(Not That) Essential: A Scoping Review of Migrant Workers’ Access to Health Services and Social Protection during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Immigration Policies in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand

1.2. COVID-19-Related Policies in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand

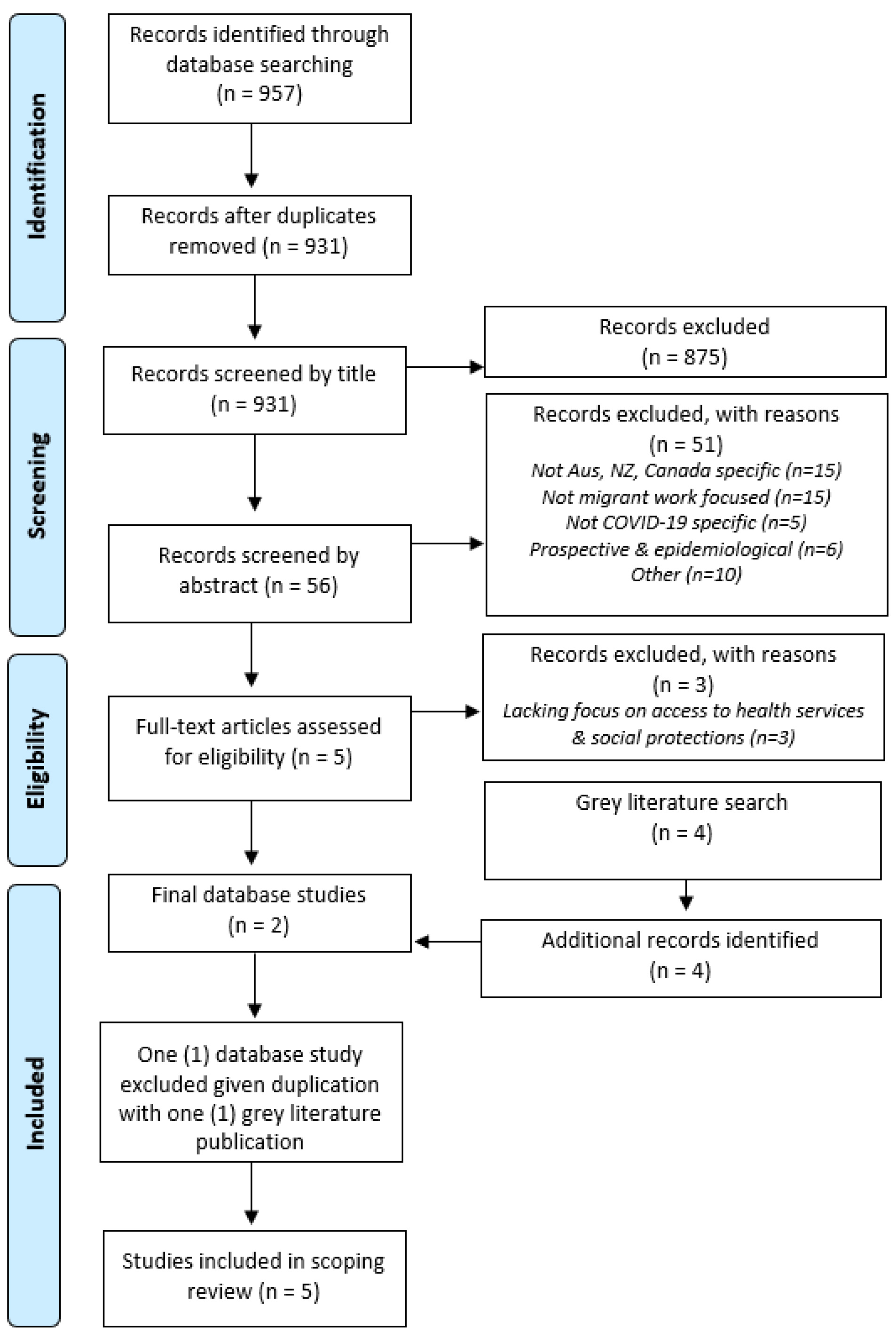

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database Search Strategy

2.2. Grey Literature Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of Included Migrant Workers

3.2. Immigration Status of Included Migrant Workers and Their Employment Sectors

3.3. Access to Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.4. Access to Social Protection during the COVID-19 Pandemic

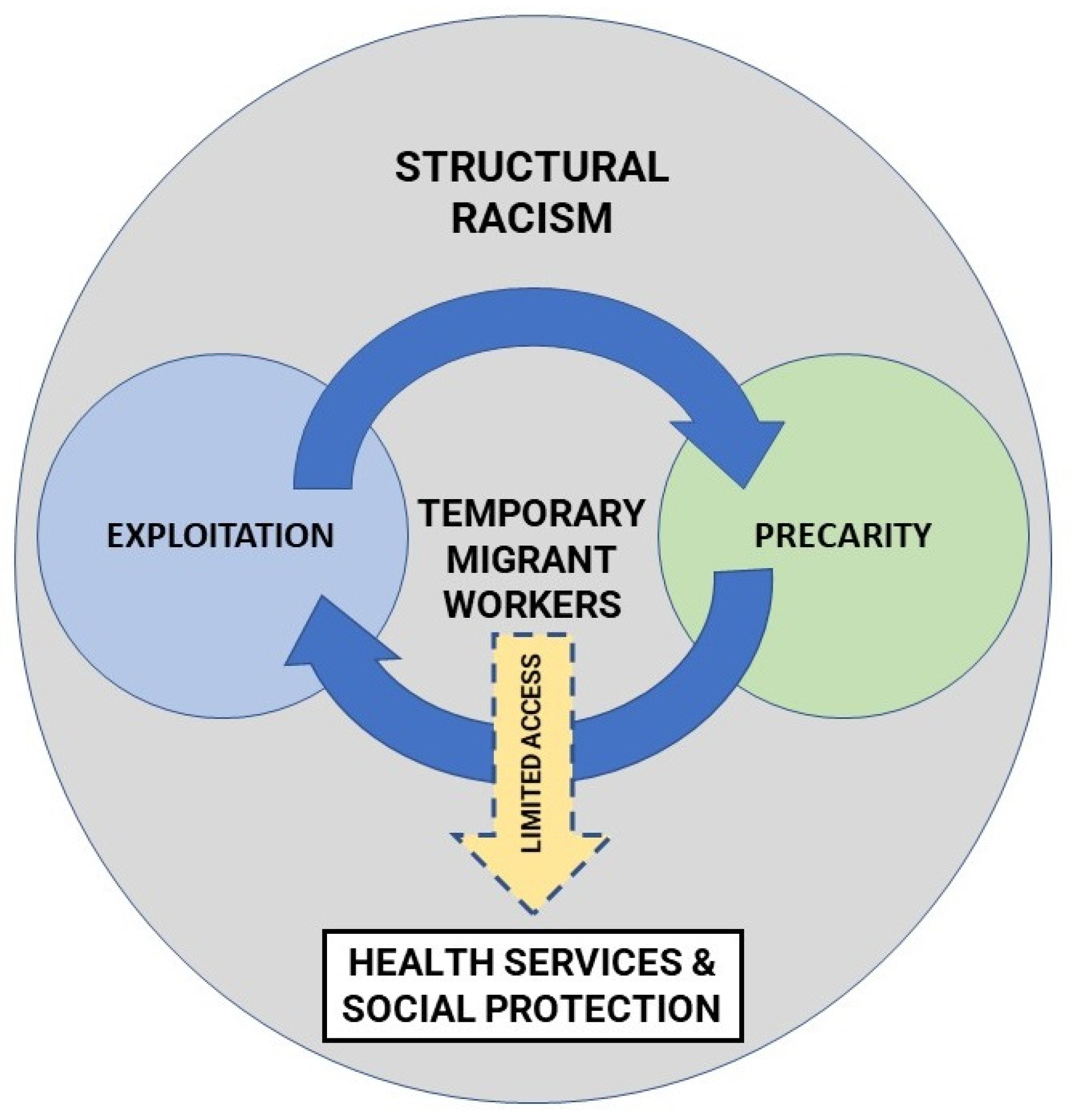

3.5. Racism

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Labour Organization. ILO Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers: Results and Methodology. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_652001.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Hayward, S.E.; Deal, A.; Cheng, C.; Crawshaw, A.; Orcutt, M.; Vandrevala, T.F.; Norredam, M.; Carballo, M.; Ciftci, Y.; Requena-Méndez, A.; et al. Clinical outcomes and risk factors for COVID-19 among migrant populations in high-income countries: A systematic review. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, A.N.; Peleteiro, B.; Martins, M.D.R.O. The Writing’s on the Wall: On Health Inequalities, Migrants, and Coronavirus. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenaway, C.; Hargreaves, S.; Barkati, S.; Coyle, C.M.; Gobbi, F.; Veizis, A.; Douglas, P. COVID-19: Exposing and addressing health disparities among ethnic minorities and migrants. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hintermeier, M.; Gencer, H.; Kajikhina, K.; Rohleder, S.; Hövener, C.; Tallarek, M.; Spallek, J.; Bozorgmehr, K. SARS-CoV-2 among migrants and forcibly displaced populations: A rapid systematic review. J. Migr. Health 2021, 4, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization. Protecting Migrant Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Recommendations for Policy-Makers and Constituents. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labour-migration/publications/WCMS_743268/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Kumar, C.; Oommen, E.; Fragapane, F.; Foresti, M. Working Paper 605. Beyond Gratitude: Lessons Learned from Migrants Contribution to the COVID-19 Response. Available online: https://odi.org/en/publications/beyond-gratitude-lessons-learned-from-migrants-contribution-to-the-covid-19-response/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. COVID-19 and Key Workers: What Role do Migrants Play in Your Region? Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=556_556459-ypjayidpkt&title=COVID-19-and-key-workers-What-role-do-migrants-play-in-your-region&_ga=2.74949649.244811173.1630124853-976243609.1630124853 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Landry, V.; Semsar-Kazerooni, K.; Tjong, J.; Alj, A.; Darnley, A.; Lipp, R.; Guberman, G.I. The systemized exploitation of temporary migrant agricultural workers in Canada: Exacerbation of health vulnerabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic and recommendations for the future. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, A.; Wang, C.; Wariyanti, Y.; Latkin, C.A.; Hall, B. The neglected health of international migrant workers in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.; Rhonda-Perez, E.; Schenker, M.B. Migrant workers, essential work, and COVID-19. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuyisenge, G.; Goldenberg, S.M. COVID-19, structural racism, and migrant health in Canada. Lancet 2021, 397, 650–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, H.; Holmes, S.M.; Madrigal, D.S.; Young, M.-E.D.; Beyeler, N.; Quesada, J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramage, K.; Vearey, J.; Zwi, A.B.; Robinson, C.; Knipper, M. Migration and health: A global public health research priority. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Evidence Review on Health and Migration. Refugees and Migrants in Times of COVID-19: Mapping Trends of Public Health and Migration Policies and Practices. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240028906 (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Giuntella, O.; Kone, Z.; Ruiz, I.; Vargas-Silva, C. Reason for immigration and immigrants’ health. Public Health 2018, 158, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.; Rodriguez, D.X.; McDaniel, P.N. Immigration status as a health care barrier in the USA during COVID-19. J. Migr. Health 2021, 4, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauvergne, C. Settler societies and the immigration imagination. In The New Politics of Immigration and the End of Settler Societies; Dauvergne, C., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 10–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ongley, P.; Pearson, D. Post-1945 international migration: New Zealand, Australia and Canada compared. Int. Migr. Rev. 1995, 29, 765–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, A.H.; Macdonald, M. Immigration policy in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: An overview of recent trends. Int. Migr. Rev. 2014, 48, 801–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, L. A Comparison of Skilled Migration Policy: Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2808881 (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Berg, L.; Farbenblum, B. As If We Weren’t Humans: The Abandonment of Temporary Migrants in Australia during COVID-19. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-09/apo-nid308305.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Underhill, E.; Rimmer, M. Layered vulnerability: Temporary migrants in Australian horticulture. J. Ind. Relat. 2016, 58, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.F. Why Do States Adopt Liberal Immigration Policies? The policymaking dynamics of skilled visa reform in Australia. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2015, 41, 306–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immigration New Zealand. Bringing Workers to New Zealand. Available online: https://www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/covid-19/covid-19-information-for-employers/bringing-workers-to-nz (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Business Queensland. Requirements for Pacific Labour Cheme and Seasonal Worker Programme. Available online: https://www.business.qld.gov.au/industries/farms-fishing-forestry/agriculture/coronavirus-support/requirements-workers/pacific-labour-seasonal-worker (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Australian Government Department of Home Affairs. Temporary Activity Visa (Subclass 408). Australian Government Endorsed Events (COVID-19 Pandemic Event). Available online: https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/visas/getting-a-visa/visa-listing/temporary-activity-408/australian-government-endorsed-events-covid-19 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Migrant Workers and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca8559en/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Australian Government Department of Health. The Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities COVID-19 Health Advisory Group. Terms of Reference. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/06/culturally-and-linguistically-diverse-communities-covid-19-health-advisory-group-terms-of-reference.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Immigration New Zealand. Newcomer Skills Matching Services Now Extended to Those that Have Lost Jobs. Available online: https://www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/media-centre/news-notifications/newcomer-skills-matching-services-extended (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Education New Zealand. Emergency Benefit for Temporary Visa Holders. Available online: https://enz.govt.nz/news-and-research/emergency-benefit-for-temporary-visa-holders/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Government of Canada. Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/subsidy/emergency-wage-subsidy.html (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Employment New Zealand. Previous Financial Support Schemes. Previous Financial Support Schemes for Business, Employers, and Employees. Available online: https://www.employment.govt.nz/leave-and-holidays/other-types-of-leave/coronavirus-workplace/previous-financial-support-schemes/ (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Employment and Social Development Canada. Government of Canada Invests in Measures to Boost Protections for Temporary Foreign Workers and Address COVID-19 Outbreaks on Farms. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2020/07/government-of-canada-invests-in-measures-to-boost-protections-for-temporary-foreign-workers-and-address-covid-19-outbreaks-on-farms.html (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Mema, S.; Frosst, G.; Hanson, K.; Yates, C.; Anderson, A.; Jacobson, J.; Guinard, C.; Lima, A.; Andersen, T.; Roe, M. COVID-19 outbreak among temporary foreign workers in British Columbia, March to May 2020. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2021, 47, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Temporary Public Policy to Facilitate the Granting of Permanent Residence for Foreign Nationals in Canada, Outside of Quebec, with Recent Canadian Work Experience in Essential Occupations. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/mandate/policies-operational-instructions-agreements/public-policies/trpr-canadian-work-experience.html (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Arora, A. Permanent Residency Pathway for Selected Skilled Migrants Who Chose to Say in Australia during COVID. Available online: https://www.sbs.com.au/language/english/permanent-residency-pathway-for-select-skilled-migrants-who-chose-to-stay-in-australia-during-covid (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caxaj, C.S.; Cohen, A. Relentless border walls: Challenges of providing services and supports to migrant agricultural workers in British Columbia. Can. Ethn. Stud. 2021, 53, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farbenblum, B.; Berg, L. “We might not be citizens but we are still people”: Australia’s disregard for the human rights of international students during COVID-19. Aust. J. Hum. Rights 2020, 26, 486–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migrant Workers Alliance for Change. Unheeded Warnings: COVID-19 and Migrant Workers in Canada. Available online: https://migrantworkersalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Unheeded-Warnings-COVID19-and-Migrant-Workers.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Belong Aotearoa. Migrant Experiences in the Time of COVID. Survey Report 2020. Available online: https://www.belong.org.nz/migrant-experiences-in-the-time-of-covid (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Atlin, J.; Loo, B.; Luo, N.; Mehboob, F.; Santos, M.; Schulmann, P. Impact of COVID-19 on the Economic Well-Being of Recent Migrants to Canada: A Report on Survey Results from Permanent Residents, Temporary Workers, and International Students in Canada. Available online: https://wenr.wes.org/2021/02/impact-of-covid-19-on-the-economic-well-being-of-recent-migrants-to-canada (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Benach, J.; Vives, A.; Amable, M.; Vanroelen, C.; Tarafa, G.; Muntaner, C. Precarious employment: Understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradies, Y.; Ben, J.; Denson, N.; Elias, A.; Priest, N.; Pieterse, A.; Gupta, A.; Kelaher, M.; Gee, G. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; Pocock, N.; Tan, S.T.; Pajin, L.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Wickramage, K.; McKee, M.; Pottie, K. Healthcare is not universal if undocumented migrants are excluded. BMJ 2019, 366, l4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, B. Health inequities faced by Ethiopian migrant domestic workers in Lebanon. Health Place 2018, 50, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migge, B.; Gilmartin, M. Migrants and healthcare: Investigating patient mobility among migrants in Ireland. Health Place 2011, 17, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bell, K.; Green, J. On the perils of invoking neoliberalism in public health critique. Crit. Public Health 2016, 26, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.J. COVID-19, Authoritarian neoliberalism, and precarious migrant work in Singapore: Structural violence and communicative inequality. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.J. Singapore’s extreme neoliberalism and the COVID outbreak: Culturally centering voices of low-wage migrant workers. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 65, 1302–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, B.; Juen, J.; Foster, J.; Okeke-Ihejirika, P.; Vallianatos, H.; Alaazi, D.; Piper, N.; Tull, M.; Daria, M.; Baca, M.; et al. Migration and Precarity: From the Temporary Foreign Worker Program to Undocumented Status. Policy Brief. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/nursing/media-library/research/migration-and-health/migration-and-precarity-policy-brief-final.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Yuval-Davis, N. The Politics of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goldade, K. “Health Is Hard Here” or “Health for All”? Med. Anthr. Q. 2009, 23, 483–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viruell-Fuentes, E.A.; Miranda, P.Y.; Abdulrahim, S. More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.; Vallianatos, H.; Green, J.; Obuekwe, C. Intersection of migration and access to health care: Experiences and perceptions of female economic migrants in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankivsky, O.; Kapilashrami, A. Beyond Sex and Gender Analysis: An Intersectional View of the COVID-19 Pandemic Outbreak and Response. Available online: https://mspgh.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/3334889/Policy-brief_v3.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. From Risk to Resilience: An Equity Approach to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19/cpho-covid-report-eng.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- De Haas, H.; Castles, S.; Miller, M.J. Categorisation of migration. In The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Search Terms | Records Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| Medline | COVID: COVID-19 or coronavirus or 2019-ncov or SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 Immigrant: Immigrant OR refugee OR migrant OR temporary resident Risk: risk OR vulnerable OR vulnerability Location: (Australia or Australian or Australians) OR (New Zealand or Aotearoa or NZ) OR (Canada or Canadian or Canadians) | 28 |

| PubMed | 28 | |

| Scopus | 901 | |

| Total | 957 | |

| Study | Country | Participant Demographics |

|---|---|---|

| Caxaj and Cohen [40] | Canada | 30 individuals in support roles for migrant farm workers in British Columbia. |

| Migrant Workers Alliance for Change [42] | Canada | 180 migrant farm workers who called a support hotline on behalf of 1162 workers. |

| Berg and Farbenblum [22] | Australia | 6105 temporary migrant workers 52% aged ≥ 25 71% from Asian countries 54% female 51% had stayed for ≥18 months |

| Belong Aotearoa [43] | New Zealand | 160 participants 81% aged ≥ 30 74% from Asian countries 69% female 51% arrived in the last 4 years 57% were temporary migrant workers |

| World Education Services [44] | Canada | 4932 participants 90% aged ≥ 25 45% from India 54% female 33% had stayed for ≥12 months 52% were temporary migrant workers |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Istiko, S.N.; Durham, J.; Elliott, L. (Not That) Essential: A Scoping Review of Migrant Workers’ Access to Health Services and Social Protection during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052981

Istiko SN, Durham J, Elliott L. (Not That) Essential: A Scoping Review of Migrant Workers’ Access to Health Services and Social Protection during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052981

Chicago/Turabian StyleIstiko, Satrio Nindyo, Jo Durham, and Lana Elliott. 2022. "(Not That) Essential: A Scoping Review of Migrant Workers’ Access to Health Services and Social Protection during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052981

APA StyleIstiko, S. N., Durham, J., & Elliott, L. (2022). (Not That) Essential: A Scoping Review of Migrant Workers’ Access to Health Services and Social Protection during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052981