The Provider Role and Perspective in the Denial of Family Planning Services to Women in Malawi: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Design and Study Aim

2.2. Sites

2.3. Setting

2.4. Study Sample and Data Collection

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

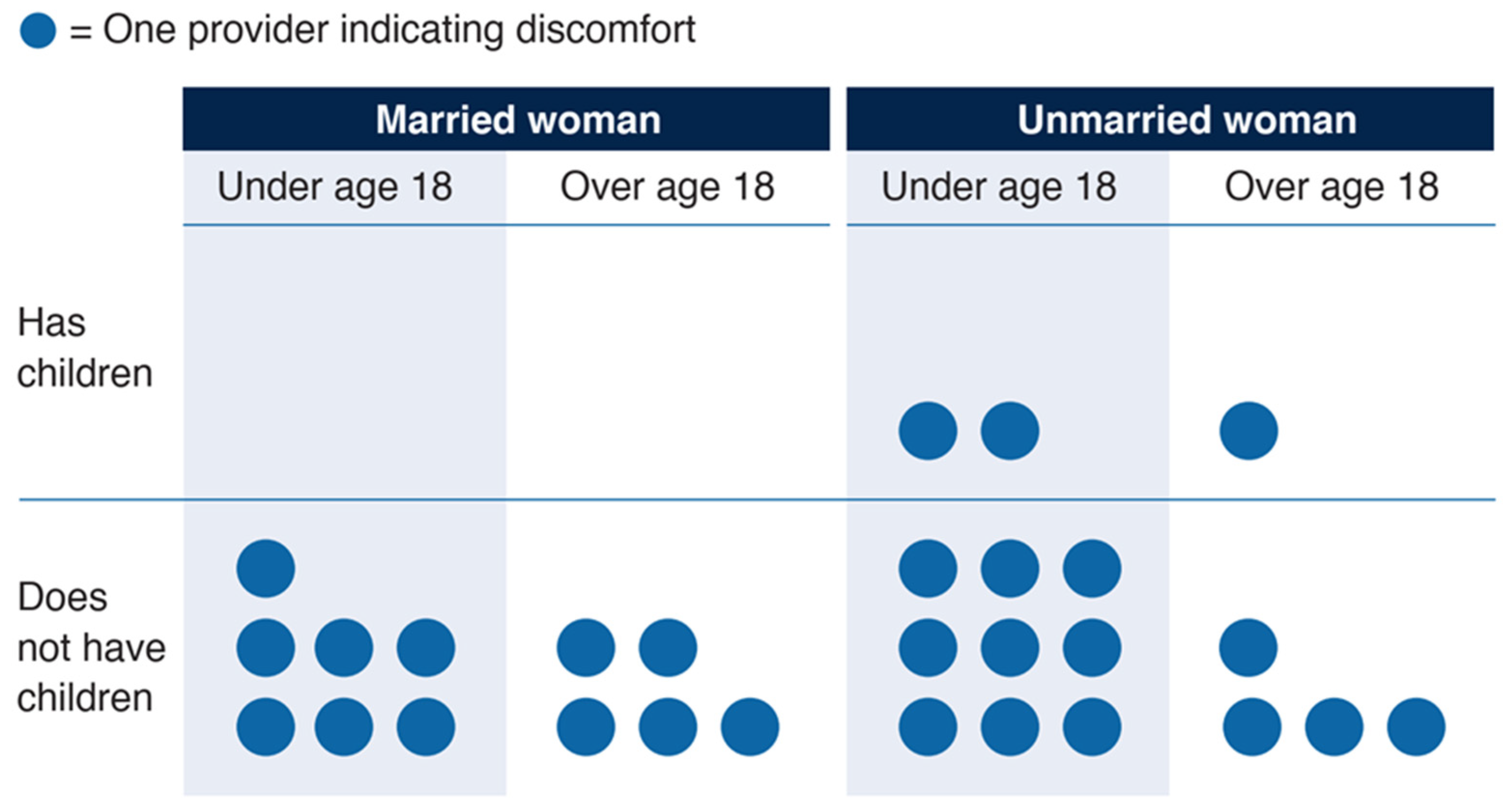

3.1. Provider Survey

3.1.1. Requirements for Clients Initiating Various Methods

3.1.2. Reasons Providers Were Uncomfortable Providing Certain Clients with Services

3.2. Provider In-Depth Interviews

3.2.1. Client Types Providers Are Uncomfortable Initiating on Family Planning

As for me, teenagers are very hard for me to provide the method most of the time. I still feel they may not concentrate on school or what they’re doing. Some of them are very young like 14; some of them are as young as 13. So it’s very hard for me to provide the methods to them though I still provide. Most of the health workers there, we even ask each other, should I still provide? None of us are comfortable providing to teenagers because we just become afraid, I don’t know why. Sometimes we are afraid that maybe they might have uterine fibroids, and sometimes we are afraid that they may not continue school and not concentrate.

Personally, it’s not been medically proven but most of us just worry that they might have problems when they get married and want a baby. Fertility might not return as quick as we think, or most of us are afraid that maybe because they protect themselves against pregnancy, but are they protecting themselves against the STIs?

Sometimes I am uncomfortable to provide permanent methods to the indecisive ladies. If she says I haven’t really talked to my husband, then I tell her to go back so she can discuss it with her husband.

3.2.2. Reasons for Turnaway

Because of myths we find a lot of women who are already maybe one month pregnant, but most think that if we give them a method they will abort. That’s why after one or two months you see a good number of women who come wanting to be put on Implanon, but after assessing you find that they are pregnant. And they are open, they tell you that I thought that if you put Implanon in me the pregnancy will go away.

…for some, they would say they are suspecting themselves to be pregnant so we offer them [a pregnancy test] to rule out pregnancy, and sometimes when they are saying that they are having menses we would even see, because some can cheat to say that they are having menses just to get a method, which is not good for them.

And mainly they come back to say that your methods are not working, that’s why I’m pregnant, so we have to make sure that sometimes they’re not pregnant and then we give a method.

…especially implants the women cannot hide it because someone can see it, so if the husband realizes that the wife has a family planning method it brings conflicts to the family, which will force the woman to come seek for removal when the days are not due.

3.2.3. Provider Reports of Community-Held Beliefs and Myths about Family Planning

- Only women with children (or a certain number) should use FP.

- Using FP reduces a woman’s sex drive.

- Young people should not use FP; they might be ridiculed and called prostitutes if they are known to be using FP.

- Initiating a method can induce an abortion.

- Implants and IUDs can cause pain to men during intercourse.

- FP causes the uterus to swell.

- Implants can migrate to the heart or stomach.

- FP methods used by women can cause impotency in men.

- OCPs can accumulate in the stomach.

- In the community, there is a preference for methods provided by the witch doctor.

- If a woman initiates soon after delivering a child, she might be promiscuous as local custom says sexual relations should not re-start for 6 months.

- FP can cause sterility.

3.2.4. Areas for Service Improvement

The misconceptions and the myths, they are still circulating in the villages. If somebody sees a side effect of a certain family planning method, she may choose to discourage friends who want to take the same method. You may see a lot of women who have been told by their friends about side effects hence discouraging them to take the method which are we are encouraging women to take. One example is Jadelle. One year you will see a woman has come who has taken Jadelle, and next year she is coming and saying it is doing me such bad things in my body. When you ask, you see that she has just gotten the message from a friend it will kill you, so that’s our major challenge. We may waste a lot of Jadelles because of these myths and misconceptions.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Program of Action of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (Chapters I-VIII). Popul. Dev. Rev. 1995, 21, 187–213. [CrossRef]

- Starrs, A.M.; Ezeh, A.C.; Barker, G.; Basu, A.; Bertrand, J.T.; Blum, R.; Coll-Seck, A.M.; Grover, A.; Laski, L.; Roa, M.; et al. Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: Report of the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission. Lancet 2018, 391, 2642–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Sahin-Hodoglugil, N.N.; Potts, M. Barriers to fertility regulation: A review of the literature. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2006, 37, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, J.T.; Hardee, K.; Magnani, R.J.; Angle, M.A. Access, auality of care and medical barriers in family planning programs. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 1995, 21, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.M.; Bendabenda, J.; Mboma, A.; Gunnlaugsson, G.; Stanback, J.; Chen, M. Turned Away and at Risk: Denial of Family Planning Services to Women in Malawi. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2022, Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Stanback, J.; Thompson, A.; Hardee, K.; Janowitz, B. Menstruation requirements: A significant barrier to contraceptive access in developing countries. Stud. Fam. Plan. 1997, 28, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunie, A.; Tolley, E.E.; Ngabo, F.; Wesson, J.; Chen, M. Getting to 70%: Barriers to modern contraceptive use for women in Rwanda. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 123, e11–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumlinson, K.; Okigbo, C.C.; Speizer, I.S. Provider barriers to family planning access in urban Kenya. Contraception 2015, 92, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanback, J.; Twum-Baah, K.A. Why do family planning providers restrict access to services? An examination in Ghana. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 2001, 27, 37–41. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/article_files/2703701.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tavrow, P.; Namate, D.; Mpemba, N. Quality of Care: An Assessment of Family Planning Providers’ Attitudes and Client-Provider Interactions in Malawi; Center of Social Research, University of Malawi: Zomba, Malawi, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Solo, J.; Festin, M. Provider Bias in Family Planning Services: A Review of its Meaning and Manifestations. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2019, 7, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malawi National Statistics Office. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–2016; National Statistics Office (NSO) [Malawi]: Zomba, Malawi; ICF: Rockville, MD, USA, 2017.

- Government of Malawi. Malawi Costed Implementation Plan for Family Planning, 2016–2020; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2015.

- Polis, C.B.; Mhango, C.; Philbin, J.; Chimwaza, W.; Chipeta, E.; Msusa, A. Incidence of induced abortion in Malawi, 2015. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Malawi, Ministry of Health. Preservice Education Family Planning Reference Guide; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2010.

- FHI 360. Malawi: Monitoring and Evaluation of Community-Based Access to Injectable Contraception; FHI 360: Durham, NC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/malawi-injectable-contraceptives.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2020).

- Government of Malawi, Ministry of Health. National Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) Policy 2017–2022; United Nations Population Fund: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2017. Available online: https://malawi.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/Malawi_National_SRHR_Policy_2017-2022_16Nov17.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- United Nations. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 28 January 2019).

- Biggs, M.A.; Upadhyay, U.D.; McCulloch, C.E.; Foster, D.G. Women’s Mental Health and Well-being 5 Years After Receiving or Being Denied an Abortion: A Prospective, Longitudinal Cohort Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavrakas, P.J. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 1-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, C.; Lerer, A.; Anokwa, Y.; Tseng, C.; Brunette, W.; Borriello, G. Open data kit: Tools to build information services for developing regions. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, London, UK, 13–16 December 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo (Version 12). 2018. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavrow, P. What Prevents Family Planning Clinics in Developing Countries from Adoptiong a Client Orientation? An Exploratory Study from Malawi; University of Malawi’s Center for Social Research: Zomba, Malawi, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hazel, E.; Mohan, D.; Chirwa, E.; Phiri, M.; Kachale, F.; Msukwa, P.; Katz, J.; Marx, M.A. Disrespectful care in family planning services among youth and adult simulated clients in public sector facilities in Malawi. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, K.; O’Malley, G.; Geoffroy, E.; Schell, E.; Bvumbwe, A.; Denno, D.M. “Our girls need to see a path to the future”--perspectives on sexual and reproductive health information among adolescent girls, guardians, and initiation counselors in Mulanje district, Malawi. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, M.R.; Phiri, K.; Parent, J.; Phoya, A.; Schooley, A.; Hoffman, R.M. Provider perspectives on barriers to reproductive health services for HIV-infected clients in Central Malawi. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Med. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bornstein, M.; Huber-Krum, S.; Kaloga, M.; Norris, A. Messages around contraceptive use and implications in rural Malawi. Cult. Health Sex. 2021, 23, 1126–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlough, M.; Jacobstein, R. Five Ways to Address Provider Bias in Family Planning. Available online: https://www.intrahealth.org/vital/five-ways-address-provider-bias-family-planning (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Rutenberg, N.; Watkins, S.C. The Buzz Outside the Clinics: Conversations and Contraception in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Stud. Fam. Plan. 1997, 28, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipeta, E.; Chimwaza, W.; Kalilani-Phiri, L. Contraceptive Knowledge, Beliefs and Attitudes in Rural Malawi: Misinformation, Misbeliefs and Misperceptions. Malawi Med. J. 2010, 22, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueye, A.; Speizer, I.S.; Corroon, M.; Okigbo, C.C. Belief in Family Planning Myths at the Individual and Community Levels and Modern Contraceptive Use in Urban Africa. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2015, 41, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesar, R.J.; Audibert, M.; Comfort, A.B. Cost-effectiveness analysis and mortality impact estimation of scaling-up pregnancy test kits in Madagascar, Ethiopia and Malawi. Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckmanns, T.; Bessert, J.; Behnke, M.; Gastmeier, P.; Ruden, H. Compliance with antiseptic hand rub use in intensive care units: The Hawthorne effect. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2006, 9, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total | Zomba | Machinga | Kasungu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 57 n (%) | N = 19 n (%) | N = 20 n (%) | N = 18 n (%) | |

| Responses | 57 (100) | 19 (33) | 20 (35) | 18 (32) |

| Facility Type | ||||

| Hospital * | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 1 (6) |

| Health center | 48 (84) | 15 (79) | 16 (80) | 17 (94) |

| Health post | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Dispensary | 4 (7) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| What is your professional cadre? | ||||

| Nurse | 30 (53) | 13 (68) | 10 (50) | 7 (39) |

| HSA | 14 (25) | 2 (11) | 8 (40) | 4 (22) |

| Clinician | 9 (16) | 3 (16) | 2 (10) | 4 (22) |

| Community midwife assistant | 3 (5) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) |

| Pharmacy clerk | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| How often are family planning services available at this facility? | ||||

| Daily | 21 (37) | 11 (58) | 8 (40) | 2 (11) |

| Weekly | 17 (30) | 2 (11) | 7 (35) | 8 (44) |

| More than once a week but not daily | 19 (33) | 6 (32) | 5 (25) | 8 (44) |

| On the days you provide family planning services, how many clients do you personally see on average? | ||||

| 1 to 5 | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| 6 to 10 | 5 (9) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 3 (17) |

| More than 10 | 51 (89) | 18 (95) | 19 (95) | 14 (78) |

| How often is family planning group counseling offered? | ||||

| Group counseling not regularly offered | 6 (11) | 4 (21) | 1 (5) | 1 (6) |

| Daily | 27 (47) | 11 (58) | 8 (40) | 8 (44) |

| Weekly | 11 (19) | 2 (11) | 4 (20) | 5 (28) |

| More than once a week but not daily | 13 (23) | 2 (11) | 7 (35) | 4 (22) |

| On average, how many women attended each group counseling session? | ||||

| N = 51 | N = 15 | N = 19 | N = 17 | |

| 10 or fewer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 11 to 15 | 11 (22) | 8 (53) | 2 (11) | 1 (6) |

| More than 15 | 40 (78) | 7 (47) | 17 (90) | 16 (94) |

| Method | Method Normally Available at this Facility? N = 57 | Has a Method Normally Available Been Stocked out in the Past Week? |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Condoms | 57 (100) | 0 (0) |

| OCP *-combined | 57 (100) | 2 (4) |

| Injectable-IM | 54 (95) | 12 (23) |

| Implant-Jadelle | 53 (93) | 14 (27) |

| Implant-Implanon | 53 (93) | 5 (9) |

| OCP-Progesterone only | 51 (89) | 5 (10) |

| Emergency contraception | 34 (60) | 4 (12) |

| Injectable subcutaneous | 26 (46) | 1 (4) |

| IUD * | 19 (33) | 1 (5) |

| Tubal ligation | 11 (19) | 2 (18) |

| Vasectomy | 6 (11) | 2 (33) |

| OCP * | Injectable | Implant | IUD * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 57 | N = 57 | N = 53 | N = 19 | |

| What requirements do you have for women initiating the method specified? | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Medically eligible | 38 (67) | 40 (70) | 42 (87) | 18 (95) |

| Negative pregnancy test | 39 (68) | 38 (67) | 36 (68) | 13 (68) |

| Currently menstruating | 34 (60) | 34 (60) | 24 (45) | 9 (47) |

| Reasonably sure not pregnant | 18 (32) | 20 (35) | 14 (26) | 4 (21) |

| Negative pregnancy test if not currently menstruating | 11 (19) | 14 (25) | 13 (25) | 4 (21) |

| HIV test | 12 (21) | 16 (28) | 20 (38) | 7 (36) |

| Pelvic exam | 6 (11) | 5 (9) | 5 (9) | 6 (32) |

| Already has children | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 1 (5) |

| Spousal consent | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Parental consent if under 18 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Immunization | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| None | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peterson, J.M.; Bendabenda, J.; Mboma, A.; Chen, M.; Stanback, J.; Gunnlaugsson, G. The Provider Role and Perspective in the Denial of Family Planning Services to Women in Malawi: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3076. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053076

Peterson JM, Bendabenda J, Mboma A, Chen M, Stanback J, Gunnlaugsson G. The Provider Role and Perspective in the Denial of Family Planning Services to Women in Malawi: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):3076. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053076

Chicago/Turabian StylePeterson, Jill M., Jaden Bendabenda, Alexander Mboma, Mario Chen, John Stanback, and Geir Gunnlaugsson. 2022. "The Provider Role and Perspective in the Denial of Family Planning Services to Women in Malawi: A Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 3076. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053076

APA StylePeterson, J. M., Bendabenda, J., Mboma, A., Chen, M., Stanback, J., & Gunnlaugsson, G. (2022). The Provider Role and Perspective in the Denial of Family Planning Services to Women in Malawi: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 3076. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053076