Innovative Strategies to Fuel Organic Food Business Growth: A Qualitative Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

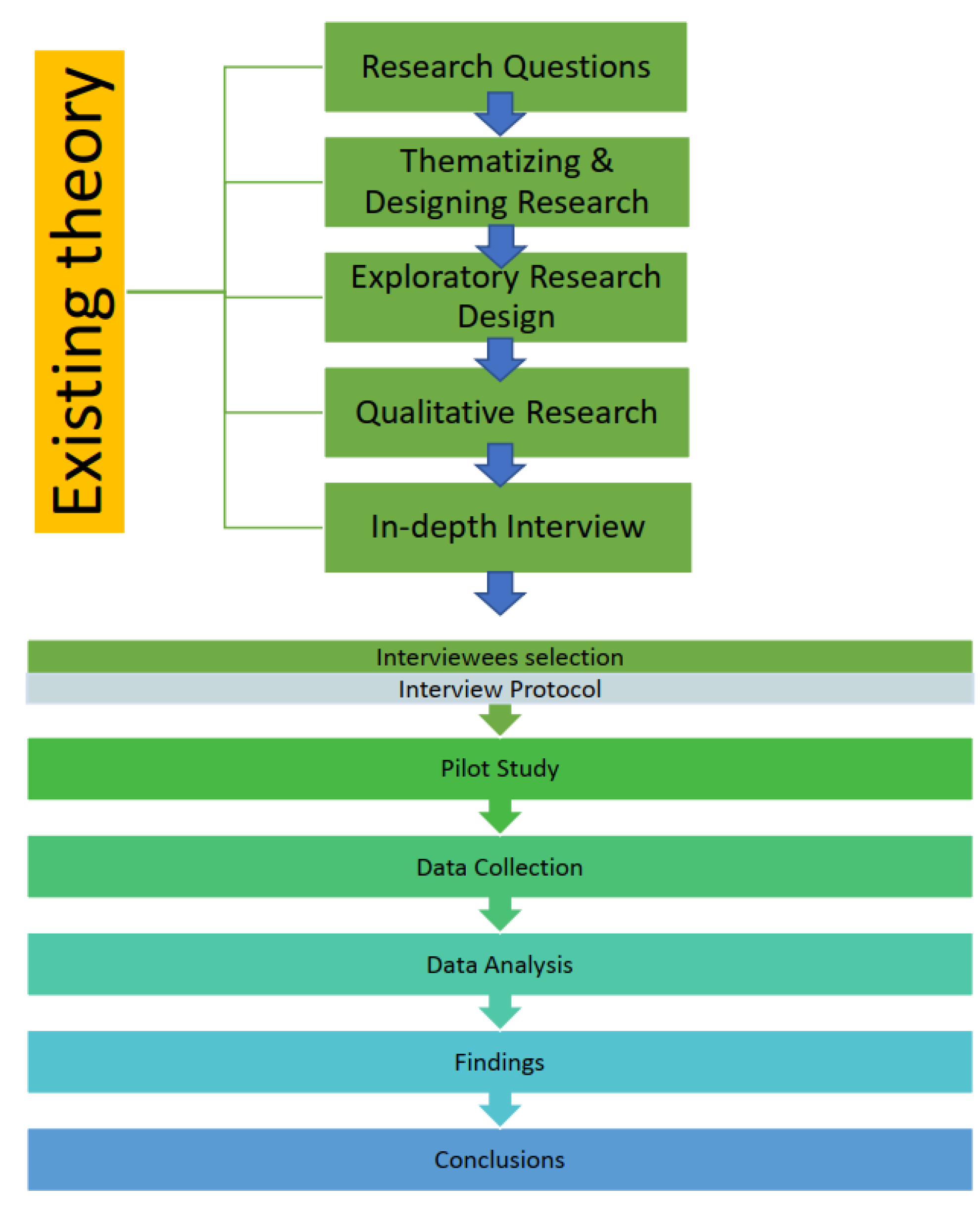

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

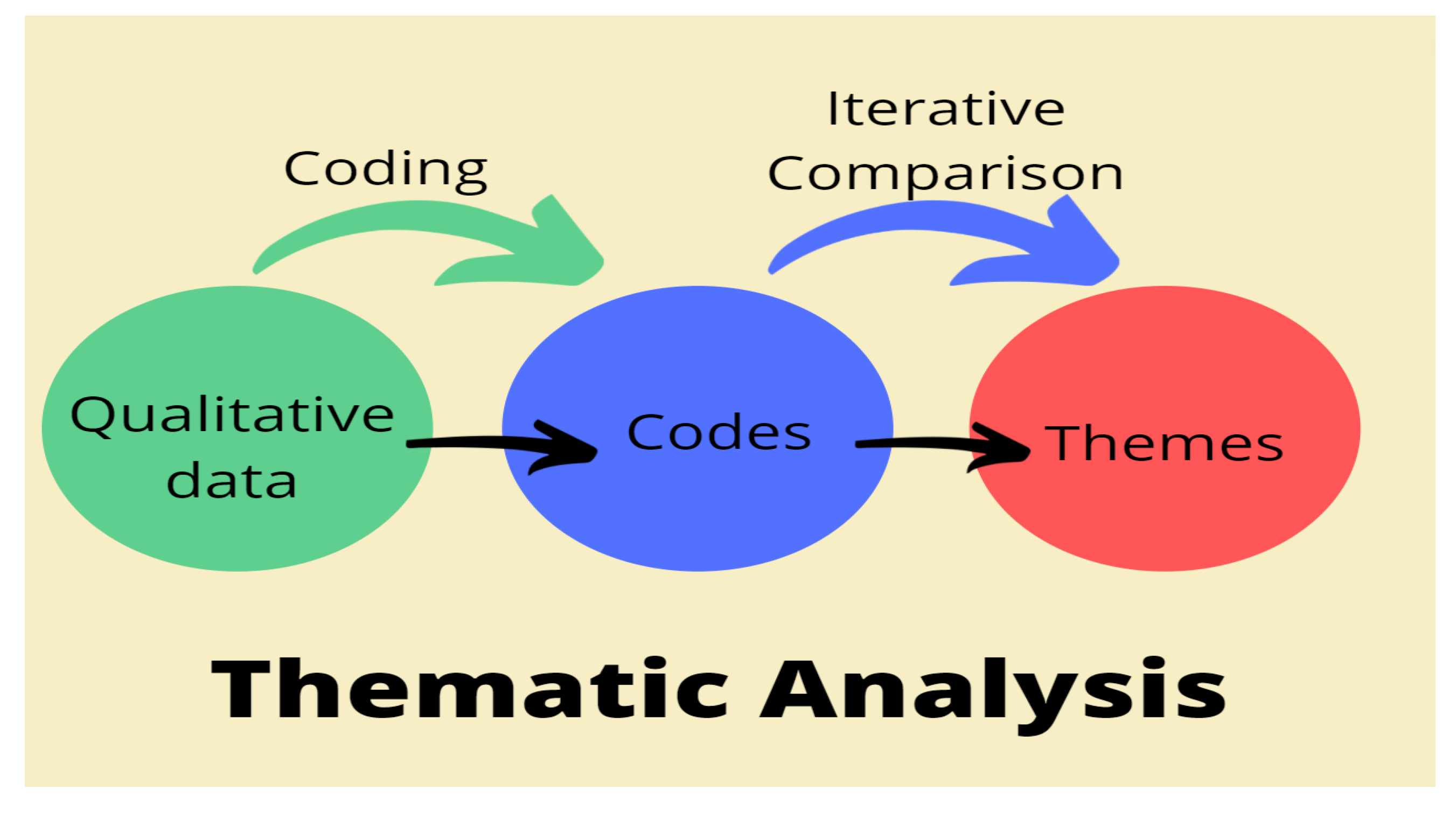

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Validity

2.5. Reliability

3. Results

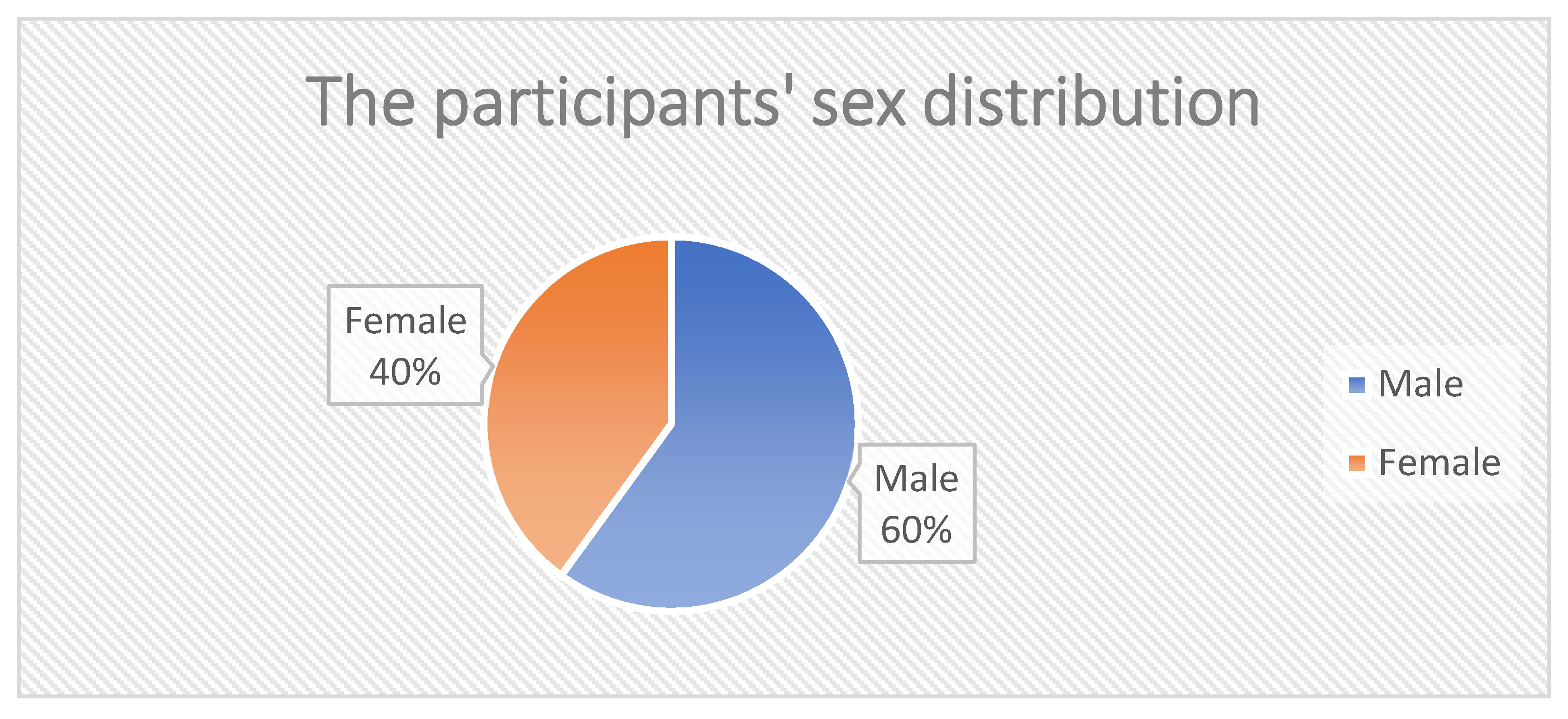

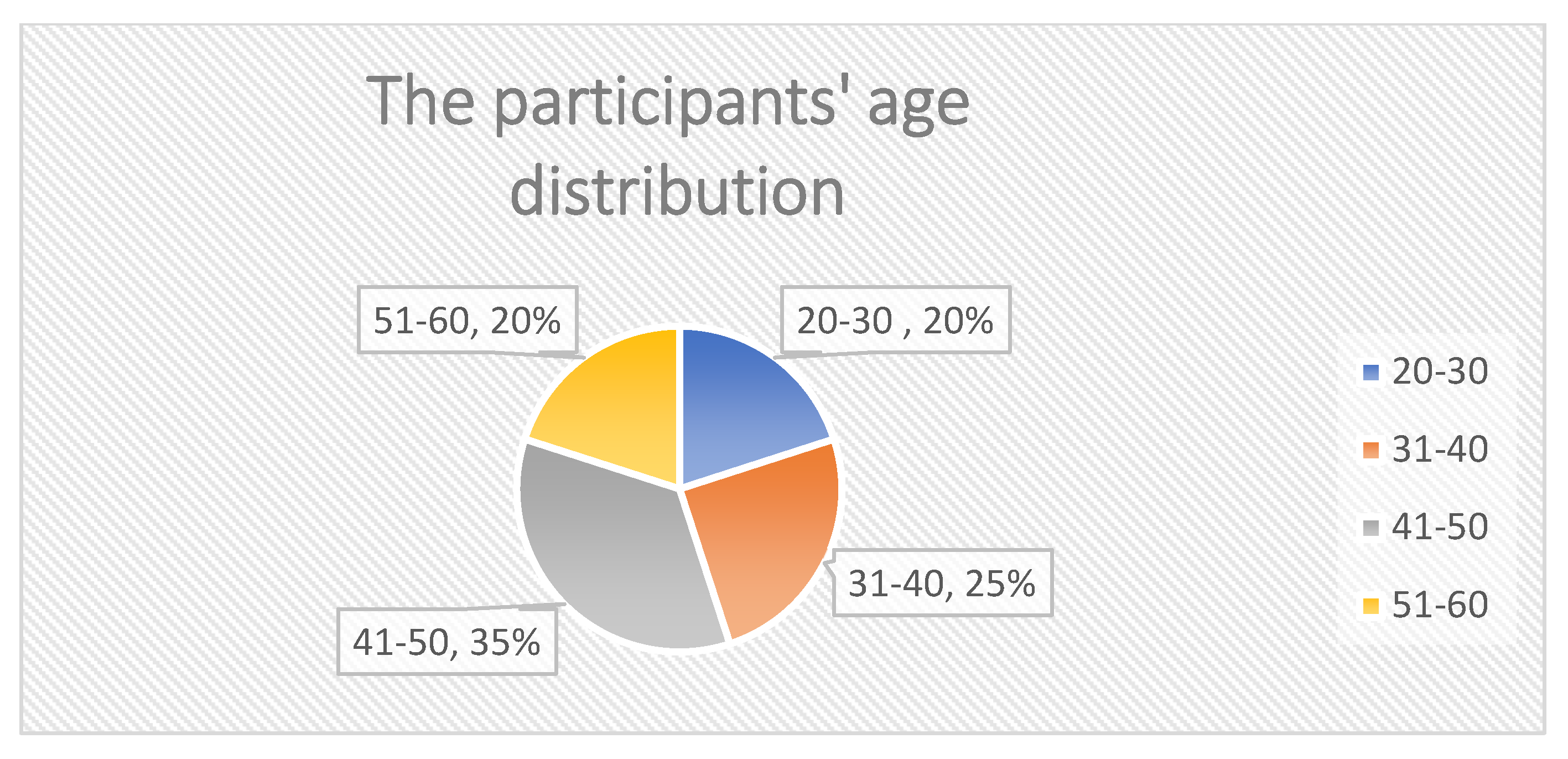

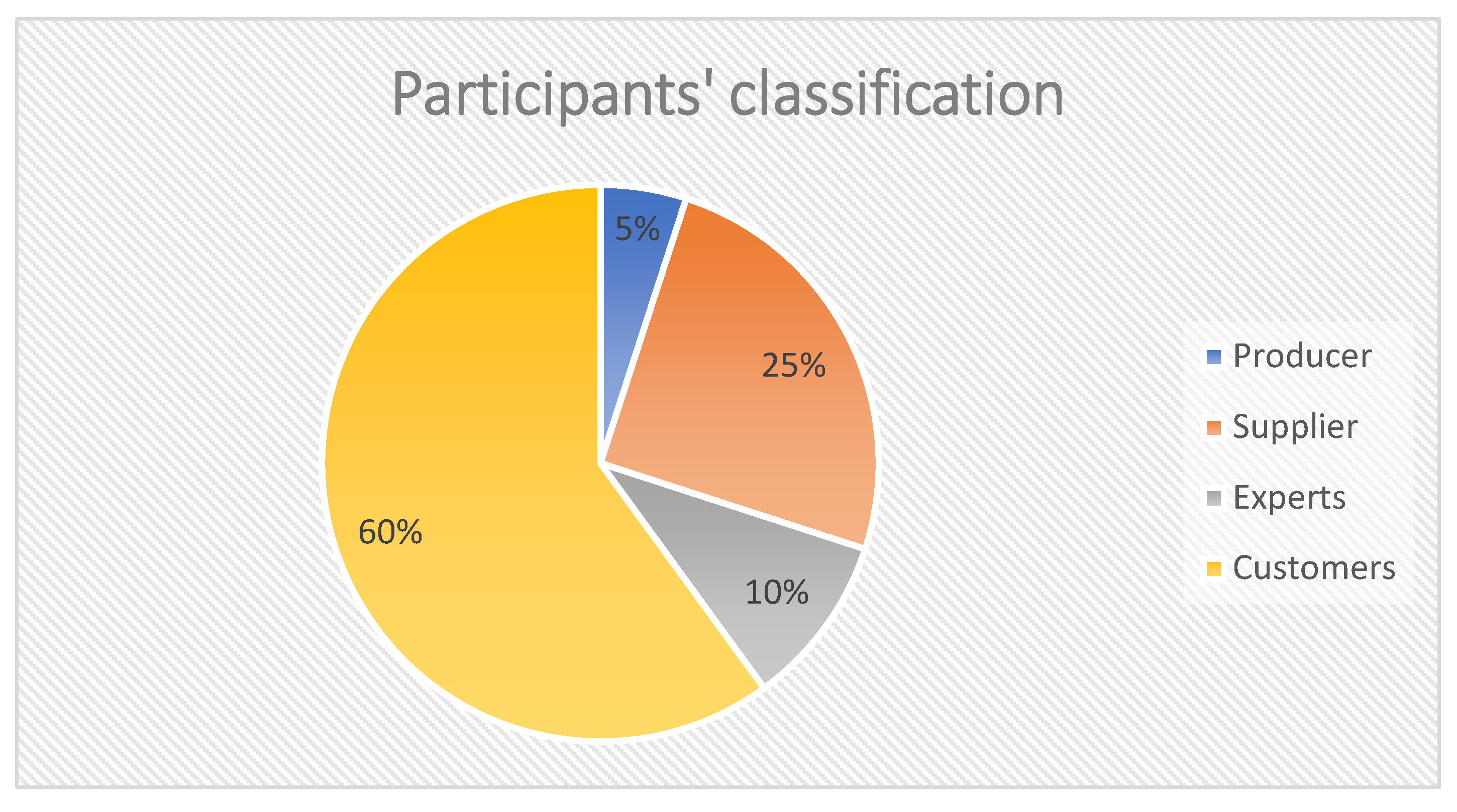

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Participants

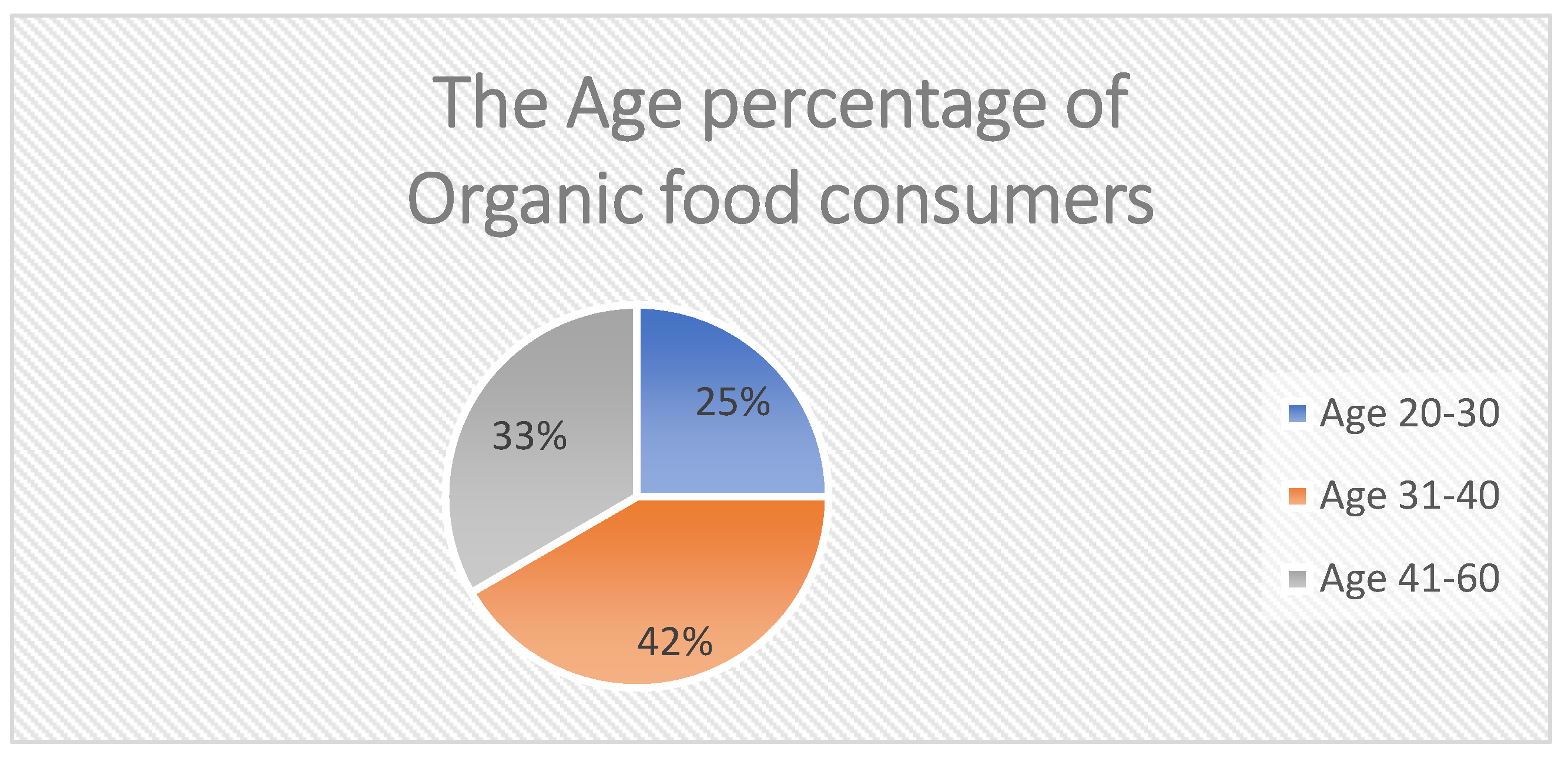

3.1.1. Customers’ Profile

3.1.2. Analysis of Consumer Responses

3.1.3. Analysis of Producers’ and Suppliers’ Responses

3.2. Influencing Factors and Motivations

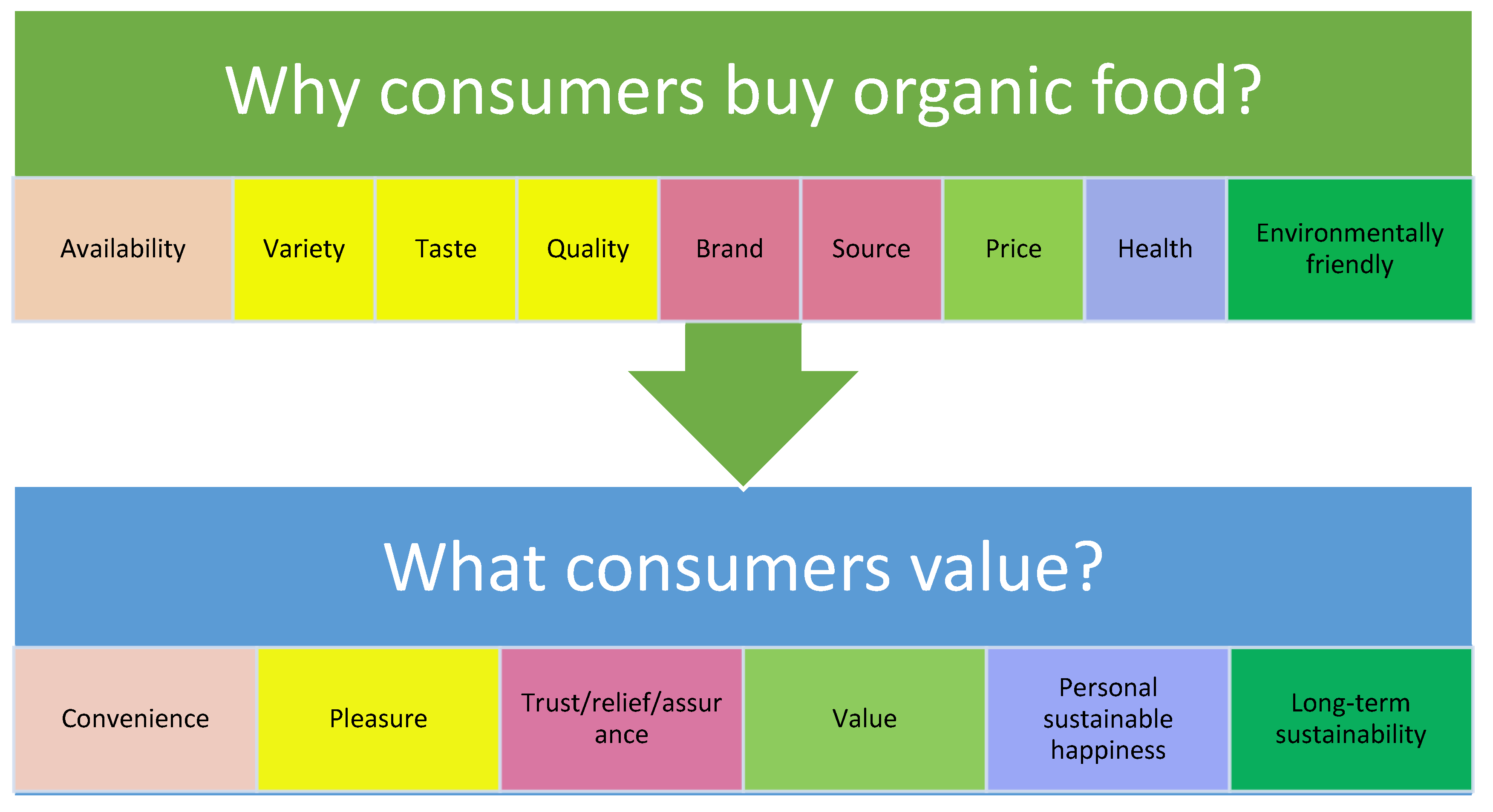

3.2.1. Why Do Customers Buy the Goods or Services You Provide?

- Convenience/Availability/Endurance

- Quality/Taste/Variety/Attractiveness

- Brand/Source

- Price

- Health

- Environment Friendliness/Social Responsibility

3.2.2. What Do Customers Really Value?

- Convenience/Efficiency/Consideration

- Pleasure

- Trust/Assurance/Reliability

- Value/Worth

- Sustainable Personal Happiness

- Long-term Sustainability

3.3. Barriers to the Purchase Decision

3.3.1. Price Premium

3.3.2. Availability

3.3.3. Attraction

3.4. Products Knowledge

3.4.1. Consumers’ Perspectives

3.4.2. Suppliers’ Perspectives

3.4.3. Producers’ and Suppliers’ Perspectives

- Education of Consumers

- Communication with Customers

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

- How can value be delivered?

- How much do customers understand the products?

- Who are the best customers for organic products?

4.2. A Comparative Discussion of the Findings and the Literature

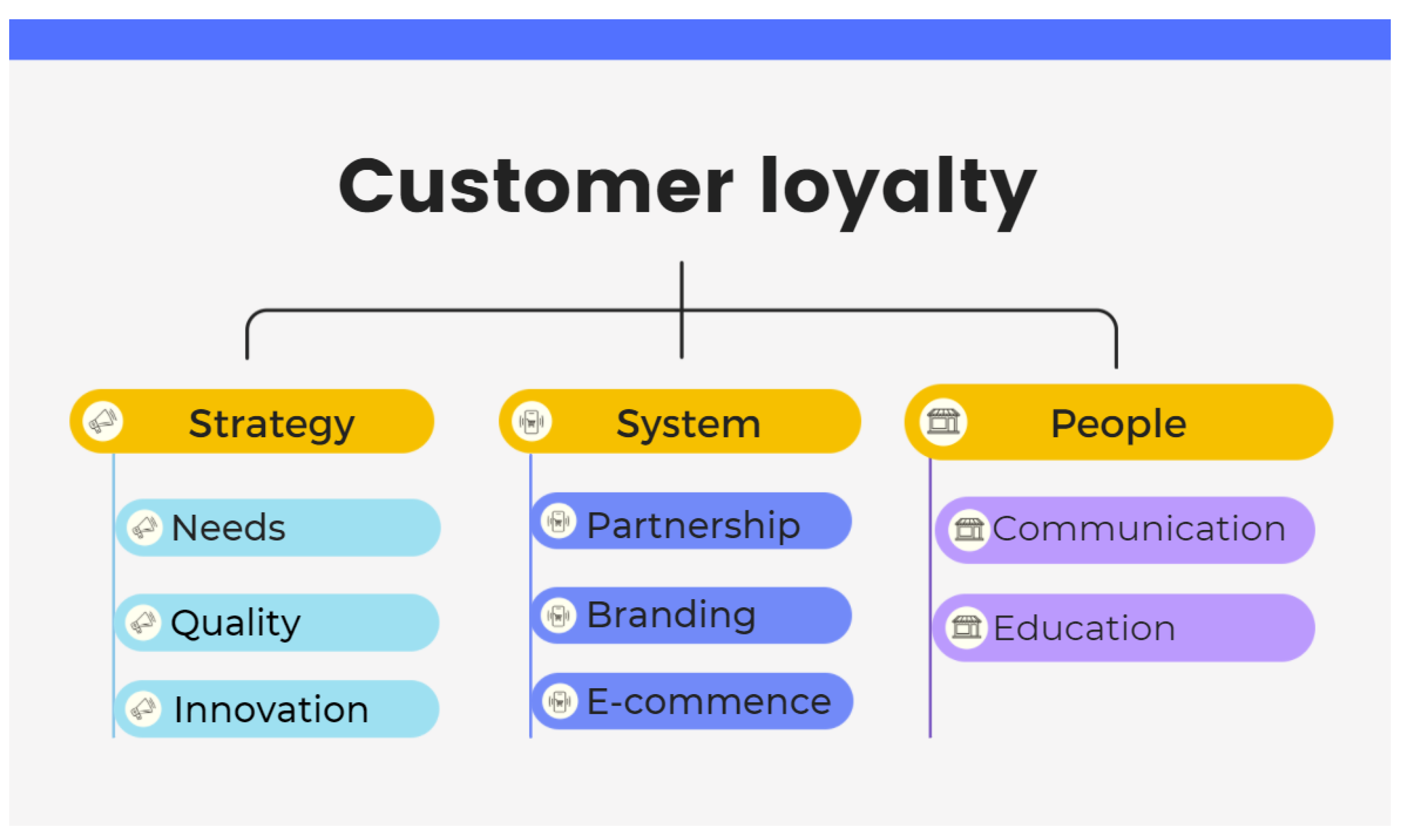

4.2.1. Value Delivery

- Availability

- Branding

- Communication

4.2.2. Education

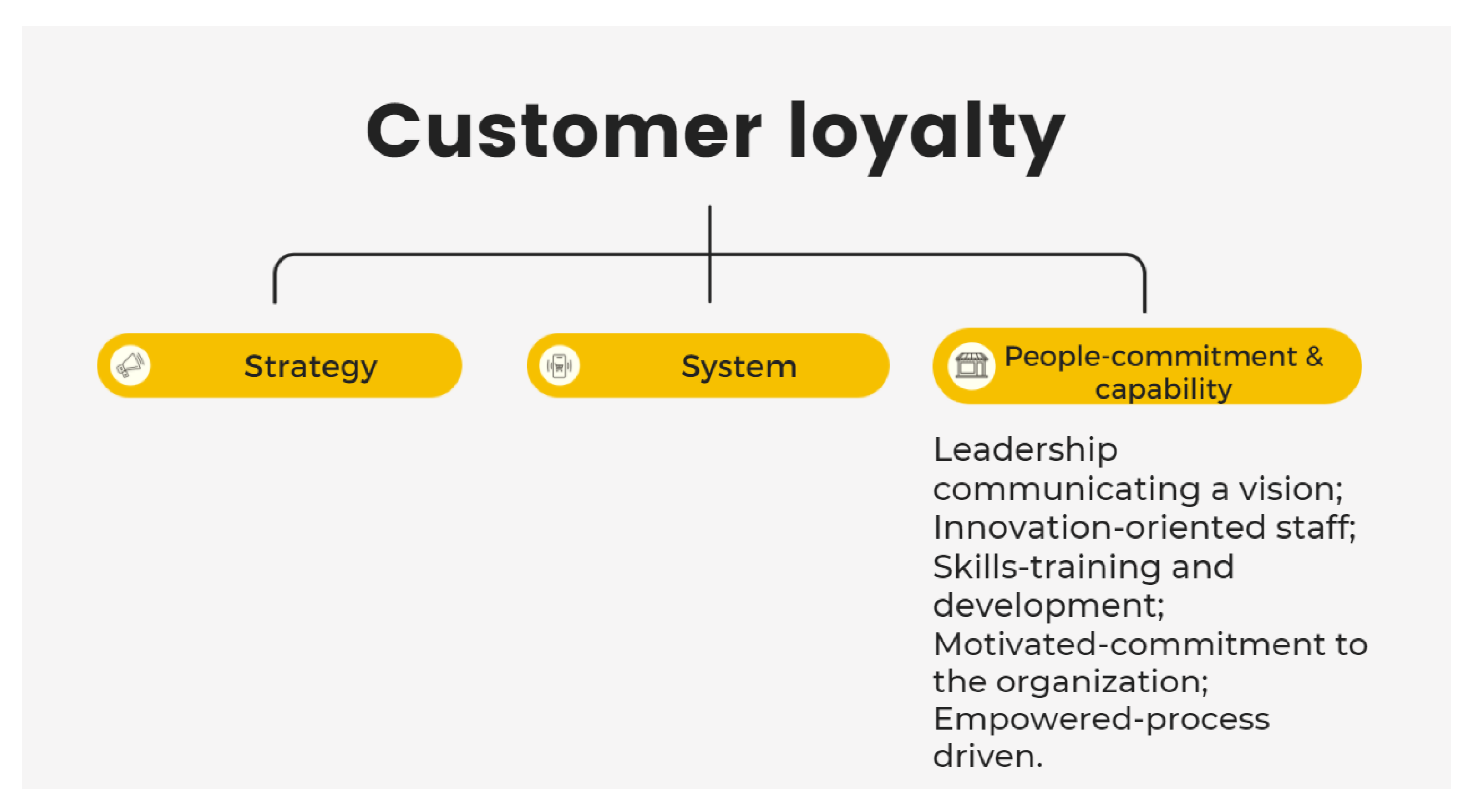

4.2.3. Dynamic Customer Focus

4.3. Summary

4.4. Implications and Recommendations

4.5. Limitations and Future Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parajuli, S.; Shrestha, J.; Ghimire, S. Organic farming in Nepal: A viable option for food security and agricultural sustainability. Arch. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2020, 5, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holla, S.M. Food in fashion modelling: Eating as an aesthetic and moral practice. Ethnography 2020, 21, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vega-Zamora, M.; Parras-Rosa, M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J. You are what you eat: The relationship between values and organic food consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaroiu, G.; Andronie, M.; Uţă, C.; Hurloiu, I. Trust management in organic agriculture: Sustainable consumption behavior, environmentally conscious purchase intention, and healthy food choices. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Pham, T.L.; Dang, V.T. Environmental Consciousness and organic food purchase intention: A moderated mediation model of perceived food quality and price sensitivity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Neumayr, L.; Moosauer, C. How to induce sales of sustainable and organic food: The case of a traffic light eco-label in online grocery shopping. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifita, I.M.E.; Seo, Y.; Ko, E.; Conroy, D. Wellbeing, sustainability, and status consumption practices. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E.L. Experiencing fashion: The interplay between consumer value and sustainability. Qual. Mark. Res. 2020, 23, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, J.; Baars, T.; Bügel, S.; Busscher, N. Organic food quality: A framework for concept, definition and evaluation from the European perspective. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 2760–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mie, A.; Andersen, H.R.; Gunnarsson, S.; Kahl, J.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Quaglio, G.; Grandjean, P. Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: A comprehensive review. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. The dynamic interaction of personal norms and environment-friendly buying behavior: A panel Study. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 1758–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Consumer decision-making with regard to organic food products. In Traditional Food Production and Rural Sustainable Development; Routledge: Farnham, UK, 2016; pp. 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Health motive and the purchase of organic food: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to predict Iranian students’ intention to purchase organic food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canova, L.; Bobbio, A.; Manganelli, A.M. Buying organic food products: The role of trust in the Theory of Planned Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, T.; Lavelle, F.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Bucher, T.; Egan, B.; Dean, M. Are the claims to blame? A qualitative study to understand the effects of nutrition and health claims on perceptions and consumption of food. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doyle, P.; Bridgewater, S. Innovation in Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajan, H.K. Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2018, 7, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blair, I. Greener products. In Greener Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Jongmans, E.; Dampérat, M.; Jeannot, F.; Lei, P.; Jolibert, A. What is the added value of an organic label? Proposition of a model of transfer from the perspective of ingredient branding. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 338–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, I.; Tabea, L. Consumer reactions to the availability of organic food in discount supermarkets. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 7, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B.; Chekima, K.; Chekima, K. Understanding factors underlying actual consumption of organic food: The moderating effect of future orientation. Food Qual. Pref. 2019, 74, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dropulić, B.; Krupka, Z. Are Consumers Always Greener on the Other Side of the Fence? Factors That Influence Green Purchase Intentions–The Context of Croatian and Swedish Consumers. Market-Tržište 2020, 32, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; Singh, P.K.; Yadav, R. Application of consumer style inventory (CSI) to predict young Indian consumer’s intention to purchase organic food products. Food Qual. Pref. 2018, 68, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, F. On the value of commitment and availability guarantees when selling to strategic consumers. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosi, A.; Zerbini, C.; Pellegrini, N.; Scazzina, F.; Brighenti, F.; Lugli, G. How to improve food choices through vending machines: The importance of healthy food availability and consumers’ awareness. Food Qual. Pref. 2017, 62, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, C.P.; Sousa, B.M. Green consumer behavior and its implications on brand marketing strategy. In Green Marketing as a Positive Driver Toward Business Sustainability; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 9–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysochou, P. Food health branding: The role of marketing mix elements and public discourse in conveying a healthy brand image. J. Mark. Commun. 2010, 16, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, K.; Zha, Y.; Bi, G. Optimal pricing and availability strategy of a bike-sharing firm with time-sensitive customers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, D.; Ploeger, A. The potential influence of organic food consumption and intention-behavior gap on consumers’ subjective wellbeing. Foods 2020, 9, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Paço, A. Moral disengagement: A guilt-free mechanism for non-green buying behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, S.; Ellis, D. Creativity in marketing communication to overcome barriers to organic produce purchases: The case of a developing nation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bermúdez, R.; Miranda, M.; Orjales, I.; Ginzo-Villamayor, M.J.; Al-Soufi, W.; López‐Alonso, M. Consumers’ perception of and attitudes towards organic food in Galicia (Northern Spain). Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Han, X.; Ding, L.; He, M. Organic food corporate image and customer co-developing behavior: The mediating role of consumer trust and purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkoska, A.T.; Daniloski, D.; D’Cunha, N.M.; Naumovski, N.; Broach, A.T. Edible packaging: Sustainable solutions and novel trends in food packaging. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 109981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padel, S.; Röcklinsberg, H.; Schmid, O. The implementation of organic principles and values in the European Regulation for organic food. Food Policy 2009, 34, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filippini, R.; De Noni, I.; Corsi, S.; Spigarolo, R.; Bocchi, S. Sustainable school food procurement: What factors do affect the introduction and the increase of organic food? Food Policy 2018, 76, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usharani, M.; Gopinath, R. A Study on Consumer Behaviour on Green Marketing with reference to Organic Food Products in Tiruchirappalli District. Int. J. Res. Instinct 2021, 3, 268–279. [Google Scholar]

- Niggli, U.; Slabe, A.; Schmid, O.; Halberg, N.; Schlüter, M. Vision for an Organic Food and Farming Research Agenda 2025. Organic Knowledge for the Future. Organic Knowledge for the Future; Technology Platform Organics. IFOAM Regional Group European Union (IFOAM EU Group); Brussels and International Society of Organic Agriculture Research (ISOFAR): Bonn, Germany, 2008; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/13439/ (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Scalvedi, M.L.; Saba, A. Exploring local and organic food consumption in a holistic sustainability view. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Paul, C.; Barnett, C.; Malpass, A. The spaces and ethics of organic food. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, B.; Martini, M.; Fedi, A.; Loera, B.L.; Elliott, C.; Dean, M. Consumer trust in organic food and organic certifications in four European countries. Food Control 2022, 133, 108484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughner, R.S.; McDonagh, P.; Stanton, J.; Shultz, C.; Prothero, A. Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Chung, J. What drives consumers to certain retailers for organic food purchase: The role of fit for consumers’ retail store preference. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Meeting | Type | Age (years) | Sex | Industry and Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M/F) | ||||

| 1. | C-1, Organic food consumer/ Obesity problem | 39 | Male | PhD student at the University of Ulster/Lecturer |

| 2. | S-1, Food supplier | 45 | Male | Sales manager for Northern Ireland, McColgan’s Quality Foods |

| 3. | C-2, Non-organic food consumer | 40 | Female | Householder, nursing background |

| 4. | S-2, Food supplier/Local farm shop | 44 | Male | Owner of Gentender Ltd. |

| 5. | C-3, Health food consumer | 24 | Female | A social worker from Rathbone, Belfast |

| 6. | C-4, Health food lover/ Consumer/ Vegetarian | 25 | Female | Charity administrator |

| 7. | C-5, Potential organic food consumer | 55 | Female | Senior secondary school teacher |

| 8. | C-6, C-7, Non-organic food consumer/ Obesity and chronic diseases | 50 58 | Female Male | Nurse Teacher (this was a couple) |

| 9. | S-3, Food supplier | 50 | Male | Ireland commercial manager at Dale Farm Ltd., Belfast, UK |

| 10. | C-8, Organic and health food consumer | 26 | Male | PhD student at the University of Ulster (European surveillance of congenital anomalies benefit risk analysis in food) |

| 11. | C-9, Organic food consumer | 39 | Female | Landscape business director, self-employed |

| 12. | E-1, E-2, Organic business expert | 40/23 | Male | Agriculture and rural development/ Food standard agency |

| 13. | P-1, Organic food producer S-4, Organic food supplier | 42/ 43 | Male/ Male | Owner of Burren Organic Farm Marketer at Burren Organic Farm |

| 14. | S-5, Organic food supplier | 58 | Female | Organic products store manager |

| 15. | C-10, Potential consumer | 36 | Male | Fitness instructor |

| 16. | C-11, Potential consumer | 42 | Male | PhD, University lecturer |

| 17. | C-12, Organic consumer | 58 | Female | Vice-chancellor in a primary school |

| Age | Sex | Family Status | Employment Status | Health Status | Organic Food Consumers | Nationality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 39 | M | Married w/1 child | PhD/ University Lecturer | Obesity | Yes | Nigeria |

| C-2 | 40 | F | Married w/1 child | Household/ Nursing background | OK | No | UK |

| C-3 | 24 | F | Single | Social worker | Good | Casually | Germany |

| C-4 | 25 | F | Single with partner | Administrator | Good | Casually | UK, British born Turkish, |

| C-5 | 55 | F | Married w/1 child | Senior secondary school teacher | Good | Yes | UK |

| C-6 | 50 | F | Married w/2 child | Teaching Assistant/ Nursing background | Good | Casually | UK |

| C-7 | 58 | M | Married w/2 child | Part-time teacher | Obesity | No | UK |

| C-8 | 26 | M | Single | PhD student | Good | Yes | Dutch |

| C-9 | 39 | F | Married no child | Self-employment | Good | Yes | UK |

| C-10 | 36 | M | Single | Fitness instructor | Good | Rarely | UK |

| C-11 | 42 | M | Single | PhD/University Lecturer | Good | Rarely | Iran |

| C-12 | 58 | M | Married w/1 child | Retired businessman | Normal, Cancer recovered | Rarely | UK |

| Ranked | Q1. Influenced Factors | Q2. Motivation | Q3. Barriers | Q4. Eco-Concern | Q5. Knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Availability | Tasty | Availability | Yes | Insufficient |

| 2. | Variety | Health concept | Culture: eating habits | ||

| 3. | Taste | Eco-friendly | Price | ||

| 4. | Quality | Cost-effective | Insufficient knowledge of organic food | ||

| 5. | Brand, Source | Health concept | Value of price | ||

| 6. | Price | Food security | Source | ||

| 7. | Health-conscious, environmentally friendly |

| Ranked | Q1. Motivation | Q2. Barriers | Q3. Eco. Concern | Q4. Knowledge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Availability | Strategy | Yes | Insufficient | |

| 2. | Variety | Price, culture, eating habits, knowledge of organic food | Yes | Insufficient | |

| 3. | Taste, quality | Taste, high cost, capability | Yes | Insufficient | |

| 4. | Brand, source | Price | Yes | Insufficient | |

| 5. | Health concept, profit | Knowledge and price | Yes | Insufficient | |

| Questions for Research | Why Do Customers Buy the Goods or Services You Provide? | What Do Customers Value? | How Could That Value Be Delivered? | Literature Applied |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finding | -Convenience/ Availability -Variety -Taste -Quality -Brand/Source -Price -Health -Eco-issue/ Social responsibility | -Efficiency/Consideration -Pleasure -Trust/Assurance/Relief -Value -Sustainable happiness -Long-term sustainability | -Availability (Place) -Communication (Promotion) -Education (Product) | Market-led innovation (Doyle Bridgewater, 2012); The innovator’s solution (Christensen, 2003). |

| Discussion | Availability | Branding | Communication |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, S.C.-I.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Arya, F. Innovative Strategies to Fuel Organic Food Business Growth: A Qualitative Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052941

Chen SC-I, Liu C, Wang Z, Arya F. Innovative Strategies to Fuel Organic Food Business Growth: A Qualitative Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052941

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Sonia Chien-I, Chenglian Liu, Zhenyuan Wang, and Farid Arya. 2022. "Innovative Strategies to Fuel Organic Food Business Growth: A Qualitative Research" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052941

APA StyleChen, S. C.-I., Liu, C., Wang, Z., & Arya, F. (2022). Innovative Strategies to Fuel Organic Food Business Growth: A Qualitative Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052941