Respect in the Eyes of Non-Urban Elders: Using Qualitative Interviews to Distinguish Community Elders’ Perspective of Respect in General and Healthcare Services

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background and Study Participants

2.2. Data Collection

- Gender:☐ (1) Male ☐ (0) Female

- Birth: year

- Education Level:☐(01) Elementary School ☐(02) Junior HighSchool☐(03) Senior High School

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

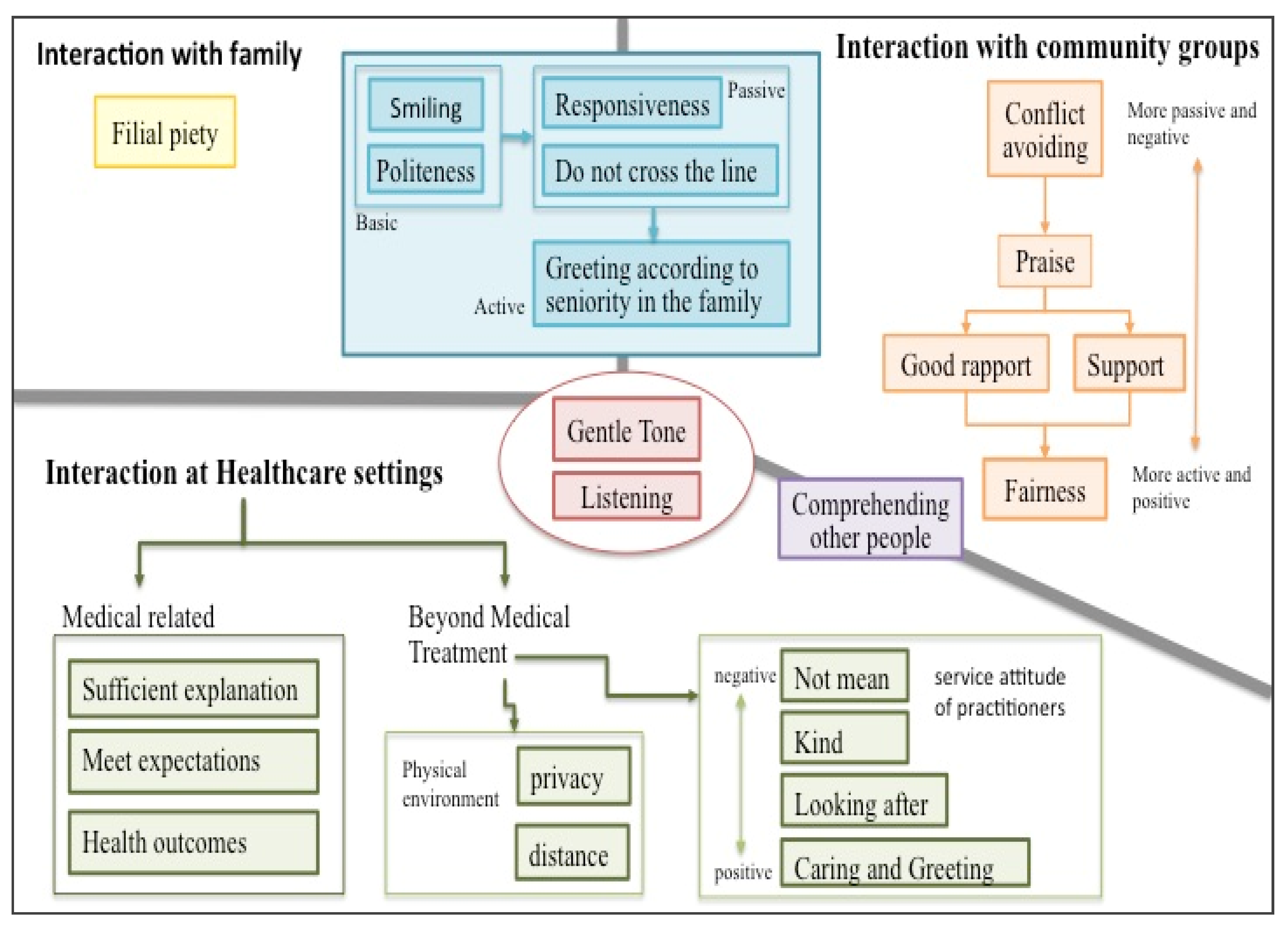

3.1. Respect in General

- Respect is a way of verbal expression, for example, “gentle tone”, and “smile when speaking”.Participant:…soft voice and lower volume when speaking (L07M71)

- Respect is a non-verbal behavior including “listening”, “fairness”, “comprehending other people”, “do not cross the line”, “good rapport”, support”, “politeness”, and “filial piety”.Participant: Respect is…understanding each other, each other, right? Right, understand each other, it would be fine as long as we perceive what he thinks (U01F72).Participant: Respect! It means do not interfere with other people. Other people do not interfere with us either (U27F70).Participant: Respect for the view is mutual, you care about me and I will care about you so, should be mutual (U15M77).Participant: Respect is…nothing particular, just be polite, with courtesy …(U24M71).Participant:…they do respect me; two kids, one works at a railway station and the other takes care the store, (Interviewer: So, your kids all take care of you is a way of showing respect to you?) Participant: Yes, yes! (U06F80).

- Respect is a behavior combined with appropriate language including “responsiveness”, “conflict avoiding”, “praise”, and “greeting according to seniority in the family”.Participant: Respect is…(a short pause)…There were responses after you spoke (L12F75).Participant: Respect means do not argue, do not quarrel (U08M75), do not offend other people, everyone should have mutual affection (L19F67).Participant: Everyone respects me. …(Interviewer: So, how does everyone respect you?)…I told them that you are much older than I am, you cannot call me as “elder sister”…(L26F750).

3.2. Respect in Healthcare Settings

3.2.1. Respect Is a Way of Verbal Expression

Participant: people will respect us more, the practitioners are all very courteous,…he treated us not in a mean way…(L01F70).

Participant: …It was OK! (Interviewer: Can you tell me why it was OK?) Participant: The tone of healthcare providers was acceptable! (L07M71).

Participant: respect me?…I felt he was kind when he spoke (L07M71),…Ya, both doctors and nurses spoke in a very nice way (L11F75).

3.2.2. Respect Is a Non-Verbal Behavior

Participant: I felt that everybody is very kind, with very good service, that’s it, this is the way to show respect to me (L25F68).

Participant: The doctor is more polite, more respectful of what you say, will listen to what you say, and will listen to whatever you want to say (U14M84).

Participant: They are very good, so they are very respectful. I had my tooth extracted, they were afraid that I would fall and would like to escort me to the station …the doctor asked a nurse to take me to a bus station (U22F73).

Participant: There is respect… that was a nurse, he was doing an ultrasound, when there was an issue, he said “let’s do it again, let’s do it again”, he would re-scan the spot thoroughly or ask you to come back another time (U24M71).

Participant: being respected… he would check what discomfort I described, prescribing medication for me (L17M84).

Participant: …cure me, that’s it…that’s respect…we wouldn’t visit again if he didn’t cure us, that’s impossible (U19M82)?

3.2.3. Respect Is a Behavior Combined with Appropriate Language

Participant: respect…they would say ”sir, sit here and wait for a while”, that’s it, this is what I need. This is respect, what would it be otherwise? (L01F70). Participant: respect me…doctors are very nice nowadays when I entered, he invited me to sit near him, they all very kind (L03F74).

Participant: respect in this environment, they were nice to us, asked you “Did you eat This morning?...You need to pay attention when going out.” It made me feel this doctor is very nice (L15F73).

Participant: respect…doctors were very nice, currently, he knew how to treat me, “Hey, don’t eat sweet stuff!” He made fun of me, “You will get a needle if you eat sweet stuff again!” (Smiling), harassing me (L20F81).

Participant: Respect…what to say…the doctor pointed out the issue and how to treat it (U23M65).

3.2.4. Respect Is a Perception of Physical Environment Arrangement in Healthcare Settings

Participant: Being respected… doctor sat closer to you, discussed the inner issue with you, a doctor sat across the table and the nurse was beside him/her, it felt like being examined (L04M76).

Participant: Respect for patients who come to see the doctor….you should offer privacy when they need it, not just open to everybody (U13F71).

3.2.5. The Elderly’s Perceptions of Respect in the Healthcare Setting Will Vary According to Sociodemographic Characteristics

- Area difference: The elderly in Lukang care more about the verbal expression of healthcare providers. For example, Participant: respect me?…I felt he was kind when he spoke (L07M71),…Ya, both doctors and nurses spoke in a very nice way (L11F75). On the contrary, the elderly in Ershui are more concerned with “listening to the elderly”. For example, The doctor is more polite, more respectful of what you say, and will listen to what you say, and will listen to whatever you want to say (U14M84).

- Gender difference: Females stressed “offering care services other than healthcare services” and “being looked after”. For example, Participant: there is respect… that was a nurse, he was doing an ultrasound, when there was an issue, he said “let’s do it again, let’s do it again”, he would re-scan the spot thoroughly or ask you to come back another time (U24M71). Respect…they would say ”sir, sit here and wait for a while”, that’s it, this is what I need. This is respect, what would it be otherwise? (L01F70). Males, however, payed more attention to “obtaining final health results” such as “Participant: …cure me, that’s it…that’s respect…we wouldn’t visit again if he didn’t cure us, that’s impossible (U19M82)?”.

3.3. The Comparison between “Respect in Daily Life” and “Respect in Healthcare Settings”

4. Discussion

4.1. Respect in the Eyes of the Elderly

- 3.

- Compared to general situations, it is easier to present a clearer and different perspective on a specific situation. A healthcare setting is not only a more specific context for the seniors but also a place to treat their health problems. Interpersonal interactions in this setting include both general and therapeutic levels. In addition to interpersonal interaction, it also includes the perception of environmental arrangements. From the elderly’s statement, the expectation of respect for the healthcare setting is implied: I am not just a health problem to be treated, but a person.

- 4.

- The elderly believe subconsciously that respect in healthcare settings contain his/her expectation in utilizing healthcare services including space planning. The closer spatial distance seems to make the elderly feel more respected. This result is consistent with the psychological view that spatial distance reflects psychological distance, and that psychological distance can be reduced by shortening spatial distance [26].

4.2. The Subjectivity of Respect: Respecting Others or Being Respected

4.2.1. In Daily Life, Respecting Others and Being Respected Are Two Sides of the Same Coin

4.2.2. Seniors Are More Concerned about “Being Respected” in the Healthcare Setting

4.3. The Discussion of the View for the Elderly toward Respect in Healthcare Settings

4.3.1. The Area Differences in the View toward Respect in the Healthcare Setting

4.3.2. The Gender Differences in the View toward Respect in the Healthcare Setting

4.3.3. The Characteristics of Respect in Healthcare Settings

4.4. Study Limitation

4.4.1. A General and a Short Outline of the Interview

4.4.2. Participants Were Limited by Senior Attendees in Community Care Stations

4.5. Implications

4.5.1. Understanding Seniors’ Perceptions of Respect Is Useful for Implementing Age-Friendly Cities

4.5.2. It Is Recommended That Healthcare Providers should View the Patient as a Whole Person, Not as a Health Problem to Be Remediated

4.5.3. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beach, M.C.; Branyon, E.; Saha, S. Diverse patient perspectives on respect in healthcare: A qualitative study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 2076–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Words, Respect. ChineseWords.org, R.O.C (Taiwan). (In Chinese). 2021. Available online: https://www.chinesewords.org/dict/95538-35.html (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Darwall, S.L. Two Kinds of Respect. Ethics 1977, 88, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll-Dayton, B.; Saengtienchai, C. Respect for the elderly in Asia: Stability and change. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1999, 48, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ronzi, S.; Pope, D.; Orton, L.; Bruce, N. Using photovoice methods to explore older people’s perceptions of respect and social inclusion in cities: Opportunities, challenges and solutions. SSM Popul. Health 2016, 2, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ronzi, S.; Orton, L.; Buckner, S.; Bruce, N.; Pope, D. How is Respect and Social Inclusion Conceptualised by Older Adults in an Aspiring Age-Friendly City? A Photovoice Study in the North-West of England. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. Population and Housing Census; Executive Yuan, Taipei City, R.O.C: Taipei, Taiwan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Development Council. Trend in the Percentage of Elderly Population (In Chinese); Executive Yuan, Taipei City, R.O.C: Taipei, Taiwan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’cities. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.C.; Kuo, H.W.; Lin, C.C. Current Status and Policy Planning for Promoting Age-Friendly Cities in Taitung County: Dialogue Between Older Adults and Service Providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, G.; Mrengqwa, L.; Geffen, L. They don’t care about us: Older people’s experiences of primary healthcare in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naidoo, K.; van Wyk, J. What the elderly experience and expect from primary care services in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam Med. 2019, 11, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agyemang-Duah, W.; Arthur-Holmes, F.; Peprah, C.; Adei, D.; Peprah, P. Dynamics of health information-seeking behaviour among older adults with very low incomes in Ghana: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskenniemi, J.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Suhonen, R. Respect in the care of older patients in acute hospitals. Nurs. Ethics 2013, 20, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Changhua County Government Department of Agriculture. Changhua Combines Industry, Government, and Academia for the First Time in Cross-Region Integration to Organize the Agricultural Innovation Institute Forum (In Chinese); Changhua County Government, Changhua County, R.O.C: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Labor Taichung-Chunghua-Nantou Regional Branch, Workforce Development Agency. R.O.C (Taiwan). (In Chinese). 2018. Available online: https://www.wda.gov.tw/en/cp.aspx?n=D2DEEE3B0F86AA88&s=575F716EF3A537C0 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Wikipedia, Changhua County. R.O.C (Taiwan). (In Chinese). 2021. Available online: https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-tw/%E5%BD%B0%E5%8C%96%E7%B8%A3 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Wikipedia, Lukang Township County. R.O.C (Taiwan). (In Chinese). 2021. Available online: https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%B9%BF%E6%B8%AF%E9%8E%AE (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Social and Family Affairs Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare, Community Care Site. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taipei City, R.O.C (Taiwan). 2021. Available online: https://ccare.sfaa.gov.tw/home/other/about (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Changhua County Government Department of Social Affairs, Senior Citizens Section Community Care Site. Changhua County Government, Changhua County, R.O.C (Taiwan). 2021. Available online: https://social.chcg.gov.tw/07other/other01_con.asp?topsn=711&data_id=11084 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Birks, M.; Mills, J. Grounded Theory: A practical Guide; SAGE Publishing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cairns, D.; Williams, V.; Victor, C.; Richards, S.; Le May, A.; Martin, W.; Oliver, D. The meaning and importance of dignified care-findings from a survey of health and social care professionals. BMC Geriatr. 2013, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, L.E.; Bargh, J.A. Keeping one’s distance: The influence of spatial distance cues on affect and evaluation. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janevic, T.; Sripad, P.; Bradley, E.; Dimitrievska, V. There’s no kind of respect here A qualitative study of racism and access to maternal health care among Romani women in the Balkans. Int. J. Equity Health 2011, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kujawski, S.; Mbaruku, G.; Freedman, L.P.; Ramsey, K.; Moyo, W.; Kruk, M.E. Association between disrespect and abuse during childbirth and women’s confidence in health facilities in Tanzania. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 2243–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickle, N.; Gamble, J.; Creedy, D.K. Women’s reports of satisfaction and respect with continuity of care experiences by students: Findings from a routine, online survey. Women Birth 2020, 34, e592–e598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K. An Introduction to the Sociology of Health and Illness; SAGE Publishing: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, J.; Rastogi, S.; Jadon, A. Changing doctor patient relationship in India: A big concern. Int. J. Commun. Med. Public Health 2019, 6, 3160–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei-Hui, T.; Feng-Hwa, L. The Use of Appropriate Follow-up Responses to Patients as a Linguistic Way of Facilitating Doctor-patient Communication. J. Med.Educ. 2001, 5, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Shu-Chen, K.; Hsiao-Chu, W. Effect of Doctor-Patient Interactions on Medication Use for Insomnia Patients. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 3, 177–201. [Google Scholar]

- Eliacin, J. Factors influencing patients’ preferences and perceived involvement in shared decision-making in mental health care. J. Ment. Health 2015, 24, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tseng, Y.-H.; Li, Y.-L.; Luu, S.; Luh, D.-L. Respect in the Eyes of Non-Urban Elders: Using Qualitative Interviews to Distinguish Community Elders’ Perspective of Respect in General and Healthcare Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042171

Tseng Y-H, Li Y-L, Luu S, Luh D-L. Respect in the Eyes of Non-Urban Elders: Using Qualitative Interviews to Distinguish Community Elders’ Perspective of Respect in General and Healthcare Services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042171

Chicago/Turabian StyleTseng, Yu-Hsien, Yu-Ling Li, Shyuemeng Luu, and Dih-Ling Luh. 2022. "Respect in the Eyes of Non-Urban Elders: Using Qualitative Interviews to Distinguish Community Elders’ Perspective of Respect in General and Healthcare Services" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042171

APA StyleTseng, Y.-H., Li, Y.-L., Luu, S., & Luh, D.-L. (2022). Respect in the Eyes of Non-Urban Elders: Using Qualitative Interviews to Distinguish Community Elders’ Perspective of Respect in General and Healthcare Services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042171