Restriction of Access to Healthcare and Discrimination of Individuals of Sexual and Gender Minority: An Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights from an Ethical Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

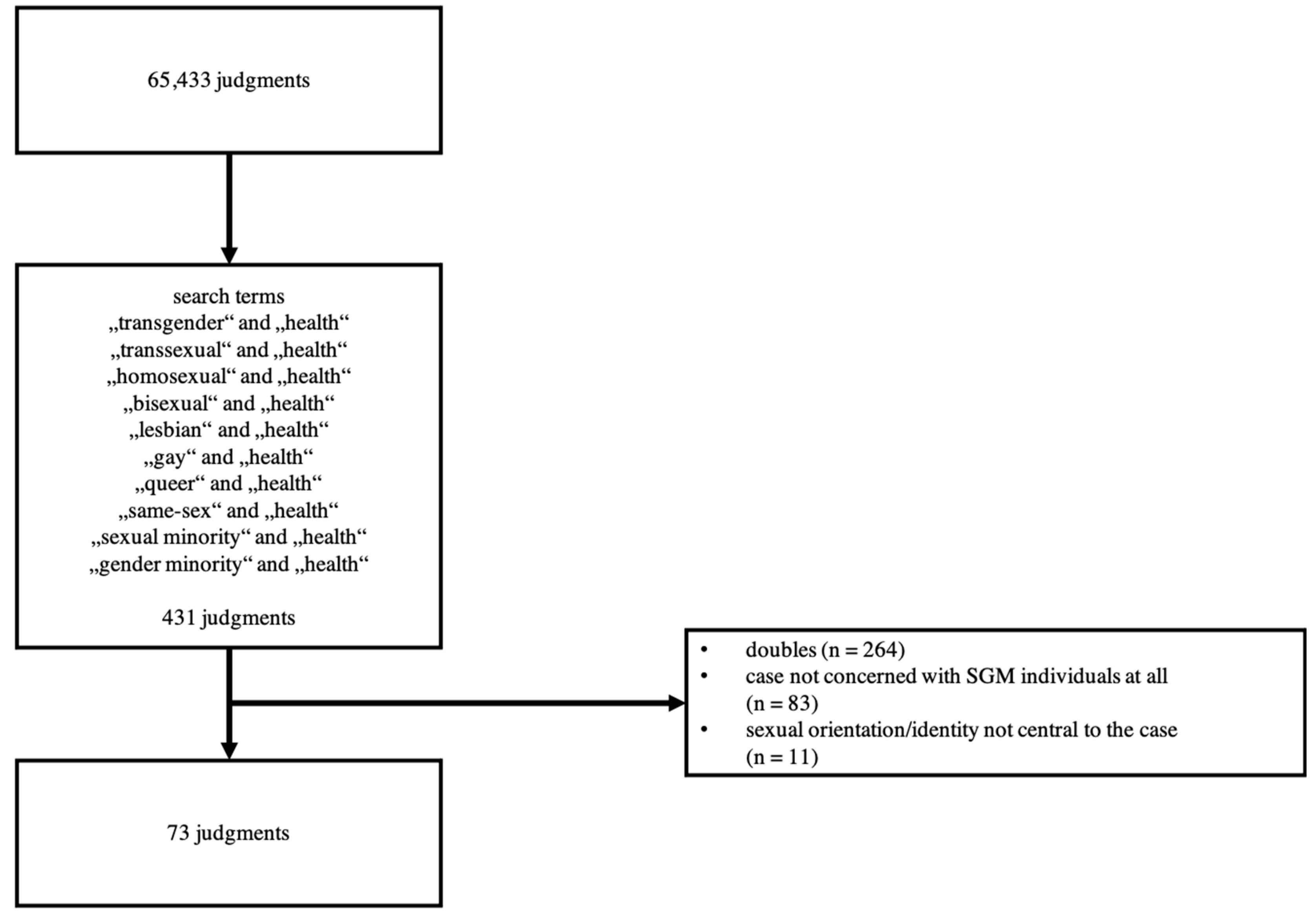

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.2. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

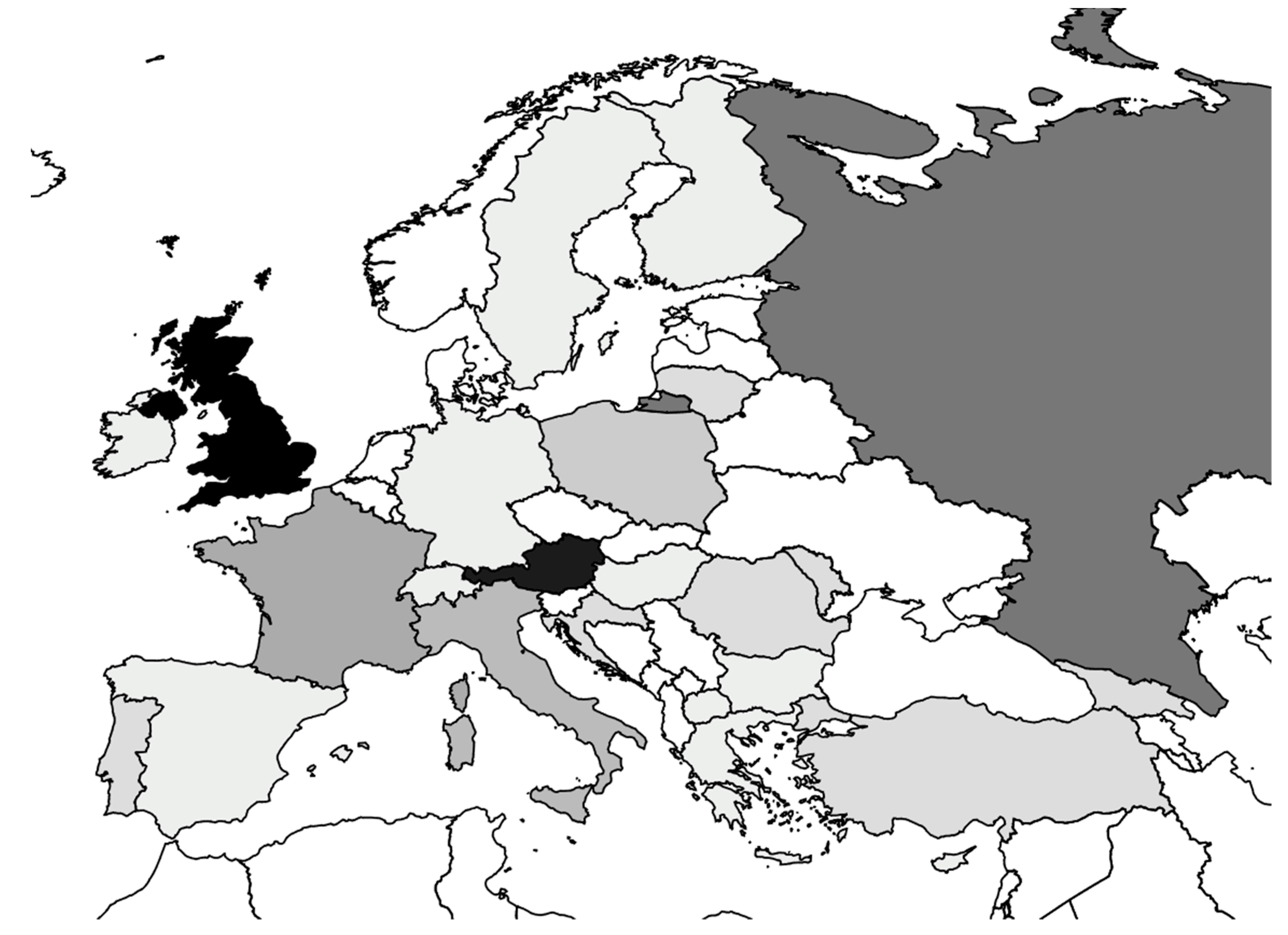

3.1. Countries

3.2. Articles of the European Convention on Human Rights

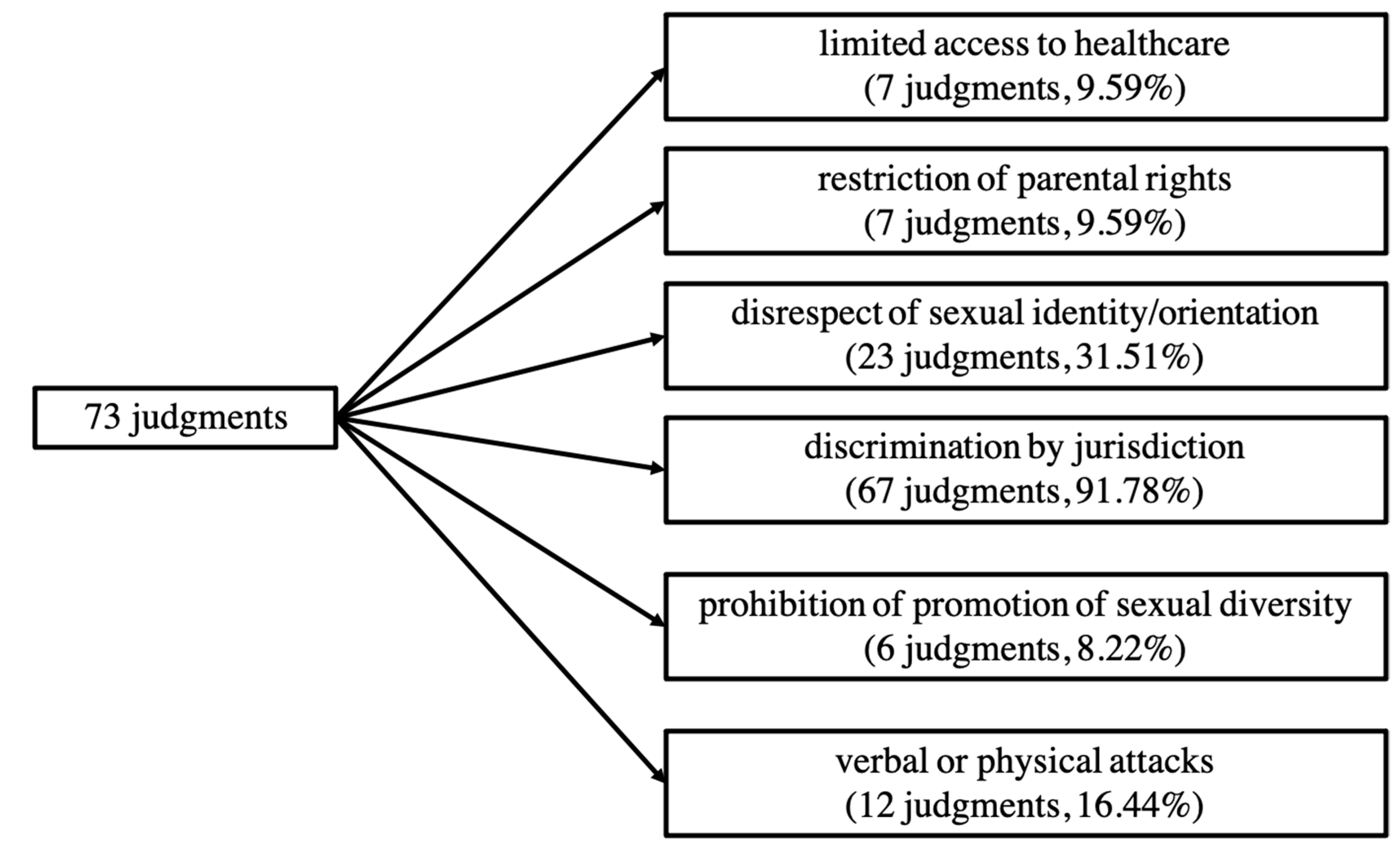

3.3. Categories

3.3.1. Judgments Involving Limited Access to Healthcare

3.3.2. Judgments Involving Discrimination by Restriction of Parental Rights

3.3.3. Judgments Involving Discrimination by the Disrespect of Sexual Identity or Sexual Orientation

3.3.4. Judgments Involving Discrimination by Jurisdiction

3.3.5. Judgments Involving Discrimination by the Prohibition of Promotion of Sexual Diversity

3.3.6. Judgments Involving Discrimination by Verbal or Physical Attacks

4. Discussion

4.1. Cases Involving Limited Access to Healthcare

4.2. Cases Involving All Other Identified Types of Discrimination

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reback, C.J.; Clark, K.; Holloway, I.W.; Fletcher, J.B. Health Disparities, Risk Behaviors and Healthcare Utilization among Transgender Women in Los Angeles County: A Comparison from 1998–1999 to 2015–2016. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 2524–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, A.J.; Hallum-Montes, R.; Nevin, K.; Zenker, R.; Sutherland, B.; Reagor, S.; Ortiz, M.E.; Woods, C.; Frost, M.; Cochran, B.; et al. Determinants of Transgender Individuals’ Well-Being, Mental Health, and Suicidality in a Rural State. Rural Ment. Health 2018, 42, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughto, J.M.W.; Rose, A.J.; Pachankis, J.E.; Reisner, S.L. Barriers to Gender Transition-Related Healthcare: Identifying Underserved Transgender Adults in Massachusetts. Transgender Health 2017, 2, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, S.P.; Lilly, C.L.; Shapiro, R.E.; Kidd, K.M.; Elmo, R.M.; Altobello, R.A.; Vallejo, M.C. Knowledge and Attitudes of Health Care Providers Toward Transgender Patients within a Rural Tertiary Care Center. Transgender Health 2019, 4, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brummett, A.; Campo-Engelstein, L. Conscientious objection and LGBTQ discrimination in the United States. J. Public Health Policy 2021, 42, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puckett, J.A.; Cleary, P.; Rossman, K.; Newcomb, M.E.; Mustanski, B. Barriers to Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Individuals. Sex Res. Soc. Policy 2018, 15, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.S.; Saleh, R.; Kamal, H.; Gillani, M.; Merchant, A.A.H.; Munir, M.M.; Iftikar, H.M.; Shah, Z.; Hussain, M.H.Z.; Azhar, M.K.; et al. The Need for Transgender Healthcare Medical Education in a Developing Country. Adv. Med. Educ. 2020, 11, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, S.; Jamieson, A.; Cross, H.; Nambiar, K.; Llewellyn, C. Medical students’ awareness of health issues, attitudes, and confidence about caring for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender patients: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szél, Z.; Kiss, D.; Török, Z.; Gyarmathy, V.A. Hungarian Medical Students’ Knowledge About and Attitude toward Homosexual, Bisexual, and Transsexual Individuals. J. Homosex. 2020, 67, 1429–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, J.; Choi, B.; Yi, H.; Kim, S.-S. Experiences of and barriers to transition-related healthcare among Korean transgender adults: Focus on gender identity disorder diagnosis, hormone therapy, and sex reassignment surgery. Epidemiol. Health 2018, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, J.P.; Cintulova, M.; Provencio-Vasquez, E.; Rodriguez, A.E.; Cicero, E.C. Transgender women’s satisfaction with healthcare services: A mixed-methods pilot study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020, 56, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Jaramillo, M.; Mendoza, Á.; Acevedo, N.; Forero-Martínez, L.J.; Sánchez, S.M.; Rivillas-García, J.C. How to adapt sexual and reproductive health services to the needs and circumstances of trans people- a qualitative study in Colombia. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, M.; Kerr, S.; Bauerband, L.A.; Koegler, E.; Graves, R. A Qualitative Scoping Review of Transgender and Gender Non-conforming People’s Physical Healthcare Experiences and Needs. Front. Public Health 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Tasa-Vinyals, E.; Gahagan, J. Improving the LGBTQ2S+ cultural competency of healthcare trainees: Advancing health professional education. Can. Med. Educ. J. 2021, 12, e7–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, S.; Kroll, T.; O’Shea, D.; Neff, K. Experiences of transgender and non-binary youth accessing gender-affirming care: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, R.; Gallibois, C.; Coutin, A.; Wright, S. Learning by chance: Investigating gaps in transgender care education amongst family medicine, endocrinology, psychiatry and urology residents. Can. Med. Educ. J. 2020, 11, e19–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, T.; Lee, Y.A.; Damiano, E.A. Do Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals Receive Adequate Gynecologic Care? An Analysis of a Rural Academic Center. Transgender Health 2020, 5, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, J.; Blaszcyk, W.; Täuber, L.; Dekker, A.; Briken, P.; Nieder, T.O. Barriers to Accessing Health Care in Rural Regions by Transgender, Non-Binary, and Gender Diverse People: A Case-Based Scoping Review. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, E.M.; Burgess, C.M. Sexual and Gender Minority Health Care Disparities: Barriers to Care and Strategies to Bridge the Gap. Prim. Care 2021, 48, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Joudeh, L.; Harris, O.O.; Johnstone, E.; Heavner-Sullivan, S.; Propst, S.K. “Little Red Flags”: Barriers to Accessing Health Care as a Sexual or Gender Minority Individual in the Rural Southern United States-A Qualitative Intersectional Approach. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2021, 32, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Crosby, R.A. Social Determinants of Discrimination and Access to Health Care among Transgender Women in Oregon. Transgender Health 2020, 5, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. EU-LGBTI II. A Long Way to Go for LGBTI Equality; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; pp. 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Martínez, J.; Saus-Ortega, C.; Sánchez-Lorente, M.M.; Sosa-Palanca, E.M.; García-Martínez, P.; Mármol-López, M.I. Health Inequities in LGBT People and Nursing Interventions to Reduce Them: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassing, F.; Casanova, T.; Griffin, J.A.; Wood, E.; Stepleman, L. The Effects of Polyvictimization on Mental and Physical Health Outcomes in an LGBTQ Sample. J. Trauma Stress 2021, 34, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flentje, A.; Heck, N.C.; Brennan, J.M.; Meyer, I.H. The relationship between minority stress and biological outcomes: A systematic review. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 43, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendos, L.R.; Botha, K.; Lelis, R.C.; de la Peña, E.L.; Savelev, I.; Tan, D. State-Sponsored Homophobia 2020: Global Legislation Overview Update; ILGA World: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Court of Human Rights. How the Court Works. Available online: https://www.echr.coe.int/Pages/home.aspx?p=court/howitworks&c= (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Democracy and Human Rights. The LGBTI Movement in Cyprus. Available online: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/zypern/15949-20200213.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiam, Z.; Duffy, S.; Gil, M.G.; Goodwin, L.; Patel, N.T.M. Trans Legal Mapping Report 2019: Recognition before the Law; ILGA World: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Foster Skewis, L.; Bretherton, I.; Leemaqz, S.Y.; Zajac, J.D.; Cheung, A.S. Short-Term Effects of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy on Dysphoria and Quality of Life in Transgender Individuals: A Prospective Controlled Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.; Boczek, U.; Bojunga, J. Hormonal Gender Reassignment Treatment for Gender Dysphoria. Dtsch Ärztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Peraza, M.E.; García-Acosta, J.M.; Delgado, N. Gender Identity: The Human Right of Depathologization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCann, E.; Donohue, G.; Brown, M. Experiences and Perceptions of Trans and Gender Non-Binary People Regarding Their Psychosocial Support Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyar, M.; Kubre, M.A.; Collet, S.; Bhaduri, S.; T’Sjoen, G.; Guillamon, A.; Mueller, S.C. Minority Stress and the Effects on Emotion Processing in Transgender Men and Cisgender People: A Study Combining fMRI and Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (1H-MRS). Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E.; Claes, L.; Bouman, W.P.; Witcomb, L.; Arcelus, J. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality in trans people: A systematic review of the literature. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mustanski, B.; Liu, R.T. A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2013, 42, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, M.E.; Gower, A.L.; McMorris, B.J.; Rider, G.N.; Cokeman, E. Emotional Distress, Bullying Victimization, and Protective Factors Among Transgender and Gender Diverse Adolescents in City, Suburban, Town and Rural Locations. J. Rural Health 2019, 35, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, N.S.; Elwy, A.R. The Role of Implementation Science in Reducing Sexual and Gender Minority Mental Health Disparities. LGBT Health 2021, 8, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachankis, J.E.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Bränström, R.; Schmidt, A.J.; Berg, R.C.; Jonas, K.; Pitoňák, M.; Baros, S.; Weatherburn, P. Structural stigma and sexual minority men’s depression and suicidality: A multilevel examination of mechanisms and mobility across 48 countries. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2021, 130, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Articles of the European Convention on Human Rights | Name of the Article | Judgments Involving This Article | Judgments in Which at Least One Violation of This Article Was Found (Either Alone or in Conjunction with Other Articles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Article 3 | Prohibition of torture | n = 11 (15.07%) | n = 8 (10.96%) |

| Article 5 | Right to liberty and security | n = 3 (4.11%) | n = 3 (4.11%) |

| Article 6 | Right to a fair trial | n = 6 (8.22%) | n = 4 (5.48%) |

| Article 8 | Right to respect for private and family life | n = 55 (75.34%) | n = 42 (57.53%) |

| Article 9 | Freedom of thought, conscience and religion | n = 1 (1.37%) | n = 0 |

| Article 10 | Freedom of expression | n = 6 (8.22%) | n = 2 (2.74%) |

| Article 11 | Freedom of assembly and association | n = 9 (12.33%) | n = 8 (10.96%) |

| Article 12 | Right to marry | n = 9 (12.33%) | n = 2 (2.74%) |

| Article 13 | Right to an effective remedy | n = 10 (13.70%) | n = 6 (8.22%) |

| Article 14 | Prohibition of discrimination | n = 57 (78.08%) | n = 33 (45.21%) |

| Article 18 | Limitation on use of restrictions on rights | n = 1 (1.37%) | n = 1 (1.37%) |

| Article 1 of Protocol No 1 | Protection of property | n = 1 (1.37%) | n = 1 (1.37%) |

| Article 1 of Protocol No 12 | General prohibition of discrimination | n = 1 (1.37%) | n = 0 |

| Country | No. of Judgments | Violation of … | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Art. 3 | Art. 5 | Art. 6 | Art. 8 | Art. 10 | Art. 11 | Art. 12 | Art. 13 | Art. 14 | Art. 18 | Art. 1 of Protocol 1 | ||

| United Kingdom | 15 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Austria | 13 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |||||||

| Russia | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 1 | |||

| France | 5 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||

| Italy | 4 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||

| Poland | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Croatia | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Georgia | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Lithuania | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Moldova | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Portugal | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Romania | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Turkey | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Bulgaria | 1 | |||||||||||

| Cyprus | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Finland | 1 | |||||||||||

| Germany | 1 | |||||||||||

| Greece | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Hungary | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Ireland | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Macedonia | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Spain | 1 | |||||||||||

| Sweden | 1 | |||||||||||

| Switzerland | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Main Category | Number (Percentage) of Judgments in the Main Category | Sub-Categories | Number (Percentage) of Judgments in Subcategories | Examples Presented in the Text |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited access to healthcare | n = 7 (9.59%) | Restriction of reimbursement of hormone therapy and/or gender reassignment therapy | n = 1 (14.29%) | Van Kück v. Germany (35968/97) |

| Difficulty to receive hormone therapy and/or gender reassignment surgery due to legal uncertainties | n = 3 (42.86%) | L. v. Lithuania (27527/03) | ||

| Denial of artificial insemination | n = 1 (14.29%) | |||

| Denial of extension of health insurance | n = 1 (14.29%) | |||

| Denial of access to medical doctor | n = 1 (14.29%) | |||

| Restriction of parental rights | n = 7 (9.59%) | Concerning transsexual individual | n = 1 (14.29%) | |

| Concerning homosexual individuals | n = 6 (85.71%) | X and others v. Austria (19019/07 | ||

| Disrespect of sexual identity/orientation | n = 23 (31.51%) | Concerning disrespect of sexual identity | n = 16 (69.57%) | B. v. France (13343/87) |

| Concerning disrespect of sexual orientation | n = 7 (30.43%) | Pajic v. Croatia (68453/13) | ||

| Discrimination by jurisdiction | n = 67 (91.78%) | Concerning transsexual individuals | n = 15 (22.39%) | Christine Goodwin v. the United Kingdom (28957/95) |

| Concerning homosexual individuals | n = 45 (67.16%) | S. L. v. Austria (45330/99) | ||

| Concerning trans- and homosexual individuals | n = 7 (10.45%) | |||

| Prohibition of promotion of sexual diversity | n = 6 (8.22%) | Genderdoc-M v. Moldova (9106/06) | ||

| Verbal or physical attacks | n = 12 (16.44%) | Concerning homosexual individuals | n = 5 (44.44%) | Sabalic v. Croatia (50231/13) |

| Concerning trans- and homosexual individuals | n = 7 (55.56%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skuban, T.; Orzechowski, M.; Steger, F. Restriction of Access to Healthcare and Discrimination of Individuals of Sexual and Gender Minority: An Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights from an Ethical Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052650

Skuban T, Orzechowski M, Steger F. Restriction of Access to Healthcare and Discrimination of Individuals of Sexual and Gender Minority: An Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights from an Ethical Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(5):2650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052650

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkuban, Tobias, Marcin Orzechowski, and Florian Steger. 2022. "Restriction of Access to Healthcare and Discrimination of Individuals of Sexual and Gender Minority: An Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights from an Ethical Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 5: 2650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052650

APA StyleSkuban, T., Orzechowski, M., & Steger, F. (2022). Restriction of Access to Healthcare and Discrimination of Individuals of Sexual and Gender Minority: An Analysis of Judgments of the European Court of Human Rights from an Ethical Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052650