Prevalence of Violence Perpetrated by Healthcare Workers in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

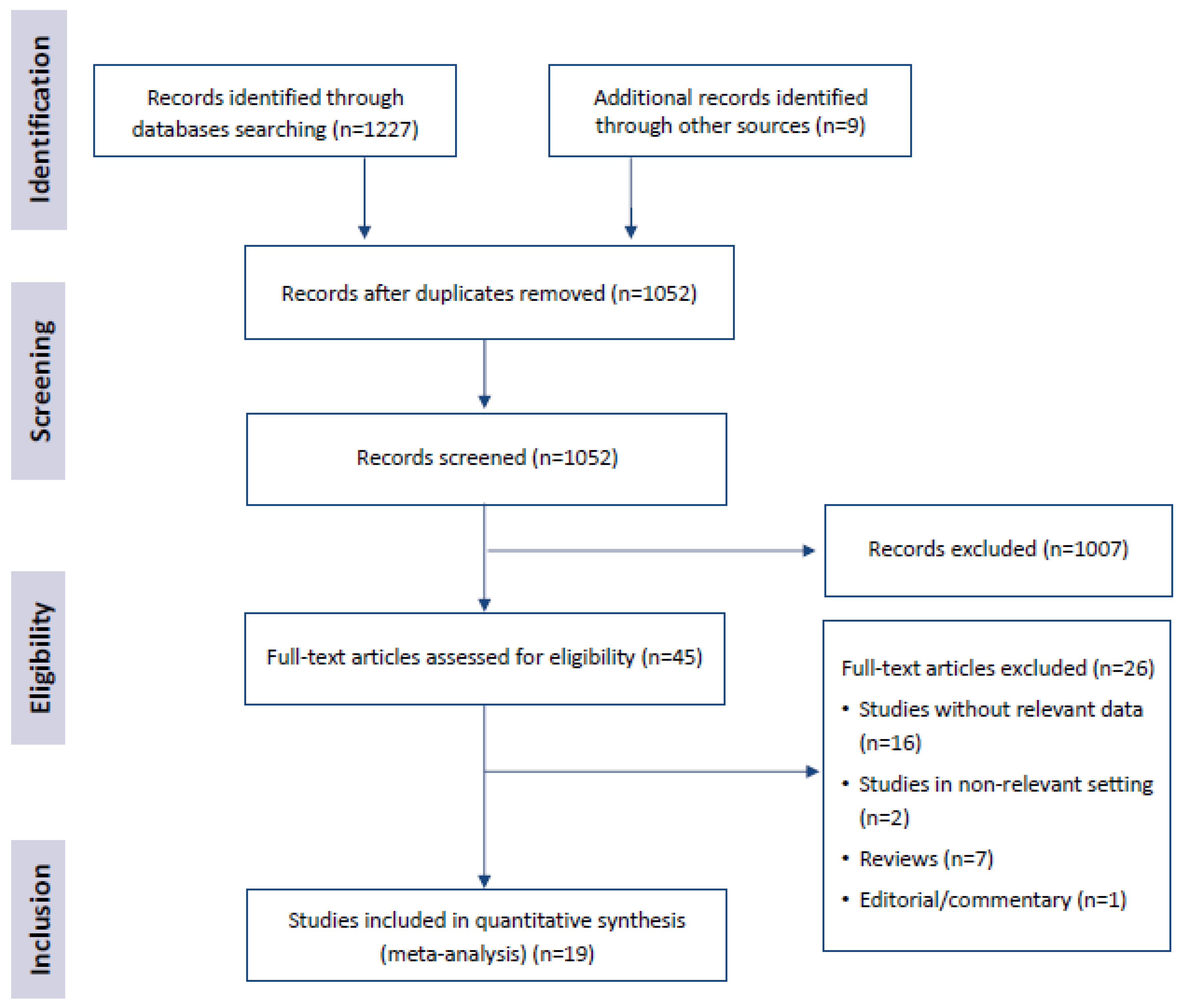

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

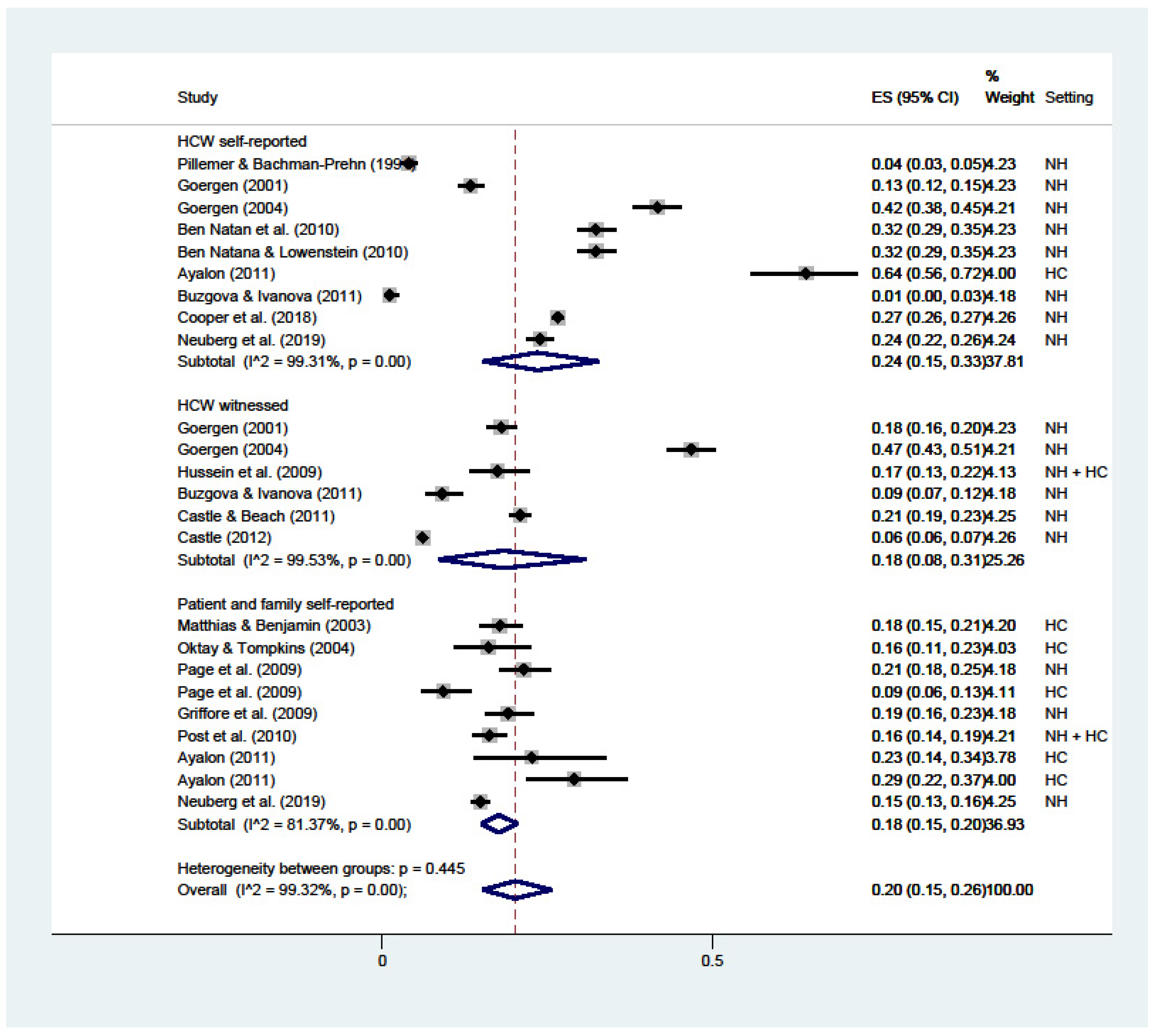

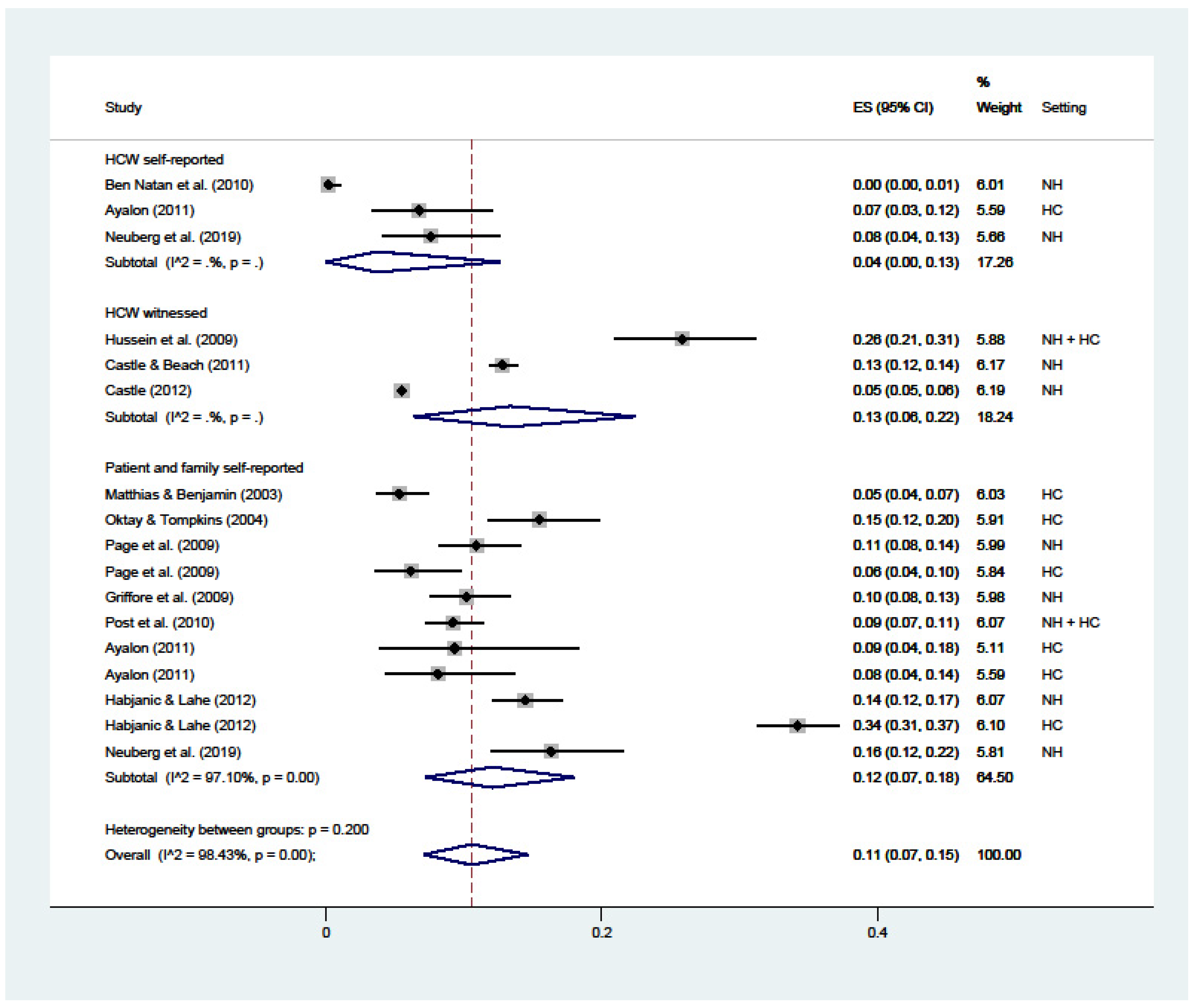

2.4.1. Overall Pooled Prevalence of Violence in LTC

2.4.2. Subgroup Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Violence in Different LTC Settings

3. Results

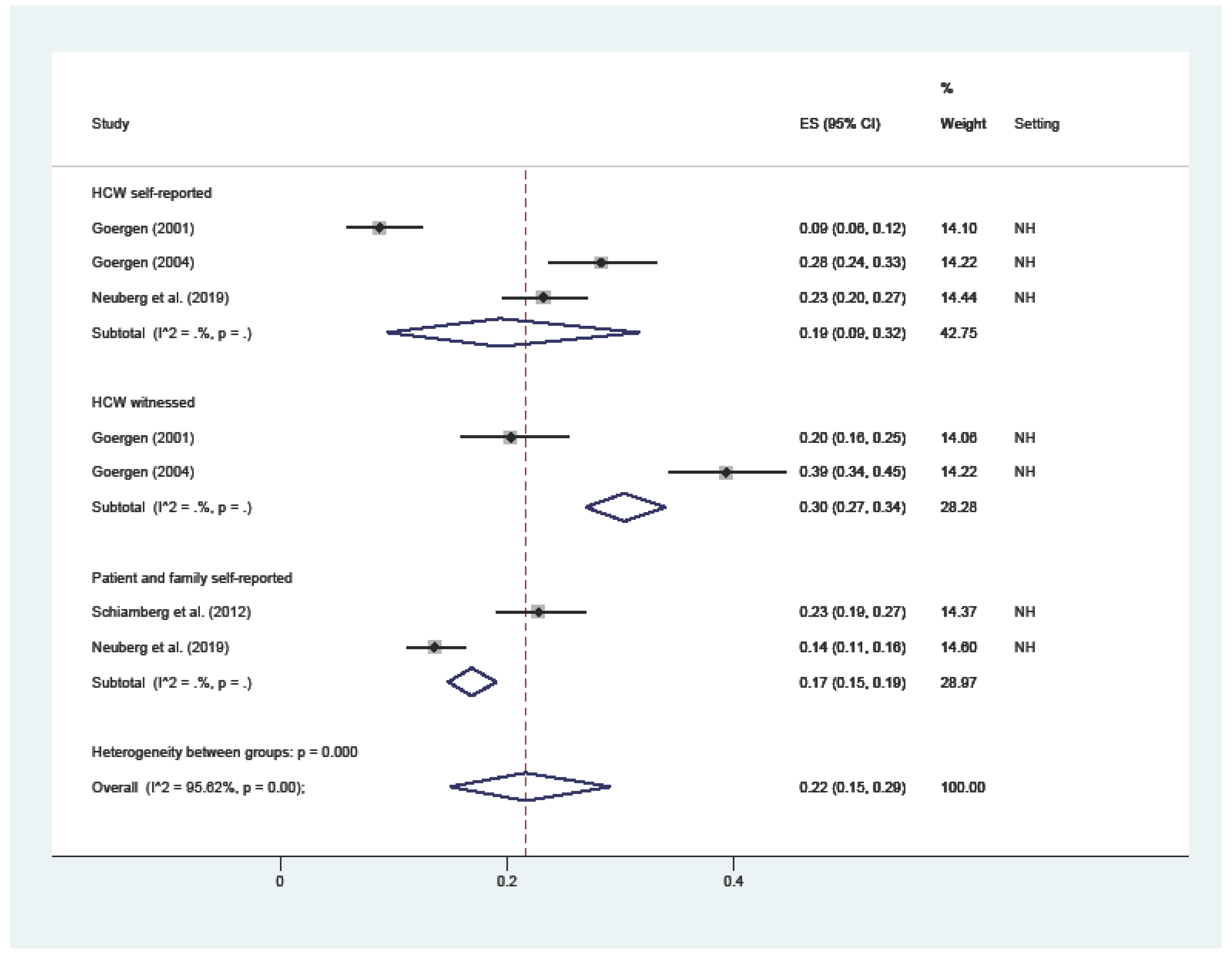

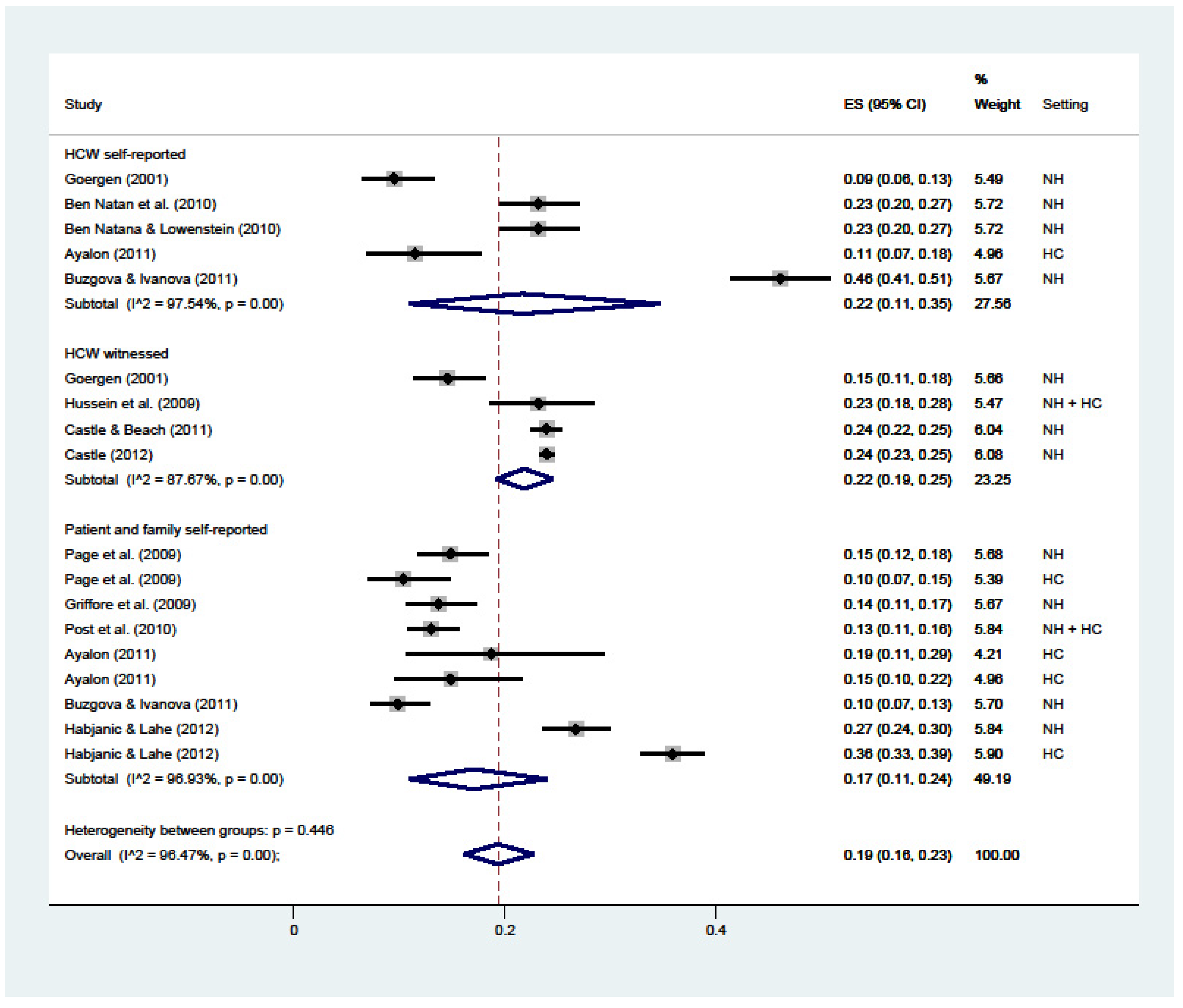

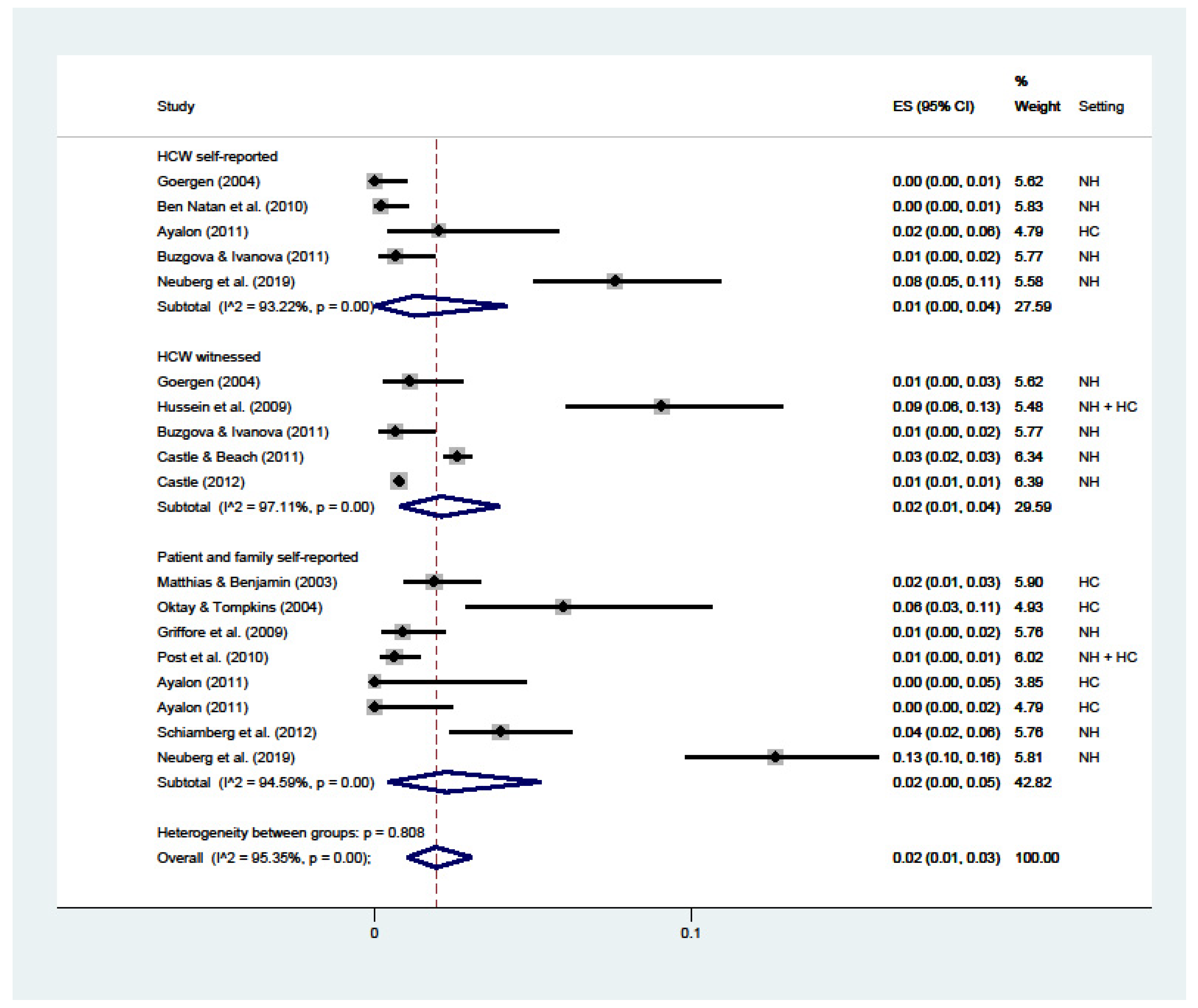

3.1. Prevalence of the Types of Violence in LTC

3.2. Subgroup Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Violence in Different LTC Settings

3.3. Subgroup Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Violence Stratified by Study Quality

3.4. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonald, L.; Beaulieu, M.; Harbison, J.; Hirst, S.; Lowenstein, A.; Bsn, E.P.; Wahl, J. Institutional Abuse of Older Adults: What We Know, What We Need to Know. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2012, 24, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiamberg, L.B.; Barboza, G.G.; Oehmke, J.; Zhang, Z.; Griffore, R.J.; Weatherill, R.P.; Von Heydrich, L.; Post, L.A. Elder Abuse in Nursing Homes: An Ecological Perspective. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2011, 23, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkur, S.; McDaid, D.; Maresso, A. Meeting the Challenge of Ageing and Long-Term Care. Eurohealth 2011, 17, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, N.J. Basics of the U.S. Health Care System, 4th ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, D.; Wood, S.; Mitis, F.; Bellis, M.; Penhale, B.; Iborra Marmolejo, I.; Lowenstein, A.; Manthorpe, G.; Karki, F.U. European Report on Preventing Elder Matreatment; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer, K.; Burnes, D.; Riffin, C.; Lachs, M.S. Elder Abuse: Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Prevention Strategies. Gerontologist 2016, 56, S194–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yon, Y.; Mikton, C.R.; Gassoumis, Z.D.; Wilber, K.H. Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e147–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yon, Y.; Ramiro-Gonzalez, M.; Mikton, C.R.; Huber, M.; Sethi, D. The prevalence of elder abuse in institutional settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.; Jones, L.; Wood, S.; Bates, G.; Eckley, L.; McCoy, E.; Mikton, C.; Shakespeare, T.; Officer, A. Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet 2012, 379, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Bellis, M.; Wood, S.; Hughes, K.; McCoy, E.; Eckley, L.; Bates, G.; Mikton, C.; Shakespeare, T.; Officer, A. Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet 2012, 380, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clari, M.; Conti, A.; Scacchi, A.; Scattaglia, M.; Dimonte, V.; Gianino, M.M. Prevalence of Workplace Sexual Violence against Healthcare Workers Providing Home Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.R.; Guo, G.; Kim, H. Elder Mistreatment in U.S. Residential Care Facilities: The Scope of the Problem. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2013, 25, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barendregt, J.J.; Doi, S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Norman, R.E.; Vos, T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2013, 67, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, W.Y.; Hairi, N.N.; Othman, S.; Francis, D.P.; Baker, P.R. Interventions for preventing abuse in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, 1–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Toronto Declaration on the Global Prevention of Elder Abuse; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, S.; Flaherty, J.H. Elder Abuse and Neglect in Long-Term Care. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2005, 21, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-J. Psychological abuse and its characteristic correlates among elderly Taiwanese. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2006, 42, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Wang, J.-J.; Yen, M.; Liu, T.-T. Educational support group in changing caregivers’ psychological elder abuse behavior toward caring for institutionalized elders. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2008, 14, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loghmani, L.; Borhani, F.; Abbaszadeh, A. Factors Affecting the Nurse-Patients’ Family Communication in Intensive Care Unit of Kerman: A Qualitative Study. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 3, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Lev, S.; Green, O.; Nevo, U. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions designed to prevent or stop elder maltreatment. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindert, J.; de Luna, J.; Torres-Gonzales, F.; Barros, H.; Ioannidi-Kopolou, E.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Stankunas, M.; Macassa, G.; Soares, J.F.J. Abuse and neglect of older persons in seven cities in seven countries in Europe: A cross-sectional community study. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodolska, A.; Parnicka, A.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Grodzicki, T. Exploring Elder Neglect: New Theoretical Perspectives and Diagnostic Challenges. Gerontology 2019, 60, e438–e448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.Q. Elder Abuse: Systematic Review and Implications for Practice. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 1214–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmedal, W.; Iversen, M.H.; Kilvik, A. Sexual Abuse of Older Nursing Home Residents: A Literature Review. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2015, 2015, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schneider, D.C.; Li, X. Sexual Abuse of Vulnerable Adults: The Medical Director’s Response. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2006, 7, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanrahan, N.P.; Burgess, A.W.; Gerolamo, A.M. Core Data Elements Tracking Elder Sexual Abuse. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2005, 21, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estebsari, F.; Dastoorpoor, M.; Mostafaei, D.; Khanjani, N.; Khalifehkandi, Z.R.; Foroushani, A.R.; Aghababaeian, H.; Taghdisi, M.H. Design and implementation of an empowerment model to prevent elder abuse: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, ume 13, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.G.; O’Neill, D. Prevention of elder abuse. Lancet 2011, 377, 2005–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesen, M.; LoGiudice, D. Elder abuse: A systematic review of risk factors in community-dwelling elders. Age Ageing 2013, 42, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acierno, R.; Hernandez, M.A.; Amstadter, A.B.; Resnick, H.S.; Steve, K.; Muzzy, W.; Kilpatrick, D.G. Prevalence and Correlates of Emotional, Physical, Sexual, and Financial Abuse and Potential Neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Beck, T.; Simon, M.A. Loneliness and Mistreatment of Older Chinese Women: Does Social Support Matter? J. Women Aging 2009, 21, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J. Living with ‘Hwa-byung’: The psycho-social impact of elder mistreatment on the health and well-being of older people. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 18, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Simon, M.A. Association between Reported Elder Abuse and Rates of Admission to Skilled Nursing Facilities: Findings from a Longitudinal Population-Based Cohort Study. Gerontology 2013, 59, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schofield, M.J.; Powers, J.R.; Loxton, D. Mortality and Disability Outcomes of Self-Reported Elder Abuse: A 12-Year Prospective Investigation. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.L.; Hafemeister, T.L. Risk Factors Associated With Elder Abuse: The Importance of Differentiating by Type of Elder Maltreatment. Violence Vict. 2011, 26, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiamberg, L.B.; Gans, D. Elder Abuse by Adult Children: An Applied Ecological Framework for Understanding Contextual Risk Factors and the Intergenerational Character of Quality of Life. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2000, 50, 329–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L. A triadic perspective on elder neglect within the home care arrangement. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 811–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, K.L.; Nguyen, A.L.; Meurer, L.N. The Effectiveness of Educational Programs to Improve Recognition and Reporting of Elder Abuse and Neglect: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2011, 23, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rn, J.M.D.; Rn, M.L.M.; Jogerst, G.J. Elder Abuse Research: A Systematic Review. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2011, 23, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeg, J.; Fear, J.; Hutchison, B.; Macmillan, H.; Bolan, G. A Systematic Review of Interventions for Elder Abuse. J. Elder Abus. Negl. 2009, 21, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhang, A.; Wang, K. The Effectiveness of Psychosocial Interventions for Elder Abuse in Community Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 679541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, T.; Peters, C.; Nienhaus, A.; Schablon, A. Interventions for Workplace Violence Prevention in Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author(s), Year | Country | Population | Setting | Sample | Type of Violence | Data Source | Quality Assessment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Abuse | Physical Restraint | Verbal Abuse | Psychological Abuse | Sexual Abuse | Neglect | Financial Abuse | |||||||

| Ayalon 2011 | Israel | Older persons | Home care | 371 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | HCWs S-R; Patient or family S-R | 6/9 (fair) | ||

| Ben Natan et al., 2010 | Israel | Older persons | Nursing home | 510 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | HCWs S-R | 8/9 (good) | ||

| Ben Natan & Lowenstein 2010 | Israel | Older persons | Nursing home | 510 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | HCWs S-R | 7/9 (fair) | ||||

| Buzgova & Ivanova 2011 | Czech Republic | Older persons | Nursing home | 942 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | HCWs S-R; Witnessed; Patient or family S-R | 8/9 (good) | |||

| Castle 2012 | USA | Older persons | Nursing home | 3433 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Witnessed | 6/9 (fair) | |

| Castle & Beach 2011 | USA | Older persons | Nursing home | 832 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Witnessed | 6/9 (fair) | |

| Cooper et al., 2018 | UK | Dementia | Nursing home | 1544 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | HCWs S-R | 8/9 (good) | ||||

| Goergen 2001 | Germany | Older persons | Nursing home | 80 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | HCWs S-R; Witnessed | 4/9 (poor) | ||

| Goergen 2004 | Germany | Older persons | Nursing home | 361 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | HCWs S-R; Witnessed | 4/9 (poor) | |||

| Griffore et al., 2009 | USA | Older persons | Nursing home | 452 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Patient or family S-R | 4/9 (poor) | |

| Habjanic & Lahe 2012 | Slovenia | Older persons | Nursing home and home care | 300 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Patient or family S-R | 5/9 (fair) | ||||

| Hussein et al., 2009 | UK | Vulnerable adults | Nursing home and home care | 298 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Witnessed | 3/9 (poor) | ||

| Matthias & Benjamin 2003 | USA | Vulnerable adults | Home care | 584 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Patient or family S-R | 6/9 (fair) | ||

| Neuberg et al., 2019 | Croatia | Older persons | Nursing home | 416 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | HCWs S-R; Patient or family S-R | 5/9 (fair) | |

| Oktay & Tompkins 2004 | USA | Adults with disabilities | Home care | 84 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Patient or family S-R | 4/9 (poor) | ||

| Page et al., 2009 | USA | Older persons | Nursing home and home care | 718 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Patient or family S-R | 4/9 (poor) | ||

| Pillemer & Bachman-Prehn 1991 | USA | Older persons | Nursing home | 577 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | HCWs S-R | 8/9 (good) | ||||

| Post et al., 2010 | USA | Older persons | Nursing home and home care | 816 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Patient or family S-R | 6/9 (fair) | |

| Schiamberg et al., 2012 | USA | Older persons | Nursing home | 452 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Patient or family S-R | 6/9 (fair) | ||||

| S-R: self-reported | |||||||||||||

| Physical Abuse | Physical Restraint | Verbal Abuse | Psychological Abuse | Sexual Abuse | Neglect | Financial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing home | 0.09 (0.05–0.15) | 0.19 (0.09–0.32) | 0.25 (0.15–0.38) | 0.24 (0.12–0.39) | 0.01 (0.00–0.05) | 0.19 (0.12–0.28) | 0.01 (0.00–0.02) |

| Home care | 0.03 (0.01–0.09) | / | / | 0.11 (0.07–0.35) | 0.02 (0.00–0.06) | 0.64 (0.56–0.72) | 0.07 (0.03–0.12) |

| Physical Abuse | Physical Restraint | Verbal Abuse | Psychological Abuse | Sexual Abuse | Neglect | Financial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing home | 0.20 (0.07–0.37) | 0.30 (0.27–0.34) | 0.34 (0.25–0.44) | 0.21 (0.18–0.25) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.18 (0.08–0.33) | 0.07 (0.06–0.07) |

| Home care | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| Physical Abuse | Physical Restraint | Verbal Abuse | Psychological Abuse | Sexual Abuse | Neglect | Financial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing home | 0.04 (0.03–0.07) | 0.17 (0.15–0.19) | 0.21 (0.07–0.39) | 0.16 (0.09–0.24) | 0.05 (0.00–0.13) | 0.18 (0.14–0.23) | 0.13 (0.10–0.16) |

| Home care | 0.04 (0.01–0.09) | / | 0.11 (0.03–0.23) | 0.19 (0.07–0.31) | 0.01 (0.00–0.04) | 0.18 (0.12–0.25) | 0.12 (0.03–0.25) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Conti, A.; Scacchi, A.; Clari, M.; Scattaglia, M.; Dimonte, V.; Gianino, M.M. Prevalence of Violence Perpetrated by Healthcare Workers in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042357

Conti A, Scacchi A, Clari M, Scattaglia M, Dimonte V, Gianino MM. Prevalence of Violence Perpetrated by Healthcare Workers in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042357

Chicago/Turabian StyleConti, Alessio, Alessandro Scacchi, Marco Clari, Marco Scattaglia, Valerio Dimonte, and Maria Michela Gianino. 2022. "Prevalence of Violence Perpetrated by Healthcare Workers in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042357

APA StyleConti, A., Scacchi, A., Clari, M., Scattaglia, M., Dimonte, V., & Gianino, M. M. (2022). Prevalence of Violence Perpetrated by Healthcare Workers in Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042357