Social Skills Group Training for Students with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities in Senior High School—A Qualitative Multi-Perspective Study of Social Validity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Settings

2.2. Design and Procedure

2.3. Interventions

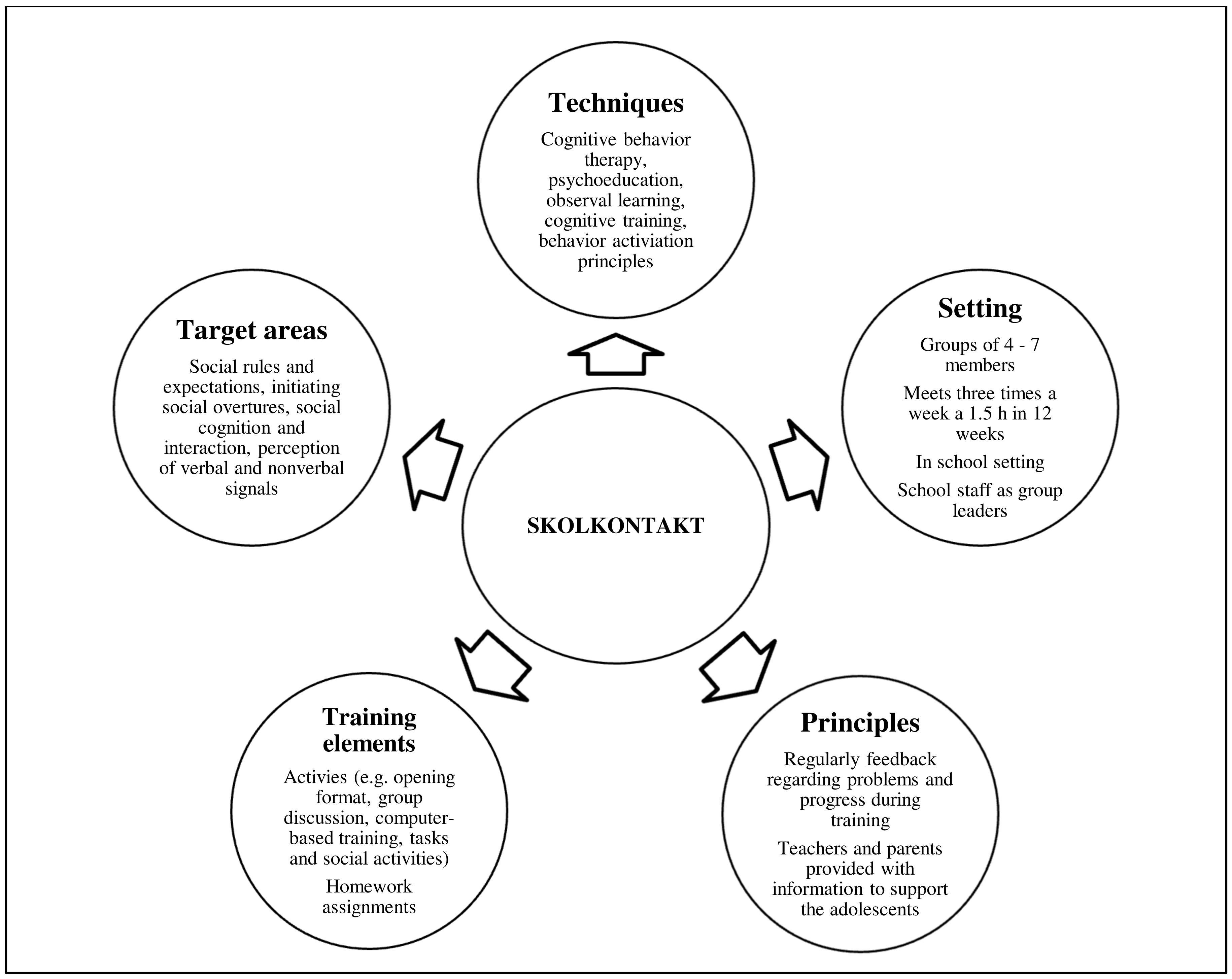

2.3.1. Social Skills Group Training

2.3.2. Social Activity Control Group

2.4. Interviews

2.5. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

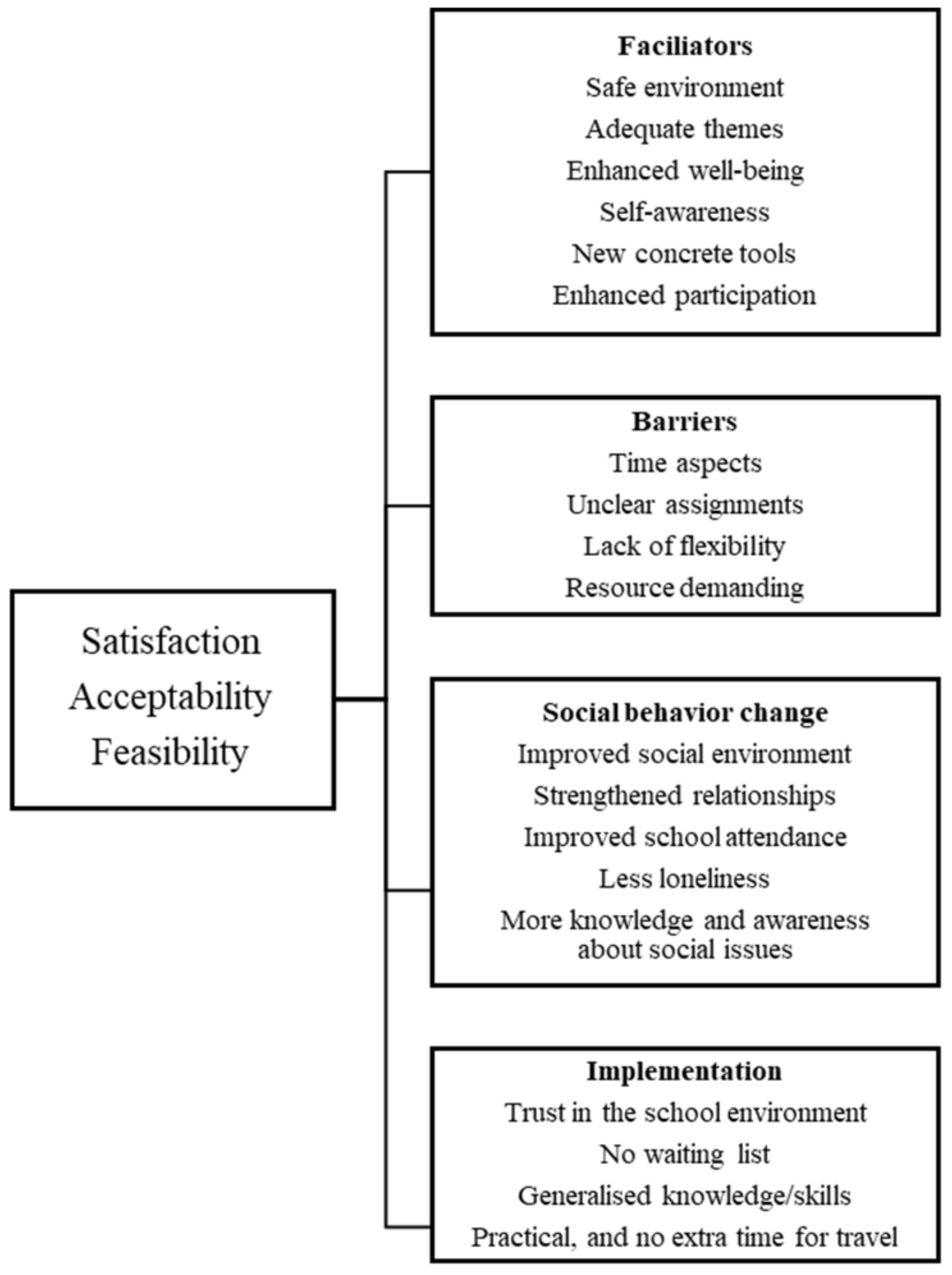

3.1. Social Validity of SSGT—Thematic Structure

3.2. Facilitators

3.2.1. SKOLKONTAKT

“The best part was probably the discussions. I have difficulties with talking to peers and express my opinion. I learned how to talk about different things and how to express my own attitudes. It is good to have this on a regular basis, to ventilate and try to be open.”(Adolescent 1)

“The discussions were good; they were about things youths worry and think a lot about. When you talk about it in a group and discuss thoughts and actions, then you don’t feel that lonely, and life doesn’t feel that hard. You are not alone with your thoughts. The themes were good.”(Adolescent 2)

“I felt safe in the group. The group size was good, and I liked the regular training.”

“My goals were to answer questions and to be able to talk in class and during oral presentations. I have practiced on things I feel uncomfortable with, so it has been of value for me.”(Adolescent 9)

“Ahh, it will be valuable to me in the future, if I go to university. It is good to have practiced raising your voice.”(Adolescent 10)

“You notice which students you can stretch; you learn that they’re actually not that fragile and that they like when you challenge them.”(Teacher 1)

“We got motivated when we saw the development in the adolescents. When we saw things happen in school it helped us to see the benefits of programs like this. Even if it takes time and is a little bit inflexible, it is worth it when you watch the adolescents’ interactions.”(Teacher 2)

“Ahh, we have a lot of knowledge already, but after this we have more insight in processes and things that are difficult for the adolescents, as well as how they think, and I think we use this new awareness unconsciously.”(Teacher 1)

“Some of the adolescents have been bullied before, and I hope they can remember this training and the good feelings and enhanced self-confidence, and that it will make them try out the skills in new social settings.”(Teacher 4)

“You improve the general social climate in school when the adolescents with most social impairments gain new skills, if you do that, you see changes in the individual as well as in the big group.”(Teacher 2)

“It is valuable because we have learnt new ways of working with improving the social environment and we have never before had such a friendly open group of social science students.”(School leader 2)

“Most of our students have social difficulties and the school can become very quiet and without interactions, so we want to continue with the training and want other schools to do the same.”(School leader 1)

“It feels like a relief in some way, it feels like several knots have been dissolved, and that we had students like isolated islands and even with destructive relationships. Now it is friendlier, they know how to talk to each other.”(School leader 1)

“The knowledge is spread within the school since we learn from each other, even if not all teachers were part of the training. We gain the same understanding.”(School leader 1)

3.2.2. Social Activity Control

“If I have learnt something valuable? I don’t really know. Maybe that I now can make cupcakes counts, now I can bake that, but I don’t really know.”(Adolescent 5)

“Best parts? Ahh, we liked the physical activities, but outdoor activities were sometimes horrible with rain and bad weather, we tried, we know physical activities are good and especially important for this targeting group, they are inactive.”(Teacher 3)

“We are more comfortable now in providing social activities for the students, but with the education we will probably add new tools to our knowledge.”(Teacher 5)

3.3. Barriers

SKOLKONTAKT

“All things were challenging and hard for me, yes, but I try to have a positive view and it’s good to practice the things you can’t do, you will be a better person, I had to fight.”(Adolescent 10)

“Sometimes I did not have that much time to work towards my goals.”(Adolescent 10)

“Ahh, when we all have the same social difficulties, interactions can be challenging and hard, when we need to talk to each other.”(Adolescent 12)

“I mean it is no quick fix. We have conducted 36 sessions. Change takes time.”(Teacher 1)

“In the beginning I was shocked by all the theories, theory of mind and all the text, I thought the adolescents would quit. More flexibility would be good, now we followed the manual strictly.”(Teacher 2)

“The weekly assignments were a little bit difficult sometimes. It was confusing in the beginning how to do them, but the feedback from the researchers was good.”(Teacher 4)

“The concrete weekly assignments were the best, when the adolescents did things like going to the bank or ordering something at a café. We could not change the activities since we followed the manual.”(Teacher 3)

“Three times a week is a lot, it is time and cost demanding. And, ahh all the paperwork, it takes time to read and learn the content of the program, but with more flexibility in the program, and if school psychologist can be involved, it is possible.”(Teacher 4)

“The program could be shorter, but that is difficult too, it’s part of the thing, that it takes time. With less time it would have been stressful and not that good for the participating students.”(Teacher 4)

“It takes time and has to be included into the schedule, but it is valuable and we believe we can use it in the future in more flexible forms. The teachers need deep knowledge. The manual might be good for more inexperienced teachers to use at the start.”(School leader 1)

“When organizing, there are several things to consider, it is expensive in the form of resources and our teachers that facilitate SSGT have fewer teaching hours. In the beginning, the teachers had a lot of content to learn, they were not familiar with the manuals, the feedback and possibilities to ask the researchers was valuable.”(School leader 1)

“We had a worried parent initially, she said her child couldn’t do some things, but the safe environment at school and the presence of other adolescents with the same difficulties helped and the parent was relieved.”(School leader 2)

3.4. Social Behavior Change

3.4.1. SKOLKONTAKT

“The training has contributed to, ahh, it has helped me to follow a rhythm and keep me on the right path when it comes to thinking processes and behavior patterns. It has helped me to create new habits and it is very nice to do it in a group, not alone. I like that the training was at school.”(Adolescent 3)

“Now I have contact with some peers, we can talk about what´s important, and I can get support from them without worrying about what other think. I feel very lonely and to experience that others have the same issues helps.”(Adolescent 2)

“I actually had some friends coming over to my birthday party for the first time. I used to watch people with friends thinking it would never happen to me.”(Adolescent 6)

“If this was valuable for me? I would say yes, definitely, ahh, we have more contact. That I now have contact with others and can talk about what’s important.”(Adolescent 1)

“For me, participation was a game changer—it saved me.”(Adolescent 6)

“The students are more relaxed and you see them talk to each other and laugh. Some of them were wallflowers, if you don’t give them opportunities to practice they will remain silent.”(Teacher 2)

“Positive effects? I saw this great development in a student that I have followed, it is a huge difference. Before, she did not want to sit next to peers or talk to anybody. She has other body language now and takes initiatives. Now I see that she has friends and is happier and more relaxed.”(Teacher 4)

“The adolescents now have networks of friends from the groups. We see big changes among some of the adolescents. The group has helped them to build trust and they talk much more with each other.”(Teacher 3)

“The social goals have helped them and I think it affects the academic achievement too. You have adolescents with no motor and the new feeling with sense of context and enhanced participation, ahh and safety affect results in school.”(Teacher 4)

“The students are more open and take initiatives to social activities. They have by themselves suggested social groups like gardening group or movie clubs. We did not see this earlier. They interact across age groups as well. It is pretty fantastic and would not happen last year. It spreads like rings on water, it benefits everyone.”(School leader 1)

“We cannot believe in some of the adolescents’ development and change. It is a big difference and this participant has different body language and seems so much happier.”

“These students are sometimes often absent from school and it is important to work preventatively and that they gain self-awareness and can practice what challenges them.”(School leader 2)

3.4.2. Social Activity Control

“Concrete change? No, I don’t think so. I think of the Yoga session, and that my body is really stiff.”(Adolescent 5)

“If it has helped me? Well, perhaps the games helped me socially. When I see other people, I am more social compared to when I play games on the Internet. I suppose it is good to practice on it.”(Adolescent 7)

3.5. Implementation

Skolkontakt

“The advantages with social skills training in school compared to outside school is that it is very accessible, you don’t have to hassle with remiss to a place with long waiting list and such, and if you have issues with getting friends in your school, you get the grounds and have actually talked to people at school in your group and you can talk to them again.”(Adolescent 4)

“I have conducted social skills training before, but it is very easy in school, you don’t have to take all the responsibility since the training is in school with a set time during the week.”(Adolescent 2)

“The training in school is good, you feel safe, in child psychiatry you don’t know anyone, in school you might know someone in the group, ahh and it’s more familiar.”(Adolescent 10)

“We need to see these adolescents and exactly because many of them have difficulties with interaction and communication, we need this. It is important for the future, the social part is very, very important, and we want them to succeed after school.”(Teacher 5)

“This is realistic in the school environment, and it is a question of democracy and policy, if you could measure the long-term effects of the training you see the benefits for society. It is what results we measure, whether the academic achievement and marks are ok is one side, but then, what next, do we want the adolescents to just stay home and stare at the walls, what’s next for them?”(Teacher 1)

“We have integrated the training in the ordinary curriculum, it is tough and an expensive intervention, it could work with professionals from outside, however it is best with staff from the school, we know the students.”(Teacher 2)

“Our students might not have difficulties with school and achievement, the social environment is their big issue. You can use the networks from the groups and interactions are more smooth and natural.”(Teacher 1)

“Students with NDDs as well as other students with social impairments or anxiety need to learn strategies, and they are at all schools. We have seen a need of practicing social skills. We have often solved conflicts afterwards. It is not always in the schedule and curriculum and we see this as a complement. It has been a driving force.”(School leader 1)

“We had been looking for how to develop and strengthen the school and looked for something that was evidence-based and could work. The activities conducted in the control group are social activities we have done before.”(School leader 1)

“It is important that the researchers understand the school environment, everything has to be transparence from the beginning. It is a big project and researchers have to understand what is reasonable to request.”(School leader 2)

3.6. Real-Life Training vs. Digital SSGT or Social Control Activities

“For me it worked digitally, but it is better to meet for real. It was a little bit like you did not see each other for real. It would have been better to meet physically, but there is not much you can do about it.”(Adolescent 9)

“It was quite ok, clearly it would have been more fun to meet in person. I have not immediately made any friends after joining, it is harder to get in touch maybe when it’s online. Some things can be done but others not. The physical activities were hard to conduct.”(Adolescent 11)

“Oh, first of all, it was boring not to meet face to face, you missed the social part, but otherwise I think it has worked surprisingly well. It was not that fun, but you have to make the best out of it.”(Adolescent 10)

“When transformed to digital, the physical activities were more difficult, however we tried digital walks and communicating online with the adolescents. We could talk to them, but you are more sensitive when you meet them.”(Teacher 4)

“We saw some changes after the digital training, some things like relief and that the students could somehow breathe more freely and that it was easier to be in the same room.”(Teacher 5)

“The digital format works for some and doesn’t for others, for some it is shit. You see the development in some, while others make less progress.”(Teacher 5)

“For students with big social stress and anxiety, who stay home from school, it can be very urgent here, and it can be easier to start online.”(Teacher 5)

“Ahh, in other words it was much easier the last time when we had physical meetings, when you saw the group, you saw progress in just a couple of weeks, I believe it is important to be seen.”(Teacher 4)

“I see differences from now when it’s digital compared to IRL. We could see more concrete change after last session with physical meetings. We saw that the students actually talked to each other and you as a teacher could talk to them informal more freely at lunch and recess, which had not been possible before. Now when the training was digital, we see more individual progress than interactions. We see that the students have more knowledge and understanding, but I don’t believe in enhanced interaction effects when the training is online.”(Teacher 2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5th); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thapar, A.; Cooper, M.; Rutter, M. Neurodevelopmental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bölte, S.; Mahdi, S.; Coghill, D.; Gau, S.S.-F.; Granlund, M.; Holtmann, M.; Karande, S.; Levy, F.; Rohde, L.A.; Segerer, W.; et al. Standardised assessment of functioning in ADHD: Consensus on the ICF Core Sets for ADHD. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 1261–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bölte, S.; Mahdi, S.; De Vries, P.J.; Granlund, M.; Robison, J.E.; Shulman, C.; Swedo, S.; Tonge, B.; Wong, V.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; et al. The Gestalt of functioning in autism spectrum disorder: Results of the international conference to develop final consensus International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health core sets. Autism 2018, 23, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zablotsky, B.; Black, L.I.; Maenner, M.J.; Schieve, L.A.; Danielson, M.L.; Bitsko, R.H.; Blumberg, S.J.; Kogan, M.D.; Boyle, C.A. Prevalence and Trends of Developmental Disabilities among Children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalsgaard, S.; Østergaard, S.D.; Leckman, J.F.; Mortensen, P.B.; Pedersen, M.G. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A nationwide cohort study. Lancet 2015, 385, 2190–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvikoski, T.; Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Boman, M.; Larsson, H.; Lichtenstein, P.; Bölte, S. Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mcconaughy, S.H.; Volpe, R.J.; Antshel, K.M.; Gordon, M.; Eiraldi, R.B. Academic and Social Impairments of Elementary School Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 40, 200–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Taylor, J.; Duncan, A.; Bishop, S. Peer Victimization and Educational Outcomes in Mainstreamed Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 3557–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.; O’Reilly, M.; Ledbetter-Cho, K.; Lang, R.; Sigafoos, J.; Kuhn, M.; Lim, N.; Gevarter, C.; Caldwell, N. A Meta-analysis of School-Based Social Interaction Interventions for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 4, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Simpson, K.; Keen, D. School-related anxiety symptomatology in a community sample of primary-school-aged children on the autism spectrum. J. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 70, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, S.; Anaby, D.; Bergthorson, M.; Majnemer, A.; Elsabbagh, M.; Zwaigenbaum, L. Participation of Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Scoping Review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 2, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, S.; Coleyshaw, L. Participation or exclusion? Perspectives of pupils with autistic spectrum disorders on their participation in leisure activities. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2010, 39, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.; Fitton, C.; Steiner, M.F.C.; McLay, J.S.; Clark, D.; King, A.; Mackay, D.F.; Pell, J.P. Educational and Health Outcomes of Children Treated for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, e170691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Korrel, H.; Mueller, K.L.; Silk, T.; Anderson, V.; Sciberras, E. Research Review: Language problems in children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder—A systematic meta-analytic review. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauminger, N.; Shulman, C. The Development and Maintenance of Friendship in High-Functioning Children with Autism. Autism 2003, 7, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spithoven, A.W.M.; Lodder, G.M.A.; Goossens, L.; Bijttebier, P.; Bastin, M.; Verhagen, M.; Sholte, R.H.J. Adolecents’ loneliness and depression associated with friendship experiences and well-being: A person-centered approach. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.; Jaafar, J.; Bilyk, N.; Ariff, M.R.M. Social Skills, Friendship and Happiness: A Cross-Cultural Investigation. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 152, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford-Smith, M.; Brownell, C. Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance, friendships, and peer networks. J. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 41, 235–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, M.C.; Colpin, H.; Van Leeuwen, K.; Bijttebier, P.; Noortgate, W.V.D.; Claes, S.; Goossens, L.; Verschueren, K. School engagement trajectories in adolescence: The role of peer likeability and popularity. J. Sch. Psychol. 2017, 64, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Morris, A.S. Adolescent development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, J.N.; Todd, R.D. Autistic traits in the general population: A twin study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bölte, S.; Lawson, W.B.; Marschik, P.B.; Girdler, S. Reconciling the seemingly irreconcilable: The WHO’s ICF system integrates biological and psychosocial environmental determinants of autism and ADHD: The international Classification of Functioning (ICF) allows to model opposed biomedical and neurodiverse views of autism and ADHD within one framework. BioEssays 2021, 43, e2000254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- UNESCO & Ministry of Education and Science Spain. The Salamanca Statement Framework for Action on Special Needs Education, Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality, Salamanca, Spain. UNESCO. 1994. Available online: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/salamanca-statementandframework.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- UNESCO; Peppler Barry, U. The Dakar Framework for Action: Education for All: Meeting Our Collective Commitments including Six Regional Frameworks for Action, Adopted by the World Education Forum, Dakar, Senegal. UNESCO, Paris. 2000. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000121147 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- UNESCO. Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All. 2005. Available online: http://www.ibe.unesco.org/sites/default/files/Guidelines_for_Inclusion_UNESCO_2006.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). 2006. Available online: https://www.un.or/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Artiles, A.J.; Kozleski, E.B.; Dorn, S.; Christensen, C. Chapter 3: Learning in Inclusive Education Research: Re-mediating Theory and Methods with a Transformative Agenda. Rev. Res. Educ. 2006, 30, 65–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.; Roach, V.; Frey, N. Examining the general programmatic benefits of inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2002, 6, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Charman, T.; Havdahl, A.; Carbone, P.; Anagnostou, E.; Boyd, B.; Carr, T.; de Vries, P.J.; Dissanayake, C.; Divan, G.; et al. The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. Lancet 2021, 399, 271–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, I.; Woodcock, S. Inclusive education policies: Discourses of difference, diversity and deficit. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2014, 19, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Inclusive Education. Including Children with Disabilities in Quality Learning: What Needs to Be Done? 2017. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/IE_summary_accessible_220917_brief.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Pellicano, L.; Bölte, S.; Stahmer, A. The current illusion of educational inclusion. Autism 2018, 22, 386–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bölte, S.; Leifler, E.; Berggren, S.; Borg, A. Inclusive practice for students with neurodevelopmental disorders in Sweden. Scand. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Psychol. 2021, 9, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, B.; Kasari, C.; Rotheram-Fuller, E. Involvement or Isolation? The Social Networks of Children with Autism in Regular Classrooms. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 37, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotheram-Fuller, E.; Kasari, C.; Chamberlain, B.; Locke, J. Social involvement of children with autism spectrum disorders in elementary school classrooms. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.R.; Evans, S.W.; Baran, A.; Khondker, F.; Press, K.; Noel, D.; Wasserman, S.; Belmonte, C.; Mohlmann, M. Comparison of accommodations and interventions for youth with ADHD: A randomized controlled trial. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 80, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leifler, E.; Carpelan, G.; Zakrevska, A.; Bölte, S.; Jonsson, U. Does the learning environment ‘make the grade’? A systematic review of accommodations for children on the autism spectrum in mainstream school. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 28, 582–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovett, B.J.; Nelson, J.M. Systematic Review: Educational Accommodations for Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 60, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.A.; Russell, A.; Matthews, J.; Ford, T.J.; Rogers, M.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Kneale, D.; Thompson-Coon, J.; Sutcliffe, K.; Nunns, M.; et al. School-based interventions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review with multiple synthesis methods. Rev. Educ. 2018, 6, 209–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, B.M.; Webster, A.A.; Westerveld, M.F. A systematic review of school-based interventions targeting social communication behaviors for students with autism. Autism 2018, 23, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, J.A.; Kang, E.; Lerner, M.D. Efficacy of group social skills interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 52, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolstencroft, J.; Robinson, L.; Srinivasan, R.; Kerry, E.; Mandy, W.; Skuse, D. A Systematic Review of Group Social Skills Interventions, and Meta-analysis of Outcomes, for Children with High Functioning ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 2293–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choque Olsson, N.; Flygare Coco, C.; Görling, A.; Råde, A.; Chen, Q.; Bölte, S. Social skills training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freitag, C.M.; Jensen, K.; Elsuni, L.; Sachse, M.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Schulte-Rüther, M.; Cholemkery, H. Group-based cognitive behavioural psychotherapy for children and adolescents with ASD: The randomized, multicenter, controlled SOSTA-net trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2016, 57, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storebø, O.J.; Andersen, M.E.; Skoog, M.; Hansen, S.J.; Simonsen, E.; Pedersen, N.; Tendal, B.; Callesen, H.E.; Faltinsen, E.; Gluud, C. Social skills training for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD008223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, D.; Siceloff, E.R.; Morse, M.; Neger, E.; Flory, K. Stand-Alone Social Skills Training for Youth with ADHD: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentzel, K.R. Peer relationships, motivation and academic performance at school. In Handbook of Competence and Motivation; Elliot, A.J., Dweck, C.S., Yeager, D.S., Eds.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul, G.J.; Weyandt, L.L. School-based intervention for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Effects on academic, social and behavioural functioning. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2006, 53, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, N.C.; Rautio, D.; Asztalos, J.; Stoetzer, U.; Bölte, S. Social skills group training in high-functioning autism: A qualitative responder study. Autism 2016, 20, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mikami, A.Y.; Smit, S.; Khalis, A. Social skills and ADHD—What works? Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koegel, R.; Fredeen, R.; Kim, S.; Danial, J.; Rubinstein, D.; Koegel, L. Using Perseverative Interests to Improve Interactions Between Adolescents with Autism and Their Typical Peers in School Settings. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2012, 14, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verduyn, C.; Lord, W.; Forrest, G. Social skills training in schools: An evaluation study. J. Adolesc. 1990, 13, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moote, G.T.; Smyth, N.J.; Wodarski, J.S. Social Skills Training With Youth in School Settings: A Review. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 1999, 9, 427–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Pachan, M. A Meta-Analysis of after-School Programs That Seek to Promote Personal and Social Skills in Children and Adolescents. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 45, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Taylor, R.D.; Schellinger, K.B. The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugeson, E.A.; Sanderson, J.; Tucci, L.; Bates, S. The ABC’s of teaching social skills to adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: The UCLA PEERS program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2244–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, J.; Wolk, C.B.; Harker, C.; Olsen, A.; Shingledecker, T.; Barg, F.; Mandell, D.; Beidas, R. Pebbles, rocks, and boulders: The implementation of a school-based social engagement intervention for children with autism. Autism 2016, 21, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, M.; Chang, Y.-C. A systematic review of school-based social skills interventions and observed social outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder in inclusive settings. Autism 2021, 25, 1828–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.; Sheen, J.; Ling, M.; Foley, D.; Sciberras, E. Interventions for Adolescents With ADHD to Improve Peer Social Functioning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Atten. Disord. 2020, 25, 1479–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, Y.; Miyazaki, C.; Mikami, M.; Ota, E.; Mori, R.; Hwang, Y.; Terasaka, A.; Kobayashi, E.; Kamio, Y. Meta-analyses of individual versus group interventions for pre-school children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196272. [Google Scholar]

- Myhr, G.; Payne, K. Cost-Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Mental Disorders: Implications for Public Health Care Funding Policy in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2006, 51, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thucker, M.; Oei, T. Is group more cost effective than individual cognitive behaviour therapy? The evidence is not solid yet. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2007, 35, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, T.A.; Machalicek, W. Systematic review of intervention research with adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2013, 7, 1439–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Långh, U.; Hammar, M.; Klintwall, L.; Bölte, S. Allegiance and knowledge levels of professionals working with early intensive behavioural intervention in autism. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2016, 11, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, U.; Olsson, N.C.; Bölte, S. Can findings from randomized controlled trials of social skills training in autism spectrum disorder be generalized? The neglected dimension of external validity. Autism 2015, 20, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottema-Beutel, K.; Mullins, T.S.; Harvey, M.N.; Gustafson, J.R.; Carter, E.W. Avoiding the “brick wall of awkward”: Perspectives of youth with autism spectrum disorder on social-focused intervention practices. Autism 2015, 20, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellicano, E.; Dinsmore, A.; Charman, T. What should autism research focus upon? Community views and priorities from the United Kingdom. Autism 2014, 18, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stockholm County Council. Stockholms Läns Landsting. Regionalt Vårdprogram ADHD, Lindrig Utvecklingsstörning och Autismspektrumtillstånd hos Barn, Ungdomar och Vuxna. [Regional Service Program-ADHD, Intellectual Disabilities and Autism Spectrum Disorders in Children, Adolescents and Adults]; Stockholm Läns Landsting: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bölte, S.; Fridell, A.; Borg, A.; Coco, C. Gruppträning i Skolan för Elever Med Sociala och Kommunikativa Svårigheter. (SKOLKONTAKT®) [Group Training in School for Students with Autism and Other Documented Social Challenges]; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bölte, S. Social Färdighetsträning i Grupp Med Fokus på Kommunikation och Social Interaktion vid Autismspektrumtillstånd Enligt Frankfurtmodellen (KONTAKT). [Social Skills Group Training for Autistic Individuals Focusing on Communication and Social Interactions according to the Frankfurt Model (KONTAKT)]; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tammimies, K.; Li, D.; Rabkina, I.; Stamouli, S.; Becker, M.; Nicolaou, V.; Berggren, S.; Coco, C.; Falkmer, T.; Jonsson, U.; et al. Association between Copy Number Variation and Response to Social Skills Training in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, D.; Choque-Olsson, N.; Jiao, H.; Norgren, N.; Jonsson, U.; Bölte, S.; Tammimies, K. The influence of common polygenic risk and gene sets on social skills group training response in autism spectrum disorder. NPJ Genom. Med. 2020, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, U.; Olsson, N.C.; Coco, C.; Görling, A.; Flygare, O.; Råde, A.; Chen, Q.; Berggren, S.; Tammimies, K.; Bölte, S. Long-term social skills group training for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 28, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolf, M.M. Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart1. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1978, 11, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Making Human Beings Human, Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kasari, C.; Rotheram-Fuller, E.; Locke, J.; Gulsrud, A. Making the connection: Randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 53, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leifler, E. Teachers’ capacity to create inclusive learning environments. Int. J. Lesson Learn. Stud. 2020, 9, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottiani, J.H.; Duran, C.A.; Pas, E.T.; Bradshaw, C.P. Teacher stress and burnout in urban middle schools: Associations with job demands, resources, and effective classroom practices. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 77, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parson, S.; Mitchell, P.; Leonard, A. Do adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders adhere to social conventions in virtual environments? Autism 2005, 9, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stichter, J.P.; Laffey, J.; Galyen, K.; Herzog, M. iSocial: Delivering the Social Competence Intervention for Adolescents (SCI-A) in a 3D Virtual Learning Environment for Youth with High Functioning Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 44, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.K.; Johnson, C.; Sukhodolsky, D.G. The role of the school psychologist in the inclusive education of school-age children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Sch. Psychol. 2005, 43, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koegel, R.; Kim, S.; Koegel, L.K. Training Paraprofessionals to Improve Socialization in Students with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2197–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyk, S.; Reutebuch, C.K.; Carter, E.W.; Hedges, S.; El Zein, F.; Fan, H.; Gustafson, J.R. Addressing the needs of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Considerations and complexities for high school interventions. Except. Child. 2015, 81, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, A.Y.; Lerner, M.D.; Lun, J. Social Context Influences on Children’s Rejection by Their Peers. Child Dev. Perspect. 2010, 4, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, U.; Coco, C.; Fridell, A.; Brown, S.; Berggren, S.; Hirvikoski, T.; Bölte, S. Proof of concept: The TRANSITION program for young adults with autism spectrum disorder and/or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 28, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Mazidi, S.H.; Al-Ayadhi, L.Y. National Profile of Caregivers’ Perspectives on Autism Spectrum Disorder Screening and Care in Primary Health Care: The Need for Autism Medical Home. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoza, B.; Gerdes, A.C.; Mrug, S.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Bukowski, W.M.; Gold, J.A.; Arnold, L.E.; Abikoff, H.B.; Conners, C.K.; Elliott, G.R.; et al. Peer-Assessed Outcomes in the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2005, 34, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Gender | Age | Primary Clinical Diagnosis | Co-Existing Diagnosis/Symptoms | Intervention Group | Interview Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 20 | ADHD | Social anxiety | SKOLKONTAKT | School |

| Female | 19 | ASD | - | SKOLKONTAKT | School |

| Diverse | 18 | ADHD | ASD, dyslexia | SKOLKONTAKT | School |

| Male | 18 | ADHD | ASD | SKOLKONTAKT | School |

| Male | 20 | ADHD | ASD | SKOLKONTAKT | Digitally from school |

| Female | 18 | ASD | ADD, OCD, Social anxiety | SKOLKONTAKT | Phonecall |

| Female | 18 | ADHD | ASD | Activity group | School |

| Male | 17 | ASD | Activity group | School | |

| Diverse | 17 | ASD | Activity group | School | |

| Male | 17 | ADHD | ASD | Activity group | Digitally from school |

| Diverse | 17 | ASD | ADHD | Activity group | Digitally from school |

| Male | 17 | ASD | Anxiety | Activity group | Digitally from school |

| Female | 19 | Social anxiety | Subclinical autistic symptoms | Activity group | Digitally from home |

| Training Format | Description | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Mandatory | ||

| Agenda | Detailed and visualized information of the session, the structure and activities. | Give a clear structure and create safety through routines and transparency. |

| Opening session | Round of introductions. Expressions of feelings (visual support in emotion-figures as scaffolding structures). How do people feel today? Do they have something to share? Are there wishes for today’s session? | Warm-up activity, initiate contact, build safety, start interactions and give the opportunity to express mood, feelings and motivation. |

| Closing session | Evaluation of the session and recap of the day. Sharing positive and negative experiences with the activities and tasks. Round of evaluations. | Promotion of interaction between group members. Practicing talking in a group and remembering names and endorsing social overtures. |

| Recurring | ||

| Snack-time | Interaction in a non-structured situation. | Practice small-talk, practice turn-taking and encourage social skills use. |

| Group rules | Rules are formulated and founded by the group. Rules are visualized and made concrete for adolescents. Examples of rules: listen actively to each other, secrecy, only give positive feedback and use kind language. | Building safety and trust in the group and treating each other with respect. Creating an environment where adolescents dare to talk, open up and share experiences. |

| Homework assignments | Setting and perusing meaningful individual and general social communication goals. Examples of individual goals: ask questions, handle stressful situations, understand nonverbal signs and make an appointment with a classmate. | Building and training skills outside of the training context, behavior activation and generalization of skills to everyday situations. Personalization of social skills training. |

| Coaching sessions towards assignments and individual goals | Assignments are followed up and feedback is given by experienced facilitators. Barriers to goal attainment are analyzed and elements for goal completion are established. Group trainers give constructive feedback towards the assignments. | Reinforcement of social successful behaviors or receive suggestions on alternative approaches to goal attainment. Fine-tuning of personal goals. Opportunity to talk about own social experiences regarding concrete actions. |

| Variable | ||

| Group activities | Baking together, cooking, playing sports and visiting a café or a museum. | Group cohesion and practicing cooperation and social skills in an informal setting. |

| Group discussions | Discussion of specific topics, e.g., to have social contact, recognize social situations in school, have feelings of loneliness, issues and typical problems of being young and to handle changes, misunderstandings and conflicts in school and life. | Exchanging experiences, social cognition, social relationships, feeling safe in a social setting, daring to raise your voice and have an opinion, sharing advice, practicing active listening and learning ways to handle challenges, stress and emotions. |

| Group exercises | Group games, social interaction games, how to handle stressful activities, watching the Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition and facial affect recognition training. | Developing strategies for difficult social situations. Practice and discuss real-life situations, improve social thinking and detect socially relevant nonverbal signs. |

| Role-play | Participants play and practice challenges and real-life scenarios, where the group members discuss the situations and actions of the protagonists to find solutions and an action plan. | Mimicking and solving different social scenarios in a safe environment so that they are able to handle social situations better in real life and school. |

| Students | Teachers | School Leaders |

|---|---|---|

| Which elements and contents from the training */activities ** do you recall? | Generally, what do you recall from the training/activities? | How did you receive information about the training/activities and the research project? |

| Which parts of the training/activities did you like the most, and why? | Which parts of the training/activities did you like the most/the least, and why? | Do you think there is a need of the training/activities in school settings? |

| Which part of the training/activities did you like the least, and why? | Are training/activities like this appropriate as part of your work at school? | Is the training/are the activities appropriate for your school setting? |

| Is there anything in the training/activities that you would have liked to train/do more or less? *** | Is there anything about the training/activities that you would have liked to focus on/do more or less? *** | In your role as school leader, what did you need to consider and had to arrange to implement the training/activities at your school? |

| What did you think of the group discussions? *** | What did you think of the group discussions? Were the themes in the discussion appropriate and valuable? *** | In which way have the training/activities positively and negatively influenced daily life at your school? |

| What did you think of the training homework? *** | What did you think of the training homework? * | Can you see any changes among the adolescents or the teachers associated with training/activities? |

| Do you think some parts of the training/activities might have helped you? Which activities and why? | Do you think some parts of the training/activities might have helped the adolescents? Which activities and why? | Is it realistic and possible to implement training/activities at your school in the future? |

| Do you think the training/activities have improved your social skills? In what way? | Have you seen any enhanced interactions or improved social behaviors in the adolescents following training/activities? | What is important to consider for implementation of training/activities? What training, resources and support do your staff need for implementation? |

| Are there any concrete or specific changes, positive or negative, in your life that you think are due to the training/activities? | Are there any concrete or specific changes, positive or negative, that you have observed or noticed, that you think are due to the training/activities? | Are there any areas of possible improvements from your view according to the whole process and co-operation with researchers? |

| Do you think participating in the training/the activities will give you long-lasting improved social skills in life or in school? If so, in what way? | What do you think of long-lasting effects after the training/activities? Are there any? Have you seen any? | Which parts of the training/activities do you think are valuable or less valuable for your school? |

| Is there anything that could be better or made differently in the training/activities? | Is it possible and realistic to conduct training/activities like these in school in the future? | Do you think the training/activities have any spin-off effects for the adolescents in school and outside? |

| Were there enough, too many or too few training/activities sessions? | What do you think of the amount of the training/activities’ sessions? | Do you think the number of sessions of the training/activities were appropriate? |

| What do you think of the fact that this training is in your school? Is it positive or negative? Have you taken part of training/activities like this before somewhere else? Did the training/activities put an additional burden on you? | Do you think you have gained more knowledge and tools to help and understand your students, to develop the adolescents’ understanding of others, to develop the acceptance of the adolescents among others, to motivate and teach the adolescents to strengthen social interaction, to modify your teaching in order to help students to reach their goals and help the students to develop self-esteem? | Do you think your teachers have gained more knowledge and tools during training/activities to help the students to develop skills and reach social goals and other achievements? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leifler, E.; Coco, C.; Fridell, A.; Borg, A.; Bölte, S. Social Skills Group Training for Students with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities in Senior High School—A Qualitative Multi-Perspective Study of Social Validity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031487

Leifler E, Coco C, Fridell A, Borg A, Bölte S. Social Skills Group Training for Students with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities in Senior High School—A Qualitative Multi-Perspective Study of Social Validity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031487

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeifler, Emma, Christina Coco, Anna Fridell, Anna Borg, and Sven Bölte. 2022. "Social Skills Group Training for Students with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities in Senior High School—A Qualitative Multi-Perspective Study of Social Validity" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031487

APA StyleLeifler, E., Coco, C., Fridell, A., Borg, A., & Bölte, S. (2022). Social Skills Group Training for Students with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities in Senior High School—A Qualitative Multi-Perspective Study of Social Validity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031487