Building a Health Literacy Indicator from Angola Demographic and Health Survey in 2015/2016

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Conceptualization and Construction of a Measure of Health Literacy for Angola

2.3. Validity

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Deriving a Measure of Health Literacy by Factor Analysis

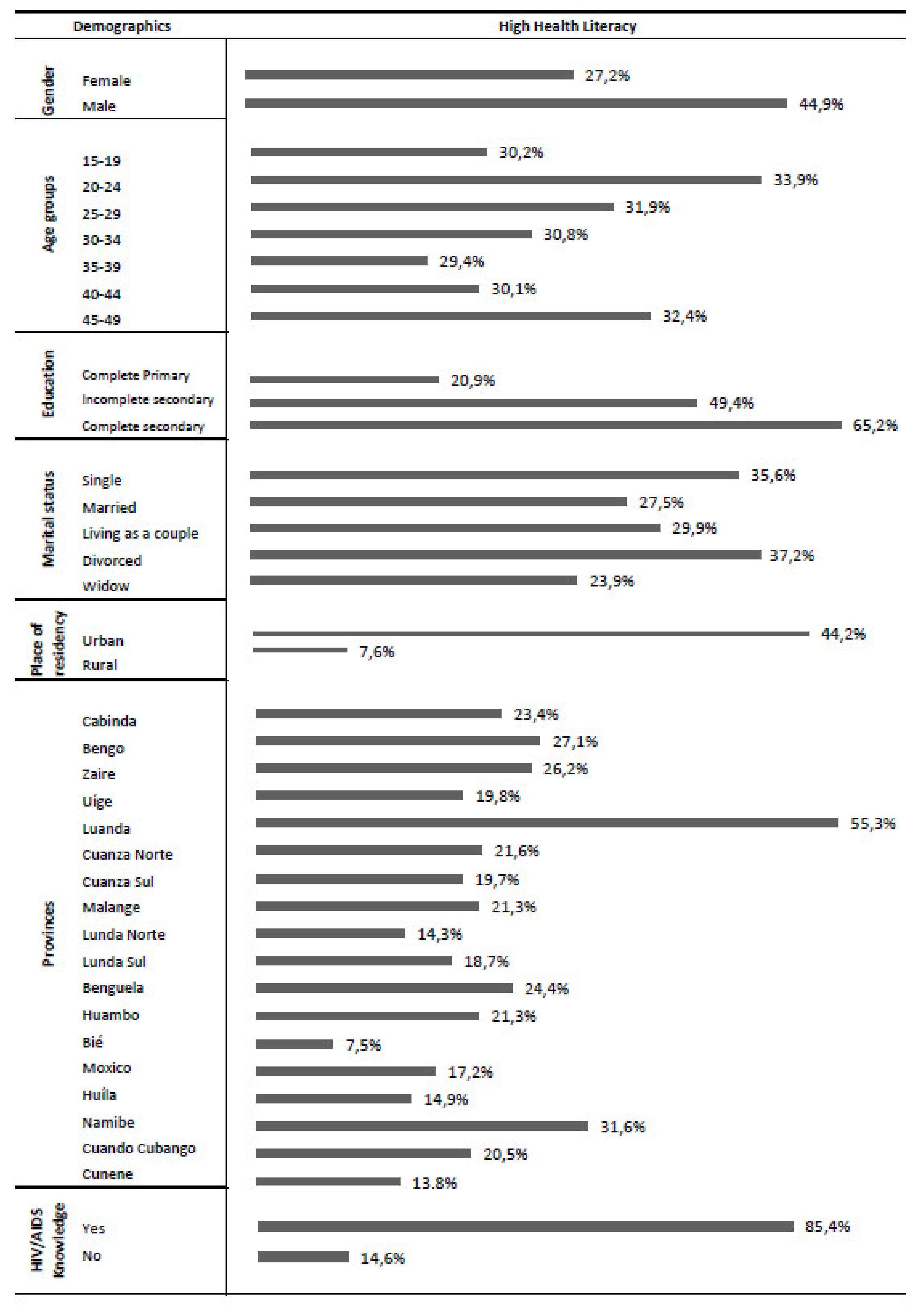

3.2. Determinants of Health Literacy

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

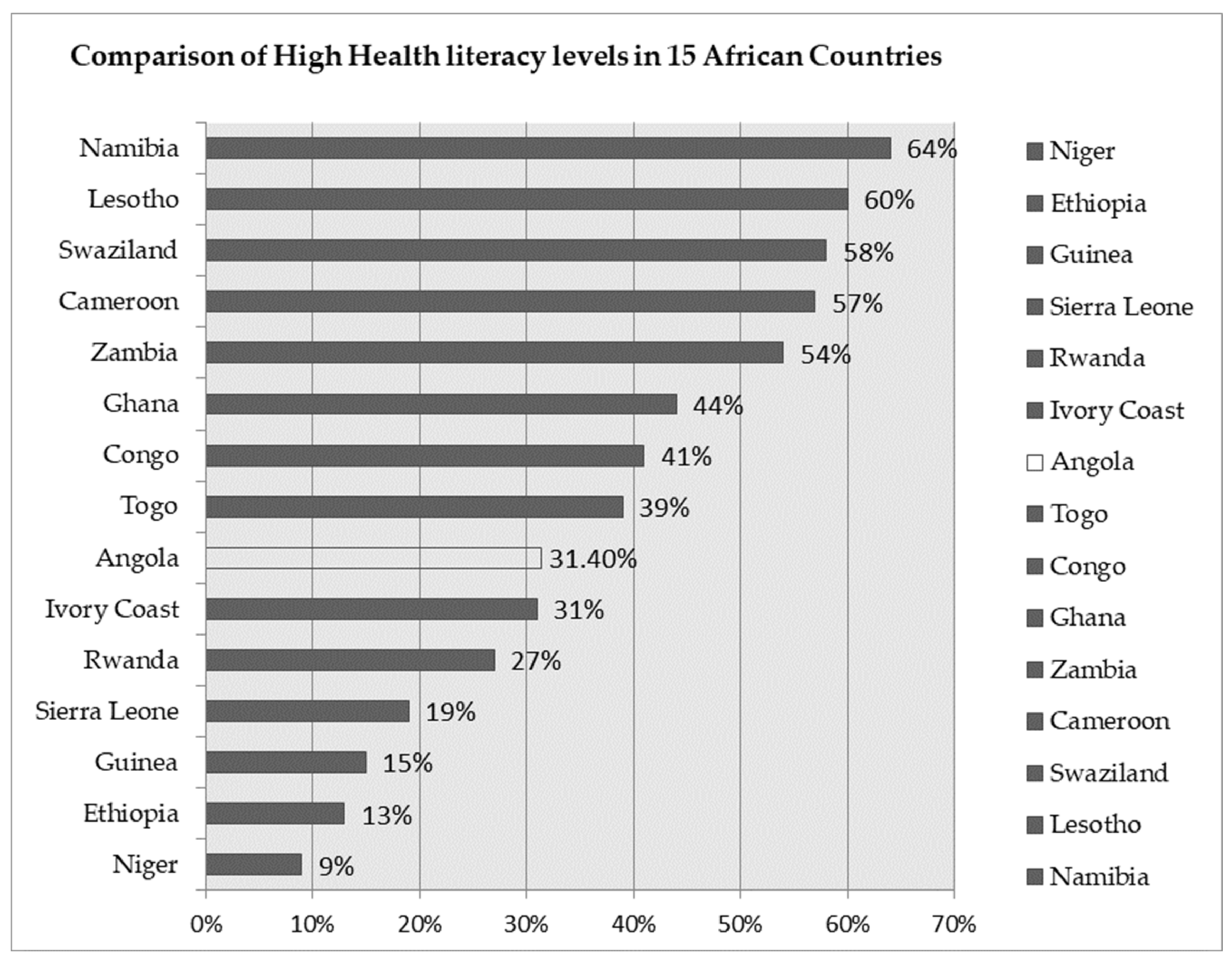

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hernandez, L.; French, M.; Parker, R. Roundtable on Health Literacy: Issues and Impact. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 2017, 240, 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Bohlman, L.; Panzer, A.M.; Kindig, D.A. (Eds.) Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion; The National Academies, Committee on Health Literacy: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; Consortium Health Literacy Project, E. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Levin-Zamir, D.; Pinheiro, P.; Sørensen, K. Handbook of Health Literacy Research, Practice and Policy across the Lifespan; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, M.A.M.; Franklin, G.V. Health Literacy: An Intervention to Improve Health Outcomes. In Strategies to Reduce Hospital Mortality in Lower and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) and Resource-Limited Settings; Mullings, J., Thoms-Rodriguez, C.-A., McCaw-Binns, A.M., Paul, T., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dukić, N.; Blecich, A.A.; Cerović, L. Economic Implications of Insufficient Health Literacy. Econ. Res. 2013, 26, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. Poor health literacy: A ‘hidden’ risk factor. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010, 7, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loer, A.-K.M.; Domanska, O.M.; Stock, C.; Jordan, S. Subjective Generic Health Literacy and Its Associated Factors among Adolescents: Results of a Population-Based Online Survey in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccolini, V.; Isonne, C.; Salerno, C.; Giffi, M.; Migliara, G.; Mazzalai, E.; Turatto, F.; Sinopoli, A.; Rosso, A.; De Vito, C.; et al. The association between adherence to cancer screening programs and health literacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2022, 155, 106927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzo, J.; Reyes, D.; Webel, A. A Systematic Review of Health Literacy Interventions for People Living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz de Almeida, C.; Veiga, A. Literacia em saúde e capacitação do idoso na prevenção da diabetes mellitus tipo2 em contexto comunitário. JIM-J. Investig. Méd. 2020, 1, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tique, J.A.; Howard, L.M.; Gaveta, S.; Sidat, M.; Rothman, R.L.; Vermund, S.H.; Ciampa, P.J. Measuring Health Literacy Among Adults with HIV Infection in Mozambique: Development and Validation of the HIV Literacy Test. Aids Behav. 2017, 21, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccolini, V.; Rosso, A.; Di Paolo, C.; Isonne, C.; Salerno, C.; Migliara, G.; Prencipe, G.P.; Massimi, A.; Marzuillo, C.; De Vito, C.; et al. What is the Prevalence of Low Health Literacy in European Union Member States? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.V.; Veiga, A. Social Determinants and Health Literacy of the Elderly: Walk to Well-Being. Open Access Libr. J. Lisbon 2020, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, S.G.S.; Osborne, R.H. Health Literacy Toolkit for Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Series of Information Sheets to Empower Communities and Strengthen Health Systems; World Health Organization: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Magon, A.; Arrigoni, C.; Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Moia, M.; Palareti, G.; Caruso, R. The effect of health literacy on vaccine hesitancy among Italian anticoagulated population during COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of health engagement. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, Z.; Dilcen, H.Y.; Dolu, İ. The mediating role of health literacy on the relationship between health care system distrust and vaccine hesitancy during COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, K.J.; Dodd, R.H.; Cvejic, E.; Ayrek, J.; Batcup, C.; Isautier, J.M.; Copp, T.; Bonner, C.; Pickles, K.; Nickel, B.; et al. Health literacy and disparities in COVID-19-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours in Australia. Public Health Res. Pract. 2020, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cui, G.; Kaminga, A.C.; Cheng, S.; Xu, H. Associations Between Health Literacy, eHealth Literacy, and COVID-19-Related Health Behaviors Among Chinese College Students: Cross-sectional Online Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Viera, A.; Crotty, K.; Holland, A.; Brasure, M.; Lohr, K.N.; Harden, E.; et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: An updated systematic review. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess (Full Rep.) 2011, 199, 1–941. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zeng, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, F.; Sharma, M.; Lai, W.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, G.; Yuan, J.; Zhao, Y. Assessment Tools for Health Literacy among the General Population: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrauben, S.J.; Wiebe, D.J. Health literacy assessment in developing countries: A case study in Zambia. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 32, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, H.F.; Alber, J.M.; Schrauben, S.J.; Mazzola, C.M.; Wiebe, D.J. Constructing a measure of health literacy in Sub-Saharan African countries. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 35, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for International Development (USAID). The Demographic and Health Survey Program; USAID: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO, Institute for Statistics. Angola Profile. Education and Literacy. 2021. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/ao?theme=education-and-literacy#slideoutmenu (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Agency, C.I. Angola Profile. 2020. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_ao.html (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today:Inequalities in human development in the 21st century. In Overview Human Development Report; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Inquérito de Indicadores Múltiplos e de Saúde em Angola 2015–2016; Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE): Lisbon, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Health literacy and the Millennium Development Goals: United Nations. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 (Suppl. 2), 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hill, M.M.; Hill, A. Investigação por Questionário, 2nd ed.; Edições Sílabo: Coimbra, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Análise Multivariada de Dados; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program. Human Development Reports. Country Profiles. Education. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/NLD (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Almaleh, R.; Helmy, Y.; Farhat, E.; Hasan, H.; Abdelhafez, A. Assessment of health literacy among outpatient clinics attendees at Ain Shams University Hospitals, Egypt: A cross-sectional study. Public Health 2017, 151, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, P.A.; Phillips, D.R.; Gyasi, R.M.; Koduah, A.O.; Edusei, J. Health literacy and self-perceived health status among street youth in Kumasi, Ghana. Cogent Med. 2017, 4, 1275091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Tutu, R.A.; Boateng, J.; Busingye, J.D.; Elavarthi, S. Self-reported functional, communicative, and critical health literacy on foodborne diseases in Accra, Ghana. Trop. Med. Health 2018, 46, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.-Y.; Anthony, E.; Gabriel, G. Comprehensive Health Literacy Among Undergraduates: A Ghanaian University-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Health Lit. Res. Practice. 2019, 3, e227–e237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Jafar, T.H.; Chaturvedi, N. Self-rated health in Pakistan: Results of a national health survey. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.; Zafar, A.; Mohib, A.; Baig, M. A Gender-based Comparison in Health Behaviors and State of Happiness among University Students. Cureus 2018, 10, e2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, M.; Mutonyi, H. Literacy in Rural Uganda: The Critical Role of Women and Local Modes of Communication. Diaspora Indig. Minority Educ. 2010, 1, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G.; Geary, D.C. Gender differences in the pathways to higher education. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B.I.I.; Yawson, A.E.; Nguah, S.; Agyei-Baffour, P.; Emmanuel, N.; Ayesu, E. Effect of socio-economic factors in utilization of different healthcare services among older adult men and women in Ghana. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zon, H.; Pavlova, M.; Groot, W. Factors associated with access to healthcare in Burkina Faso: Evidence from a national household survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridas, R.; Supreetha, S.; Ajagannanavar, S.L.; Tikare, S.; Maliyil, M.J.; Kalappa, A.A. Oral health literacy and oral health among adults attending dental college hospital in India. J. Int. Oral Health 2014, 6, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Janse van Rensburg, Z. Levels of health literacy and English comprehension in patients presenting to South African primary healthcare facilities. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2020, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, M.; Nel, M.; Van Rensburg-Bonthuyzen, E.J. Development of a Sesotho health literacy test in a South African context. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019, 11, e1–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angola, I.N.d.E.d. Inquérito Integrado Sobre o Bem-Estar da População, IBEP.; INE: Luanda, Angola, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyinu, Y.A.; Femi-Adebayo, T.T.; Adebayo, B.I.; Abdurraheem-Salami, I.; Odusanya, O.O. Health literacy: Prevalence and determinants in Lagos State, Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golboni, F.; Nadrian, H.; Najafi, S.; Shirzadi, S.; Mahmoodi, H. Urban-rural differences in health literacy and its determinants in Iran: A community-based study. Aust. J. Rural Health 2018, 26, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerma, J.S.; Sommerfelt, A.E. Demographic and health surveys: DHS contributions and limitations. World Health Stat. Q. 1993, 46, 222–226. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Characteristics (n = 19,785) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Categories | % |

| Gender | Female | 71.6 |

| Male | 27.2 | |

| Age groups | 15–19 | 24.9 |

| 20–24 | 20.6 | |

| 25–29 | 17 | |

| 45–49 | 6.6 | |

| Marital status | Not married | 46.8 |

| Married | 53.2 | |

| Residence | Urban | 70.3 |

| Rural | 29.7 | |

| Region | Cabinda | 2.4 |

| Bengo | 1.1 | |

| Zaire | 2.1 | |

| Uíge | 4.9 | |

| Luanda | 39.6 | |

| Cuanza Norte | 1.2 | |

| Cuanza Sul | 6.8 | |

| Malange | 3.1 | |

| Lunda Norte | 2.5 | |

| Lunda Sul | 1.6 | |

| Benguela | 8.1 | |

| Huambo | 6.4 | |

| Bié | 4 | |

| Moxico | 1.8 | |

| Huíla | 8 | |

| Namibe | 1.2 | |

| Cuando Cubango | 1.7 | |

| Cunene | 3.6 | |

| Level of Education | No education | 0.3 |

| Incomplete primary | 0.1 | |

| Complete primary | 40.6 | |

| Incomplete secondary | 29.6 | |

| Complete secondary | 22.6 | |

| Higher Education Level | 6.8 | |

| Variables | Categories | % of People Responding Yes |

|---|---|---|

| Health literacy | Primary school education | 66.3 |

| Able to read whole sentence or part | 63.1 | |

| Read magazine at least once per week | 37 | |

| Listen to radio at least once per week | 31.2 | |

| Watch TV at least once per week | 19.5 | |

| Heard family planning information from magazine | 13.2 | |

| Heard family planning information from radio | 28.3 | |

| Heard family planning information from TV | 29.9 | |

| Heard family planning information from posters | 13.2 | |

| Heard family planning information from pamphlets | 13.2 | |

| Knowledge of HIV/AIDS | Knows place to get an AIDS test | 47.8 |

| Reduce chance of HIV by only having one sex partner without HIV | 85.4 | |

| Cannot get HIV from a mosquito bite | 67.4 | |

| Reduce chance of HIV by always using condoms correctly during sex | 81.6 | |

| People can get HIV if they share food with someone infected with HIV | 69.6 | |

| A healthy-looking person can have AIDS | 75.1 |

| N = 19,738 | Unadjusted High Health Literacy OR (IC 95%) | Adjusted High Health Literacy OR (IC 95%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 0.460 (0.426–0.497) | 0.599 (0.545–0.659) |

| Female | ref | ref |

| Age groups, years | ||

| 15–19 | 0.903 (0.786–1.037) | 0.414 (0.340–0.505) |

| 20–24 | 1.071 (0.929–1.234) | 0.625 (0.518–0.753) |

| 25–29 | 0.978 (0.844–1.134) | 0.677 (0.561–0.818) |

| 30–34 | 0.929 (0.795–1.087) | 0.797 (0.652–0.973) |

| 35–39 | 0.871 (0.742–1.023) | 0.907 (0.739–1.112) |

| 40–44 | 0.899 (0.762–1.059) | 0.879 (0.715–1.082) |

| 45–49 | ref | ref |

| Education | ||

| ≥Complete secondary and more | 4.830 (4.459–5.231) | 3.821 (3.491–4.181) |

| ≤Complete primary | ref | ref |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1.204 (0.900–1.610) | 0.910 (0.629–1.317) |

| Living as a couple | 1358 (1.029–1.792) | 1.108 (0.778–1.577) |

| Single | 1.759 (1.332–2.323) | 1.046 (0.725–1.507) |

| Separated | 1.082 (0.795–1.474) | 0.773 (0.525–1.138) |

| Divorced | 1.947 (0.992–3.821) | 1.012 (0.444–2.308) |

| widow | ref | ref |

| Location of residence | ||

| Urban | 9.717 (8.728–10.817) | 5.316 (4.707–6.004) |

| Rural | ref | ref |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos, N.N.V.; Fronteira, I.; Martins, M.R.O. Building a Health Literacy Indicator from Angola Demographic and Health Survey in 2015/2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052882

Ramos NNV, Fronteira I, Martins MRO. Building a Health Literacy Indicator from Angola Demographic and Health Survey in 2015/2016. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052882

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos, Neida Neto Vicente, Inês Fronteira, and Maria Rosário Oliveira Martins. 2022. "Building a Health Literacy Indicator from Angola Demographic and Health Survey in 2015/2016" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052882

APA StyleRamos, N. N. V., Fronteira, I., & Martins, M. R. O. (2022). Building a Health Literacy Indicator from Angola Demographic and Health Survey in 2015/2016. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052882