The Systematic Workplace-Improvement Needs Generation (SWING): Verifying a Worker-Centred Tool for Identifying Necessary Workplace Improvements in a Nursing Home in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Assumptions and Limitations of Previous Studies

1.3. SWING’s Specifications

1.3.1. Procedures and Advantages

1.3.2. SWING’s Expected Contributions to Occupational Health, Theoretical Appropriateness, and Originality

1.4. Purpose and Hypotheses of the Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Recruitment

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Qualitative/Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. SWING Results and Practical Implications

4.2. SWING’s Versatility

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Labour Organization. Report of the Director-General: Decent Work. 1999. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc87/rep-i.htm (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Weiss, D.J.; Dawis, R.V.; England, G.W.; Lofquist, L. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire; Industrial Relations Center, Work Adjustment Project, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E. Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: Development of the Job Satisfaction Survey. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1985, 13, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimet, G.; Dahlem, N.W. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R.; Brisson, C.; Kawakami, N.; Houtman, I.; Bongers, P.; Amick, B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 322–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimomitsu, T.; Haratani, T.; Ohno, Y. The final development of the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire mainly used for assessment of the individuals. In Ministry of Labour Sponsored Grant for the Prevention of Work-Related Illness: The 1999 Report; Kato, M., Ed.; Tokyo Medical College: Tokyo, Japan, 2000; pp. 126–164. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ando, E.; Kawakami, N.; Shimazu, A.; Shimomitsu, T.; Odagiri, Y. Reliability and validity of the English version of the New Brief Job Stress Questionnaire. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Occupational Health, Seoul, Korea, 31 May–5 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Brief Job Stress Questionnaire English Version. 2016. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/roudoukijun/anzeneisei12/dl/stress-check_e.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Kristensen, T.S.; Hannerz, H.; Høgh, A.; Borg, V. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire: A tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2005, 31, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahara, H.; Yamada, T.; Nagafuchi, K.; Shirakawa, C.; Suzuki, K.; Mafune, K.; Kubota, S.; Hiro, H.; Mishima, N.; Nagata, S. Development of a work improvement checklist for occupational mental health focused on requests from workers. J. Occup. Health 2009, 51, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, M.A.; Drasgow, F.; Munson, L.J. The Perceptions of Fair Interpersonal Treatment Scale: Development and validation of a measure of interpersonal treatment in the workplace. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Quality of Worklife Questionnaire. 2010. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/stress/pdfs/QWL2010.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Walkey, F.H.; Green, D.E. An exhaustive examination of the replicable factor structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1992, 52, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikusooka, M.; Elci, O.C.; Özdemir, H. Job satisfaction among Syrian healthcare workers in refugee health centres. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Ren, Z.; Wang, Q.; He, M.; Xiong, W.; Ma, G.; Fan, X.; Guo, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. The relationship between job stress and job burnout: The mediating effects of perceived social support and job satisfaction. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of Engagement and burnout: A confirmative analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, K.N.; Cortina, L.M. Observed Workplace Incivility toward Women, Perceptions of Interpersonal Injustice, and Observer Occupational Well-Being: Differential Effects for Gender of the Observer. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, S.; Govindarajulu, U.; Joseph, M.; Landsbergis, P. Changes in work characteristics over 12 years: Findings from the 2002–2014 US National NIOSH Quality of Work Life Surveys. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, S.; Govindarajulu, U.; Joseph, M.A.; Landsbergis, P. Work Characteristics, Body Mass Index, and Risk of Obesity: The National Quality of Work Life Survey. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2021, 65, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; DeJoy, D.M. Occupational injury in America: An analysis of risk factors using data from the General Social Survey (GSS). J. Saf. Res. 2012, 43, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Yoshikawa, E.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kogi, K.; Jung, M.H. Utility of action checklists as a consensus building tool. Ind. Health 2015, 53, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yoshikawa, E.; Kogi, K. Outcomes for facilitators of workplace environment improvement applying a participatory approach. J. Occup. Health 2019, 61, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the Meaning of Work: A Theoretical Integration and Review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.A. The Psychology of Personal Constructs; Norton: Bronx, NY, USA, 1955; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle, C.A.; McGee, H.M.; Hickey, A.; O’Malley, K.; Joyce, C.R. Individual quality of life in patients undergoing hip replacement. Lancet 1992, 339, 1088–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, S.; Gallo, G.; Valle, A.; Cugno, C.; Chiò, A.; Calvo, A.; Cavalla, P.; Zibetti, M.; Rivoiro, C.; Oliver, D.J. Specialist palliative care improves the quality of life in advanced neurodegenerative disorders: NE-PAL, a pilot randomised controlled study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2017, 7, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linse, K.; Rüger, W.; Joos, M.; Schmitz-Peiffer, H.; Storch, A.; Hermann, A. Usability of eyetracking computer systems and impact on psychological wellbeing in patients with advanced amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2018, 19, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidou, Z.; Baumstarck, K.; Chinot, O.; Barlesi, F.; Salas, S.; Leroy, T.; Auquier, P. Domains of quality of life freely expressed by cancer patients and their caregivers: Contribution of the SEIQoL. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzumura, M.; Fushiki, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Oura, A.; Suzumura, S.; Yamashita, M.; Mori, M. A prospective study of factors associated with risk of turnover among care workers in group homes for elderly individuals with dementia. J. Occup. Health 2013, 55, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holton, J.A. The coding process and its challenges. In The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory; Bryant, A., Charmaz, K., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2007; pp. 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. Labour Force Survey (Employed Person [by Age Group]). 2021. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/roudou/lngindex.html (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Mori, K.; Takebayashi, T. The introduction of an occupational health management system for solving issues in occupational health activities in Japan. Ind. Health 2002, 40, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savicki, V.; Cooley, E. The relationship of work environment and client contact to burnout in mental health professionals. J. Couns. Dev. 1987, 65, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, J.E.; Walter, C.A. Retention plans and job satisfaction of gerontological social workers. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 1992, 19, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenoweth, L.; Low, L.F.; Goodenough, B.; Liu, Z.; Brodaty, H.; Casey, A.N.; Spitzer, P.; Bell, J.P.; Fleming, R. Potential benefits to staff from humor therapy with nursing home residents. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2014, 40, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, S.; Raja, U. Why does workplace bullying affect victims’ job strain? Perceived organization support and emotional dissonance as resource depletion mechanisms. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 4311–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, K.P. Psychological Aspects of Workplace Harassment and Preventive Measures: A Review. Int. J. Manag. 2017, 8, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Becton, J.B.; Gilstrap, J.B.; Forsyth, M. Preventing and correcting workplace harassment: Guidelines for employers. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, T.; Lopes, M.P. Crafting a calling: The mediating role of calling between challenging job demands and turnover intention. J. Career Dev. 2017, 44, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterud, T.; Hem, E.; Lau, B.; Ekeberg, O. A comparison of general and ambulance specific stressors: Predictors of job satisfaction and health problems in a nationwide one-year follow-up study of Norwegian ambulance personnel. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2011, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakuraya, A.; Shimazu, A.; Eguchi, H.; Kamiyama, K.; Hara, Y.; Namba, K.; Kawakami, N. Job crafting, work engagement, and psychological distress among Japanese employees: A cross-sectional study. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2017, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carette, B.; Anseel, F.; Lievens, F. Does career timing of challenging job assignments influence the relationship with in-role job performance? J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Park, K.; Hwang, H. How Managers’ Job Crafting Reduces Turnover Intention: The Mediating Roles of Role Ambiguity and Emotional Exhaustion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas, M.A.; Díaz-Fúnez, P.; Pecino, V.; López-Liria, R.; Padilla, D.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M. Consequences of team job demands: Role ambiguity climate, affective engagement, and extra-role performance. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Sung, M. How symmetrical employee communication leads to employee engagement and positive employee communication behaviors: The mediation of employee-organization relationships. J. Commun. Manag. 2017, 21, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S.P. Patient-reported outcomes: How useful are they? Med. Writ. 2017, 26, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mercieca-Bebber, R.; King, M.T.; Calvert, M.J.; Stockler, M.R.; Friedlander, M. The importance of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials and strategies for future optimization. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2018, 9, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Purpose | Advantage/Disadvantage | Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota Job Satisfaction Questionnaire [2] | To provide more specific information about particular aspects of the job that individuals find rewarding rather than measuring general job satisfaction. | This questionnaire can examine the status of job satisfaction from both the individual (intrinsic) and environmental (extrinsic) perspectives. However, given the diversity of workplaces and occupations, a myriad of additional studies is needed to ensure the generality of the items in this scale. | Twenty aspects of job satisfaction, e.g., ability utilisation, achievement, and activity, are measured using a five-point Likert scale. |

| Job Satisfaction Survey [3] | To measure the job satisfaction of workers, especially those in welfare, public, and non-profit sector organisations. | Based on the theory that job satisfaction is an emotional or attitudinal response to work, this scale is composed of items that can be applied to any occupation. Contrarily, such items do not fully reflect the improvement needs in individual workplaces. | Job satisfaction composed by the nine factors, e.g., pay, promotion, and supervision, are measured using a six-point Likert scale. |

| Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [4] | To provide a brief rating to identify the social support that an individual receives from family, friends, and significant others. | Although this scale can evaluate the level of social support received from others such as friends and family, the relationships with others such as pets or psychotherapists are not examined because such relationships are outside the scope of this scale. | Perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others is measured using a seven-point Likert scale for 12 items. |

| Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey [5] | To measure the status of burnout as workers’ response to job-related stress. | This scale takes the theoretical position that burnout is a crisis that occurs in the relationship between self and work, instead of as a result of interpersonal relationships, and thus can be applied to workers in a variety of industries. However, the appropriateness of the factor structure of this scale is debatable [14]. | Frequencies to the burnout-related questionnaire items consisting of exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy sub-factors are measured using a seven-point Likert scale. |

| Job Content Questionnaire [6] | To measure important workplace problems that are often overlooked because they are difficult to assess in terms of their job content. | This questionnaire is based on a theory that explains occupational stress in terms of an imbalance between job responsibilities and discretionary authority, and the items are comprehensive. Contrarily, when this scale is used for a new population, it is necessary to verify whether such items can measure job content appropriately. | This scale contains of 49 items in five scales: decision latitude, psychological demands and mental workload, social support, physical demands, and job insecurity, and measures subjects’ work environment using four-point Likert scale. |

| Brief Job Stress Questionnaire [7,8,9] | To achieve work improvement for both individuals and workplaces through the prevention of mental health problems among workers. | Although the questionnaire includes items on all aspects of physical, mental, and social health, it does not measure the subjective importance/weight of each item or factor. | Questions regarding job stressors, psychological stress reactions, and social supports are asked using a four-point Likert scale. |

| Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire [10] | To improve and facilitate research and practical interventions at workplaces by assessing psychosocial factors at work, stress, employees’ well-being, and some personality factors. | This scale can examine both internal factors, e.g., personality, and environmental factors, e.g., time for tasks, by measuring psychosocial factors related to work in three dimensions: workplace, work-individual interface, and individual. However, the subjective importance of each question item is not included in the scope of this scale. | This scale measures an individual’s internal and environmental factors. Although the method of measurement varies depending on the question, most of the responses are measured using a five-point Likert scale. |

| Mental Health Improvement & Reinforcement Research of Recognition [11] | To obtain information from objective assessments of mental health among workers to understand the state of the workplace and to make improvements. | Because this questionnaire consists of questions about working conditions and environment, it is easy for researchers to gain an objective understanding of workplace conditions, thus leading to improvement. Contrarily, subjective assessment of the importance or relevance of questionnaire items assigned by individual workers on is not possible. | Using a four-point Likert scale, the degree of need for improvement in items related to mental health in a workplace, e.g., workload and supervisor behaviour, is evaluated. |

| Perceptions of Fair Interpersonal Treatment scale [12] | To assess employees’ perceptions of interpersonal treatment in their workplace, that is, their sense of fairness. | This scale can extract harassment and oppression in interpersonal relationships. Contrarily, this scale assumes a two-party relationship between the worker and the supervisor or co-worker; thus, it is not able to examine the content and quality of the work itself. | This scale is composed of supervisor and co-worker factors, and the degree of applicability to the items is asked and scored using a three-point Likert scale. |

| Quality of Worklife Questionnaire [13] | To examine the quality of work life by examining a wide range of organisational issues. | This questionnaire examines a wide range of factors related to worker safety and health such as job level, working hours, and culture. However, the extent to which workplace-improvement needs are subjectively met is not explored in this questionnaire. | For each of the nine aspects of work-life, e.g., job level, culture/climate, and health outcomes, subjects choose the ones that apply and rate them on a Likert scale or describe them. |

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 18 (34) |

| Female | 35 (66) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 46 ± 13.5 |

| <30 | 6 (11.3) |

| 30–39 | 12 (22.6) |

| 40–49 | 18 (34.0) |

| 50–59 | 7 (13.2) |

| ≥60 | 10 (18.9) |

| SWING Index Score (mean ± SD) | 51.5 ± 21.2 |

| Job stress; median (25–75 percentile) | 2.275 (2.21–2.42) |

| Variables | SWING Index Score | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.370 | |

| Male | 47.8 | |

| Female | 53.4 | |

| Age group | 0.001 * | |

| <30 a | 73.9 | |

| 30–39 b | 53.7 | |

| 40–49 c | 54 | |

| 50–59 d | 50.6 | |

| ≥60 e | 31.4 | |

| Job stress | 0.3 | 0.029 * |

| Work-Improvement Needs Items | Example |

|---|---|

| Balance of workload | Appropriate work volume and workload; The number of customer appropriate to the situation at the workplace. |

| Benefit package | Welfare; Good support for childcare; Enjoyment beside work such as company trip. |

| Communication with colleagues | Good communication in the workplace; Reflection of opinions from each worker regardless of workplace hierarchy; No backbiting, swearing, or whispering. |

| Commuting conditions | Commuting distance and hours; Presence of convenience store nearby; Location of workplace; Distance from home to workplace. |

| Desire for recognition | Mutual respect among workers; Feeling that I am needed by the company. |

| Flexibility of work | Security of private time; Work-life balance; No unreasonable working hours; Less overtime work; Controllability of work and rest; |

| Holidays | Ease of taking vacations; Ease of taking paid holidays; Many holidays in year end and new-year, and summer/winter vacations. |

| Human relations | Good human relations; Harmony; Cheerful atmosphere; Stress-free relations in workplace; Polite manner such as greetings. |

| Information sharing | Ease of opinion exchange; Each staff member understands his or her own position and role, and performs his or her work; Sharing new information, knowledge, and methods for work. |

| Interaction with customers | Positive feedback from customers; Smiling faces of customers motivate me. |

| Legal compliance and rules at work | Legally appropriate working hours; Uniformed and clear work flow; Strict adherence to food hygiene. |

| Number of staff | Sufficient number of staff; Appropriate Employment management. |

| Personnel evaluation | Fairness; Transparency of the evaluation system; Presence of evaluation criteria based on effort, innovation, productivity in individuals, instead of attendance number of work. |

| Physical/psychological harassment | An environment free of moral harassment; No bullying; Equal treatment without pressure or imposition. |

| Possibility of self-growth | Good education program; Environment where skills and knowledge can be improved; Well-developed human resource development system. |

| Relationship of trust in the workplace | Trust among staff members; No sense of distrust; No selfish attitude; Helping each other; Working together in case of trouble. |

| Rewarding and challenging work | Job that I like, am good at, and want to do; Job satisfaction; Motivating and rewarding; Rewarding or a sense of accomplishment in work. |

| Salary | Satisfactory salary and wage levels; Properly paid salary; Wages commensurate with the nature of the work; Compensation for the overtime hours. |

| Sharing of goals and objectives | Shared values in the company; Agreeable management policy of the facility; Common goals; Leader who can put him/herself in our position. |

| Trusted person to confide in | Ease of consultation about both work and non-work matters to colleague and/or supervisor; Respectable and reliable supervisor; Accurate advice that corrects mistakes and leads to success. |

| Work environment | Cleanliness of workplace; Well-equipped facilities; Maintenance; Air conditioning; Necessary supplies well-stocked. |

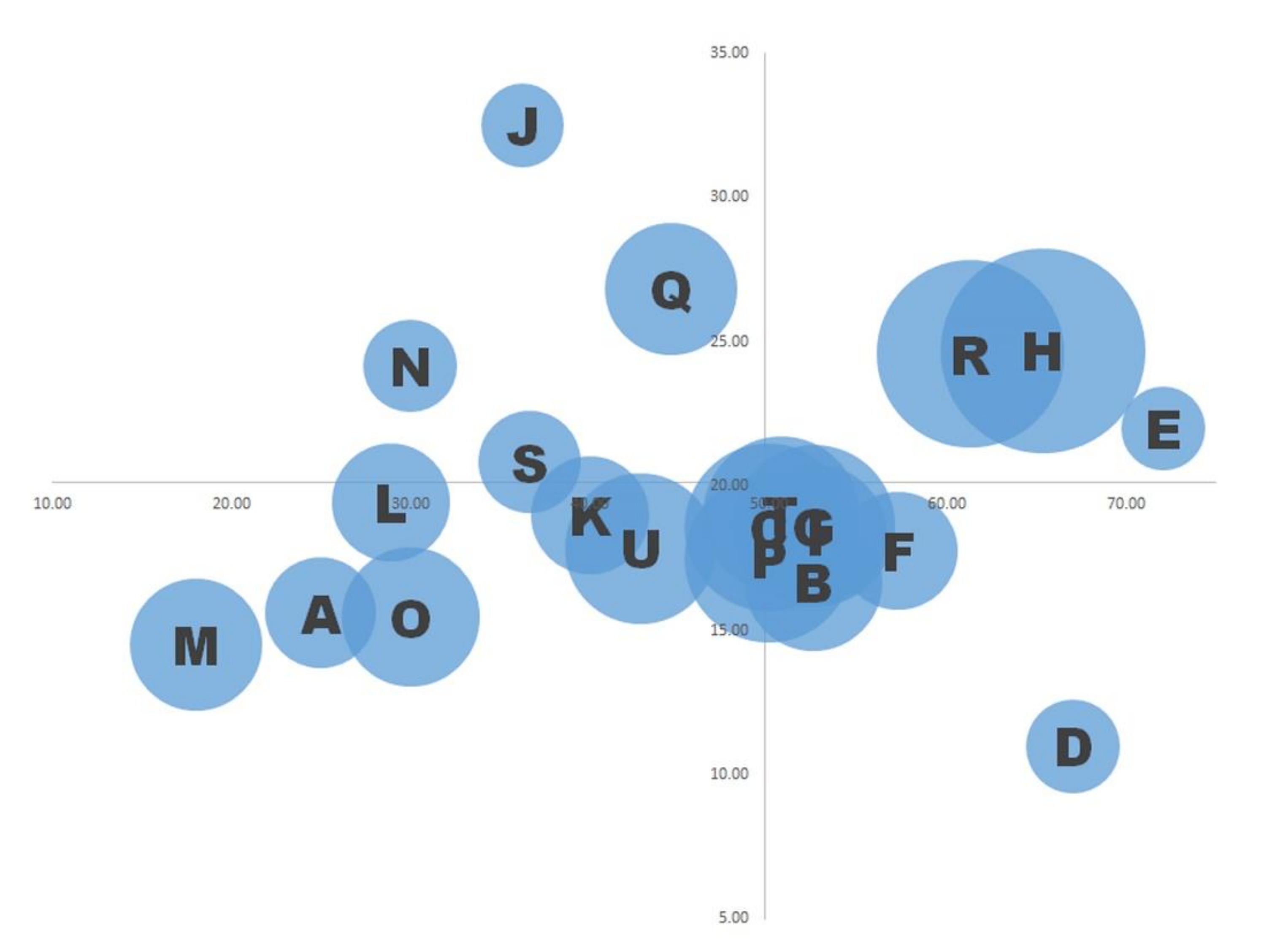

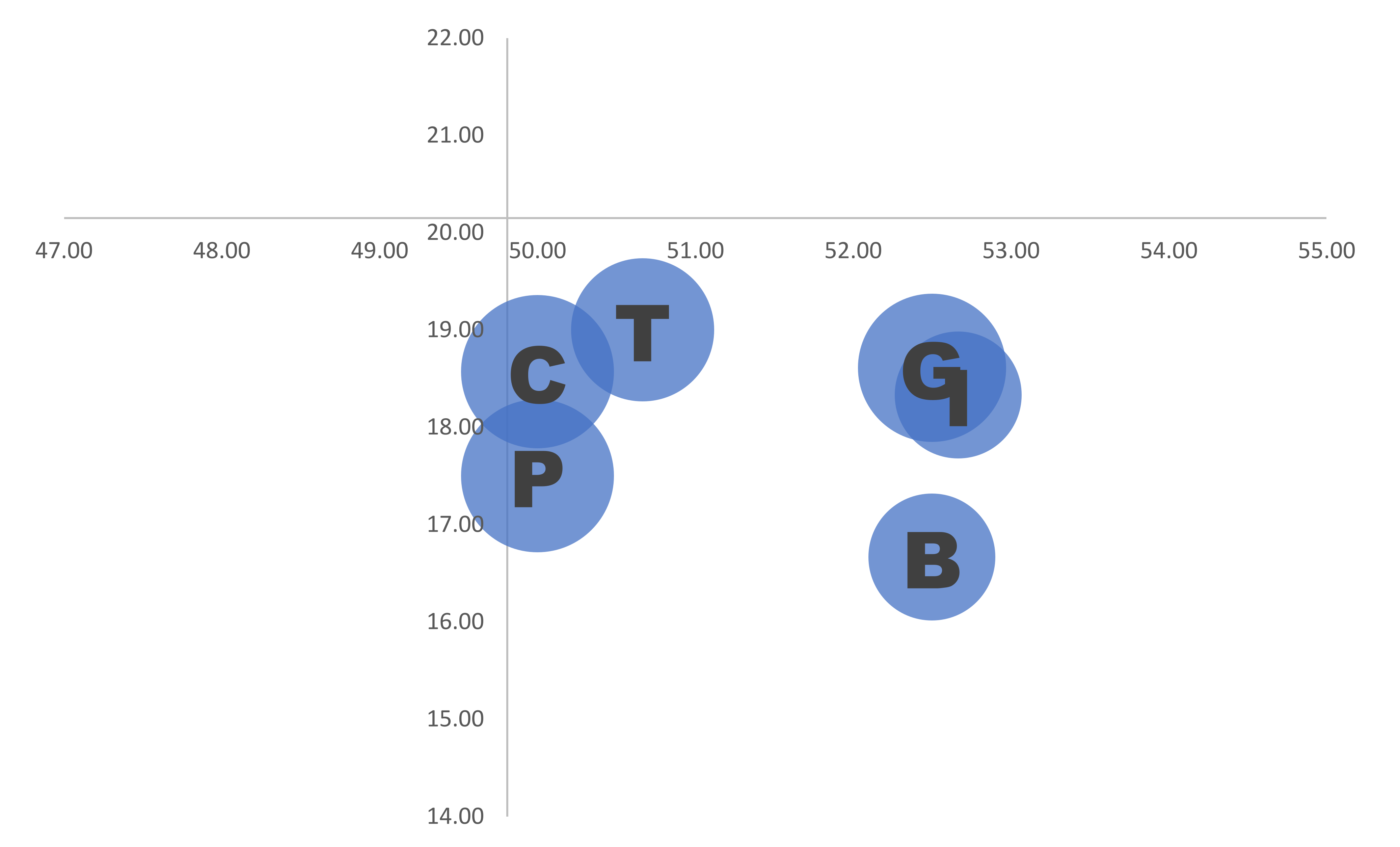

| Item | Sufficiency Level | Weight Balance | Total Number of Individuals Who Mentioned (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall mean ± SD | 49.8 ± 26.4 | 20.2 ± 10.7 | |

| Balance of workload | 25.00 | 15.63 | 7 (13.2) |

| Benefit package | 52.50 | 16.67 | 11 (20.8) |

| Communication with colleagues | 50.00 | 18.57 | 16 (30.2) |

| Commuting conditions | 67.00 | 11.00 | 5 (9.4) |

| Desire for recognition | 72.00 | 22.00 | 4 (7.5) |

| Flexibility of work | 57.22 | 17.78 | 8 (15.1) |

| Holidays | 52.50 | 18.61 | 15 (28.3) |

| Human relations | 65.29 | 24.71 | 24 (45.3) |

| Information sharing | 52.67 | 18.33 | 11 (20.8) |

| Interaction with customers | 36.25 | 32.50 | 4 (7.5) |

| Legal compliance and rules at work | 40.00 | 19.00 | 8 (15.1) |

| Number of staff | 28.89 | 19.44 | 8 (15.1) |

| Personnel evaluation | 18.00 | 14.50 | 10 (18.9) |

| Physical/psychological harassment | 30.00 | 24.17 | 5 (9.4) |

| Possibility of self-growth | 30.00 | 15.45 | 11 (20.8) |

| Relationship of trust in the workplace | 50.00 | 17.50 | 16 (30.2) |

| Rewarding and challenging work | 44.55 | 26.82 | 10 (18.9) |

| Salary | 61.25 | 24.58 | 20 (37.7) |

| Sharing of goals and objectives | 36.67 | 20.83 | 6 (11.3) |

| Trusted person to confide in | 50.67 | 19.00 | 14 (26.4) |

| Work environment | 42.86 | 17.86 | 13 (24.5) |

| Cases and Items | Sufficiency Level | Weight Balance | Score (Index Score) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | |||

| Benefit package | 60 | 20 | 12 |

| Human relations | 50 | 10 | 5 |

| Interaction with customers | 0 | 40 | 0 |

| Possibility of self-growth | 30 | 10 | 3 |

| Work environment | 30 | 20 | 6 |

| Index Score | 26 | ||

| Case 2 | |||

| Flexibility of work | 70 | 20 | 14 |

| Personnel evaluation | 90 | 20 | 18 |

| Possibility of self-growth | 50 | 20 | 10 |

| Relationship of trust in the workplace | 20 | 20 | 4 |

| Rewarding and challenging work | 20 | 20 | 4 |

| Index Score | 50 | ||

| Case 3 | |||

| Communication with colleagues | 90 | 10 | 9 |

| Commuting conditions | 95 | 10 | 9.5 |

| Desire for recognition | 90 | 30 | 9.5 |

| Holidays | 95 | 10 | 27 |

| Work environment | 90 | 20 | 18 |

| Index Score | 73 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hidaka, T.; Sato, S.; Endo, S.; Kasuga, H.; Masuishi, Y.; Kakamu, T.; Fukushima, T. The Systematic Workplace-Improvement Needs Generation (SWING): Verifying a Worker-Centred Tool for Identifying Necessary Workplace Improvements in a Nursing Home in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031671

Hidaka T, Sato S, Endo S, Kasuga H, Masuishi Y, Kakamu T, Fukushima T. The Systematic Workplace-Improvement Needs Generation (SWING): Verifying a Worker-Centred Tool for Identifying Necessary Workplace Improvements in a Nursing Home in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031671

Chicago/Turabian StyleHidaka, Tomoo, Sei Sato, Shota Endo, Hideaki Kasuga, Yusuke Masuishi, Takeyasu Kakamu, and Tetsuhito Fukushima. 2022. "The Systematic Workplace-Improvement Needs Generation (SWING): Verifying a Worker-Centred Tool for Identifying Necessary Workplace Improvements in a Nursing Home in Japan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031671

APA StyleHidaka, T., Sato, S., Endo, S., Kasuga, H., Masuishi, Y., Kakamu, T., & Fukushima, T. (2022). The Systematic Workplace-Improvement Needs Generation (SWING): Verifying a Worker-Centred Tool for Identifying Necessary Workplace Improvements in a Nursing Home in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031671