Reflections on Experiencing Parental Bereavement as a Young Person: A Retrospective Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Method

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Materials and Procedure

2.4. Analysis

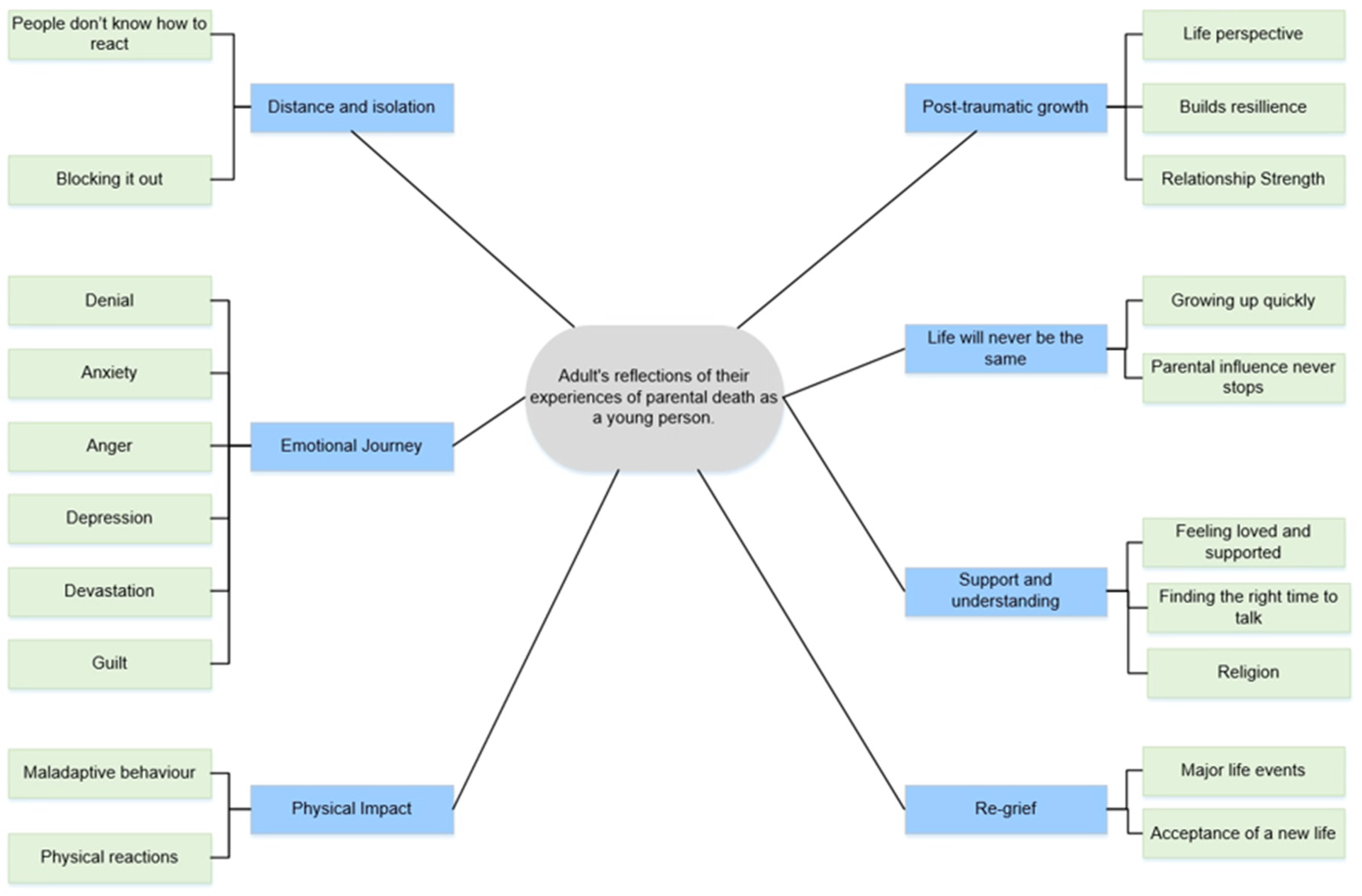

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Distance and Isolation

3.1.1. People Don’t Know How to React

“I think they just didn’t know what to say, so they didn’t…”(Gail, 24 years old when her dad died)

“I was quite young, so I think a lot of my friends didn’t know how to act…I think you just kind of like pussyfoot around it…”(Laura, 11 years old when mum died)

“I think it is that they don’t know what to say and it is just really difficult, and it almost becomes like they are stepping on eggshells around me.”(Kate, 18 years old when her mum died)

“So, people who have never lost a parent, they feel so sorry when I mention it and they get really panicky and they are like “OMG, what do I do, what do I do.”(Louise, 13 years old when her dad died)

“They have this look, where they feel sorry for you, and that pisses me off. Because they don’t get it.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“They [people who have not been bereaved] say “I’m sure in a couple of days you’ll feel better”. No, actually, I won’t feel better, no, that’s crap don’t talk to me… People who are in that situation understand. It is like an unknowing acknowledgment that the person will always be part of your life… people who have never been in that situation, they are very naïve to it.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

3.1.2. Distancing from Others

“I isolated myself and didn’t want to hang out with people as much as I used to… I was just really quiet, although I had friends, I would prefer to be by myself.”(Louise, 13 years old when her dad died)

“I didn’t wanna go back [to work], I didn’t want to face anyone.”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

“So, it is easier to just not speak to people. Because genuinely you are not feeling alright. You hate your life and miss the people you have lost. You wanna start again and technically the only way to start again with those people is not to be in the world and you do genuinely have those thoughts like over and over again…”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“I just shut down. I couldn’t go anywhere. I couldn’t leave the house. I was just paralysed, I couldn’t do anything.”(Ben, 18 years old when his dad died)

3.1.3. Blocking It Out

“I’m the kind of person who will keep myself busy to avoid feeling about it sometimes and I think that was kind of how I coped with it. So, my mental health wasn’t as great as it could have been at the time.”(Kate, 18 years old when her mum died)

“I did a lot of travelling. My sisters would say that was because I was struggling and I needed to be away.”(Zara, 23 years old when her mum died)

“I wasn’t letting any of my emotions through. So, they were just building up, building up and building up and all of a sudden I can’t get out of bed… To be honest, really I have crammed any single minute in my life to work. So, I don’t have to think about all my emotions. So, I just work constantly.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“How I didn’t cry and how I didn’t lose myself, I just don’t know. I just felt like he wouldn’t want me to feel bad that he is gone…”(Jack, 14 years old when his dad died)

3.2. Theme 2: Emotional Journey

3.2.1. Denial

“My mum was in the chapel of rest and I was trying to wake her up and I am just screaming this can’t be real.”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

“It was like everything was in slow motion, just it is almost surreal. It is just, yeah, you are almost looking at yourself outside you know, it’s like, I don’t know, you are almost part of a film.”(Ben, 18 years old when his dad died)

3.2.2. Anger

“I was an angry 20-year-old. Angry. Angry. Angry… I think I had a lot of anger that I didn’t have anywhere to put. I had nowhere to vent it out, so I was taking it out on myself. Self-harming reduced that anger a hell of a lot.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“I was really sort of frustrated. Really angry I went through a really sort of angry, angry phase.”(Jim, 17 years old when his mum died)

3.2.3. Anxiety

“I am completely paranoid that I am going to die.”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

“I was never anxious or I was like a very upbeat person, but somehow after that I became more anxious.”(Louise, 13 years old when her dad died)

“I suffered with anxiety, quite badly.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

3.2.4. Depression

“I wouldn’t say I was depressed, but obviously there are days where I have felt a bit lonely and I have thought this would be so different if my mum was here.”(Laura, 11 years old when her mum died)

“Grieving can be quite a deteriorating process it can be quite a decaying, depressive period and once that depression gets hold of you. I think the worse…”(Greg, undisclosed age when his dad died)

“I was diagnosed with depression [following parental death]…”(Ben, 18 years old when his dad died)

“It did sink me into a depression, I was on anti–depressants”(Gail, 24 years old when her dad died)

3.2.5. Guilt

“I felt really guilty because I had only just moved out the November before.”(Gail, 24 years old when her dad died)

“The guilt at things you said, things you didn’t say, you attempt to make amends for”(Greg, undisclosed age when his dad died)

“I always remember feeling really guilty about it in the really early stages about enjoying myself. Having fun, I felt really guilty about it.”(Jim, 17 years old when his mum died)

“Then I feel guilty for her [a friend] cos she is probably thinking “Shit, the poor woman’s going to commit suicide. I better tell her she is loved.””(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

3.2.6. Devastation

“How did it affect me; it literally broke me. Broke my whole entire world.”(Marie, 20 years since her dad died)

“From that day, everything just got flipped on its head.”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

“I feel like that [the death of a parent] is probably the worst thing that could ever happen to anyone…”(Laura, 11 years old when her mum died)

3.3. Theme 3: Physical Impact

3.3.1. Maladaptive Behaviour

“I just couldn’t be bothered, I wasn’t, I just did not get hungry for ages and I struggle with food now if I get stressed. I just don’t eat, just don’t get hungry.”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

“I don’t think I ate for a long time. So, I lost a lot of weight. I was only little anyways.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“It would be right in front of the telly, eat whatever the hell I want. Whatever, whenever as much as I wanted. I didn’t care, so yeah I probably put on a stone, maybe two.”(Gail, 24 years old when her dad died)

“Marijuana worked really well for the first 10 years maybe in keeping my emotions, and then it started not to work…You couldn’t make it to the bed or shower, or you couldn’t feed yourself.”(Greg, undisclosed age when his dad died)

“Mostly be exhausted and you would be drained because you were always, if you were not crying you were always talking to people…”(Rebekah, 16 years old when her mum died)

3.3.2. Physical Reactions

“Loads of panic attacks in places like if I was stuck in a lift, if I was in a lift and the lift was taking too long or if I was in a lecture theatre sandwiched between people. I would start to panic and stuff like that…”(Zara, 23 years old when her mum died)

“Then I got diagnosed with Fibromyositis Obviously, there is not much research into it but they said one factor… most people get diagnosed with it when there has been a big trauma or loss in their life”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

3.4. Theme 4: Post-Traumatic Growth

3.4.1. Life Perspective

“Life is for living and it is for living now because you never know what is going to happen.”(Zara, 23 years old when her mum died)

“I try and sort of like take opportunities more. I do new things all the time. I try and sort of make the most of everything.”(Jim, 17 years old when his mum died)

“You don’t know what is around the corner. Like everything can change in the blink of an eye.”(Rebekah, 16 years old when her mum died)

“I would be a much more selfish person now if I hadn’t gone through all that. I was a spoiled little brat as a kid. I was a Daddy’s girl and would snap my fingers and get what I wanted. Now I realise you can have stuff taken away from you really easily, so I appreciate it more.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

3.4.2. Builds Resilience

“I can stop any sort of nonsense in my life. Any maybe pitfalls that other people might have fallen into. You sort of harden up… I felt like I had to be sort of strong and just cope on my own. Sort of and become more self-sufficient almost.”(Ben, 18 years old when his dad died)

“Think I am so much stronger than what I would have been…”(Laura, 11 years old when her mum died)

“I have a high level of resilience cos I have had to. I have had no choice. I have had to overcome things.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“I had to start learning to speak up for myself, cos I was very shy, so it was like well no one else is going to talk up for me. I better do it for myself.”(Gail, 24 years old when her dad died)

3.4.3. Relationship Strength

“I say certainly the bereavement and the loss of my Dad definitely made us a lot closer.”(Ben, 18 years old when his dad died)

“We have got much closer because of it. Obviously after Dad we got closer but then after mum went, we got much closer cos we went, ‘it is just the two of us now’.”(Gail, 24 years old when her dad died)

“I think one thing it did surprisingly, it brought my family together.”(Louise, 13 years old when her dad died)

“Our family is disintegrated since my mum died.”(Zara, 23 years old when her mum died)

“She left a massive hole in both families when she passed away.”(Adam, 13 years old when his mum died)

“My family’s kind of quite diffused at this point.”(Chris, 21 years old when his dad died)

“I think my Dad was obviously going through his own stuff and I was going through my stuff and we didn’t gel at the time.”(Kate, 18 years old when her mum died)

3.5. Theme 5: Life Will Never Be the Same

3.5.1. Growing Up Quickly

“I did feel I had to grow up quickly.”(Kate, 18 years old when her mum died)

“I was looking after my little brother. Doing the things that my mum would have done for him… making sure the school trip has been paid for and stuff like that and I guess it left a bit of weight on my shoulders.”(Adam, 13 years old when his mum died)

“You know just your mum and sisters need you, the house needs maintenance and the bills need to be paid and things like that need doing.”(Greg, undisclosed age when his dad died)

“Well I was 22, and I wasn’t ready to grow up… and then I suddenly felt like I couldn’t leave my Dad.”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

“The main thing, trying to look after my sister… you realise all the things, she would have probably asked my mum.”(Rebekah, 16 years old when her mum died)

“I felt like as now, as the head of the family, I had to pull myself together and get a job.”(Ben, 18 years old when his dad died)

“Family wise, like I felt I had, you know, a great deal of obligation, that perhaps I hadn’t felt before that point.”(Chris, 21 years old when his dad died)

3.5.2. Parental Influence Never Stops

“I think knowing he regretted certain things about his choices in life, made me think about mine a little more.”(Chris, 21 years old when his dad died)

“I think that would have changed me taking a year out. I don’t think she would have let that happen. I think I would have been straight into doing University.”(Laura, 11 years old when her mum died)

“She would have killed me if I decided to take a year out. She would have been like ‘no just go’.”(Kate, 18 years old when her mum died)

3.6. Theme 6: Support and Understanding

3.6.1. Feeling Loved and Supported

3.6.2. Family

“I lent on Jason a lot. Jason my husband now, my boyfriend at the time. You know he supported me, cuddled me and helped me at the funerals, that sort of thing.”(Gail, 24 years old when her dad died)

“I would go to him for support but it was actually the other way around I think in the initial stages. I think I dealt with it. Well not better, but I think my Dad just sort of, he was a bit more emotional to start off with, whereas I wasn’t.”(Jim, 17 years old when his mum died)

3.6.3. Peers

“We had a lot of friends who were very quick to sort of rally round my brother and I, to sort of be there for us.”(Adam, 13 years old when his mum died)

“Friends-wise I think we all just got a lot closer, because everyone was just constantly making the effort to make sure we were okay and stuff.”(Rebekah, 16 years old when her mum died)

“For the first couple of months, even the first year, everyone is so aware of what has happened… after a couple of months though you’re just left to like deal with it.”(Laura, 11 years old when her mum died)

“I think the first week to me, like everyone around me rally’s round, they bring you dinner, not that you wanna eat, and they bring you flowers and cards, and you get daily phone calls from like the whole world and then the minute you have the funeral and everyone goes back to normal and you are just left, everyone just gets on with their life and you’re like, yeah your life is carrying on but this is just the beginning for me”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

3.6.4. Professional

“They gave me like some leaflets and that was pretty much it as far as I remember. I think it was like sort of up to me if I wanted to get in touch they were always there. It was left open.”(Jim, 17 years old when his mum died)

“I don’t think I was offered any counselling.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“I will always credit them [Physical Education/PE teachers] a lot for helping me through the rough time in various ways.”(Adam, 13 years old when his mum died)

“She [PE teacher] just took more of an active role in making sure I was alright and sort of going above and beyond.”(Jim, 17 years old when his mum died)

“Eventually I went back to school, you had the support of the guidance teacher.”(Rebekah, 16 years old when her mum died)

“I didn’t really have any psychological support or help at all.”(Jack, 14 years old when his dad died)

“They might have offered something, I’m 80% sure they didn’t.”(Greg, undisclosed age when his dad died)

“They handed me a leaflet, but no one actually sat me down and said do you think this is something that you want to do. You know it was more handout a leaflet and that was it.”(Kate, 18 years old when her mum died)

“Then we walked out of there, I had a booklet that was it. A booklet. I’m like, you know I have lost everything today and I have got a book.”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

3.6.5. Finding The Right Time to Talk

“I would wobble and was crying at like 3 o’clock in the morning, you know, what I need is to go and see someone about this cos no one here really understands.”(Kate, 18 years old when her mum died)

“I don’t want talking therapy. I don’t want to talk about it all. I don’t feel comfortable talking about it. I think cos my family wasn’t like that, I just didn’t want counselling.”(Gail, 24 years old when her dad died)

“I don’t think I would have taken it even if I was offered it. You know it is not until my partner recently died and it was a year and half after his death and he died 2 years ago I started to get counselling.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“I did, it was about a year afterwards.”(Ben, 18 years old when his dad died)

“Just could not cope anymore, just could not cope.”(Greg, undisclosed age when his dad died)

“Think I didn’t really feel like I needed it…”(Adam, 13 years old when his mum died)

“So, seeing a therapist or kind of psychologist is the equivalent to being locked up in a mental institution, it’s just there is so much stigma about it. Even now in 2018”(Greg, undisclosed age when his dad died)

“It would mean like it’s [seeking professional support] always on your record and it’s a lot of stigma around that”(Louise, 13 years old when her dad died)

“I never went down that route because I just didn’t feel like I need to…”(Rebekah, 16 years old when her mum died)

3.6.6. Religion

“I didn’t care about anything. I was religious before my Dad died. Then hated God with a passion.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“But after this she [mum] started going to the mosque… but she wouldn’t do it religiously, she would do it in a spiritual way, and I think that helped her a lot.”(Louise, 13 years old when her dad died)

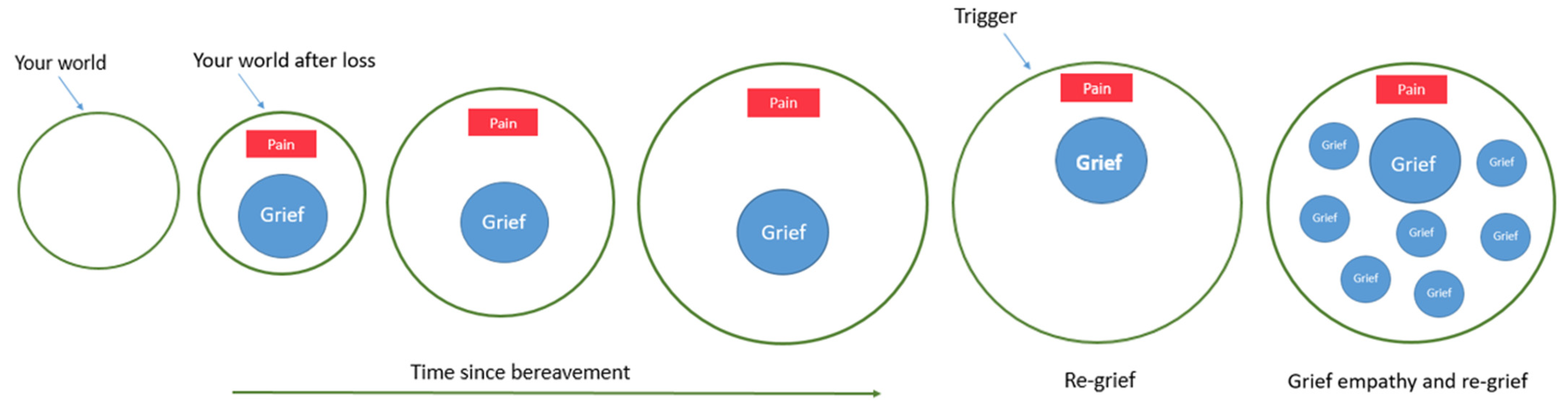

3.7. Theme 7: Re-Grief

3.7.1. Major Life Events

“It was weird, because I thought like daft things, like taking mum for a drive in a car and stuff when I passed, but obviously she wasn’t there to do that.”(Jim, 17 years old when his mum died)

“I have missed my Mum and Dad more since I have become a parent, because I haven’t been able to introduce them to their grandchildren.”(Gail, 24 years old when her dad died)

“Which then upsets me when I achieve something because I look around to tell someone and they are not there. Which I still find really hard.”(Marie, 20 years old when her dad died)

“There isn’t anybody like your Mum… You can ask other people the same questions but there is no one who is going to be able to reply like your Mum.”(Zara, 23 years old when her mum died)

3.7.2. Acceptance of a New Life

“I am bitter. I am, I do get quite bitter, on my wedding day I just sat there crying. Then I went up there [the grave] the day after my wedding and took my bouquet up and put it on my Mum.”(Claire, 22 years old when her mum died)

“All of a sudden, I just heard this song, very sad song, and I just started crying out of nowhere. Just bawling like a baby, you know and I had that feeling for like a day. I was like, bloody hell, where did that come from. I was like, is there anything else buried in there…”(Greg, undisclosed age when his dad died)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Records of Scotland Web. Monthly Data on Births and Deaths Registered in Scotland National Records of Scotland; National Records of Scotland Web, 2019. Available online: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/general-publications/weekly-and-monthly-data-on-births-and-deaths/monthly-data-on-births-and-deaths-registered-in-scotland (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Registrar General Annual Report 2018 Deaths Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency; Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2019. Available online: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/publications/registrar-general-annual-report-2018-deaths (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Office for National Statistics. Deaths registered in England and Wales-Office for National Statistics; Office for National Statistics, 2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregistrationsummarytables/2018 (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Child Bereavement Network. Key Estimated Statistics on Childhood Bereavement; Childhood Bereavement Network: London, UK, 2016; Available online: http://www.childhoodbereavementnetwork.org.uk/media/53767/Key-statistics-on-Childhood-Bereavement-Nov-2016.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Parsons, S. Long-Term Impact of Childhood Bereavement: Preliminary Analysis of the 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70); CWRC Working Paper; Childhood Wellbeing Research Centre: London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–22. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/long-term-impact-of-childhood-bereavement-preliminary-analysis-of-the-1970-british-cohort-study-bcs70 (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Bellis, M.A.; Hughes, K.; Leckenby, N.; Perkins, C.; Lowey, H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lewer, D.; King, E.; Bramley, G.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Treanor, M.; Maguire, N.; Bullock, M.; Hayward, A.; Story, A. The ACE Index: Mapping childhood adversity in England. J. Public Health 2019, 42, e487–e495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Palmer, M.; Saviet, M.; Tourish, J. Understanding and Supporting Grieving Adolescents and Young Adults. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 42, 275–281. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=c8h&AN=120221562&site=ehost-live (accessed on 29 January 2022). [PubMed]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Techniques of Grief Therapy: Assessment and Intervention; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, J.D.; Sparkes, A.C. Young people living with parental bereavement: Insights from an ethnographic study of a UK childhood bereavement service. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowdney, L. Children bereaved by parent or sibling death. Psychiatry 2008, 7, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFreniere, L.; Cain, A. Parentally Bereaved Children and Adolescents. Omega J. Death Dying 2015, 71, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, A.; Rantell, K.; Marston, L.; King, M.; Osborn, D. Perceived Stigma of Sudden Bereavement as a Risk Factor for Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempt: Analysis of British Cross-Sectional Survey Data on 3387 Young Bereaved Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergman, A.-S.; Axberg, U.; Hanson, E. When a parent dies—A systematic review of the effects of support programs for parentally bereaved children and their caregivers. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, C.A. Supporting the Grieving Adolescent: An Interview with a 21st Century Perspective. Prev. Res. 2011, 18, 14–17. Available online: http://web.b.ebscohost.com.proxy.cityu.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=ee18b076-694f-4f16-adec-e8c5f9867623%40sessionmgr113&vid=1&hid=125 (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Berg, L.; Rostila, M.; Hjern, A. Parental death during childhood and depression in young adults—A national cohort study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowdney, L. Annotation: Childhood Bereavement Following Parental Death. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2000, 41, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balk, D.E. Adolescent Development end Bereavement: An Introduction. PsycEXTRA Dataset 2011, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, R.; Kruse, J.; Hagl, M. A Meta-Analysis of Interventions for Bereaved Children and Adolescents. Death Stud. 2010, 34, 99–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chater, A. Let’s talk about death openly: When the world is grieving, please don’t walk on eggshells. The Psychologist 2020, 33, 23–25. Available online: https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/when-world-grieving-please-dont-walk-eggshells (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Williams, J. Investigating the role of physical activity following the death of a parent: The BABYSTEPS Project. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bedfordshire, Bedford, UK, 2021. Supervisory team: Chater, A.M. (Director of Studies), Zakrzewski-Fruer, J., Shorter, G., Howlett, N.. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. WHO and United Nations Definition of Adolescent. 2017. Available online: https://www.publichealth.com.ng/who-and-united-nations-definition-of-adolescent/#:~:text=The%20World%20Health%20Organization%20%28WHO%29%20and%20the%20United,the%20Convention%20on%20the%20Rights%20of%20the%20Child (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Rolls, L.; Relf, M. Bracketing interviews: Addressing methodological challenges in qualitative interviewing in bereavement and palliative care. Mortal 2006, 11, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- British Psychological Society. Code of Ethics and Conduct (BPS) 2018. Available online: https://www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/bps-code-ethics-and-conduct (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- QSR International. NVIVO 11. 2015. Available online: http://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/support-overview/downloads/nvivo-11-for-windows (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pusa, S.; Persson, C.; Sundin, K. Significant others’ lived experiences following a lung cancer trajectory—From diagnosis through and after the death of a family member. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 16, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crunk, A.E.; Burke, L.A.; Robinson, E.H.M. Complicated Grief: An Evolving Theoretical Landscape. J. Couns. Dev. 2017, 95, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høeg, B.L.; Johansen, C.; Christensen, J.; Frederiksen, K.; Dalton, S.O.; Dyregrov, A.; Bøge, P.; Dencker, A.; Bidstrup, P.E. Early parental loss and intimate relationships in adulthood: A nationwide study. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeffer, C.R.; Jiang, H.; Kakuma, T.; Hwang, J.; Metsch, M. Group Intervention for Children Bereaved by the Suicide of a Relative. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2002, 41, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Stroebe, M.; Chan, C.L.W.; Chow, A.Y.M. Guilt in Bereavement: A Review and Conceptual Framework. Death Stud. 2013, 38, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandler, I.N.; Ma, Y.; Tein, J.-Y.; Ayers, T.S.; Wolchik, S.; Kennedy, C.L.; Millsap, R. Long-term effects of the family bereavement program on multiple indicators of grief in parentally bereaved children and adolescents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 78, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kübler-Ross, E. On Death and Dying. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1972, 64, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobe, M.; Schut, H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Stud. 1999, 23, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digiacomo, M.; Lewis, J.; Nolan, M.T.; Phillips, J.; Davidson, P.M. Health transitions in recently widowed older women: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Lopez, S.J. Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive PsychologySnyder; Snyder, C.R.; Lopez, S.J. Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Davey, M.P.; Askew, J.; Godette, K. Parent and adolescent responses to non-terminal parental cancer: A retrospective multiple-case pilot study. Fam. Syst. Health 2003, 21, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, M.; Leopold, T. Changing Sibling Relationships After Parents’ Death: The Role of Solidarity and Kinkeeping. J. Marriage Fam. 2019, 81, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriessen, K.; Lobb, E.; Mowll, J.; Dudley, M.; Draper, B.; Mitchell, P.B. Help-seeking experiences of bereaved adolescents: A qualitative study. Death Stud. 2018, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, P.; Bulsara, C. “You either need help…you feel you don’t need help…or you don’t feel worthy of asking for it:” Receptivity to bereavement support. Palliat. Support. Care 2019, 17, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington-LaMorie, J.; Jordan, J.R.; Ruocco, K.; Cerel, J. Surviving families of military suicide loss: Exploring postvention peer support. Death Stud. 2018, 42, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, T.; Ford, A.; Templeton, L.; Valentine, C.; Velleman, R. Compassion or stigma? How adults bereaved by alcohol or drugs experience services. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, A.; Osborn, D.P.J.; Rantell, K.; King, M.B. The stigma perceived by people bereaved by suicide and other sudden deaths: A cross-sectional UK study of 3432 bereaved adults. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 87, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- You Matter. It’s OK Not to Be OK. 2016. Available online: https://youmatter.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/ok-not-ok/ (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- McFerran, K. Music Therapy with Bereaved Youth: Expressing Grief and Feeling Better. PsycEXTRA Dataset 2011, 18, 17–20. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/docview/964179291?accountid=15293%5Cnhttp://sfx.ub.edu/ub?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&genre=article&sid=ProQ:ProQ:ericshell&atitle=Music+Therapy+with+Bereaved+Youth:+Expressing+Grief+and+Feeling+ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Williams, J.; Shorter, G.W.; Howlett, N.; Zakrzewski-Fruer, J.; Chater, A.M. Can Physical Activity Support Grief Outcomes in Individuals Who Have Been Bereaved? A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Open 2021, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.; Sparkes, A.C. The meanings of outdoor physical activity for parentally bereaved young people in the United Kingdom: Insights from an ethnographic study. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2011, 11, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClatchey, I.S.; Wimmer, J.S. Healing Components of a Bereavement Camp: Children and Adolescents Give Voice to Their Experiences. Omega J. Death Dying 2012, 65, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chi, P.; Li, X.; Tam, C.C.; Zhao, G. Extracurricular interest as a resilience building block for children affected by parental HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2013, 26, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Langer, S. The Impact of Parental Bereavement on Young People: A Thematic Analysis of Using Online Web Forums as a Method of Coping. Omega J. Death Dying 2021, 00302228211024017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, M.; Yule, W.; Dyregrov, A.; Neshatdoost, H.; Ahmadi, S.J. Efficacy of Writing for Recovery on Traumatic Grief Symptoms of Afghani Refugee Bereaved Adolescents: A Randomized Control Trial. Omega J. Death Dying 2012, 65, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Age in Years (at Interview) | Parent Who Died | Cause of Death | Was Death Expected/Unexpected | Age in Years (at Death) | Years since Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marie | 39 | Dad | Illness | Unexpected | 20 | 18 |

| Ben | 33 | Dad | Natural | Unexpected | 18 | 16 |

| Rebekah | 25 | Mum | Illness | Unexpected | 16 | 9 |

| Laura | 21 | Mum | Illness | Unexpected | 11 | 9 |

| Jack | 25 | Dad | Unknown | Expected | 14 | 12 |

| Kate | 25 | Mum | Illness | Expected | 18 | 8 |

| Jim | 28 | Mum | Illness | Expected | 17 | 11 |

| Greg | Asked not to share | Dad | Illness | Unexpected | Asked not to share | Asked not to share |

| Zara | 41 | Mum | Illness | Expected | 23 | 17 |

| Adam | 30 | Mum | Illness | Unexpected | 13 | 16 |

| Chris | 28 | Dad | Illness | Expected | 21 | 7 |

| Claire | 40 | Mum | Illness | Unexpected | 22 | 17 |

| Louise | 28 | Dad | Illness | Unexpected | 13 | 15 |

| Gail | 38 | Dad | Illness | Unexpected | 24 | 13 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chater, A.M.; Howlett, N.; Shorter, G.W.; Zakrzewski-Fruer, J.K.; Williams, J. Reflections on Experiencing Parental Bereavement as a Young Person: A Retrospective Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042083

Chater AM, Howlett N, Shorter GW, Zakrzewski-Fruer JK, Williams J. Reflections on Experiencing Parental Bereavement as a Young Person: A Retrospective Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042083

Chicago/Turabian StyleChater, Angel Marie, Neil Howlett, Gillian W. Shorter, Julia K. Zakrzewski-Fruer, and Jane Williams. 2022. "Reflections on Experiencing Parental Bereavement as a Young Person: A Retrospective Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042083

APA StyleChater, A. M., Howlett, N., Shorter, G. W., Zakrzewski-Fruer, J. K., & Williams, J. (2022). Reflections on Experiencing Parental Bereavement as a Young Person: A Retrospective Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042083