Implementation of Breastfeeding Policies at Workplace in Mexico: Analysis of Context Using a Realist Approach

Abstract

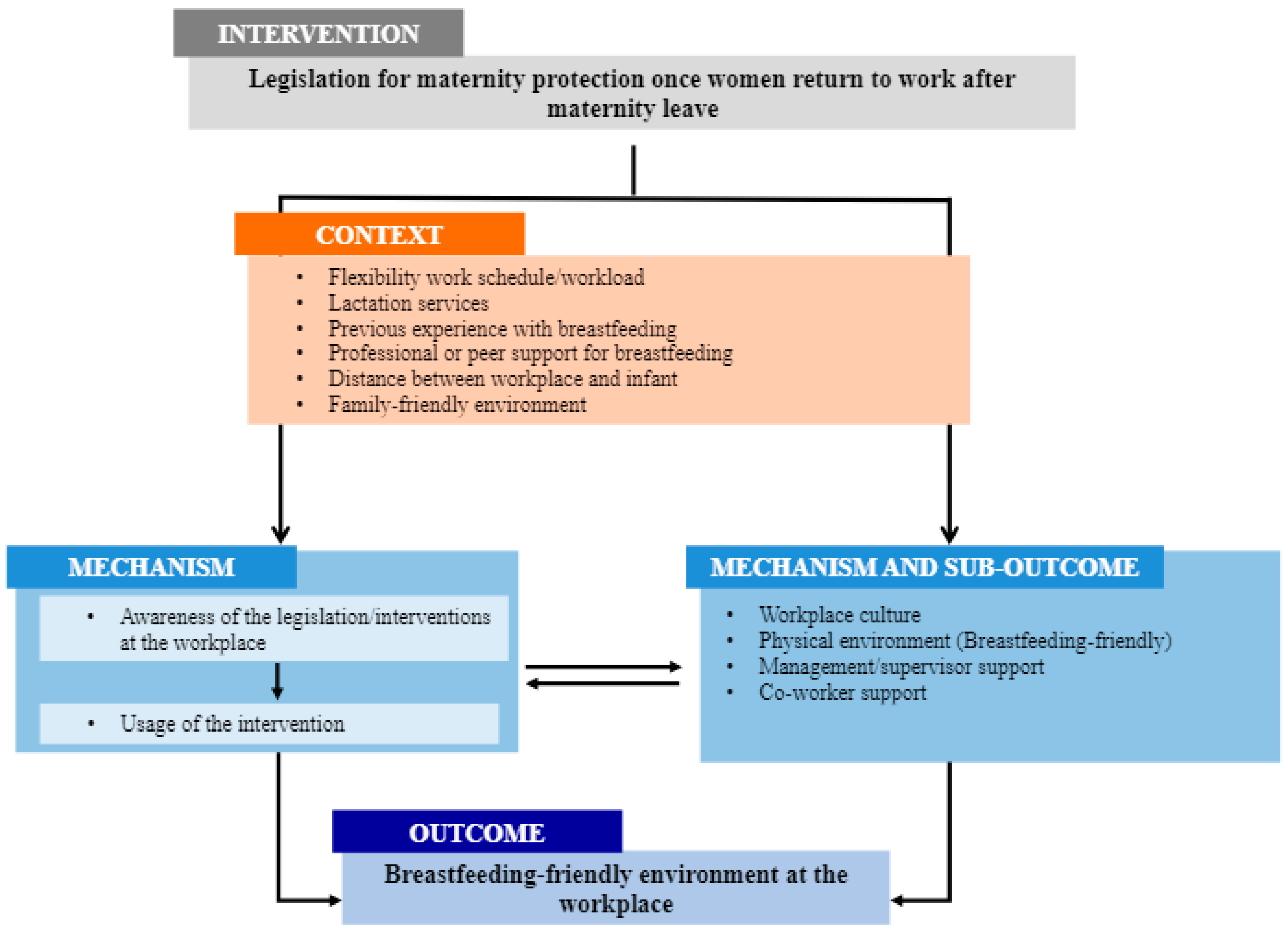

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Settings

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Qualitative Thematic Analysis

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Context

3.1.1. Flexibility Work Schedule/Workload

[Schedule flexibility] “… Yes, they gave me a time to choose, you know that the law says that it is a half hour to breastfeed, they gave me the time to choose whether to come in late or leave early, because here you can’t take your half hour to go and breastfeed your child, nor is there a space for them to bring the baby to you. I know there are places that have a lactation room, and you can go to express milk during those half hours. So, I would leave early, however, I can tell you that there were days that they would not let me leave at my time. The work that our area has sometimes did not allow it…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Chihuahua, [B02])

[No schedule flexibility] “… No, it was normal, I didn’t have that thing about leaving earlier or coming in later. It was a normal schedule…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Merida, [B03])

[Schedule flexibility] “… Working mothers can enjoy the reduction of their working day for breastfeeding period once their maternity leave is over […] through a request they make directly to their immediate supervisor where they present the schedules that best suit them for the attendance of their child, […] and she explains to us if she wants to arrive an hour later than when she starts work, if she wants to take two hours for lunch or if she prefers to leave an hour earlier than her working time, as she decides, to breastfeed her child. In addition, as many times as she requires during her work day in the space we have designated for breast milk expression […] she can use them as long and as often as she needs to.…”(Manager and HR personnel, Guadalajara, [RRHH02])

3.1.2. Lactation Services

“… Once they come off maternity leave, we are aware of when they return because at that time we contact them and talk to them about breastfeeding, we give them a talk on breastfeeding, benefits for them, for the baby, etc., and we provide follow-up, we explain to them what the breastfeeding period is and after that period, if they need more days, how they should request it, because they can request more days than the period that is normally given in the workplace. What else? She is monitored every month to see if there is no problem during lactation, if so, she is referred…”(Manager and HR personnel, Mérida, [RRHH])

“…Mmm yes, I tell you, the flexible schedule, and also many people come to talk to us about everything related to health, maternity and baby…”(Male employees, Chihuahua, [H02])

3.1.3. Previous Experience with BF and Professional or Peer Support for BF

[No support] “…Yes, he was hungry, well, you could see it. Even when I extracted my milk, I had very little. Besides, with the cesarean section it was very tiring to breastfeed in one position and I could not tolerate the pain in my back, and she did not want to get off the breast, so I decided to help myself with formula from the beginning…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Chihuahua, [B01])

[No support] “…Yes, in fact, at the beginning it was only breast milk and then when I was getting ready to go back to work, I had to combine formula with breastfeeding, that’s how it was for both children…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Chihuahua, [B03])

[Success with BF] “… The first one, the truth is, with the first one I didn’t work, and I was at home, and I was able to give him milk for almost two years. With this baby, he is exactly one year and two months old, I continue to breastfeed him when I come home from work and then at night, he continues to drink something…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Mérida, [B01])

[Success with BF] “…My mom, with my first baby. With my first baby I learned many things, my mom showed me, she bought me the breast pump, I mean, a woman’s body is wonderful because I didn’t even have to fight to breastfeed, I always had enough milk, always, always, always, to this day. So, I was learning by myself and with, well, my mother’s workplace. And now that my second baby was born, well, I was released on September 29, by October 2 I was already doing my milk bank and, practically, you learn as you go along…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Chihuahua, [B04])

3.1.4. Distance between Workplace and Infant

[Enabling factor] “… I took the breastfeeding hour half an hour before going to work and I left half an hour before my work schedule. I also have two hours for lunch, I live very close so I would go home, that also helped me…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Mérida, [B01])

[Barrier] “… However, now an hour or two away, because she’s not going to breastfeed the boy or the girl, she’s not going to be able to go home [in such a short time] …”(HR personnel, Guadalajara [RRHH01]

[Enabling] “… So, yes, it should be the right to ask for a lactation room so that you can do it, but if we go to those points, we as a clinic would ask for a lactation room or a daycare because I think the daycare would be easier […] you being here working, “you know what? I feel that my breasts are full” that the clinic can provide us, what would it be? half an hour or an hour to be able to go (to the daycare), give milk to the baby and come back […] They give you your baby, you are in contact with him, seeing that he is well, you give him his two feedings. You are happy, you are not uncomfortable, the baby is full, and you go on with your work. That’s what it should really be, right? but well… it’s fair to dream…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Mérida, [B04])

[Enabling] “… it means that the workplace has to help you as a woman to continue breastfeeding […] give them an hour so that they can go out, or provide them a lactation room and a refrigerator so that they can extract their milk […] because it would be strange in the bathroom, wouldn’t it? […] it would be weird, wouldn’t it? even for hygiene reasons. Now there are workplaces that even have a daycare downstairs, you can go up and down. So, yes, it is more like trying to invite workplaces to take more care of their women, and of the fathers too, because there are fathers who are very supportive of breastfeeding at work…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Chihuahua, [B07])

3.2. Mechanism

3.2.1. Awareness about Maternity Protection Legislations and Interventions Promoting and Protecting BF in the Workplace

[Unawareness of workplace policies] “… Well, I don’t see…I haven’t seen in my department that they tell them anything, on the contrary, they give them support in that sense, that, for example, they work a period of eight hours, right, the working day, and they give them the possibility of leaving an hour earlier to be able to exercise it…”(Male employees, Merida, [H01])

[Unawareness of workplace policies] “… (was asked if she had read or been told that it is a woman’s right to have breastfeeding protected and supported in the workplace) I didn’t know that [laughs], I hadn’t heard anything…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Chihuahua, [B01])

[Unawareness of workplace policies] “… Well, not directly by the workplace, as I said before […] it is possible for women to take some time to extract their milk, but I don’t know the workplace policy…”(Male employees, Chihuahua, [H03])

[Promotion by workplaces] “… No, in fact, all the staff is kept informed that the lactation room has been relocated, and not only for the internal staff or for the internal clients who are our employees, but also in case it is necessary for the guests, which has already happened once a couple of years ago. It is important that they are aware so that if someone asks them, they have the information to be able to say: “yes, we have a lactation room in the workplace, you can use it”, that’s why it is constantly maintained…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Guadalajara, [B02])

3.2.2. Usage of the Intervention

[Usage of intervention] “… I would think that about five women have used the lactation room more or less. This year there were literally about five, but because of COVID it has not been used […] I had a nutritionist in my team and this year she got relief from her baby and was in quarantine, she wasn’t able to use the lactation room either, the one who was able to use it was a previous employee I had and she did use it […] However, yes, if they are given the opportunity to have their breastfeeding times or have a flexible schedule, they try to use the lactation room…”(Manager and HR personnel, Monterrey, [RRHH01])

[Usage of intervention] “… Yes, of course they can use it without any problem, remember that they also have their half hours […] in the end it is their decision, one girl was out because she was considered vulnerable because she was breastfeeding, so when she returned she had two months left and the agreement was that she should leave an hour earlier, but, if she decides, she can go and use the lactation room without any problem, in fact, there is no one who questions this issue, there is only a record…”(Manager and HR personnel, Monterrey, [RRHH02]

3.3. Mechanism and Sub-Outcome

3.3.1. BF Culture in the Workplace (Workplace Culture)

[Perception that the number of potential users is limited] “… Well, I don’t know how… no, I don’t know. I mean, I feel that time has passed for me, I was fine, I don’t have a complaint, so, I don’t think there are that many of us who have children, so, if the question is whether I think it is necessary, I really don’t. Outside, for example, a clothing manufacturing plant, where most of them are women, maybe yes…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Chihuahua, [B03])

[Perception that the number of potential users is limited] “… (was asked if a lactation room is necessary) Well, if our maternity rate were higher, I think it would be necessary, it would definitely be a yes, we would be thinking about having a lactation room, but our rate is so low that it would be a facility, an useless space that we wouldn’t use…”(Manager and HR personnel, Chihuahua, [RRHH01])

[(lack) Incentives enabling BF-friendly environment in the workplace] “… We have talked to managers, they tell you that the initiative is very cool, but they don’t call you back; when you go back to “bother” them, so to speak, one of the things they tell you is that “ups!, I have to submit this project for approval because it costs, if it were a project that did not cost anything there would be no problem, I would give the green light, but it is an initiative that costs because if I do not have the space, I have to build it and if I have it, I have to enable it”…”(Manager and HR personnel, Mérida, [RRHH])

[(lack) Incentives enabling BF-friendly environment in the workplace] “…our main duty is the academy, we need office spaces for teachers, we need classrooms for our students… a series of priorities have been generated, that is why, it seems to me, that the lactation room is taking shape so far…”(Manager and HR personnel, Guadalajara, [RRHH01])

[Importance of a BF-friendly environment in the workplace] “… Well, I think it is very important, because in addition to the fact that mothers do not feel included, in terms of the compatibility of work and family life, I believe that in the sense of belonging to the workplace. It has favored the work environment and moms feel more accepted. The truth is that it was really appreciated both by the mothers and even by male workers. They told us that it was good that we had this space because later they realized that their female colleagues were suffering in the offices, they would go into a meeting room, so they did not have this decent and private space for milk extraction. So, I think that was the main benefit, that they felt confident and the environment among the working mothers was favorable…”(Manager and HR personnel, Guadalajara, [RRHH02])

[Incentives enabling BF-friendly environment in the workplace] “… They let us know that there was another (recognition) called “Family Responsible Company”, and within the guidelines, because we were already giving courses on breastfeeding, we were providing information and training, we were explaining to people the importance of this, but we did not have a space as such to provide support to a person who needed it. So, when we looked into this recognition, we realized that one of the things they asked us to do was to have a lactation room, and we really liked the idea because we had already thought of something like that, but the idea was not quite ready. The Ministry gave us all the guidelines to put it in an orderly manner and give it that formal protocol…”(Male employees, Guadalajara, [H01])

[Incentives enabling a BF-friendly environment in the workplace] “… No, no, not at all, because it is properly stipulated. In fact, we are certified by the Equality Norm where this certificate supports us, allows us to disseminate, to promote spaces and, above all, to raise awareness among managers that they should provide facilities for working mothers, since this is a right for children, so what we promote is the right to breastfeed their children…”(Manager and HR personnel, Guadalajara, [RRHH02])

3.3.2. Physical Environment

[No physical space] “… I extracted myself here, but since there is no lactation room, I regularly went to the bathroom, but I didn’t keep the milk, I threw it away, it was just to continue producing…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Chihuahua, [B01])

[No physical space] “… Well, there are other foods [in the fridge], the truth is that there were occasions when I kept it [the breastmilk] in there [in the fridge], but I don’t know. I didn’t have the confidence to give it [the breastmilk] to him because the fridge is really public…I usually threw it away [the breastmilk] …”(Female employee, Mérida, [B01])

[Available physical space] “… Look, when it was my first delivery, I extracted in the nurses station. In fact, the nurse was there in front. So, it was not very practical because if someone wanted to come in or if there was someone sick and you were in the back extracting milk, wasn’t it? With the second baby there was already a specific space, then there were chairs, there was air conditioning, there were all the conditions, there was a logbook, stereo, you could play music, there was an instruction manual, there was a refrigerator, there was everything. […] So, in the first one, although there was space, it was a bit uncomfortable; in the second one everything was very easy, everything was close at hand, everything was clean, everything was new and, to tell the truth, it was much easier…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Guadalajara, [B01])

3.3.3. Management/Supervisor Support

[Inadequate support] “… No, in fact, this subject had not been mentioned to me and I had to mention it to my boss […] because I was coming, I had already returned from my maternity leave, and I had been going out late for a week. I told him “I think that by law I have a provision or a benefit as a worker, I don’t know if it is half an hour or an hour, in different workplaces they work it differently”, and he said “but it is not by law or yes?”, and I said “Yes, I think it is by law”, and I had to make him a copy of the law and I sent it to him by WhatsApp so he could read it and he said “well, you can take the half hour”…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Mérida, [B07])

[Inadequate support] “…I lost my maternity leave because I gave birth early, so it was only a month and then I started to go to work. In my previous job I was supposed to leave early to breastfeed, but it was very complicated, it was not easy because there was always demanding work. The boss was demanding and then there was no place where you could extract your milk and store it. So, no, they didn’t have those conditions…”(Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries, Chihuahua, [B16])

3.3.4. Co-Worker Support

[Perceived support] “… since we have become familiar with the fact that it is something normal, we all accept the decision, if a colleague is at a work center, we support her or we can solve the details before she arrives. In the event that she has to leave early, we all try to do the work that will be done in the absence of this person…”(Male employees, Merida, [H03])

[Inadequate support] “… What I have perceived, but we have not surveyed, there are people who are bothered by the fact that women leave earlier because they consider that they are burdened with too much work, but honestly they are a couple of isolated comments, the others do not even mention it, I don’t think they even have it in mind…”(Manager and HR personnel, Chihuahua, [RRHH01])

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walters, D.D.; Phan, L.T.H.; Mathisen, R. The cost of not breastfeeding: Global results from a new tool. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, P.H. Social Justice at the Core of Breastfeeding Protection, Promotion and Support: A Conceptualization. J. Hum. Lact. 2018, 34, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. State of the World’s Children 2019: Children, Food and Nutrition; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–258. ISBN 9789280650037. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/63016/file/SOWC-2019.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- World Health Organization; UNICEF. Acceptable Medical Reasons for Use of Breast-Milk Substitutes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24809113 (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Rollins, N.C.; Bhandari, N.; Hajeebhoy, N.; Horton, S.; Lutter, C.K.; Martines, J.C.; Piwoz, E.G.; Richter, L.M.; Victora, C.G. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 2016, 387, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, P.A.R.; Vaz, J.S.; Maia, F.S.; Baker, P.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Piwoz, E.; Rollins, N.; Victora, C.G. Rates and time trends in the consumption of breastmilk, formula, and animal milk by children younger than 2 years from 2000 to 2019: Analysis of 113 countries. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Castell, L.D.; Unar-Munguía, M.; Quezada-Sánchez, A.D.; Bonvecchio-Arenas, A.; Rivera-Dommarco, J. Situación de las prácticas de lactancia materna y alimentación complementaria en México: Resultados de la Ensanut 2018–2019. Salud Publica Mex. 2020, 62, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González de Cosío, T.; Escobar-Zaragoza, L.; González-Castell, L.D.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.Á. Prácticas de alimentación infantil y deterioro de la lactancia materna en México TT—Infant feeding practices and deterioration of breastfeeding in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2013, 55, S170–S179. Available online: http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0036-36342013000800014 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Vilar-Compte, M.; Hernández-Cordero, S.; Ancira-Moreno, M.; Burrola-Méndez, S.; Ferre-Eguiluz, I.; Omaña, I.; Pérez Navarro, C. Breastfeeding at the workplace: A systematic review of interventions to improve workplace environments to facilitate breastfeeding among working women. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unar-Munguía, M.; Lozada-Tequeanes, A.L.; González-Castell, D.; Cervantes-Armenta, M.A.; Bonvecchio, A. Breastfeeding practices in Mexico: Results from the National Demographic Dynamic Survey 2006–2018. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Business Case for Breastfeeding. 2018. Available online: https://www.womenshealth.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-home-work-and-public/breastfeeding-and-going-back-work/business-case (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Heymann, J.; Sprague, A.R.; Nandi, A.; Earle, A.; Batra, P.; Schickedanz, A.; Chung, P.J.; Raub, A. Paid parental leave and family wellbeing in the sustainable development era. Public Health Rev. 2017, 38, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- UNICEF Maternity and Paternity in the Workplace in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Review of National Policies for Paternity and Maternity Leave and Support to Breastfeeding in the Workplace Executive Summary. 2020. Available online: www.ipcig.org (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Secretaría de Gobernación: Artículo 123 Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (Ministry of the Government: Article 123 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States). 2014. Available online: http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/Constitucion/articulos/123.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión Ley Federal del Trabajo (Chamber of Deputies of the H. Congress of the Union Federal Labor Law). 2015. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/156203/1044_Ley_Federal_del_Trabajo.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Litwan, K.; Tran, V.; Nyhan, K.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. How do breastfeeding workplace interventions work?: A realist review. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Westhorp, G.; Greenhalgh, J.; Manzano, A.; Jagosh, J.; Greenhalgh, T. Quality and reporting standards, resources, training materials and information for realist evaluation: The RAMESES II project. Heal. Serv. Deliv. Res. 2017, 5, 1–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and beyond: From Research Design to Analysis and Publication; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.S.; Beck, C.T. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice; Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor Fact Sheet # 73: Break Time for Nursing Mothers under the FLSA. 2013. Available online: http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs73.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Protection of Human Subjects; Notice of Report for Public Comment. 1979; p. 44. Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/osa/phre/web/pdf/belmont_report_frv44n76.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Secretaría de Economía. Norma Mexicana NMX-R-025-SCFI-2015 en Igualdad Laboral y No Discriminación. 2015. Available online: https://www.conapred.org.mx/userfiles/files/NMX-R-025-SCFI-2015_2015_DGN.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Secretaría de Gobernación. DECRETO por el que se adicionan y reforman diversas disposiciones de la Ley General de Salud; de la Ley Federal de los Trabajadores al Servicio del Estado, Reglamentaria del Apartado B) del artículo 123 Constitucional; de la Ley del Seguro Social; de la Ley del Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado; de la Ley para la Protección de los Derechos de Niñas, Niños y Adolescentes, y de la Ley General de Acceso de las Mujeres a una Vida Libre de Violencia (DECREE adding and amending various provisions of the General Health Law; the Federal Law of Workers in the Service of the State, Regulatory of Section B of Article 123 of the Constitution; the Social Security Law; the Law of the Institute of Security and Social Services of State Workers; the Law for the Protection of the Rights of Children and Adolescents, and the General Law on Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence). 2014. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5339161&fecha=02/04/2014 (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- INEGI Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo. Nueva Edición (ENOEN)-Cifras Durante el Primer Trimestre de 2021 (INEGI Results of the National Occupation and Employment Survey. New Edition (ENOEN)-Figures during the First Quarter of 2021). 2021. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2020/iooe/iooe2020_01.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Victora, C.G.; Habicht, J.P.; Bryce, J. Evidence-Based Public Health: Moving Beyond Randomized Trials. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, R.; Greenhalgh, T.; Harvey, G.; Walshe, K. Realist review—A new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Heal. Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.S.; Harger, L.; Beake, S.; Bick, D. Women’s and Employers’ Experiences and Views of Combining Breastfeeding with a Return to Paid Employment: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2021, 66, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, V.C.; Gigler, M.E.; Widenhouse, J.M.; Jillani, Z.M.; Taylor, Y.J. A Socioecological Approach to Understanding Workplace Lactation Support in the Health Care Setting. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaría del Trabajo y Prevención Social. Promueven Sectores Obrero y Empresarial Lactarios en Centros de Trabajo (Labor and Business Sectors Promote Lactation Rooms in Workplaces). Boletín No. 652. 2016. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/stps/prensa/promueven-sectores-obrero-y-empresarial-lactarios-en-centros-de-trabajo (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Research Center for Equitable Development. Índice País Amigo de la Lactancia Materna: Caso México 2020 (Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Country Index: Mexico 2020 Case Study). 2016. Available online: https://equide.org/proyecto_bbf_2020_pb.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Flacking, R.; Dykes, F.; Ewald, U. The influence of fathers’ socioeconomic status and paternity leave on breastfeeding duration: A population-based cohort study. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandahl, M.; Stern, J.; Funkquist, E.L. Longer shared parental leave is associated with longer duration of breastfeeding: A cross-sectional study among Swedish mothers and their partners. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaría de Gobernación. ACUERDO Mediante el cual se Aprueba la Modificación del Permiso de Paternidad, Previsto tanto en los Lineamientos en Materia de Recursos Humanos, Servicio Profesional y Personal de Libre Designación del INAI como en el Manual de Percepciones de los Servidores Públicos del Instituto Nacional de Transparencia, Acceso a la Información y Protección de Datos Personales (DECREE Approving the Modification of the Paternity Leave Provided for in the Guidelines on Human Resources, Professional Service and Free Appointment Personnel of INAI as well as in the Manual of Perceptions of Public Servants of the National Institute of Transparency, Access to Information and Protection of Personal Data). 2021. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5631203&fecha=29/09/2021 (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Cools, S.; Fiva, J.H.; Kirkebøen, L.J. Causal effects of paternity leave on children and parents Sara Cools BI Norwegian Business School BI Norwegian Business School. Scand. J. Econ. 2015, 117, 801–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar-compte, M.; Teruel, G.M.; Flores-peregrina, D.; Carroll, G.J.; Buccini, S. Costs of maternity leave to support breastfeeding; Brazil, Ghana and Mexico. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Line of Business | Sector | Total Number of Employees 1 | Number of Female Employees 1 | Lactation Room Implemented |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mérida, Yucatán | ||||

| Shopping mall | Private | 800 | 500 | Yes |

| Public services | Public | 65 | 40 | No |

| Media and communication | Private | 900 | 400 | No |

| Health services | Private | 425 | 260 | No |

| Chihuahua, Chihuahua | ||||

| Media and communication | Private | 230 | 150 | No |

| Software development | Private | 108 | 51 | No |

| Educational services | Public | 91 | 48 | No |

| Purchase/sale of air conditioning and refrigeration | Private | 137 | 37 | No |

| Technology Development | Private | 131 | 57 | No |

| Manufacturing of industrial containers | Private | 223 | 24 | No |

| Guadalajara, Jalisco | ||||

| Educational services | Private | NA | NA | Yes |

| Tourism services | Private | 146 | 51 | Yes |

| Environment | Public | 521 | 265 | Yes |

| Monterrey, Nuevo León | ||||

| Beverage and tobacco industry | Private | 471 | 38 | Yes |

| Characteristic | Total |

|---|---|

| Type of interviewee (%) | |

| Beneficiaries or potential beneficiaries 1 | 49 (44.2) |

| Male employees | 41 (36.9) |

| Managers and human resources personnel 2 | 21 (18.9) |

| Sex (%) | |

| Female | 63 (56.8) |

| Male | 48 (43.2) |

| Marital Status (%) | |

| Married/free union | 93 (83.8) |

| Single | 15 (13.5) |

| Divorced | 3 (2.7) |

| Interviewees’ age (Years) (SD) | 36.6 (±9.5) |

| Education level (%) | |

| Lower secondary 3 or Upper secondary incomplete 4 | 9 (8.1) |

| Upper secondary complete 4 | 11 (9.9) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 67 (60.4) |

| Other 5 | 24 (21.6) |

| Category | Subcategory | Original Quotations | English Translated Quotations 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context | Flexibility work schedule/workload | “… Haz de cuenta, tienes ocho horas de trabajo y durante seis meses te dan media hora, ya sea que tú la tomes antes y después o que lo tomes durante el día. Entonces, yo lo que hacía era que… no sé si tú sepas, pero es doloroso tener la leche, entonces yo prefería tomar mis medias horas en los lactarios que salir o llegar más tarde porque era muy incómodo y doloroso para mí estar aguantando hasta salir. Entonces, tú elegías salir antes o tomar tus medias horas para tus extracciones…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Guadalajara, [B01]) | “… You have eight hours of work and for six months they give you half an hour, whether you take it before and after or you take it during the day. So, what I did was… I don’t know if you know, but it is painful to have the milk, so I preferred to take my half hour in the lactation rooms than to leave or arrive later because it was very uncomfortable and painful for me to be waiting until I left. So, you could choose to leave earlier or take half an hour for your extraction…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Guadalajara, [B01]) |

| Lactation services | “… Pues, prácticamente se tiene la sala, se tienen las pláticas, lo coordinamos entrega de trípticos, lo hacemos sobre todo en el mes de agosto, que es la Semana de la Lactancia, son prácticamente como recordarle a la gente que existe (la sala). Obviamente también la damos a conocer en cada curso de inducción que se le da al personal nuevo. Entonces, son esas prácticas que se hacen, y se les da tanto a mujeres como a hombres, en nuestro curso de inducción y en el mes de la lactancia…” (Manager and HR personnel, Guadalajara [RRHH]) | “… Well, we practically have the room, we have the talks, we coordinate the delivery of triptychs, we do it especially in the month of August, which is Breastfeeding Week, they are practically like a reminder to people that it exists (the lactation room). Obviously, we also make it known in each induction course given to new personnel. So, it’s those practices that are done, and it is given to both women and men, in our induction course and in the breastfeeding month…” (Manager and HR personnel, Guadalajara [RRHH]) | |

| Previous experience with BF | [No support] “… Ahí sí porque no sabía, fíjate, porque yo le comenté a mi pediatra… bueno, ya cuando pasaron los años yo me di cuenta porque pensé que me había quedado sin leche, pero no, en realidad fue porque yo no me lo ponía constantemente y no producía, entonces yo desconocía eso, yo no sabía que tenía que estármelo poniendo a cada rato para que mi pecho produciera más leche, y ahora que lo supe dije “no, pues no es cierto, yo nunca me quedé sin leche, no hice que produjera leche…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Chihuahua, [B04]) | [No support] “… I didn’t know, you see, because I told my pediatrician…well, when the years went by I realized it because I thought I had run out of milk, but no, in reality it was because I was not extracting constantly and I did not produce milk, so I did not know that, I did not know that I had to extract all the time so that my breast would produce more milk, and now that I knew I said “no, well it is not true, I never ran out of milk, I did not make it produce milk…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Chihuahua, [B04]) | |

| Distance between workplace and infant | [Barrier] “…Pues vivo en una distancia lejana de aquí, entonces no había ni forma de ir a mi casa. Que viviera cerca sería lo ideal, agarro mi media hora, le doy leche, vengo y regreso, pero desgraciadamente así las cosas laborales…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Mérida, [B02]) | [Barrier] “…Well, I live a long way from here, so there was no way to go home. If I lived close it would be ideal, I would take my half hour, give her breast milk, come, and go back, but unfortunately that’s the way things are at work…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Mérida, [B02]) | |

| Mechanism | Awareness of the intervention | [Promotion by workplaces] “… Pues mira, cuando abrimos la sala de lactancia, se abrieron más o menos al mismo tiempo en todas las plantas, yo estaba en Orizaba, me tocó que nos platicaron un poco, y cuando llegas a la planta te platican de las prestaciones, de las instalaciones. No es que tengas un entrenamiento mensual porque no se necesita, pero lo que sí he visto, es que cuando alguien se embaraza pues sí se le habla un poquito más a detalle…” (Male employee, Monterrey, [H01]) | [Promotion by workplaces] “… Well, look, when we opened the lactation room, they opened more or less at the same time in all the stores, I was in Orizaba, they told us a little about it, and when you arrive at the store they tell you about the benefits and the facilities. It is not that you have monthly training because it is not necessary, but what I have seen is that when someone gets pregnant, they talk to them a little more in detail…” (Male employee, Monterrey, [H01]) |

| Usage of the intervention | “… Y ahorita mis extracciones las hago ahí… es la sala principal, tiene como una cocinita y en la cocinita tienen un cuartito donde guardan así como los insumos y ahí me encierro. Pido mi llave a la recepcionista, le digo “préstame la llave” y voy y me encierro y ya nadie puede entrar hasta que salgo…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Chihuahua, [B03]) | “… And now I do my milk extractions there… it is the main room; it has a small kitchen and, in the kitchen, they have a little room where they keep the supplies and I lock up there. I ask the receptionist for my key, I say: “lend me the key” and I go and lock up and nobody can get in until I get out…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Chihuahua, [B03]) | |

| Mechanism and Sub-Outcome | Workplace BF culture | [Benefits beyond the law] “… Se tiene un grupo que lleva la jefa de Relaciones Laborales, que se llama “Women at XXX”, entonces hay reuniones de temas de liderazgo, pláticas… uno de los temas en algún momento fue el del lactario, el embarazo, igualdad de oportunidades, varios temas que tocaban, pláticas directas con el director, estaba muy padre. Entonces, nosotros tenemos muy claro el tema de fomentar la lactancia materna…” (Manager and HR personnel, Monterrey, [RRHH01]) | [Benefits beyond the law] “… We have a group led by the head of Labor Relations, called “Women at XXX”, so there are meetings on leadership issues, talks… one of the topics at some point was the breastfeeding program, pregnancy, equal opportunities, several topics that were discussed, direct talks with the director, it was very cool. So, we are very clear on the issue of promoting breastfeeding…” (Manager and HR personnel, Monterrey, [RRHH01]) |

| Physical environment | [No physical space] “… Sí, porque todo es de vidrio, entonces era muy complicado porque era un local muy grande donde yo nada más estaba con dos hombres, éramos dos hombres y yo, entonces sí les decía: “muchachos, me voy a encerrar en el clóset, no pasen a la cocina, me voy a estar sacando leche, por si alguien pregunta por mí”, no hubo ningún problema. El clóset estaba muy chiquito […] tenía yo ahí mi silla, mi conector, me sacaba la leche, la guardaba en el refrigerador…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Chihuahua, [B02]) | [No physical space] “… Yes, because everything is made of glass, so it was very complicated because where I was, it was a very big place, there were two men and I, so I told them: “guys, I’m going to lock myself in the closet, don’t go to the kitchen, I’m going to extract milk, in case someone asks for me”, there was no problem. The closet was very small […] I had my chair there, my connector, I extracted my milk, I kept it in the fridge…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Chihuahua, [B02]) | |

| Supervisor support | [Inadequate support] “…creo que existe todavía un poco de machismo de los líderes, a lo mejor. Creo que es parte de no reconocer esto que es importante para el bienestar de sus empleados. Creo que va por ahí…” (Male employee, Guadalajara, [H02]) | [Inadequate support] “…I think there is still a little bit of male chauvinism from the leaders, maybe. I think it’s part of not recognizing that this is important for the well-being of their employees. I think it goes that way…” (Male employee, Guadalajara, [H02]) | |

| Co-worker support | [Perceived support] “… Igual la verdad fueron muy respetuosas, ayuda que sean puras mujeres creo que si hubiera algún hombre hubiera sido diferente […] había una mujer que también daba pecho y pues como que nos apoyamos un poco…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Mérida, [B03]) | [Perceived support] “… The truth is that they were very respectful, it helps that they are all women, I think that if there had been a man it would have been different […] there was a woman who was also breastfeeding and we kind of supported each other a little bit…” (Beneficiary or potential beneficiary, Mérida, [B03]) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernández-Cordero, S.; Vilar-Compte, M.; Litwan, K.; Lara-Mejía, V.; Rovelo-Velázquez, N.; Ancira-Moreno, M.; Sachse-Aguilera, M.; Cobo-Armijo, F. Implementation of Breastfeeding Policies at Workplace in Mexico: Analysis of Context Using a Realist Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042315

Hernández-Cordero S, Vilar-Compte M, Litwan K, Lara-Mejía V, Rovelo-Velázquez N, Ancira-Moreno M, Sachse-Aguilera M, Cobo-Armijo F. Implementation of Breastfeeding Policies at Workplace in Mexico: Analysis of Context Using a Realist Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042315

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Cordero, Sonia, Mireya Vilar-Compte, Kathrin Litwan, Vania Lara-Mejía, Natalia Rovelo-Velázquez, Mónica Ancira-Moreno, Matthias Sachse-Aguilera, and Fernanda Cobo-Armijo. 2022. "Implementation of Breastfeeding Policies at Workplace in Mexico: Analysis of Context Using a Realist Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042315

APA StyleHernández-Cordero, S., Vilar-Compte, M., Litwan, K., Lara-Mejía, V., Rovelo-Velázquez, N., Ancira-Moreno, M., Sachse-Aguilera, M., & Cobo-Armijo, F. (2022). Implementation of Breastfeeding Policies at Workplace in Mexico: Analysis of Context Using a Realist Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042315