond. Engl.) 2007, 11, R28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gezginci, E.; Goktas, S.; Orhan, B.N. The effects of environmental stressors in intensive care unit on anxiety and depression. Nurs. Crit. Care 2020, 27, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gültekin, Y.; Özçelik, Z.; Akıncı, S.B.; Yorgancı, H.K. Evaluation of stressors in intensive care units. Turk. J. Surg. 2018, 34, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGiffin, J.N.; Galatzer-Levy, I.R.; Bonanno, G.A. Is the intensive care unit traumatic? What we know and don’t know about the intensive care unit and posttraumatic stress responses. Rehabil. Psychol. 2016, 61, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, N.; Ören, B.; Üstündag, H. The relationship between stressors and intensive care unit experiences. Nurs. Crit. Care 2020, 25, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amra, S.; John, C.O.; Mikhail, D.; Dziadzko, V.; Rashid, A.; Tarun, D.S.; Rahul, K.; Ann, M.F.; John, D.F.; Ronald, P.; et al. Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors for Long-Term Cognitive Impairment After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kang, J.; Jeong, Y.J. Risk factors for post-intensive care syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust. Crit. Care 2020, 33, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med. Writ. 2015, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccia, M.; D’Amico, S.; Bianchini, F.; Marano, A.; Giannini, A.M.; Piccardi, L. Different neural modifications underpin PTSD after different traumatic events: An fMRI meta-analytic study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016, 10, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flor, H.; Nees, F. Learning, memory, and brain plasticity in posttraumatic stress disorder: Context matters. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2014, 32, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlop, B.W.; Wong, A. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in PTSD: Pathophysiology and treatment interventions. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 89, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.P.; McKlveen, J.M.; Ghosal, S.; Kopp, B.; Wulsin, A.; Makinson, R.; Scheimann, J.; Myers, B. Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Compr. Physiol. 2016, 6, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, B.; McKlveen, J.M.; Herman, J.P. Glucocorticoid actions on synapses, circuits, and behavior: Implications for the energetics of stress. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 35, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, B.; Marwaha, K.; Sanvictores, T.; Ayers, D. Physiology, Stress Reaction. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/ (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Ehlert, U.; Gaab, J.; Heinrichs, M. Psychoneuroendocrinological contributions to the etiology of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and stress-related bodily disorders: The role of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Biol. Psychol. 2001, 57, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheerin, C.M.; Lind, M.J.; Bountress, K.E.; Marraccini, M.E.; Amstadter, A.B.; Bacanu, S.A.; Nugent, N.R. Meta-Analysis of Associations Between Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Genes and Risk of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Trauma Stress 2020, 33, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickel, T. Trauma: HPA Axis [Video]. 2011. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otLHMbNyUx0 (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Sherin, J.E.; Nemeroff, C.B. Post-traumatic stress disorder: The neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 13, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stress and the Brain. Available online: https://turnaroundusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Stress-and-the-Brain_Turnaround-for-Children-032420.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Fuchs, E.; Flügge, G. Adult neuroplasticity: More than 40 years of research. Neural Plast. 2014, 2014, 541870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, A.; Wager, T.D. Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: A meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 1476–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnsten, A.F. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, S.; Friedman, A.R.; Taravosh-Lahn, K.; Kirby, E.D.; Mirescu, C.; Guo, F.; Krupik, D.; Nicholas, A.; Geraghty, A.; Krishnamurthy, A.; et al. Stress and glucocorticoids promote oligodendrogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, D. Using MR to View PTSD’s Effect on the Amygdala and Hippocampus. Radiol. Technol. 2018, 89, 501–504. [Google Scholar]

- McNerney, M.W.; Sheng, T.; Nechvatal, J.M.; Lee, A.G.; Lyons, D.M.; Soman, S.; Liao, C.P.; O’Hara, R.; Hallmayer, J.; Taylor, J.; et al. Integration of neural and epigenetic contributions to posttraumatic stress symptoms: The role of hippocampal volume and glucocorticoid receptor gene methylation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Pellman, B.; Kim, J.J. Stress effects on the hippocampus: A critical review. Learn. Mem. (Cold Spring Harb. N.Y.) 2015, 22, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Yoon, K.S. Stress: Metaplastic effects in the hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 1998, 21, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, K.S.; Dhikav, V. Hippocampus in health and disease: An overview. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2012, 15, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postel, C.; Mary, A.; Dayan, J.; Fraisse, F.; Vallée, T.; Guillery-Girard, B.; Viader, F.; Sayette, V.; Peschanski, D.; Eustache, F.; et al. Variations in response to trauma and hippocampal subfield changes. Neurobiol. Stress 2021, 15, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner-Schmidt, J.L.; Duman, R.S. Hippocampal neurogenesis: Opposing effects of stress and antidepressant treatment. Hippocampus 2006, 16, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, M.W.; Shenton, M.E.; Ciszewski, A.; Kasai, K.; Lasko, N.B.; Orr, S.P.; Pitman, R.K. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 1242–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, M.W.; Williston, S.K.; Paulus, L.A.; Lasko, N.B.; Gurvits, T.V.; Shenton, M.E.; Pitman, R.K.; Orr, S.P. Configural cue performance in identical twins discordant for posttraumatic stress disorder: Theoretical implications for the role of hippocampal function. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 62, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.E. Bilateral hippocampal volume reduction in adults with post-traumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of structural MRI studies. Hippocampus 2005, 15, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, S.J.H.; Kennis, M.; Sjouwerman, R.; van den Heuvel, M.P.; Kahn, R.S.; Geuze, E. Smaller hippocampal volume as a vulnerability factor for the persistence of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 2737–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Neylan, T.C.; Mueller, S.G.; Lenoci, M.; Truran, D.; Marmar, C.R.; Weiner, M.W.; Schuff, N. Magnetic resonance imaging of hippocampal subfields in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, T.J.; Gould, E. Stress, stress hormones, and adult neurogenesis. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 233, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupe, D.W.; Hushek, B.A.; Davis, K.; Schoen, A.J.; Wielgosz, J.; Nitschke, J.B.; Davidson, R.J. Elevated perceived threat is associated with reduced hippocampal volume in combat veterans. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlane, A.C. The long-term costs of traumatic stress: Intertwined physical and psychological consequences. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. (WPA) 2010, 9, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuley, M.T.; Kenny, R.A.; Kirkwood, T.B.; Wilkinson, D.J.; Jones, J.J.; Miller, V.M. A mathematical model of aging-related and cortisol induced hippocampal dysfunction. BMC Neurosci. 2009, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selemon, L.D.; Young, K.A.; Cruz, D.A.; Williamson, D.E. Frontal Lobe Circuitry in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Chronic Stress 2019, 3, 2470547019850166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.S.; Jovanovic, T.; Fani, N.; Ely, T.D.; Glover, E.M.; Bradley, B.; Ressler, K.J. Disrupted amygdala-prefrontal functional connectivity in civilian women with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Ke, J.; Qi, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Lu, G.; Chen, F. Altered functional connectivity of the amygdala and its subregions in typhoon-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.R.; Nearing, K.I.; Ledoux, J.E.; Phelps, E.A. Neural circuitry underlying the regulation of conditioned fear and its relation to extinction. Neuron 2008, 59, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, T.; van Reekum, C.M.; Urry, H.L.; Kalin, N.H.; Davidson, R.J. Failure to regulate: Counterproductive recruitment of top-down prefrontal-subcortical circuitry in major depression. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 8877–8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, H.L.; van Reekum, C.M.; Johnstone, T.; Kalin, N.H.; Thurow, M.E.; Schaefer, H.S.; Jackson, C.A.; Frye, C.J.; Greischar, L.L.; Alexander, A.L.; et al. Amygdala, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex are inversely coupled during regulation of negative affect and predict the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion among older adults. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 4415–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, J.; Sang, L.; Wang, L.; Xie, B.; Wang, J.; Li, M. Negative emotion regulation in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matsuo, K.; Taneichi, K.; Matsumoto, A.; Ohtani, T.; Yamasue, H.; Sakano, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Sadamatsu, M.; Kasai, K.; Iwanami, A.; et al. Hypoactivation of the prefrontal cortex during verbal fluency test in PTSD: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 124, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, A.; Dayan, J.; Leone, G.; Postel, C.; Fraisse, F.; Malle, C.; Vallée, T.; Klein-Peschanski, C.; Viader, F.; de la Sayette, V.; et al. Resilience after trauma: The role of memory suppression. Science 2020, 367, eaay8477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruscia, K.E. Defining Music Therapy, 2nd ed.; Barcelona Publishers: Gilsum, NH, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Music Therapists. About Music Therapy. 2020. Available online: https://www.musictherapy.ca/about-camt-music-therapy/about-music-therapy/ (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Grocke, D.E.; Wigram, T. Receptive Methods in Music Therapy: Techniques and Clinical Applications for Music Therapy Clinicians, Educators, and Students; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA; London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blanaru, M.; Bloch, B.; Vadas, L.; Arnon, Z.; Ziv, N.; Kremer, I.; Haimov, I. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment. Illn. 2012, 4, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Agius, M. The use of Music Therapy in the treatment of Mental Illness and the enhancement of Societal Wellbeing. Psychiatr. Danub. 2018, 30 (Suppl. 7), 595–600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Sui, Y.; Zhu, C.; Yang, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, L.; Ren, L.; Wang, X. Music intervention on cognitive dysfunction in healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 38, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.L.; Springs, S.; Kimmel, H.J.; Gupta, S.; Tiedemann, A.; Sandu, C.C.; Magsamen, S. The Use of Music in the Treatment and Management of Serious Mental Illness: A Global Scoping Review of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 649840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Steen, J.T.; van Soest-Poortvliet, M.C.; van der Wouden, J.C.; Bruinsma, M.S.; Scholten, R.J.; Vink, A.C. Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 5, CD003477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, W.L.; Clark, I.; Tamplin, J.; Bradt, J. Music interventions for acquired brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 1, CD006787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geretsegger, M.; Elefant, C.; Mössler, K.A.; Gold, C. Music therapy for people with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 6, CD004381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geretsegger, M.; Mössler, K.A.; Bieleninik, Ł.; Chen, X.J.; Heldal, T.O.; Gold, C. Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 5, CD004025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.; Mason-Bertrand, A.; Fancourt, D.; Baxter, L.; Williamon, A. How Participatory Music Engagement Supports Mental Well-being: A Meta-Ethnography. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1924–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Witte, M.; Spruit, A.; van Hooren, S.; Moonen, X.; Stams, G.J. Effects of music interventions on stress-related outcomes: A systematic review and two meta-analyses. Health Psychol. Rev. 2020, 14, 294–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, C.H.; Honig, T.J. Health Outcomes of a Series of Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music Sessions: A Systematic Review. J. Music Ther. 2017, 54, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradt, J.; Dileo, C.; Shim, M. Music interventions for preoperative anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD006908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hole, J.; Hirsch, M.; Ball, E.; Meads, C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet (Lond. Engl.) 2015, 386, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chariyawong, P.; Copeland, S.; Mulkey, Z. What is the role of music in the intensive care unit? Southwest Respir. Crit. Care Chron. 2016, 4, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaVolpe, J.D.; Huang, D.T. Is there a role for music in the ICU? Crit. Care 2015, 2016, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullick, J.G.; Kwan, X.X. Patient-directed music therapy reduces anxiety and sedation exposure in mechanically ventilated patients: A research critique. Aust. Crit. Care Off. J. Confed. Aust. Crit. Care Nurses 2015, 28, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofredj, A.; Alaya, S.; Tassaioust, K.; Bahloul, H.; Mrabet, A. Music therapy, a review of the potential therapeutic benefits for the critically ill. J. Crit. Care 2016, 35, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetland, B.; Lindquist, R.; Chlan, L.L. The influence of music during mechanical ventilation and weaning from mechanical ventilation: A review. Heart Lung J. Crit. Care 2015, 44, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlan, L.L.; Heiderscheit, A.; Skaar, D.J.; Neidecker, M.V. Economic Evaluation of a Patient-Directed Music Intervention for ICU Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilatory Support. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, F.A.; Metcalf, O.; Varker, T.; O’Donnell, M. A systematic review of the efficacy of creative arts therapies in the treatment of adults with PTSD. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2018, 10, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Story, K.M.; Beck, B.D. Guided Imagery and Music with female military veterans: An intervention development study. Arts Psychother. 2017, 55, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, C.; d′Ardenne, P.; Sloboda, A.; Scott, C.; Wang, D.; Priebe, S. Group music therapy for patients with persistent post-traumatic stress disorder--an exploratory randomized controlled trial with mixed methods evaluation. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 85, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zergani, E.J.; Naderi, F. The Effectiveness of Music on Quality of Life and Anxiety Symptoms in the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Bustan Hospital of Ahvaz City. Rev. Eur. Stud. 2016, 8, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pourmovahed, Z.; Yassini Ardekani, S.M.; Roozbeh, B.; Ezabad, A.R. The Effect of Non-verbal Music on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Mothers of Premature Neonates. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2021, 26, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, C.; Masthoff, E.; Hakvoort, L. Short-Term Music Therapy Attention and Arousal Regulation Treatment (SMAART) for Prisoners with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Feasibility Study. J. Forensic Psychol. Res. Pract. 2019, 19, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensimon, M.; Amir, D.; Wolf, Y. Drumming through trauma: Music therapy with post-traumatic soldiers. Arts Psychother. 2008, 35, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudstam, G.; Elofsson, U.; Søndergaard, H.P.; Beck, B.D. Trauma-focused group music and imagery with women suffering from PTSD/complex PTSD: A feasibility study. Approaches. Music Ther. Spec. Educ. 2017, 9, 202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Maack, C. Outcomes and Processes of the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (GIM) and Its Adaptations and Psychodynamic Imaginative Trauma Therapy (PITT) for Women with Complex PTSD. Ph.D. Thesis, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 2012. Available online: https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/68395912/Carola_Maack_12.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Beck, B.D.; Messel, C.; Meyer, S.L.; Cordtz, T.O.; Søgaard, U.; Simonsen, E.; Moe, T. Feasibility of trauma-focused Guided Imagery and Music with adult refugees diagnosed with PTSD: A pilot study. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2017, 27, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, B.D.; Meyer, S.L.; Simonsen, E.; Søgaard, U.; Petersen, I.; Arnfred, S.; Tellier, T.; Moe, T. Music therapy was noninferior to verbal standard treatment of traumatized refugees in mental health care: Results from a randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1930960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mclntosh, G.; Thaut, M. How Music Helps to Heal the Injured Brain: Therapeutic Use Crescendos Thanks to Advances in Brain Science. The Dana Foundation. 2010. Available online: http://www.dana.org/Cerebrum/Default.aspx?id=39437 (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Ling, Z.; Huang, J.; Hong, B.; Wang, X. Neural Correlates of Music Listening and Recall in the Human Brain. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 8112–8123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelsch, S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelsch, S. A coordinate-based meta-analysis of music-evoked emotions. NeuroImage 2020, 223, 117350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, H.E. Music-Evoked Emotions-Current Studies. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S. Emotion and Music. In The Cambridge Handbook of Human Affective Neuroscience; Armony, J., Vuilleumier, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, H.; Toyoshima, K. Music facilitates the neurogenesis, regeneration, and repair of neurons. Med. Hypothes. 2008, 71, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

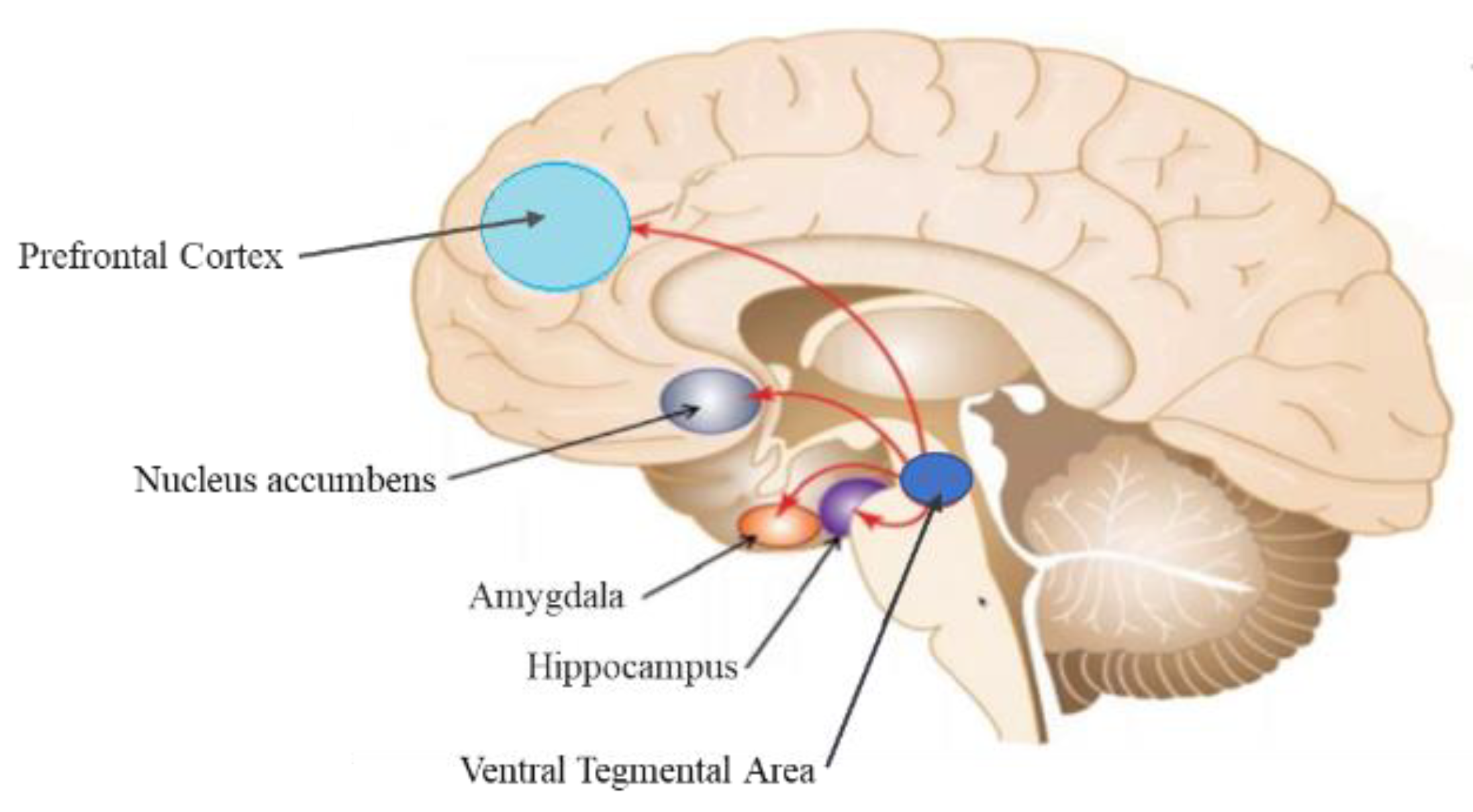

- Mavridis, I.N. Music and the nucleus accumbens. Surg. Radiol. Anat. SRA 2015, 37, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J. Musical pleasure and reward: Mechanisms and dysfunction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1337, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R. Drug Addiction. 2019. Available online: https://drrajivdesaimd.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/brain-and-drug-2.jpg (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Koelsch, S. Towards a neural basis of music-evoked emotions. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S.; Skouras, S.; Fritz, T.; Herrera, P.; Bonhage, C.; Küssner, M.B.; Jacobs, A.M. The roles of superficial amygdala and auditory cortex in music-evoked fear and joy. NeuroImage 2013, 81, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armony, J.L.; Aubé, W.; Angulo-Perkins, A.; Peretz, I.; Concha, L. The specificity of neural responses to music and their relation to voice processing: An fMRI-adaptation study. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 593, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reybrouck, M.; Vuust, P.; Brattico, E. Music and brain plasticity: How sounds trigger neurogenerative adaptations. Neuroplast. Insights Neural Reorganization 2018, 85, 74318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groussard, M.; Viader, F.; Landeau, B.; Desgranges, B.; Eustache, F.; Platel, H. The effects of musical practice on structural plasticity: The dynamics of grey matter changes. Brain Cogn. 2014, 90, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszewska, A.M.; Gaca, M.; Herman, A.M.; Jednoróg, K.; Marchewka, A. How Musical Training Shapes the Adult Brain: Predispositions and Neuroplasticity. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 630829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, P.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Xie, Y.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, S. Structural Covariance Changes of Anterior and Posterior Hippocampus During Musical Training in Young Adults. Front. Neuroanat. 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelsch, S.; Skouras, S. Functional centrality of amygdala, striatum, and hypothalamus in a “small-world” network underlying joy: An fMRI study with music. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014, 35, 3485–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, S.; Fancourt, D. The biological impact of listening to music in clinical and nonclinical settings: A systematic review. Prog. Brain Res. 2018, 237, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.H.; Kitsis, M.; Golovyan, D.; Wang, S.; Chlan, L.L.; Boustani, M.; Khan, B.A. Effects of music intervention on inflammatory markers in critically ill and post-operative patients: A systematic review of the literature. Heart Lung J. Crit. Care 2018, 47, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S.; Fuermetz, J.; Sack, U.; Bauer, K.; Hohenadel, M.; Wiegel, M.; Kaisers, U.X.; Heinke, W. Effects of Music Listening on Cortisol Levels and Propofol Consumption during Spinal Anesthesia. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinger, O.S.; Gooding, L.F. A systematic review of music-based interventions for procedural support. J. Music Ther. 2015, 52, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.A.; Emard, N.; Liou, K.T.; Popkin, K.; Borten, M.; Nwodim, O.; Atkinson, T.M.; Mao, J.J. Patient Perspectives on Active vs. Passive Music Therapy for Cancer in the Inpatient Setting: A Qualitative Analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakka, L.S.; Saarikallio, S. Spontaneous Music-Evoked Autobiographical Memories in Individuals Experiencing Depression. Music Sci. 2020, 3, 2059204320960575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiderscheit, A.; Breckenridge, S.J.; Chlan, L.L.; Savik, K. Music preferences of mechanically ventilated patients participating in a randomized controlled trial. Music Med. 2014, 6, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradt, J.; Dileo, C. Music interventions for mechanically ventilated patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD006902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parada-Cabaleiro, E.; Batliner, A.; Schedl, M. An Exploratory Study on the Acoustic Musical Properties to Decrease Self-Perceived Anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Yowler, C.J.; Super, D.M.; Fratianne, R.B. The interplay of preference, familiarity and psychophysical properties in defining relaxation music. J. Music Ther. 2012, 49, 150–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.S. A systematic review on the neural effects of music on emotion regulation: Implications for music therapy practice. J. Music Ther. 2013, 50, 198–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, P. The Stress of This Moment Might Be Hurting Kids’ Development. 2021. Available online: https://turnaroundusa.org/pamela-cantor-m-d-pens-guest-post-for-education-next/ (accessed on 13 November 2021).

| Authors, Date | Imaging Techniques | Brain Measurements |

|---|---|---|

| Boccia et. al., 2016 | Functional magnetic resonance imaging OR positron emission tomography | Structural brain changes related to PTSD symptomatology Functional connectivity of a brain region |

| Etkin & Wager, 2007 | Functional magnetic resonance imaging OR positron emission tomography | Functional activity of a brain region |

| Coburn et. al., 2018 | Structural magnetic resonance imaging | Structural brain changes |

| McNerney et. al., 2018 | Neuroimaging | Structural brain scan |

| Postel et. al., 2021 | High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging | Structural changes in hippocampal subfields |

| Gilbertson et. al., 2002 | Structural magnetic resonance imaging | Image acquisition and volumetric analyses of hippocampus |

| Smith et. al., 2005 | Magnetic resonance images | Hippocampal volume |

| van Rooij et. al., 2015 | Magnetic resonance imaging | Hippocampal volume |

| Wang et al., 2010 | High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging | Volumes of hippocampal subfields |

| Grupe et al., 2019 | Structural magnetic resonance imaging | Volume of the hippocampus and amygdala |

| Selemon et. al., 2019 | Functional magnetic resonance imaging | Structural and functional changes in brain |

| Stevens et. al., 2013 | Functional magnetic resonance imaging | Functional activity of amygdala and prefrontal cortex Amygdala-prefrontal cortex connectivity |

| Liu et. al., 2021 | 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging | Functional connectivity of the amygdala and its subregions |

| Delgado et. al., 2008 | Functional magnetic resonance imaging | Functional connectivity and emotional regulation |

| Johnstone et. al., 2007 | Functional magnetic resonance imaging | Functional activity of amygdala and prefrontal cortex |

| Urry et. al., 2006 | Functional magnetic resonance imaging | Brain activity in ventral lateral, dorsolateral, and dorsomedial regions of PFC and amygdala |

| Xiong et. al., 2013 | Event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging | Activity in the inferior frontal cortex, inferior parietal lobule, insula and putamen, posterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala in responses to negative stimuli |

| Matsuo et. al., 2003 | Near-infrared spectroscopy | Hemodynamic response of the prefrontal cortex during a cognitive task |

| Mary et al., 2020 | Functional magnetic resonance imaging | Mechanisms of memory suppression after trauma |

| Brain Areas | Neurobiological Changes | Effects on Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus | Reduced volume and activity, reduced dendritic spines and branches of pyramidal neurons in CA3, and Inhibited neurogenesis | Exaggerated activation and inability to terminate stress response, impaired extinction of fear conditioning, non-discrimination between safe/unsafe stimuli, and repressed memories |

| Amygdala | Increased reactivity, and altered communication with other brain regions | Promotes hypervigilance and impairs discrimination of threat |

| Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) | Reduced volume and activity, and disrupted communication with amygdalae | Decreased reactivity of PFC to exert inhibitory control over stress responses and dysfunctional thought process and decision making |

| Author (s), Year | Study Design | Type of Effect | Measure of Effect | Interpretation of Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al., 2018 | Systematic Review of 7 interventional studies | Decrease in severity of PTSD | Effect sizes ranged from low-medium effect (PTSD measures used: IES-R and PTSD-8) | Significant reduction in symptoms of PTSD when there was ongoing therapist involvement compared to when there was little therapist or no therapist involvement. |

| Story & Beck, 2017 | Mixed methods | Improved coping Improved emotional regulation Decrease in severity of PTSD | Change in PTSD symptoms, ES = 1.0 | Participants reported experiencing music as a tool for coping with PTSD symptoms, regulating emotions, decreasing arousal, expressing repressed feelings, and connecting with others. |

| Pourmovahed et al., 2021 | Randomized control trial | Improved emotional regulation Decrease in severity of PTSD Decreased anxiety levels | Severity of the PTSD decreased significantly after the intervention in the experimental group (F 1, 57 = 1046, p = 0.003) Difference between the two groups (F1, 07 = 1058, p < 0.03) confirmed significant effect of the non-verbal music on decreasing the PTSD severity | Listening to non-verbal music reduced severity of PTSD and the mother’s stress consequently promoting emotional bonding between the mother and baby. |

| Bensimon et al., 2008 | Mixed method | Improved emotional regulation Decreased anxiety levels | Reducing the client’s self-reported anxiety during confrontation with feared stimuli Effect measures not reported | Coping with difficulties such as feelings of loneliness, harsh traumatic memories, outbursts of anger, and loss of control. |

| Carr et al., 2012 | Mixed method study | Decrease in severity of PTSD Decrease in depression | IES-R significant reduction from baseline of (−17.20; 95% CI: [−24.94, −9.45; p = 0.0012]) Reduction in BDI-II symptom severity (−0.71) | Music and guided imagery can improve symptoms of Complex PTSD and dissociation, alleviate interpersonal problems, and enhance factors that promote health. |

| Rudstam et al., 2017 | Mixed method study | Decrease in severity of PTSD Decrease in depression Decreased anxiety levels Decreased dissociation symptoms Improved quality of life | Pre-post Comparisons

| Significant decreases in PTSD symptoms with very large effect sizes, and dissociation with large effect sizes, and an increase in quality of life with small to medium effect size. Music helped establish contact with feelings and body sensations and provided an experience of expansion, relaxation, and new energy. |

| Maack, 2012 | Mixed method study | Decrease in severity of PTSD Decreased dissociation symptoms Improved quality of life | Kruskal–Wallis-Test shows that there was a significant difference in change of severity of symptoms between the groups (p < 0.001). KW test statistic not reported. Mann–Whitney Tests shows that there was a significant difference in change of severity of symptoms between the GIM and the control group (U = 1.50, p < 0.001). | The symptoms of the participants of the GIM group improved significantly more than the symptoms of the participants of the PITT group. |

| Beck et al., 2017 | Pre- post-test study | Decrease in severity of PTSD Improved quality of life | Pre-post Comparisons

| Significant changes in positive directions on all four outcome measures, PTSD symptoms, sleep quality, well-being, and social functioning. |

| Macfarlane et al., 2019 | Pre- post-test study | Decrease in severity of PTSD | Average reduction of PTSD symptoms of 38% between the entrance screening and the final point of the intervention, using PSS-I | A drop of ten points or more on PSS-I score for eight of the participants, among which five had a final scored below PTSD threshold. Applicable in a complex clinical setting with a very mixed and treatment resistant population, who were not eligible for EMDR or another type of trauma treatment, at the moment of enrollment. |

| Blanaru et al., 2012 | Mixed method study | Decrease in depression | Significant reduction in BDI score for depression following music relaxation compared with baseline [F (1,11) = 14.8, p< 0.003] | Music relaxation was found to be effective and led to significant improvements in sleep measures and significant reduction of depression score in PTSD patients. |

| Beck et al., 2021 | Randomized control trial | Decreased dissociation symptoms Improved quality of life | Music group well-being, large effect size

| Small to large effect sizes in both psychological treatment group and music therapy group, with significant medium effect sizes, for well-being and psychoform dissociation at follow-up. A high dropout rate of 40% occurred in the psychological treatment group, compared to 5% in the music therapy group. |

| Zergani & Naderi, 2016 | Randomized control trial | Decreased anxiety levels Improved quality of life | Significant difference between experiment and control groups for anxiety symptoms (F-13.67; p < 0.0001), STAI scale, and quality of life (F-26.99; p < 0.0001), SF-36 scale | The effect of music remained stable even after one month of follow-up. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pant, U.; Frishkopf, M.; Park, T.; Norris, C.M.; Papathanassoglou, E. A Neurobiological Framework for the Therapeutic Potential of Music and Sound Interventions for Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Critical Illness Survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053113

Pant U, Frishkopf M, Park T, Norris CM, Papathanassoglou E. A Neurobiological Framework for the Therapeutic Potential of Music and Sound Interventions for Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Critical Illness Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053113

Chicago/Turabian StylePant, Usha, Michael Frishkopf, Tanya Park, Colleen M. Norris, and Elizabeth Papathanassoglou. 2022. "A Neurobiological Framework for the Therapeutic Potential of Music and Sound Interventions for Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Critical Illness Survivors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053113

APA StylePant, U., Frishkopf, M., Park, T., Norris, C. M., & Papathanassoglou, E. (2022). A Neurobiological Framework for the Therapeutic Potential of Music and Sound Interventions for Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Critical Illness Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053113