Does the Formulation of the Decision Problem Affect Retirement?—Framing Effect and Planned Retirement Age

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review—Neoclassical and Behavioral Determinants of Retiring

2.1. The Neoclassical Approach to Retirement Decisions

2.2. Behavioral Determinants of Retirement Decisions

2.3. Framing Effect and the Decision to Retire

- : retirement at the age of (65 years) entails a retirement pension of . Earlier or later retirement will result in a decrease or increase in this benefit by amount X for each year of difference. At what age to retire?

- : retirement at the age (66 years) entails a pension greater by G, than in the case of retiring at age . At what age to retire?

- : retirement at age (65 years) entails a pension reduced by L, less than in the case of retiring at age . At what age to retire?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Hypothesis

3.2. Planned Retirement Age and Decision to Retire

- According to the type of income criterion, a pensioner is a person who receives a retirement benefit.

- According to the event criterion, a pensioner is a person who has partially or completely reduced the supply of his work or changed its nature.

- According to the age criterion, the population of pensioners includes people who have exceeded a certain metric age.

- According to the declarative criterion, a pensioner is a person who defines himself as a pensioner.

3.3. Research Procedure and Research Questionnaire

“Experts are currently discussing the assumptions of a completely new proposal for a pension system. This new pension system will give you the opportunity to decide freely regarding the moment of leaving your job and starting to receive your pension. In the proposed pension system, if you pay contributions to the pension system throughout the entire period of work and retire at the standard retirement age (the age is assumed to be {65 years}), the amount of the pension will be about {40%} of your last gross salary. Retiring one year before the standard retirement age will mean about 10% lower retirement benefits for the rest of your life for each year of shorter work. Similarly, retiring one year after reaching the standard retirement age will entail about 10% higher pension for each additional year of work.”

3.4. Scope of the Research

3.5. Data

4. Results

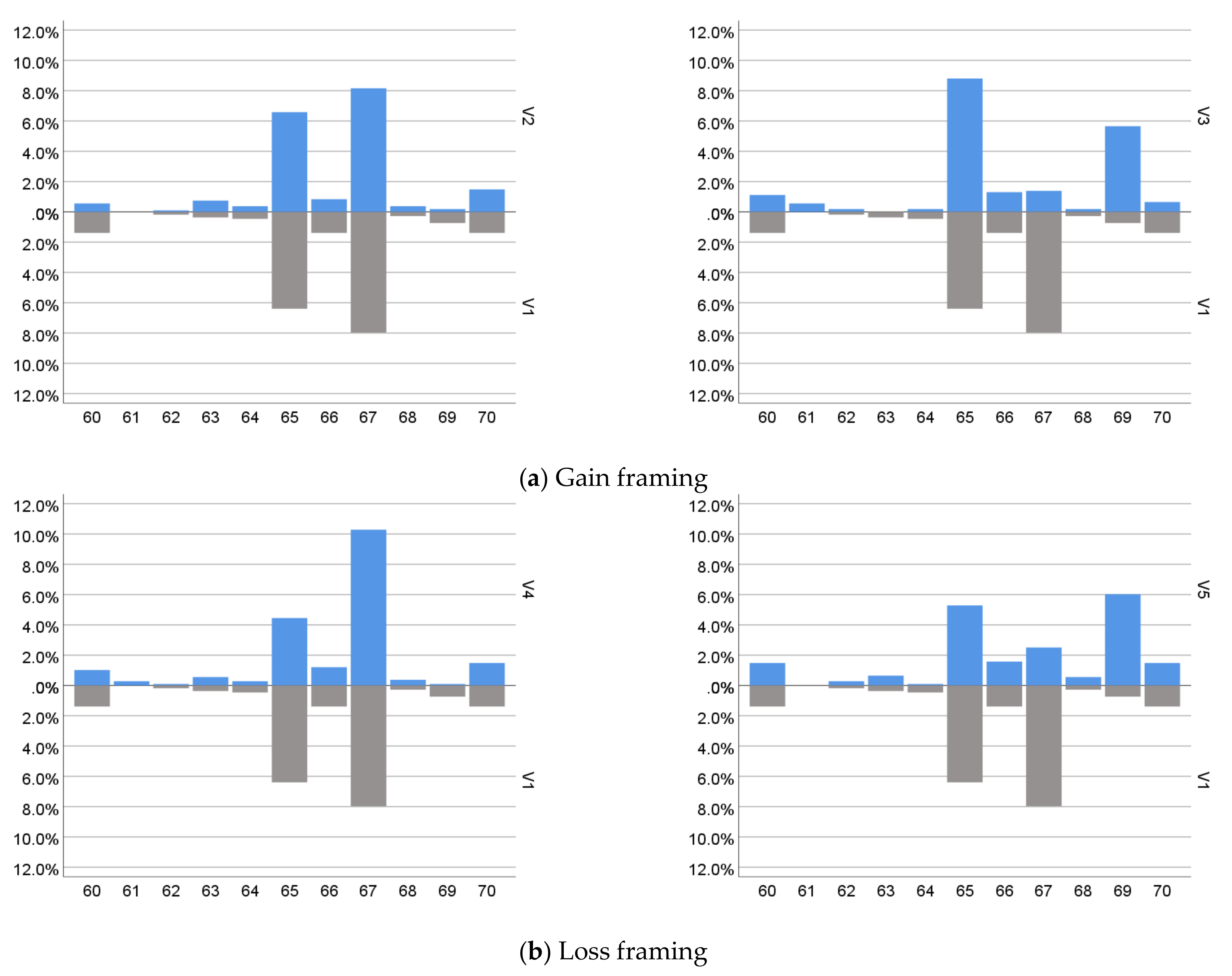

- Compared to the groups presented with a neutral variant of the question (V1), respondents who read the questions taking into account one of the framing options, indicated on average a 3 month higher planned retirement age.

- Comparison of answers to questions with loss framing (V2 and V3) with questions with gain framing (V4 and V5) indicates that highlighting losses in the question leads to a slightly higher planned retirement age (66 years and 4 months and 66 years and 1 month, respectively).

- Comparing the answers to questions taking into account narrow (V2 and V4) and wide (V3 and V5) framing did not give unambiguous results. On the one hand, both variants of gain framing have produced similar results: extending the planned retirement age by about 2 months. On the other hand, the difference between the loss framing options was significant: the narrow framework led to an extension of the planned retirement age by 2 months, while the wide one was by 7 months.

- means that, in comparison with the reference value, the given value of the independent variable increases the odds of the occurrence of the analyzed phenomenon;

- means that, in comparison with the reference value, the given value of the independent variable decreases the odds of the occurrence of the analyzed phenomenon;

- means that, in comparison with the reference value, the given value of the independent variable does not change the odds of the occurrence of the analyzed phenomenon.

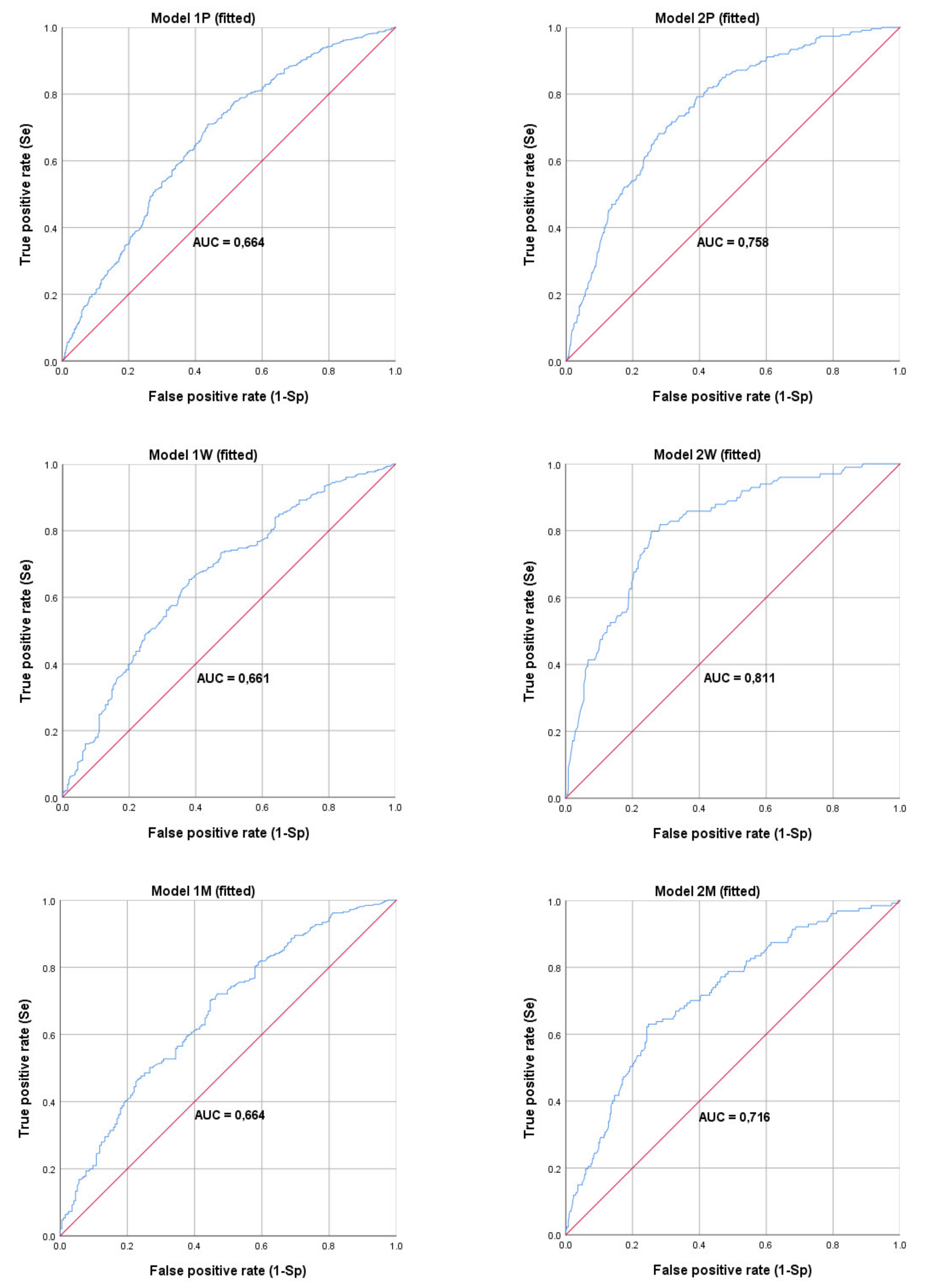

- Over 65 years of age—analysis 1,

- Over 67 years—analysis 2,

- Both in model 1P and 2P, the variable significantly influencing the planned retirement age was gender. If the respondent was male, the odds of indicating the retirement age above 65 years increased by 85%, and the odds of indicating the retirement age above 67 years increased by 125%.

- A factor influencing the planned retirement age was the age of the respondent. In each model (both the total population and for women and men studied separately), the values of odds ratios indicated that an increase in the age of the subject by one year caused a decrease in the odds of retirement above the age taken into account in a given model (this value fluctuated in the range of 4–5%). The older the person was (and the closer they were to actual retirement), the less willing they were to prolong their professional activity. As potential explanations for this relationship, one can point to changing external conditions, changes in the mentality of the subjects as well as the phenomenon of hyperbolic discounting discussed in behavioral economics [141,142]. However, a full explanation of the identified relationship requires further research.

- Better education was associated with greater chances of indicating a higher retirement age. The effect of education was stronger in the case of men. For example, compared to men with primary education, men with higher education had 3.42 times higher odds to indicate the planned retirement age over 65, and 3.88 times higher odds to indicate the planned retirement age above 67. The respective values for women were 2.51 and 2.03. This observation proves the key role of broadly understood education in stimulating the extension of professional activity.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question Variant | Exact Wording of the Question |

|---|---|

| Male Respondents | |

| V1 | Jan is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. He learned that if he retires at 65 years he will receive a benefit of 2000 PLN net per month (paid for life). If he decides to retire at the age of 63 years he will receive a benefit lower by approx. 350 PLN (1650 PLN). If he decides to retire at the age of 67 years, he will receive a benefit higher by approx. 420 PLN (2420 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Jan’s place? |

| V2 | Jan is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. He learned that if he retires at 63 years he will receive a benefit of 1650 PLN net per month (paid for life). If he decides to retire at the age of 65 years he will receive a benefit higher by approx. 350 PLN (2000 PLN). If he decides to retire at the age of 67 years, he will receive a benefit higher by approx. 770 PLN (2420 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Jan’s place? |

| V3 | Jan is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. He learned that if he retires at 61 years he will receive a benefit of 1370 PLN net per month (paid for life). If he decides to retire at the age of 65 years he will receive a benefit higher by approx. 630 PLN (2000 PLN). If he decides to retire at the age of 69 years, he will receive a benefit higher by approx. 1560 PLN (2930 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Jan’s place? |

| V4 | Jan is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. He learned that if he retires at 67 years he will receive a benefit of 2420 PLN net per month (paid for life). If he decides to retire at the age of 65 years he will receive a benefit lower by approx. 420 PLN (2000 PLN). If he decides to retire at the age of 63 years, he will receive a benefit lower by approx. 770 PLN (1650 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Jan’s place? |

| V5 | Jan is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. He learned that if he retires at 69 years he will receive a benefit of 2930 PLN net per month (paid for life). If he decides to retire at the age of 65 years he will receive a benefit lower by approx. 930 PLN (2000 PLN). If he decides to retire at the age of 61 years, he will receive a benefit lower by approx. 1560 PLN (1370 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Jan’s place? |

| Female Respondents | |

| V1 | Barbara is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. She learned that if she retires at 65 years she will receive a benefit of 2000 PLN net per month (paid for life). If she decides to retire at the age of 63 years she will receive a benefit lower by approx. 350 PLN (1650 PLN). If she decides to retire at the age of 67 years, she will receive a benefit higher by approx. 420 PLN (2420 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Barbara’s place? |

| V2 | Barbara is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. She learned that if she retires at 63 years she will receive a benefit of 1650 PLN net per month (paid for life). If she decides to retire at the age of 65 years she will receive a benefit higher by approx. 350 PLN (2000 PLN). If she decides to retire at the age of 67 years, she will receive a benefit higher by approx. 770 PLN (2420 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Barbara’s place? |

| V3 | Barbara is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. She learned that if she retires at 61 years she will receive a benefit of 1370 PLN net per month (paid for life). If she decides to retire at the age of 65 years she will receive a benefit higher by approx. 630 PLN (2000 PLN). If she decides to retire at the age of 69 years, she will receive a benefit higher by approx. 1560 PLN (2930 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Barbara’s place? |

| V4 | Barbara is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. She learned that if she retires at 67 years she will receive a benefit of 2420 PLN net per month (paid for life). If she decides to retire at the age of 65 years she will receive a benefit lower by approx. 420 PLN (2000 PLN). If she decides to retire at the age of 63 years, she will receive a benefit lower by approx. 770 PLN (1650 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Barbara’s place? |

| V5 | Barbara is considering when it is best to retire in the proposed pension system. She learned that if she retires at 69 years she will receive a benefit of 2930 PLN net per month (paid for life). If she decides to retire at the age of 65 years she will receive a benefit lower by approx. 930 PLN (2000 PLN). If she decides to retire at the age of 61 years, she will receive a benefit lower by approx. 1560 PLN (1370 PLN). At what age would you have retired in Barbara’s place? |

Appendix B

| Scenario | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||||

| N | 222 | 209 | 216 | 217 | 215 |

| Mean | 65,94 | 66,11 | 66,10 | 66,13 | 66,51 |

| Standard deviation | 2.24 | 1.92 | 2.55 | 2.14 | 2.72 |

| Men | |||||

| N | 104 | 98 | 100 | 107 | 101 |

| Mean | 66.41 | 66.55 | 66.26 | 66.34 | 66.78 |

| Standard deviation | 2.10 | 1.75 | 2.60 | 2.22 | 2.50 |

| Women | |||||

| N | 118 | 111 | 116 | 110 | 114 |

| Mean | 65.53 | 65.72 | 65.96 | 65.94 | 66.27 |

| Standard deviation | 2.28 | 1.99 | 2.51 | 2.05 | 2.89 |

| Variable | Model 1W | Model 2W | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (>65 Years) | (>67 Years) | |||||||||

| β | SE β | OR | Sig. | 95% CI for OR | β | SE β | OR | Sig. | 95% CI for OR | |

| Framing effect (ref.: V1 (neutral)) | ** | *** | ||||||||

| – V2 (gain, narrow) | −0.07 | 0.27 | 0.93 | 0.54–1.58 | 0.04 | 0.60 | 1.04 | 0.32–3.35 | ||

| – V3 (gain, broad) | −0.44 | 0.27 | 0.65 | 0.37–1.09 | 2.12 | 0.47 | 8.35 | *** | 3.31–21.0 | |

| – V4 (loss, narrow) | 0.57 | 0.28 | 1.76 | ** | 1.01–3.06 | −0.12 | 0.62 | 0.89 | 0.26–3.01 | |

| – V5 (loss, broad) | 0.05 | 0.27 | 1.05 | 0.61–1.79 | 2.66 | 0.47 | 14.27 | *** | 5.73–35.5 | |

| Age (continuous variable) | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.95 | *** | 0.92–0.97 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.95 | ** | 0.90–0.98 |

| Education (ref.: primary) | *** | * | ||||||||

| – secondary | 0.59 | 0.22 | 1.80 | *** | 1.16–2.79 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 1.21 | 0.61–2.36 | |

| – higher | 0.92 | 0.24 | 2.51 | *** | 1.56–4.01 | 0.71 | 0.35 | 2.03 | ** | 1.02–3.99 |

| Marital status (ref.: without a partner) | −0.36 | 0.20 | 0.70 | * | 0.46–1.03 | Variable not included in the model | ||||

| Constant | 2.35 | 0.81 | 10.48 | *** | −0.66 | 1.16 | 0.52 | |||

| Significance of the model | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| −2 Log likelihood | 739.78 | 416.13 | ||||||||

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.077 | 0.176 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.103 | 0.291 | ||||||||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p-value) | 0.356 | 0.833 | ||||||||

| Variable | Model 1M | Model 2M | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (>65 Years) | (>67 Years) | |||||||||

| β | SE β | OR | Sig. | 95% CI for OR | β | SE β | OR | Sig. | 95% CI for OR | |

| Framing effect (ref.: V1 (neutral)) | * | *** | ||||||||

| – V2 (gain, narrow) | 0.02 | 0.30 | 1.02 | 0.56–1.85 | −0.27 | 0.38 | 0.76 | 0.36–1.60 | ||

| – V3 (gain, broad) | −0.54 | 0.30 | 0.58 | * | 0.32–1.03 | 0.88 | 0.34 | 2.41 | *** | 1.24–4.65 |

| – V4 (loss, narrow) | 0.16 | 0.30 | 1.17 | 0.65–2.11 | −0.41 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 0.31–1.39 | ||

| – V5 (loss, broad) | 0.19 | 0.31 | 1.21 | 0.66–2.19 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 2.47 | *** | 1.28–4.73 | |

| Age (continuous variable) | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.96 | ** | 0.93–0.99 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.96 | ** | 0.92–0.99 |

| Education (ref.: primary) | *** | *** | ||||||||

| – secondary | 0.79 | 0.23 | 2.21 | *** | 1.39–3.48 | 0.93 | 0.31 | 2.54 | *** | 1.38–4.65 |

| – higher | 1.23 | 0.26 | 3.42 | *** | 2.04–5.72 | 1.36 | 0.32 | 3.88 | *** | 2.07–7.25 |

| Health condition (ref.: bad) | Variable not included in the model | * | ||||||||

| – average | 0.52 | 0.35 | 1.68 | 0.84–3.31 | ||||||

| – good | 0.03 | 0.36 | 1.03 | 0.51–2.08 | ||||||

| Number of children (ref. 0) | * | Variable not included in the model | ||||||||

| – 1 | −0.44 | 0.28 | 0.64 | 0.36–1.12 | ||||||

| – 2 | −0.56 | 0.26 | 0.57 | ** | 0.33–0.95 | |||||

| – 3 or more | −0.76 | 0.34 | 0.47 | ** | 0.23–0.91 | |||||

| Constant | 2.21 | 0.96 | 9.10 | ** | −0.26 | 1.11 | 0.77 | |||

| Significance of the model | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| −2 Log likelihood | 635.30 | 516.47 | ||||||||

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.081 | 0.104 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.110 | 0.154 | ||||||||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p-value) | 0.229 | 0.940 | ||||||||

Appendix C

| Model | Accuracy (Ac) [%] | Specificity (Sp) [%] | Sensitivity (Se) [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1P | 64.4 | 42.6 | 80.5 |

| 2P | 78.8 | 96.0 | 13.7 |

| 1W | 62.7 | 53.2 | 70.9 |

| 2W | 83.8 | 97.9 | 17.2 |

| 1M | 65.7 | 33.3 | 85.7 |

| 2M | 75.3 | 94.0 | 18.9 |

References

- OECD. Pensions at a Glance 2019: OECD and G20 Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Modigliani, F.; Brumberg, R. Utility Analysis and the Consumption Function: An Interpretation of Cross-Section Data. In Post Keynesian Economics; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1954; pp. 388–436. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. The Permanent Income Hypothesis. In A Theory of the Consumption Function; National Bureau of Economic Research General Series; Princeton Univ. Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1957; pp. 20–37. ISBN 978-0-691-13886-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, A.; Modigliani, F. The “Life Cycle” Hypothesis of Saving: Aggregate Implications and Tests. Am. Econ. Rev. 1963, 53, 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, N.; Diamond, P. Reformy Systemu Emerytalnego, Krótki Przewodnik; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; ISBN 978-83-88700-76-7. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, D. Pension Economics; John Willey & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-470-05844-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Choices, Values, and Frames. Am. Psychol. 1984, 39, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. Toward a Positive Theory of Consumer Choice. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1980, 1, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. Mental Accounting and Consumer Choice. Mark. Sci. 1985, 4, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, P. Regulatory Policy and Behavioural Economics; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Camerer, C.F.; Loewenstein, G. Behavioral Economics: Past, Present, Future. In Advances in Behavioral Economics; Camerer, C.F., Loewenstein, G., Rabin, M., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 3–52. ISBN 978-0-691-11682-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, O.; Utkus, S. Pension Design and Structure: New Lessons from Behavioral Finance; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-19-160167-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, C.B. The Economics of the Retirement Decisions. In Retirement: Reasons, Process and Results; Adams, G.A., Beehr, T.A., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lazear, E.P. Retirement from the Labor Force. In Handbook of Labor Economics; Ashenfelter, O.C., Layard, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; Volume 1, pp. 305–355. [Google Scholar]

- Lumsdaine, R.L.; Mitchell, O.S. New Developments in the Economic Analysis of Retirement. In Handbook of Labour Economics; Ashenfelter, O.C., Card, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 3C. [Google Scholar]

- Boskin, M.J. Social Security and Retirement Decisions. Econ. Inq. 1977, 15, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskin, M.J.; Hurd, M.D. The Effect of Social Security on Early Retirement. J. Public Econ. 1978, 10, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, V.P.; Lilien, D.M. Social Security and the Retirement Decision. Q. J. Econ. 1981, 96, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammartino, F. The Effect of Health on Retirement. Soc. Secur. Bull. 1987, 50, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, J.F. Microeconomic Determinants of Early Retirement: A Cross-Sectional View of White Married Men. J. Hum. Resour. 1977, 12, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.H.; Blinder, A.S. Market Wages, Reservation Wages, and Retirement Decisions. J. Public Econ. 1980, 14, 277–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, G.; Mitchell, O. Economic Determinants of the Optimal Retirement Age: An Empirical Investigation. J. Hum. Resour. 1984, 19, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, O.; Fields, G. The Economics of Retirement Behavior. J. Labor Econ. 1984, 2, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MaCurdy, T.E. An Empirical Model of Labor Supply in a Life-Cycle Setting. J. Political Econ. 1981, 89, 1059–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustman, A.L.; Steinmeier, T.L. A Structural Retirement Model. Econometrica 1986, 54, 555–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.H.; Wise, D.A. Pensions, the Option Value of Work, and Retirement. Econometrica 1990, 58, 1151–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.H.; Wise, D.A. The Pension Inducement to Retire: An Option Value Analysis. In Issues in the Economics of Aging; Wise, D.A., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Lumsdaine, R.L.; Stock, J.H.; Wise, D.A. Retirement Incentives: The Interaction between Employer-Provided Pensions, Social Security, and Retiree Health Benefits; NBER Working Paper Series, No. 4613; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samwick, A.A. New Evidence on Pensions, Social Security, and the Timing of Retirement. J. Public Econ. 1998, 70, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovec, J.; Stern, S. Job Exit Behavior of Older Men. Econometrica 1991, 59, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daula, T.; Moffitt, R. Estimating Dynamic Models of Quit Behavior: The Case of Military Reenlistment. J. Labor Econ. 1995, 13, 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rust, J.; Phelan, C. How Social Security and Medicare Affect Retirement Behavior In a World of Incomplete Markets. Econometrica 1997, 65, 781–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, N.; Vermeulen, F. The Impact of an Increase in the Legal Retirement Age on the Effective Retirement Age. Economist 2014, 162, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirregabiria, V. Another Look at the Identification of Dynamic Discrete Decision Processes: An Application to Retirement Behavior. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2010, 28, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyma, A. A Structural Dynamic Analysis of Retirement Behaviour in the Netherlands. J. Appl. Econom. 2004, 19, 739–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, J.P. A Dynamic Programming Model of Retirement Behavior. In The Economics of Aging; Wise, D.A., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989; pp. 359–404. [Google Scholar]

- Scharn, M.; Sewdas, R.; Boot, C.R.L.; Huisman, M.; Lindeboom, M.; van der Beek, A.J. Domains and Determinants of Retirement Timing: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.G.; Chaffee, D.S.; Sonnega, A. Retirement Timing: A Review and Recommendations for Future Research. Work Aging Retire 2016, 2, 230–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhauser, R.V. The Pension Acceptance Decision of Older Workers. J. Hum. Resour. 1979, 14, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustman, A.L.; Mitchell, O.S.; Steinmeier, T.L. The Role of Pensions in the Labor Market: A Survey of the Literature. ILR Rev. 1994, 47, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, G.; Mitchell, O. The Effects of Social Security Reforms on Retirement Ages and Retirement Incomes. J. Public Econ. 1984, 25, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- French, E. The Effects of Health, Wealth, and Wages on Labour Supply and Retirement Behaviour. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2005, 72, 395–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, A.; Vonkova, H. How Sensitive Are Retirement Decisions to Financial Incentives? A Stated Preference Analysis. J. Appl. Econom. 2014, 29, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.; Emmerson, C.; Tetlow, E. Healthy Retirement or Unhealthy Activity: How Important Are Financial Incentives in Explaining Retirement? J. Public Econ. 2007, 89, 427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Euwals, R.; van Vuuren, D.; Wolthoff, R. Early Retirement Behaviour in the Netherlands: Evidence from a Policy Reform. Economist 2010, 158, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bloemen, H.G. The Effect of Private Wealth on the Retirement Rate: An Empirical Analysis. Economica 2011, 78, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtless, G. Social Security, Unanticipated Benefit Increases, and the Timing of Retirement. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1986, 53, 781–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustman, A.L.; Steinmeier, T.L. The Social Security Early Entitlement Age in a Structural Model of Retirement and Wealth. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöndal, S.; Scarpetta, S. The Retirement Decision in OECD Countries; OECD: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borella, M.; Moscarola, F.C. Microsimulation of Pension Reforms: Behavioural versus Nonbehavioural Approach; CeRP Working Papers; Center for Research on Pensions and Welfare Policies: Turin, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Staubli, S.; Zweimüller, J. Does Raising the Early Retirement Age Increase Employment of Older Workers? J. Public Econ. 2013, 108, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrobuoni, G. Labor Supply Effects of the Recent Social Security Benefit Cuts: Empirical Estimates Using Cohort Discontinuities. J. Public Econ. 2009, 93, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, M.; Wilke, C.B. At What Age Do You Expect to Retire? Retirement Expectations and Increases in the Statutory Retirement Age. Fisc. Stud. 2014, 35, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grip, A.; Fouarge, D.; Montizaan, R. How Sensitive Are Individual Retirement Expectations to Raising the Retirement Age? Economist 2013, 161, 225–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, C.R.L.; Scharn, M.; van der Beek, A.J.; Andersen, L.L.; Elbers, C.T.M.; Lindeboom, M. Effects of Early Retirement Policy Changes on Working until Retirement: Natural Experiment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, M.; Hofer, H.; Wögerbauer, B. Determinants for the Transition from Work into Retirement in Europe. IZA J. Eur. Labor Stud. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpansalo, M.; Manninen, P.; Kauhanen, J.; Lakka, T.A.; Salonen, J.T. Perceived Health as a Predictor of Early Retirement. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2004, 30, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robroek, S.J.W.; Schuring, M.; Croezen, S.; Stattin, M.; Burdorf, A. Poor Health, Unhealthy Behaviors, and Unfavorable Work Characteristics Influence Pathways of Exit from Paid Employment among Older Workers in Europe: A Four Year Follow-up Study. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2013, 39, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wind, A.; Geuskens, G.A.; Ybema, J.F.; Blatter, B.M.; Burdorf, A.; Bongers, P.M.; van der Beek, A.J. Health, Job Characteristics, Skills, and Social and Financial Factors in Relation to Early Retirement—Results from a Longitudinal Study in the Netherlands. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2014, 40, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, S.; Shultz, K.S. Antecedents of Bridge Employment: A Longitudinal Investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, A.; Sundstrup, E.; Andersen, L.L. Factors Contributing to Retirement Decisions in Denmark: Comparing Employees Who Expect to Retire before, at, and after the State Pension Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Solinge, H.; Henkens, K. Living Longer, Working Longer? The Impact of Subjective Life Expectancy on Retirement Intentions and Behaviour. Eur. J. Public Health 2010, 20, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, M.D.; Smith, J.P.; Zissimopoulos, J.M. The Effects of Subjective Survival on Retirement and Social Security Claiming. J. Appl. Econom. 2004, 19, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J.; Wahrendorf, M.; von dem Knesebeck, O.; Jürges, H.; Börsch-Supan, A. Quality of Work, Well-Being, and Intended Early Retirement of Older Employees: Baseline Results from the SHARE Study. Eur J. Public Health 2007, 17, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blekesaune, M.; Solem, P.E. Working Conditions and Early Retirement: A Prospective Study of Retirement Behavior. Res. Aging 2005, 27, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J.; Moodie, S.; Dolan, S.L.; Fiksenbaum, L. Job Demands, Social Support, Work Satisfaction and Psychological Well-Being Among Nurses in Spain; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barslund, M.; Bauknecht, J.; Cebulla, A. Working Conditions and Retirement: How Important Are HR Policies in Prolonging Working Life? Manag. Rev. Socio Econ. Stud. 2019, 30, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B.; Korunka, C.; Hoonakker, P.; Raymo, J.M. Work and Family Characteristics as Predictors of Early Retirement in Married Men and Women. Res. Aging 2010, 32, 467–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A.; Glazer, S.; Nielson, N.L.; Farmer, S.J. Work and Nonwork Predictors of Employees’ Retirement Ages. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 57, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalto, C.P.; Yuh, Y.; Hanna, S. Determinants of Planned Retirement Age. Financ. Serv. Rev. 2000, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, J.; De Winter, T. Becoming a Grandparent and Early Retirement in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 29, 1295–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kridahl, L. Retirement Timing and Grandparenthood: A Population-Based Study on Sweden. Demogr. Res. 2017, 37, 957–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, R. Retirement Behaviour in OECD Countries: Impact of Old-Age Pension Schemes and Other Social Transfer Programmes. OECD Econ. Stud. 2004, 2003, 7–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coile, C.; Levine, P. The Market Crash and Mass Layoffs: How the Current Economic Crisis May Affect Retirement. B.E. J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2011, 11, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmora, P.; Ritter, M. Unemployment and the Retirement Decisions of Older Workers. J. Labor Res. 2015, 36, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, J.L.; Perozek, M.G. Wealth Effects and the Consumption of Leisure: Retirement Decisions during the Stock Market Boom of the 1900s. Available online: https://fedinprint.org/item/fedgfe/34261/original (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Gustman, A.L.; Steinmeier, T.L.; Tabatabai, N. What the Stock Market Decline Means for the Financial Security and Retirement Choices of the Near-Retirement Population; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McFall, B. Crash and Wait? The Impact of the Great Recession on the Retirement Plans of Older Americans. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B. Too Poor to Retire? Housing Prices and Retirement. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2018, 27, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chybalski, F. Wiek Emerytalny z Perspektywy Ekonomicznej. Studium Teoretyczno-Empiryczne; Wydawnictwo C.H. Beck: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sarabia-Cobo, C.M.; Pérez, V.; Hermosilla, C.; de Lorena, P. Retirement or No Retirement? The Decision’s Effects on Cognitive Functioning, Well-Being, and Quality of Life. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedynak, T. Behawioralne Uwarunkowania Decyzji o Przejściu Na Emeryturę; C.H. Beck: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. The Role of Conventional Retirement Age in Retirement Decisions. SSRN J. 2006, WP 2006-120, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vermeer, N. Age Anchors and the Expected Retirement Age: An Experimental Study. Economist 2016, 164, 255–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrian, B.; Shea, D.F. The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 1149–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.J.; Laibson, D.; Madrian, B.C. Why Does the Law of One Price Fail? An Experiment on Index Mutual Funds. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 1405–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, F.; Hastings, J. Fettered Consumers and Sophisticated Firms: Evidence from Mexico’s Privatized Social Security Market; NBER Working Paper Series, No 18582; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.; Stevens, A.H. What You Don’t Know Can’t Help You: Pension Knowledge and Retirement Decision-Making. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2008, 90, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erp, F.; Vermeer, N.; van Vuuren, D. Non-Financial Determinants of Retirement: A Literature Review. Economist 2014, 162, 167–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, N.; van Rooij, M.; van Vuuren, D. Retirement Age Preferences: The Role of Social Interactions and Anchoring at the Statutory Retirement Age. Economist 2019, 167, 307–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernheim, B.D.; Skinner, J.; Weinberg, S. What Accounts for the Variation in Retirement Wealth among U.S. Households? Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 832–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopczuk, W.; Song, J. Stylized Facts and Incentive Effects Related to Claiming of Retirement Benefits Based on Social Security Administration Data; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Knoll, M. Behavioral and Psychological Aspects of the Retirement Decision; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Benartzi, S.; Thaler, R. Naive Diversification Strategies in Defined Contribution Saving Plans. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Laibson, D.; Madrian, B.C.; Metrick, A. Defined Contribution Pensions: Plan Rules, Participant Choices, and the Path of Least Resistance. Tax Policy Econ. 2002, 16, 67–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benartzi, S.; Thaler, R. How Much Is Investor Autonomy Worth? J. Financ. 2002, 57, 1593–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.; Benartzi, S. Save More TomorrowTM: Using Behavioral Economics to Increase Employee Saving. J. Political Econ. 2004, 112, 164–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benartzi, S.; Thaler, R. Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Savings Behavior. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Laibson, D.; Madrian, B. Reducing the Complexity Costs of 401(k) Participation Through Quick Enrollment. In Developments in the Economics of Aging; Wise, D., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Beshears, J.; Choi, J.; Laibson, D.; Madrian, B. Simplification and Saving. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2013, 95, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ko, D.; Choe, H. Classifying Retirement Preparation Planners and Doers: A Multi-Country Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Kling, J.R.; Mullainathan, S.; Wrobel, M.V. Why Don’t People Insure Late-Life Consumption? A Framing Explanation of the Under-Annuitization Puzzle. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.; Boardman, T. Spend More Today Safely: Using Behavioral Economics to Improve Retirement Expenditure Decisions With SPEEDOMETER Plans. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2014, 17, 83–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Laibson, D.; Madrian, B.; Metrick, A. For Better or for Worse: Default Effects and 401(k) Savings Behavior; NBER Working Paper Series, No 8651; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Laibson, D.; Madrian, B.; Metrick, A. Perspectives in the Economics of Aging; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fetherstonhaugh, D.; Ross, L. Framing Effects and Income Flow Preferences in Decisions about Social Security. In Behavioral Dimensions of Retirement Economics; Brookings Institution Press and Russell Sage Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Liebman, J.B.; Luttmer, E.F.P. The Perception of Social Security Incentives for Labor Supply and Retirement: The Median Voter Knows More Than You’d Think. Tax Policy Econ. 2012, 26, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebman, J.B.; Luttmer, E.F.P. Would People Behave Differently If They Better Understood Social Security? Evidence from a Field Experiment. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2015, 7, 275–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behaghel, L.; Blau, D. Framing Social Security Reform: Behavioral Responses to Changes in the Full Retirement Age. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2012, 4, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Kapteyn, A.; Mitchell, O.S. Framing and Claiming: How Information-Framing Affects Expected Social Security Claiming Behavior. J. Risk Insur. 2016, 83, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E.; Saez, E. The Role of Information and Social Interactions in Retirement Plan Decisions: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2003, 118, 815–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gächter, S.; Orzen, H.; Renner, E.; Starmer, C. Are Experimental Economists Prone to Framing Effects? A Natural Field Experiment. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2009, 70, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Druckman, J.N. Using Credible Advice to Overcome Framing Effects. J. Law Econ. Organ. 2001, 17, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibas, S. Plea Bargaining Outside the Shadow of Trial. Harv. Law Rev. 2004, 117, 2463–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.M. Effects of Framing and Level of Probability on Patients’ Preferences for Cancer Chemotherapy. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1989, 42, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. Fiscal Transparency and Public Service Quality Association: Evidence from 12 Coastal Provinces and Cities of China. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Li, Q.; Yu, S. Persuasive Effects of Message Framing and Narrative Format on Promoting COVID-19 Vaccination: A Study on Chinese College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benartzi, S.; Thaler, R. Risk Aversion or Myopia? Choices in Repeated Gambles and Retirement Investments. Manag. Sci. 1999, 45, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, C.; Schreiber, P.; Weber, M. Framing and Retirement Age: The Gap between Willingness-to-Accept and Willingness-to-Pay. Econ. Policy 2017, 32, 757–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchett, D. The Impact of Retirement Age Uncertainty on Required Retirement Savings. J. Financ. Plan. 2018, 31, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, F.T.; Spencer, B.G. What Is Retirement? A Review and Assessment of Alternative Concepts and Measures. Can. J. Aging/La Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 2009, 28, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek, A.; Kapteyn, A.; Gray, A. Using Vignettes to Improve Understanding of Social Security and Annuities; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wason, K.D.; Polonsky, M.J.; Hyman, M.R. Designing Vignette Studies in Marketing. Australas. Mark. J. 2002, 10, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A. To Retire or Not to Retire: That Is Not the Question. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple Comparisons among Means. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1961, 56, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; p. 779. ISBN 978-0-7619-4452-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zickar, M.J.; Gibby, R.E. Data Analytic Techniques for Retirement Research. In Retirement: Reasons, Processes, and Results; Adams, G.A., Beehr, T.A., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-8261-2054-0. [Google Scholar]

- Olejnik, I. Intention to continue professional work after reaching retirement age and its determinants. Ekonometria 2017, 2, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ruzik-Sierdzińska, A. An Attempt to Identify Factors Influencing Retirement Decisions in Poland. Acta Univ. Lodziensis Folia Oeconomica 2018, 4, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielawska, K. Economic Activity of Polish Pensioners in the Light of Quantitative Research. Equilibrium 2019, 14, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisz, A. Przystępny Kurs Statystyki z Zastosowaniem STATISTICA PL Na Przykładach z Medycyny. Tom 2. Modele Liniowe i Nieliniowe; StatSoft Polska: Kraków, Poland, 2007; ISBN 978-83-88724-30-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bazyl, M.; Gruszczyński, M.; Książek, M.; Owczaruk, M.; Szulc, A.; Wisniowski, A.; Witkowski, B. Mikroekonometria. Modele i Metody Analizy Danych Indywidualnych; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Menard, S. Applied Logistic Regression; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maddala, G.S. Ekonometria; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet, S.; Grace-Martin, K. Data Analysis with SPSS. A First Course in Applied Statistics; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R. Applied Logistic Regression; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Danieluk, B. Zastosowanie Regresji Logistycznej w Badaniach Eksperymentalnych. Psychol. Społeczna 2010, 5, 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Laibson, D. Golden Eggs and Hyperbolic Discounting. Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 443–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, S.; Loewenstein, G.; O’Donoghue, T. Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review. J. Econ. Lit. 2002, 40, 351–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behavioral Factor | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Framing effect | In the case of decisions on retirement, the framing effect is the impact of how the decision-making situation is presented on the choices of decision-makers regarding their actual or planned (declared) retirement age. |

| Default option | A standard choice for which no additional action is required. It is a decision that requires the least analysis and intellectual effort. The person deciding on the default option is satisfied with the consequences of this option and is not looking for the optimal solution, in terms of cost–benefit analysis. In the context of the decision to retire, a typical default option is a general retirement age. |

| Anchoring effect | Influencing pension decisions by values that are deeply rooted in the consciousness of policymakers and are important for retirement (age anchors) [87]. Such values are legal figures that persist for many years, such as the minimum or general retirement age. |

| Impact of social norms and social environment | The influence of other people’s opinions, beliefs and experiences on the decisions made. It may be direct or indirect: direct influence consists of the influence of the immediate environment (family, friends, co-workers, superiors). Within this channel of influence, individuals learn from each other through discussions or by drawing conclusions from actions taken by others; indirect influence consists of the influence of abstract norms that are common in larger social groups. Individuals try to act in such a way that, after the end of professional activity, they maintain a similar level of consumption to that which is common in their social group [114]. |

| Hyperbolic discounting | Perceiving future benefits well below their real value and overestimating the value of benefits offered immediately. This phenomenon explains why people who initially planned to retire later actually retire near the statutory retirement age. |

| Planning fallacy | Erroneous prediction of future events as a result of the unrealistic (excessively optimistic) construction of mental scenarios that the individual creates to predict the future. When considering retirement, people analyze only the best scenarios (they do not take into account negative random events such as illness or death of a partner), which makes them willing to retire earlier and accept lower retirement benefits. |

| Affective forecasting | People’s tendency to imagine that a given event in the future will be better (or worse) than it later turns out. M. Knoll transferred onto pension economics the concept of affective forecasting [96]. She argued that this phenomenon leads individuals to prefer early retirement, as people tend to imagine that retirement will bring them more satisfaction than it actually does. |

| Framing Direction | Framework Range | Question Variant Code | Retirement Age Presented in the Question | Number of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 2nd | 3rd | Women | Men | |||

| Neutral | - | V1 | 65 | 63 | 67 | 118 | 104 |

| Gain | Narrow | V2 | 63 | 65 | 67 | 111 | 98 |

| Gain | Broad | V3 | 61 | 65 | 69 | 116 | 100 |

| Loss | Narrow | V4 | 67 | 65 | 63 | 110 | 107 |

| Loss | Broad | V5 | 69 | 65 | 61 | 114 | 101 |

| Total: | 1079 | ||||||

| Characteristics | Number of Responses | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 1079 | 100 |

| Sex | ||

| – Woman | 569 | 52.7 |

| – Man | 510 | 47.3 |

| Age | ||

| – 40–49 | 159 | 14.7 |

| – 45–49 | 275 | 25.5 |

| – 50–54 | 281 | 26.0 |

| – 55–59 | 242 | 22.4 |

| – 60–64 | 122 | 11.3 |

| Education | ||

| – Basic | 268 | 24.8 |

| – Average | 466 | 43.2 |

| – Higher | 345 | 32.0 |

| Type of job | ||

| – professionally inactive | 110 | 10.2 |

| – intellectual, office, administrative work | 296 | 27.4 |

| – manual labor | 260 | 24.1 |

| – profession requiring contact with people, team management | 218 | 20.2 |

| – highly specialized profession | 88 | 8.2 |

| – pensioner (disability) | 107 | 9.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| – without a partner | 271 | 25.1 |

| – has a partner | 808 | 74.9 |

| Number of children | ||

| – lack | 205 | 19.0 |

| – one | 286 | 26.5 |

| – two | 417 | 38.6 |

| – three or more | 171 | 15.8 |

| Domicile | ||

| – village | 393 | 36.4 |

| – city up to 50,000 inhabitants | 250 | 23.2 |

| – city from 50,001 to 200,000 inhabitants | 219 | 20.3 |

| – city over 200,001 inhabitants | 217 | 20.1 |

| Compared Variants | V1-V2 | V1-V3 | V1-V4 | V1-V5 | V2-V3 | V2-V4 | V2-V5 | V3-V4 | V3-V5 | V4-V5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z statistics | −0.303 | −0.217 | −1.288 | −2.836 | 0.087 | −0.968 | −2.493 | −1.063 | −2.601 | −1.542 |

| p-value | 0.762 | 0.828 | 0.198 | 0.005 | 0.931 | 0.333 | 0.013 | 0.288 | 0.009 | 0.123 |

| Bonferroni-corrected p-value | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.046 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.127 | 1.000 | 0.093 | 1.00 |

| Variable | Model 1P | Model 2P | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (>65 Years) | (>67 Years) | |||||||||

| β | SE β | OR | Sig | 95% CI for OR | Β | SE β | OR | Sig | 95% CI for OR | |

| Framing effect (ref.: V1 (neutral)) | *** | *** | ||||||||

| – V2 (gain, narrow) | −0.04 | 0.20 | 0.96 | 0.64–1.42 | −0.14 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.47–1.60 | ||

| – V3 (gain, broad) | −0.49 | 0.20 | 0.61 | ** | 0.41–0.90 | 1.36 | 0.26 | 3.89 | *** | 2.33–6.48 |

| – V4 (loss, narrow) | 0.37 | 0.21 | 1.45 | * | 0.97–2.16 | −0.27 | 0.32 | 0.76 | 0.41–1.41 | |

| – V5 (loss, broad) | 0.10 | 0.20 | 1.11 | 0.74–1.64 | 1.66 | 0.26 | 5.26 | *** | 3.17–8.69 | |

| Sex (ref.: female) | 0.61 | 0.14 | 1.85 | *** | 1.39–2.44 | 0.81 | 0.18 | 2.25 | *** | 1.57–3.22 |

| Age (continuous variable) | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.96 | *** | 0.93–0.97 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.96 | *** | 0.92–0.98 |

| Education (ref.: primary) | *** | *** | ||||||||

| – secondary | 0.68 | 0.16 | 1.97 | *** | 1.43–2.69 | 0.63 | 0.23 | 1.90 | 1.21–2.97 | |

| – higher | 1.08 | 0.17 | 2.93 | *** | 2.08–4.12 | 1.08 | 0.23 | 2.95 | *** | 1.87–4.64 |

| Marital status (ref.: without a partner) | −0.38 | 0.15 | 0.69 | ** | 0.50–0.92 | Variable not included in the model | ||||

| Constant | 2.01 | 0.59 | 7.48 | *** | −0.82 | 0.74 | 0.44 | |||

| Significance of the model (Omnibus tests of model coefficients p-value) | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| −2 Log likelihood | 1381.54 | 956.43 | ||||||||

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.080 | 0.131 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.107 | 0.204 | ||||||||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p-value) | 0.311 | 0.157 | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jedynak, T. Does the Formulation of the Decision Problem Affect Retirement?—Framing Effect and Planned Retirement Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041977

Jedynak T. Does the Formulation of the Decision Problem Affect Retirement?—Framing Effect and Planned Retirement Age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(4):1977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041977

Chicago/Turabian StyleJedynak, Tomasz. 2022. "Does the Formulation of the Decision Problem Affect Retirement?—Framing Effect and Planned Retirement Age" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 4: 1977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041977

APA StyleJedynak, T. (2022). Does the Formulation of the Decision Problem Affect Retirement?—Framing Effect and Planned Retirement Age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 1977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041977