Dietary Habits, Diet Quality, Nutrition Knowledge, and Associations with Physical Activity in Polish Prisoners: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Assessment of the Level of Physical Activity

2.3. Dietary Habits, Diet Quality and Nutrition Knowledge Level

- the “Pro-Healthy Diet Index”: pHDI-10 of 0–6.66—low; 6.67–13.33—moderate; 13.34–20—high;

- the “Non-Healthy Diet Index”: nHDI-14 of 0–9.33—low; 9.34–18.66—moderate; 18.67–28—high.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dietary Habits, Diet Quality and Nutrition Knowledge Level

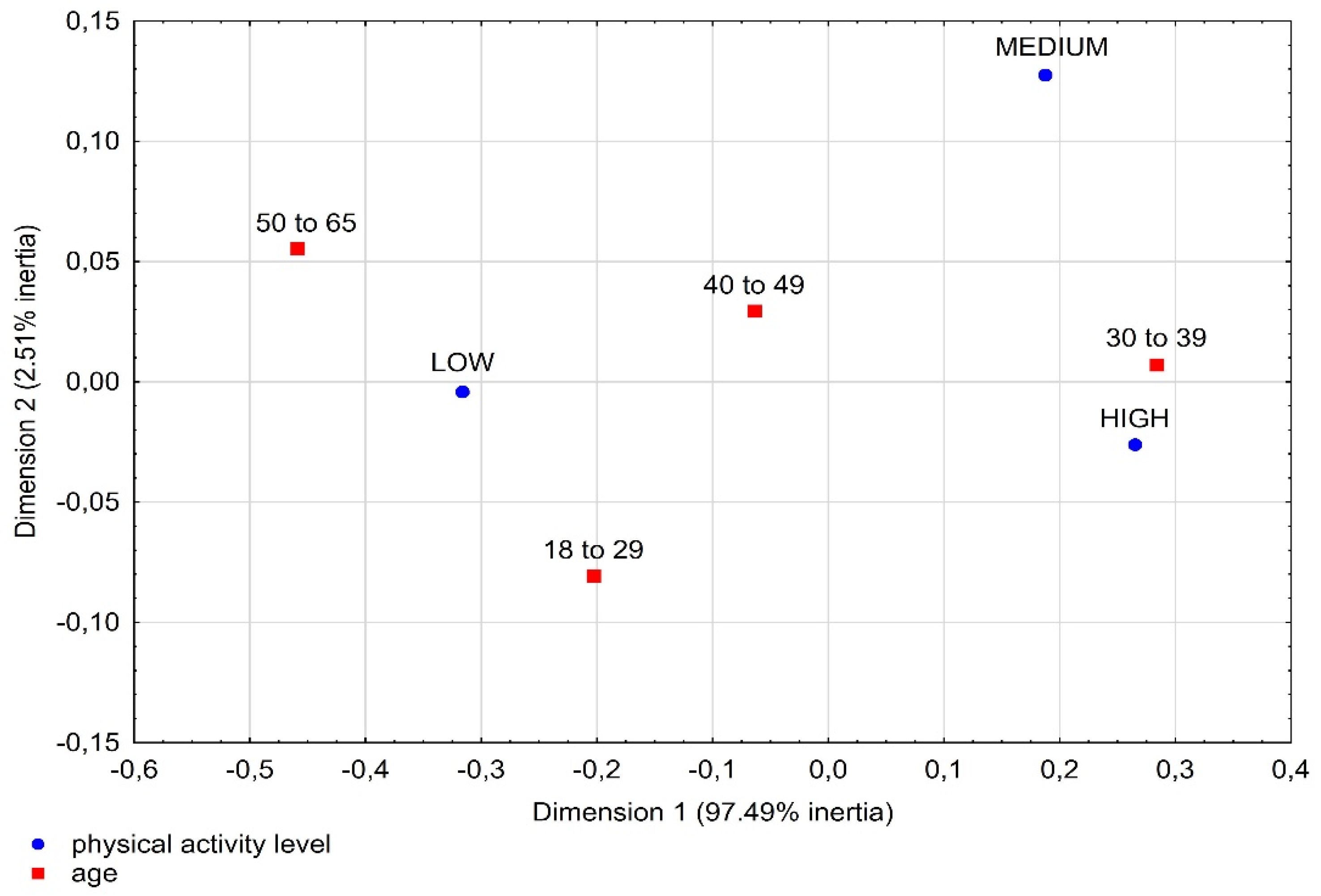

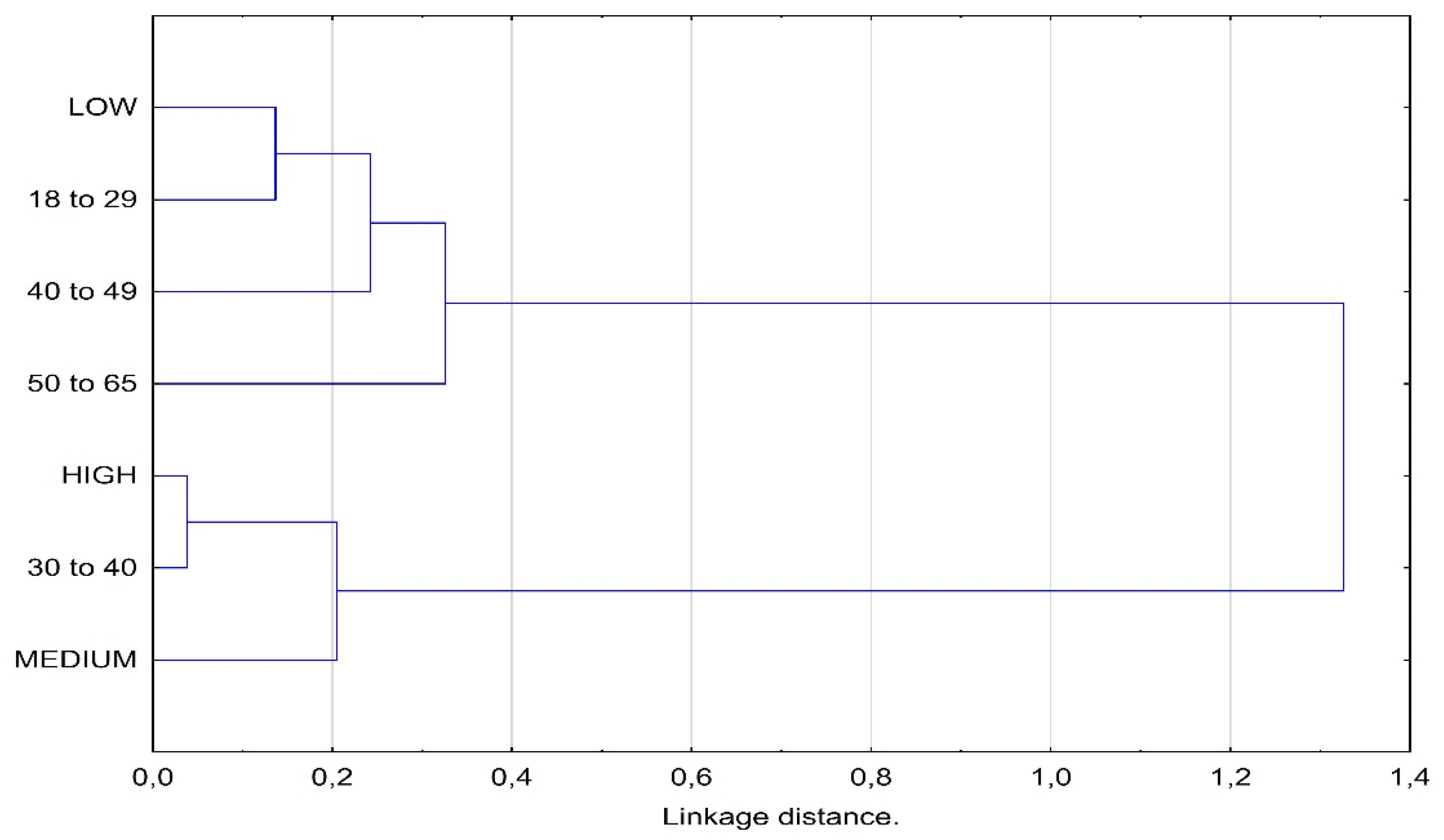

3.2. Associations of Dietary Habits, Food Consumption Frequency, and Nutrition Knowledge with the Level of Physical Activity

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ustawa z Dnia 6 Czerwca 1997 r.—Kodeks Karny Wykonawczy [Act of 6 June 1997—Executive Penal Code]. Dz. U. 1997 Nr 90 poz. 557. Available online: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU19970900557 (accessed on 2 September 2021). (In Polish)

- Kucharska, E.; Seidler, T.; Balejko, E.; Bogacka, A.; Gryza, M.; Szczuko, M. Porównanie całodziennych jadłospisów osadzonych w niektórych aresztach śledczych i zakładach karnych [Comparison of daily dietary rations in some court detention houses and prisons]. Bromatol. Chem. Toksyk. 2009, 42, 36–44. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kosendiak, A.; Trzeciak, D. Motywy i czynniki warunkujące poziom aktywności fizycznej aresztowanych oraz skazanych w warunkach izolacji [Motives and factors conditioning the level of physical activity arrested and convicted people in isolation conditions]. Roz. Nauk. AWF Wroc. 2019, 64, 70–80. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Voller, F.; Silvestri, C.; Martino, G.; Fanti, E.; Bazzerla, G.; Ferrari, F.; Grignani, M.; Libianchi, S.; Pagano, A.M.; Scarpa, F.; et al. Health conditions of inmates in Italy. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, K.; Armstrong, D.; Dregan, A. Systematic review into obesity and weight gain within male prisons. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 12, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, M.K.; Nianogo, R.A.; Arah, O.A. Weight gain during incarceration; Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagarolas-Soler, M.; Alonso-Gaitón, P.; Sapera-Miquel, N.; Valiente-Soler, J.; Sánchez-Roig, M.; Coll-Cámara, A. Diagnosed diabetes and optimal disease control of prisoners in Catalonia. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2020, 22, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harzke, A.J.; Baillargeon, J.G.; Pruitt, S.L.; Pulvino, J.S.; Paar, D.P.; Kelley, M.F. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among inmates in the Texas prison system. J. Urban Health 2010, 87, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeni Njonnou, S.R.; Boombhi, J.; Etoa Etoga, M.C.; Tiodoung Timnou, A.; Jingi, A.M.; Nkem Efon, K.; Mbono Samba Eloumba, E.A.; Ntsama Essomba, M.J.; Kengni Kebiwo, O.; Tsitsol Meke, A.N.; et al. Prevalence of diabetes and associated risk factors among a group of prisoners in the Yaoundé central prison. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 5016327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalbary, M.; Kakani, E.; Ahmed, Y.; Shea, M.; Neyra, J.A.; El-Husseini, A. Characteristics and outcomes of prisoners hospitalized due to COVID-19 disease. Clin. Nephrol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Baillargeon, J. The health of prisoners. Lancet 2011, 377, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan-Jones, M.; Capra, S. What do prisoners eat? Nutrient intakes and food pratcises in a high-secure prison. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanikowski, P.; Michalak-Majewska, M.; Domagała, D.; Jabłońska-Ryś, E.; Sławińska, A. Implementation of dietary reference intake standards in prison menus in Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curd, P.R.; Winter, S.J.; Connell, A. Participative planning to enhance inmate wellness: Preliminary report of a correctional wellness program. J. Correct. Health Care 2007, 13, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curd, P.; Ohlmann, K.; Bush, H. Effectiveness of a voluntary nutrition education workshop in a state prison. J. Correct. Health Care 2013, 19, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E. Television and nutrition in juvenile detention centers. Calif. J. Health Promot. 2005, 3, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.E.; Adamson, S.; Korchinski, M.; Granger-Brown, A.; Ramsden, V.R.; Buxton, J.A.; Espinoza-Magana, N.; Pollock, S.L.; Smith, M.J.F.; Macaulay, A.C.; et al. Incarcerated women develop a nutrition and fitness program: Participatory research. Int. J. Prison. Health 2013, 9, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poklęk, R. Aktywność Fizyczna a Nasilenie Syndromu Agresji Osób Pozbawionych Wolności [Physical Activity and the Level of Aggression Syndrome among Imprisoned People]; Central Board of Prison Service in Poland: Kalisz, Poland, 2008; pp. 41–44. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Poklek-Robert/publication/281204544_Aktywnosc_fizyczna_a_nasilenie_syndromu_agresji_osob_pozbawionych_wolnosci/links/55db086408aec156b9aea69a/Aktywnosc-fizyczna-a-nasilenie-syndromu-agresji-osob-pozbawionych-wolnosci.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021). (In Polish)

- Mohan, A.R.; Thomson, P.; Leslie, S.J.; Dimova, E.; Haw, S.; McKay, J.A. A systematic review of interventions to improve health factors or behaviors of the cardiovascular health of prisoners during incarceration. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 33, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciosek, M.; Pastwa-Wojciechowska, B. Psychologia Penitencjarna [Correctional Psychology]; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 266–269. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Lagarrigue, A.; Ajana, S.; Capuron, L.; Féart, C.; Moisan, M.-P. Obesity in French inmates: Gender differences and relationship with mood, eating behavior and physical activity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Diasparra, M.; Richard, C.; Dubois, L. Influence of physical activity, screen time and sleep on inmates body weight during incarceration in Canadian federal penitentiaries: A retrospective cohort study. Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, E.; Stupnicki, R.; Gajewski, A.K. Międzynarodowy Kwestionariusz Aktywności Fizycznej (IPAQ)—Wersja polska [International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)—Polish version]. Wych. Fiz. I Sport 2007, 51, 47–54. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- IPAQ. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Kowalkowska, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Czarnocinska, J.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Galinski, G.; Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Bronkowska, M.; Dlugosz, A.; Loboda, D.; Wyka, J. Reproducibility of a questionnaire for dietary habits, lifestyle and nutrition knowledge assessment (KomPAN) in Polish adolescents and adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannocci, A.; Mipatrini, D.; D’Egidio, V.; Rizzo, J.; Meggiolaro, S.; Firenze, A.; Boccia, G.; Santangelo, O.E.; Villari, P.; La Torre, G.; et al. Health related quality of life and physical activity in prison: A multicenter observational study in Italy. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, A. Aktywność fizyczna w zakładach karnych a podstawowe wymiary osobowości mężczyzn odbywających karę pozbawienia wolności [Physical activity in prisons and the basic dimensions of personality of men serving prison sentences]. Pol. J. Soc. Rehabil. 2015, 9, 137–157. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J.; Butt, C.; Dawes, H.; Foster, C.; Neale, J.; Plugge, E.; Wheeler, C.; Wright, N. Fitness levels and physical activity among class A drug users entering prison. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 1142–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, C.; Bratina, M.P.; Antonio, M.E. Inmates’ self-reported physical and mental health problems: A comparison by sex and age. J. Correct. Health Care 2020, 26, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.; Rabiee, F.; Weilandt, C. Health promotion and young prisoners: A European perspective. Int. J. Prison. Health 2013, 9, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Blanchard, A.; Dubois, L. Weight gain and mental health in the Canadian prison population. J. Correct. Health Care 2021, 27, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobalska-Kwapis, M.; Suchanecka, A.; Słomka, M.; Siewierska-Górska, A.; Kępka, E.; Strapagiel, D. Genetic association of FTO/IRX region with obesity and overweight in the Polish population. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, K.; Armstrong, D.; Dregan, A. Obesity and weight change in two United Kingdom male prisons. J. Correct. Health Care 2019, 25, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, N.; Clarke, J.G.; Roberts, M.B. Weight change during incarceration: Ground work for a collaborative health intervention. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, D. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in an Italian Prison and relation with average term of detention: A pilot study. Ann. Ig. 2018, 30, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leddy, M.A.; Schulkin, J.; Power, M.L. Consequences of high incarceration rate and high obesity prevalence on the prison system. J. Correct. Health Care 2009, 15, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amtmann, J.; Berryman, D.; Fisher, R. Weight lifting in prisons: A survey and recommendations. J. Correct. Health Care 2003, 10, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devís-Devís, J.; Peirró-Veler, C.; Martos-García, D. Sport and Physical Activity in European Prisons: A Perspective from Sport Personnel. Available online: https://derodeantraciet.be/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Annex_2_-_Sport_and_physical_activity_in_european_prisons_UVEG.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Collins, S.A.; Thompson, S.H. What are we feeding our inmates? J. Correct. Health Care 2012, 18, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.A.; Lee, Y.M.; White, B.D.; Gropper, S.S. The diet of inmates: An analysis of a 28-day cycle menu used in a large county jail in the state of Georgia. J. Correct. Health Care 2015, 21, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.S.A.; Hartwell, H.J.; Reeve, W.G.; Schafheitle, J. The diet of prisoners in England. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanovic, T.; Gosev, M. Is food more than a means of survival? An overview of the Balkan prison systems. Appetite 2019, 143, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eves, A.; Gesch, B. Food provision and the nutritional implications of food choices made by young adult males, in a young offenders’ institution. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2003, 16, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugelvik, T. The hidden food: Mealtime resistance and identity work in a Norwegian prison. Punishm. Soc. 2011, 13, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanikowski, P.; Gustaw, W.; Domagała, D.; Kosendiak, A. Foodservice Systems in Correctional Facilities in Poland; University of Life Sciences: Lublin, Poland, 2021; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Park, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.A.; Park, E.-C. Association between energy drink consumption, depression and suicide ideation in Korean adolescents. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mash, H.B.H.; Fullerton, C.S.; Ramsawh, H.J.; Ng, T.H.; Wang, L.; Kessler, R.C.; Stein, M.B.; Ursano, R.J. Risk for suicidal behaviors associated with alcohol and energy drink use in the US Army. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide a Resource for Prison Officers; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/66725/WHO_MNH_MBD_00.5.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Nowak, D.; Jasionowski, A. Analysis of the consumption of caffeinated energy drinks among Polish adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 7910–7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallucci, A.R.; Martin, R.J.; Morgan, G.B. The consumption of energy drinks among a sample of college students and college student athletes. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasztelański, R. Odlot Zza Krat. Available online: https://tygodnik.tvp.pl/10892285/odlot-zza-krat (accessed on 28 September 2021). (In Polish).

- Elger, B.S. Prison life: Television, sports, work, stress and insomnia in a remand prison. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2009, 32, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, S.; O’Connor, H.; Michael, S.; Gifford, J.; Naughton, G. Nutrition knowledge in athletes: A systematic review. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2011, 21, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popławska, H.; Dmitruk, A.; Kunicka, I.; Dębowska, A.; Hołub, W. Nutritional habits and knowledge about food and nutrition among physical education students depending on their level of higher education and physical activity. Pol. J. Sport Tourism 2018, 25, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniek-Walenda, J.; Brończyk-Puzoń, A.; Jagielski, P. Evaluation of nutrition knowledge using the komPAN questionnaire in acute coronary syndrome patients hospitalized in an invasive cardiology unit. A preliminary report. Folia Cardiologica 2020, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnik-Łucka, M.; Pasieka, P.; Łączak, P.; Rząsa-Duran, E.; Gil, K. Polish pharmacists—Their eating habits and quality of life. Farm. Pol. 2020, 76, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godderis, R. Dining in: The symbolic power of food in prison. Howard J. Crim. Justice 2006, 45, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, J.; Czerniak, U.; Wieliński, D.; Ciekot-Sołtysiak, M.; Zieliński, J.; Gronek, P.; Demuth, A. Pro-healthy diet properties and its determinants among aging masters athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LPAL (n = 93) | MPAL (n = 22) | HPAL (n = 96) | Total (n = 211) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (No. and %) | 0.008 | ||||

| 18–29 | 25 (11.85%) | 3 (1.42%) | 18 (8.53%) | 46 (21.80%) | |

| 30–39 | 29 (13.74%) | 12 (5.69%) | 54 (25.59%) | 95 (45.02%) | |

| 40–49 | 17 (8.06%) | 4 (1.90%) | 16 (7.58%) | 37 (17.54%) | |

| 50–65 | 22 (10.43%) | 3 (1.42%) | 8 (3.79%) | 33 (15.64%) | |

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 38.37 ± 11.99 | 38.00 ± 9.63 | 35.65 ± 7.76 | 37.10 ± 10.07 | N.A. |

| Years of detention (Mean ± SD) | 5.97 ± 6.87 | 6.11 ± 7.94 | 4.66 ± 5.83 | 5.38 ± 6.53 | 0.208 |

| Education (No. and %) | 0.096 | ||||

| Primary | 34 (16.11%) | 3 (1.42%) | 30 (14.22%) | 67 (31.75%) | |

| Lower secondary | 25 (11.85%) | 8 (3.79%) | 23 (10.90%) | 56 (26.54%) | |

| Upper secondary | 25 (11.85%) | 11 (5.21%) | 38 (18.01%) | 74 (35.07%) | |

| Higher | 9 (4.27%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (2.37%) | 14 (6.64%) | |

| Height (Mean ± SD) | 177.84 ± 8.37 | 180.38 ± 4.64 | 178.49 ± 7.23 | 178.00 ± 7.54 | N.A. |

| Weight (Mean ± SD) | 85.15 ± 14.77 | 88.18 ± 11.58 | 84.61 ± 13.80 | 85.22 ± 14.00 | N.A. |

| Body mass index (Mean ± SD) | 26.96 ± 4.47 | 27.14 ± 3.62 | 26.56 ± 3.97 | 27.00 ± 4.15 | N.A. |

| Body mass index (No. and %) | 0.804 | ||||

| <18.5 (underweight) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.95%) | 2 (0.95%) | |

| 18.5–24.9 (normal weight) | 41 (19.43%) | 7 (3.32%) | 34 (16.11%) | 82 (38.86%) | |

| 25.0–29.9 (overweight) | 35 (16.59%) | 10 (4.74%) | 43 (20.38%) | 88 (41.71%) | |

| >29.9 (obese) | 17 (8.06%) | 5 (2.37%) | 17 (8.06%) | 39 (18.48%) | |

| Smoking (No. and %) | 0.240 | ||||

| Yes | 53 (25.12%) | 9 (4.27%) | 46 (21.80%) | 108 (51.18%) | |

| No | 40 (18.96%) | 13 (6.16%) | 50 (23.70%) | 103 (48.82%) | |

| Professional activity pre-reclusion (No. and %) | 0.473 | ||||

| Yes | 28 (13.27%) | 4 (1.90%) | 30 (14.22%) | 62 (29.38%) | |

| No | 65 (30.81%) | 18 (8.53%) | 66 (31.28%) | 149 (70.62%) |

| LPAL (n = 93) | MPAL (n = 22) | HPAL (n = 96) | Total (n = 211) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How many meals do you usually consume daily? | 0.769 | ||||

| 1 | 2 (0.95%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.47%) | 3 (1.42%) | |

| 2 | 4 (1.90%) | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (1.90%) | 8 (3.79%) | |

| 3 | 42 (19.90%) | 8 (3.79%) | 37 (17.53%) | 87 (41.23%) | |

| 4 | 24 (11.37%) | 8 (3.79%) | 28 (13.27%) | 60 (28.44%) | |

| 5 or more | 21 (9.95%) | 6 (2.84%) | 26 (12.32%) | 53 (25.12%) | |

| Do you consume meals at regular times? | 0.416 | ||||

| No | 23 (10.90%) | 2 (0,95%) | 17 (8.06%) | 42 (19,91%) | |

| Yes, but only some of them | 34 (16.11%) | 10 (4.74%) | 43 (20.38%) | 87 (41.23%) | |

| Yes, all of them | 36 (17.06%) | 10 (4.74%) | 36 (17.06%) | 82 (38.86%) | |

| How often do you snack between the meals? | 0.345 | ||||

| Never | 4 (1.90%) | 3 (1.42%) | 11 (5.21%) | 18 (8.53%) | |

| 1–3 times per month | 24 (11.37%) | 7 (3.32%) | 16 (7.58%) | 47 (22.27%) | |

| Once per week | 10 (4.74%) | 1 (0.47%) | 14 (6.64%) | 25 (11.85%) | |

| Few times per week | 17 (8.06%) | 5 (2.37%) | 19 (9.00%) | 41 (19.43%) | |

| Once per day | 14 (6.64%) | 3 (1.42%) | 19 (9.00%) | 36 (17.06%) | |

| Few times per day | 24 (11.37%) | 3 (1.42%) | 17 (8.06%) | 44 (20.85%) | |

| What types of food do you usually consume between the meals during the weekdays? | |||||

| Fruit | 43 (22.28%) | 13(6.74%) | 38 (19.69%) | 94 (48.70%) | 0.372 |

| Vegetables | 18 (9.33%) | 9 (4.66%) | 21 (10.88%) | 48 (24.87%) | 0.215 |

| Unsweetened dairy beverages and desserts | 26 (13.47%) | 4 (2.07%) | 18 (9.33%) | 48 (24.87%) | 0.250 |

| Sweetened dairy beverages and desserts | 28 (14.51%) | 5 (2.59%) | 27 (13.99%) | 60 (31.09%) | 0.815 |

| Sweet snacks | 36 (18.65%) | 9 (4.66%) | 42 (21.76%) | 87 (45.08%) | 0.697 |

| Savory snacks | 22 (11.40%) | 5 (2.59%) | 23 (11.92%) | 50 (25.91%) | 0.983 |

| Nuts, almonds, seeds | 25 (12.95%) | 5 (2.59%) | 19 (9.84%) | 49 (25.39%) | 0.464 |

| Other | 10 (5.18%) | 0 (0.00%) | 7 (3.63%) | 17 (8.81%) | 0.193 |

| Do you add any sugar to your hot beverages? | 0.578 | ||||

| No | 33 (15.63%) | 6 (2.84%) | 36 (17.06%) | 75 (35.55%) | |

| Yes, I add one teaspoon of sugar (or honey) | 22 (10.43%) | 5 (2.37%) | 19 (9.00%) | 46 (21.80%) | |

| Yes, I add two or more teaspoons of sugar (or honey) | 24 (11.37%) | 8 (3.79%) | 25 (11.85%) | 57 (27.01%) | |

| Yes, I use sweeteners (low-caloric substitute for sugar) | 16 (7.58%) | 3 (1.42%) | 14 (6.63%) | 33 (15.64%) | |

| Do you add salt to your meals and sandwiches once prepared? | 0.193 | ||||

| No | 25 (11.85%) | 6 (2.84%) | 41 (19.43%) | 72 (34.12%) | |

| Yes, but only sometimes | 52 (24.64%) | 12 (5.69%) | 41 (19.43%) | 105 (49.76%) | |

| Yes, I add salt to most of my meals | 16 (7.58%) | 4 (1.90%) | 14 (6.64%) | 34 (16.11%) | |

| Are you currently following a diet? | 0.300 | ||||

| No | 76 (36.02%) | 17 (8.06%) | 78 (36.97%) | 171 (81.04%) | |

| Yes, as advised by my doctor for medical reasons | 7 (3.32%) | 1 (0.47%) | 12 (5.69%) | 20 (9.48%) | |

| Yes, it was my personal decision | 10 (4.74%) | 4 (1.90%) | 6 (2.84%) | 20 (9.48%) |

| LPAL (n = 93) | MPAL (n = 22) | HPAL (n = 96) | Total (n = 211) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweetened hot beverages (black tea, coffee, herbal or fruit teas) | 0.978 | ||||

| Never | 11 (5.21%) | 4 (1.90%) | 13 (6.16%) | 28 (13.27%) | |

| 1–3 times per month | 8 (3.79%) | 3 (1.42%) | 6 (2.84%) | 17 (8.06%) | |

| Once per week | 7 (3.32%) | 2 (0.95%) | 6 (2.84%) | 15 (7.11%) | |

| Few times per week | 16 (7.58%) | 3 (1.42%) | 15 (7.11%) | 34 (16.11%) | |

| Once per day | 12 (5.69%) | 3 (1.42%) | 16 (7.58%) | 31 (14.69%) | |

| Few times per day | 39 (18.48%) | 7 (3.32%) | 40 (18.96%) | 86 (40.76%) | |

| Sweetened carbonated or still beverages | 0.091 | ||||

| Never | 29 (13.74%) | 6 (2.84%) | 20 (9.48%) | 55 (26.07%) | |

| 1–3 times per month | 22 (10.43%) | 5 (2.37%) | 30 (14.22%) | 57 (27.01%) | |

| Once per week | 14 (6.64%) | 4 (1.90%) | 17 (8.06%) | 35 (16.59%) | |

| Few times per week | 18 (8.53%) | 2 (0.95%) | 20 (9.48%) | 40 (18.96%) | |

| Once per day | 6 (2.84%) | 0 (0.00%) | 5 (2.37%) | 11 (5.21%) | |

| Few times per day | 4 (1.90%) | 5 (2.37%) | 4 (1.90%) | 13 (6.16%) | |

| Energy drinks | 0.175 | ||||

| Never | 54 (25.59%) | 9 (4.27%) | 55 (26.07%) | 118 (55.92%) | |

| 1–3 times per month | 15 (7.11%) | 7 (3.32%) | 14 (6.64%) | 36 (17.06%) | |

| Once per week | 7 (3.32%) | 4 (1.90%) | 8 (3.79%) | 19 (9.00%) | |

| Few times per week | 12 (5.69%) | 0 (0.00%) | 13 (6.16%) | 25 (11.85%) | |

| Once per day | 2 (0.95%) | 0 (0.00%) | 6 (2.84%) | 8 (3.79%) | |

| Few times per day | 3 (1.42%) | 2 (0.95%) | 0 (0.00%) | 5 (2.37%) | |

| Fruit juices | 0.622 | ||||

| Never | 16 (7.58%) | 3 (1.42%) | 22 (10.43%) | 41 (19.43%) | |

| 1–3 times per month | 22 (10.43%) | 4 (1.90%) | 32 (15.17%) | 58 (27.49%) | |

| Once per week | 23 (10.90%) | 5 (2.37%) | 14 (6.64%) | 42 (19.91%) | |

| Few times per week | 23 (10.90%) | 6 (2.84%) | 18 (8.53%) | 47 (22.27%) | |

| Once per day | 6 (2.84%) | 2 (0.95%) | 7 (3.32%) | 15 (7.11%) | |

| Few times per day | 3 (1.42%) | 2 (0.95%) | 3 (1.42%) | 8 (3.79%) | |

| Vegetable juices or fruit and vegetable juices | 0.402 | ||||

| Never | 30 (14.22%) | 5 (2.37%) | 34 (16.11%) | 69 (32.70%) | |

| 1–3 times per month | 28 (13.27%) | 7 (3.32%) | 24 (11.37%) | 59 (27.96%) | |

| Once per week | 14 (6.64%) | 2 (0.95%) | 16 (7.58%) | 32 (15.17%) | |

| Few times per week | 13 (6.16%) | 2 (0.95%) | 14 (6.64%) | 29 (13.74%) | |

| Once per day | 6 (2.84%) | 3 (1.42%) | 4 (1.90%) | 13 (6.16%) | |

| Few times per day | 2 (0.95%) | 3 (1.42%) | 4 (1.90%) | 9 (4.27%) | |

| Sweets (confectionary, biscuits, cakes, chocolate bars, cereal bars, other) | 0.901 | ||||

| Never | 10 (4.74%) | 2 (0.95%) | 5 (2.37%) | 17 (8.06%) | |

| 1–3 times per month | 17 (8.07%) | 4 (1.90%) | 19 (9.00%) | 40 (18.96%) | |

| Once per week | 16 (7.58%) | 6 (2.84%) | 13 (6.16%) | 35 (16.59%) | |

| Few times per week | 34 (16.11%) | 7 (3.32%) | 41 (19.43%) | 82 (38.86%) | |

| Once per day | 11 (5.21%) | 2 (0.95%) | 12 (5.69%) | 25 (11.85%) | |

| Few times per day | 5 (2.37%) | 1 (0.47%) | 6 (2.84%) | 12 (5.69%) |

| LPAL (n = 93) | MPAL (n = 22) | HPAL (n = 96) | Total (n = 211) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported nutrition knowledge level | 0.500 | ||||

| Insufficient | 17 (8.06%) | 4 (1.90%) | 17 (8.06%) | 38 (18.01%) | |

| Sufficient | 44 (20.85%) | 7 (3.32%) | 42 (19.91%) | 93 (44.08%) | |

| Good | 29 (13.74%) | 11 (5.21%) | 35 (18.59%) | 75 (35.55%) | |

| Very good | 3 (1.42%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (0.95%) | 5 (2.37%) | |

| Nutrition knowledge level | 0.367 | ||||

| Insufficient | 25 (11.85%) | 8 (3.79%) | 25 (11.85%) | 58 (27.49%) | |

| Sufficient | 53 (25.12%) | 13 (6.16%) | 69 (32.70%) | 135 (63.98%) | |

| Good | 15 (7.11%) | 1 (0.47%) | 2 (0.95%) | 18 (8.53%) |

| LPAL (n = 93) | MPAL (n = 22) | HPAL (n = 96) | Total (n = 211) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-Healthy Diet Index | 0.362 | ||||

| Low | 82 (38.86%) | 19 (9.00%) | 87 (41.23%) | 188 (89.10%) | |

| Medium | 11 (5.21%) | 2 (0.95%) | 8 (3.80%) | 21 (9.95%) | |

| High | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.47%) | 1 (0.47%) | 2 (0.95%) | |

| Non-Healthy Diet Index | 0.344 | ||||

| Low | 90 (42.65%) | 20 (9.48%) | 91 (43.13%) | 201 (95.26%) | |

| Medium | 3 (1.42%) | 1 (0.47%) | 4 (1.90%) | 8 (3.80%) | |

| High | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (0.47%) | 1 (0.47%) | 2 (0.95%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosendiak, A.; Stanikowski, P.; Domagała, D.; Gustaw, W.; Bronkowska, M. Dietary Habits, Diet Quality, Nutrition Knowledge, and Associations with Physical Activity in Polish Prisoners: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031422

Kosendiak A, Stanikowski P, Domagała D, Gustaw W, Bronkowska M. Dietary Habits, Diet Quality, Nutrition Knowledge, and Associations with Physical Activity in Polish Prisoners: A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031422

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosendiak, Aureliusz, Piotr Stanikowski, Dorota Domagała, Waldemar Gustaw, and Monika Bronkowska. 2022. "Dietary Habits, Diet Quality, Nutrition Knowledge, and Associations with Physical Activity in Polish Prisoners: A Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 3: 1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031422

APA StyleKosendiak, A., Stanikowski, P., Domagała, D., Gustaw, W., & Bronkowska, M. (2022). Dietary Habits, Diet Quality, Nutrition Knowledge, and Associations with Physical Activity in Polish Prisoners: A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031422