Evaluation of a Complex Intervention to Strengthen Participation-Centred Care for Children with Special Healthcare Needs: Protocol of the Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised PART-CHILD Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives

- (1)

- assess the effectiveness of the PART-CHILD intervention to improve perceived SDM with parents (primary endpoint) and explore effectiveness in a variety of secondary endpoints (e.g., participation) related to the framework for participation-centred care (effectiveness evaluation) and

- (2)

- explore (a) implementation of the PART-CHILD intervention, (b) its mechanisms of impact and (c) contextual factors potentially moderating intervention effectiveness (process evaluation).

2. Intervention

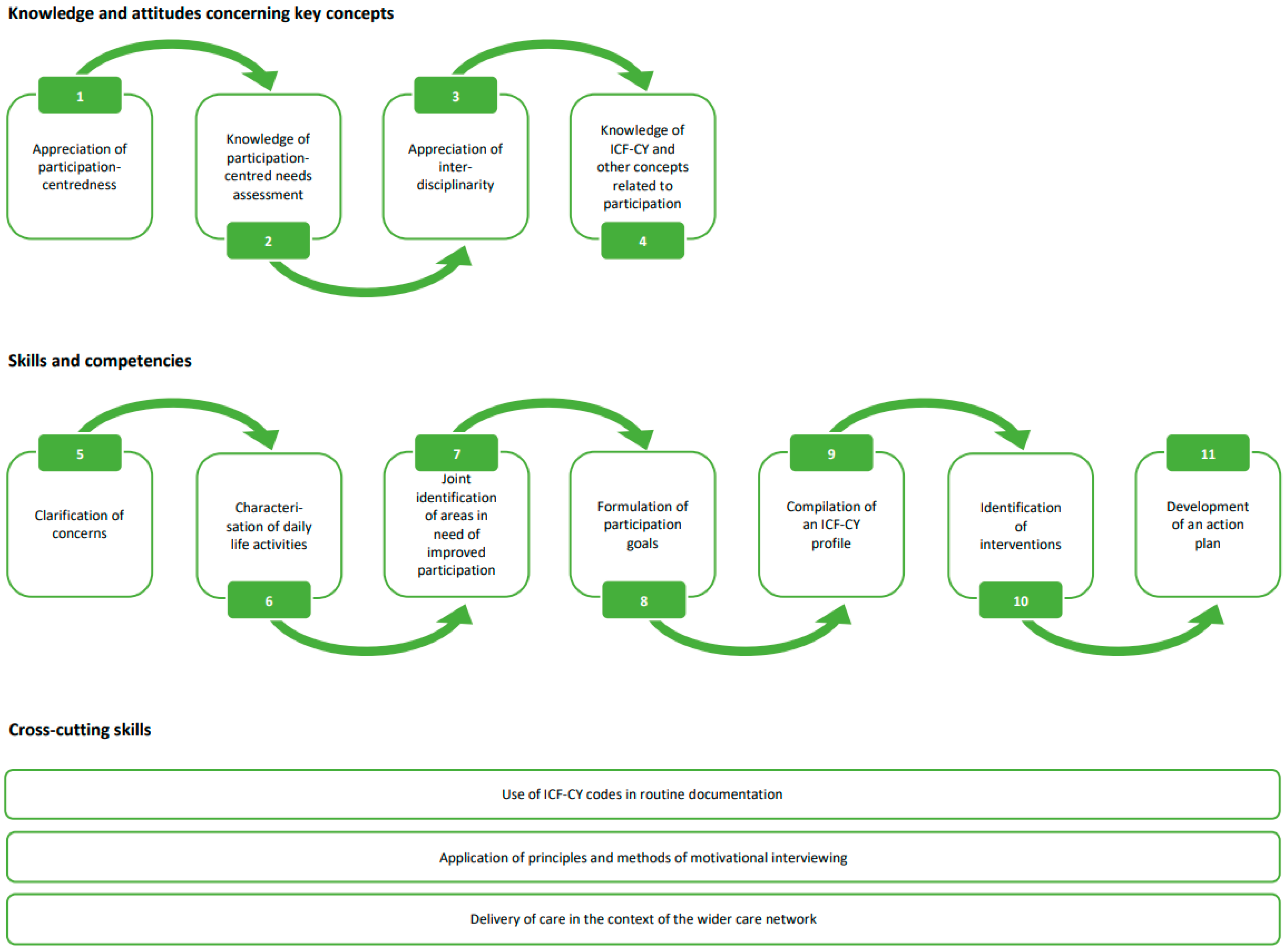

2.1. Module 1: Team Training

2.2. Module 2: Documentation Software ICF-AddIn

2.3. Module 3: Implementation Support

3. Methods and Analysis

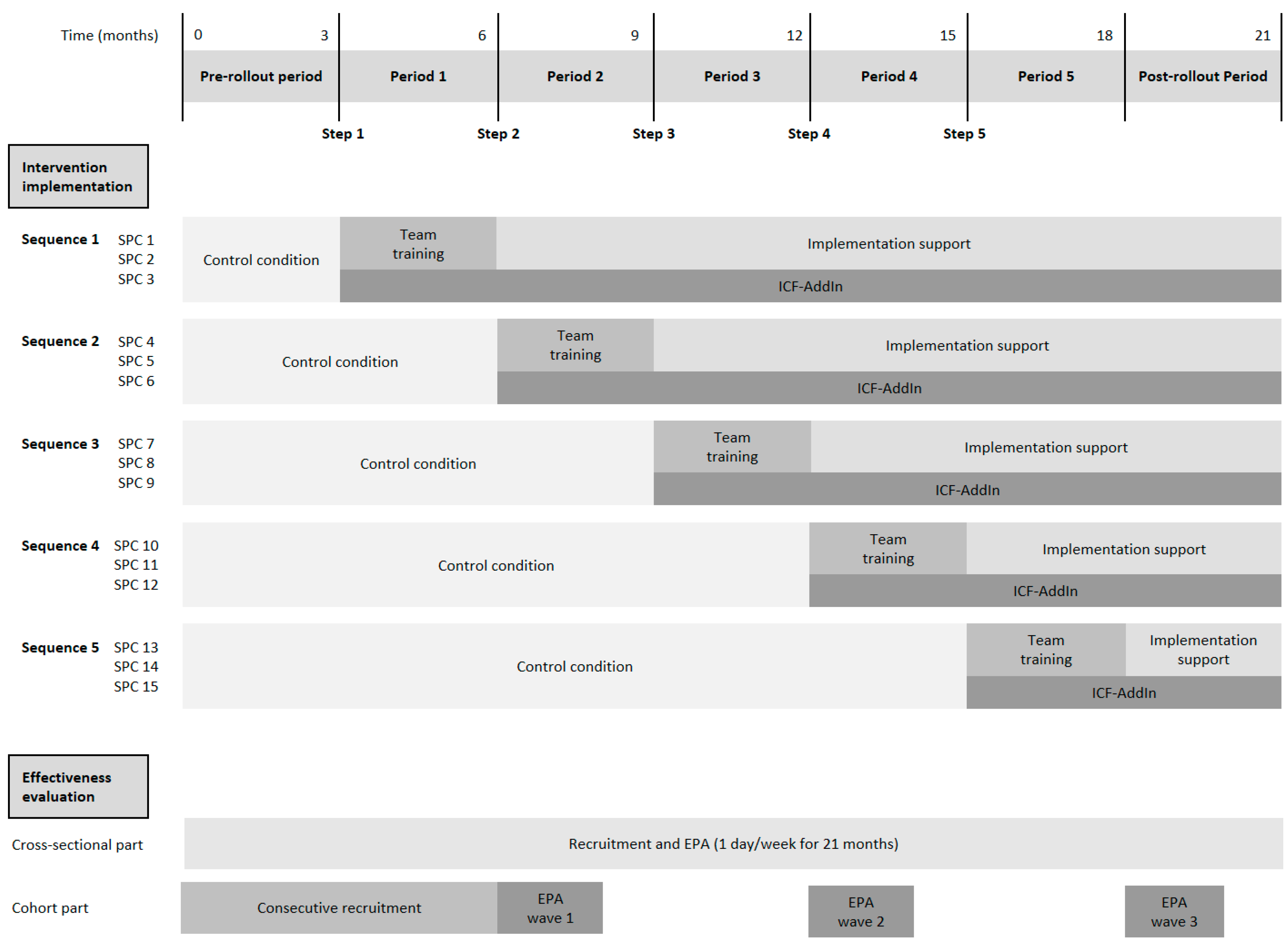

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Reporting

3.3. Ethical Considerations

3.4. Setting

3.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Study Sites

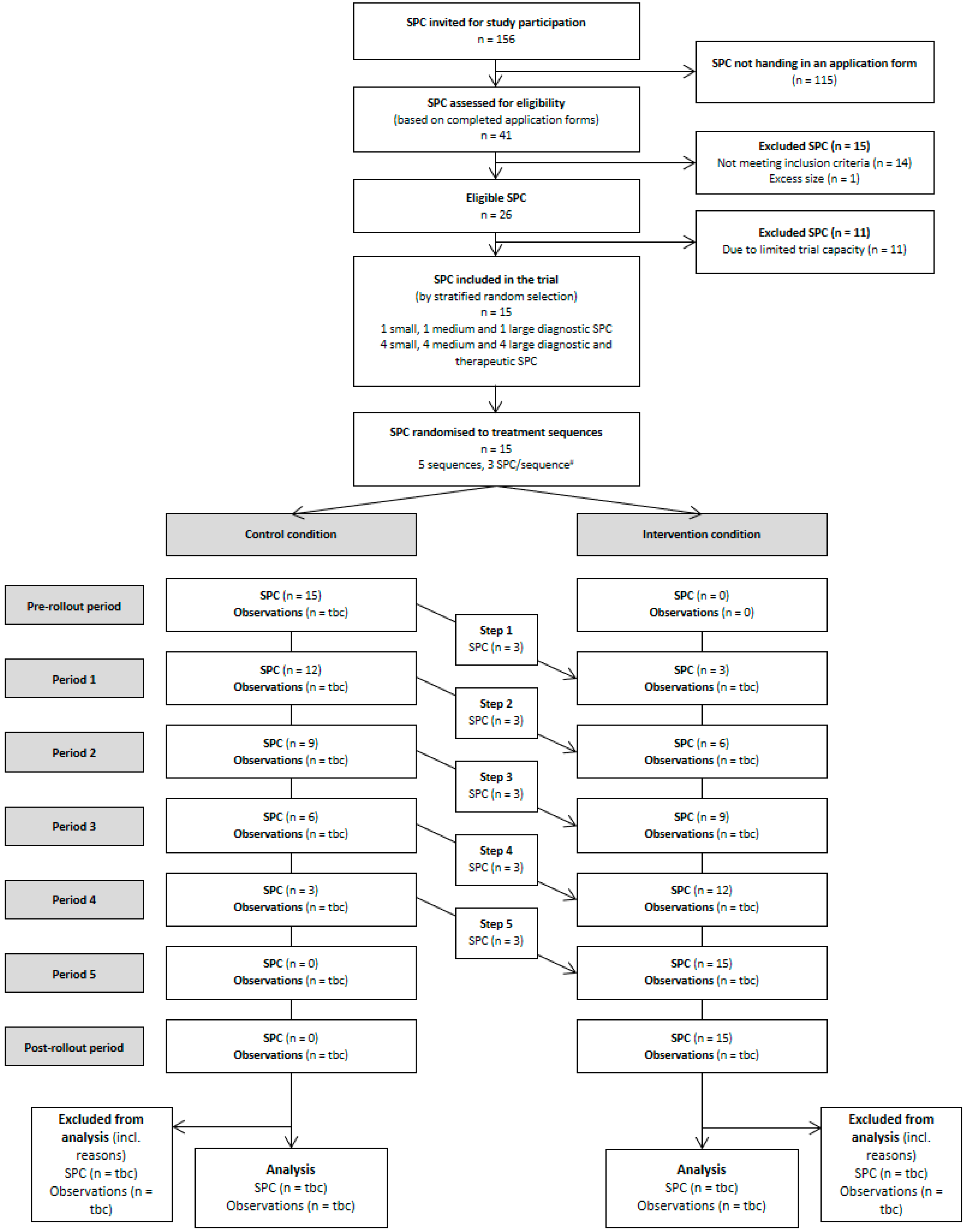

3.6. Recruitment and Selection of Study Sites

3.7. Logic Model

3.8. Effectiveness Evaluation

3.8.1. Evaluation Design

3.8.2. Randomisation

3.8.3. Allocation Concealment and Blinding

3.8.4. Sample Size Considerations

3.8.5. Participants

Cross-Sectional Component

Cohort Component

3.8.6. Recruitment and Data Collection

Cross-Sectional Component

Cohort Component

3.8.7. Endpoints

3.8.8. Statistical Analyses

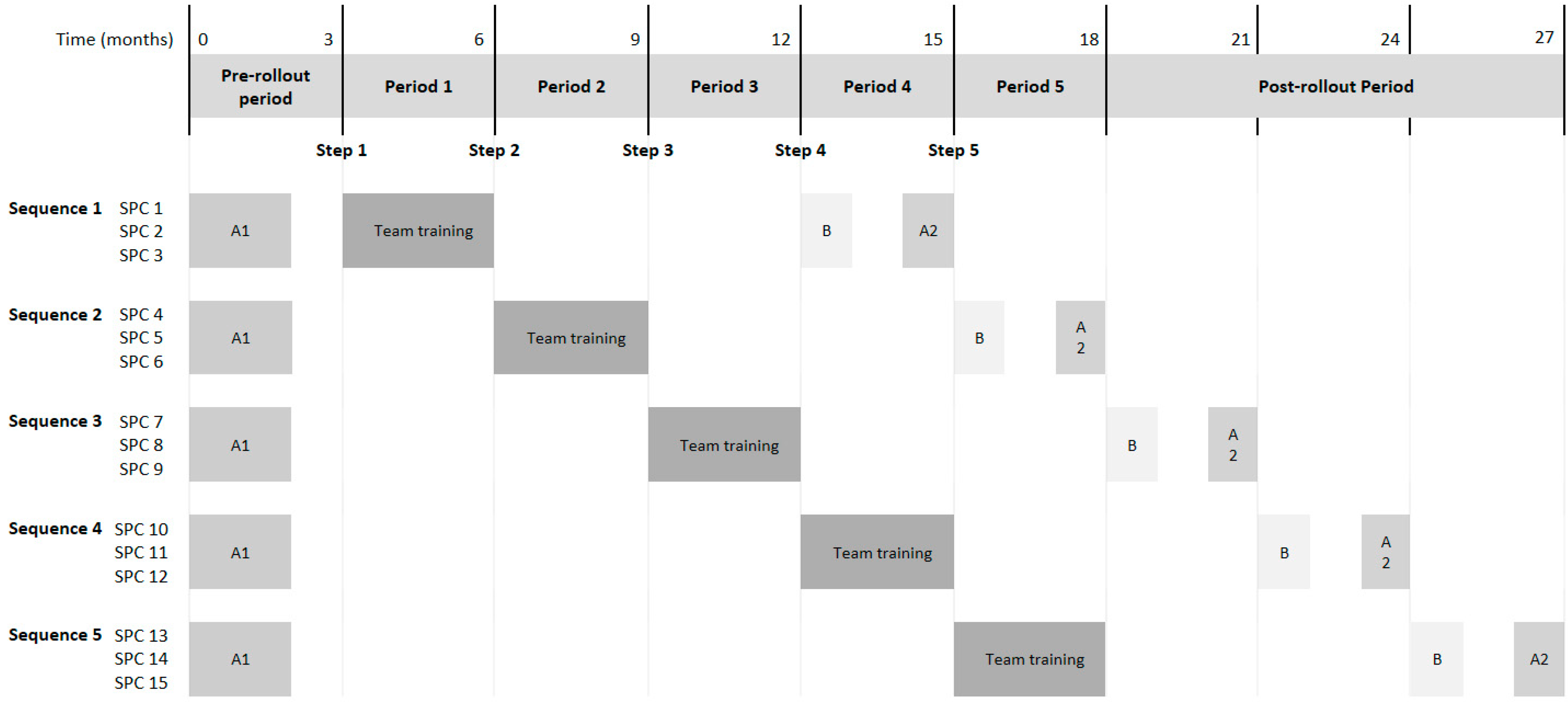

3.9. Process Evaluation

3.9.1. Participant Recruitment and Data Collection

Surveys among SPC Directors and Their Staff

Semi-Structured Interviews with SPC Directors and Their Staff

3.9.2. Outcomes

Surveys among SPC Directors and Their Staff

Semi-Structured Interviews with SPC Directors and Their Staff

3.9.3. Analysis

Surveys among SPC Directors and Their Staff

Semi-Structured Interviews with SPC Directors and Staff

Implementation Notes, ICF-AddIn Usage and Consultation Observations

3.10. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Data

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stucki, G. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF): A Promising Framework and Classification for Rehabilitation Medicine. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 84, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children & Youth Version; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- De Róiste, A.; Kelly, C.; Molcho, M.; Gavin, A.; Nic Gabhainn, S. Is School Participation Good for Children? Associations with Health and Wellbeing. Health Educ. 2012, 112, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Eccles, J.S. Is Extracurricular Participation Associated with Beneficial Outcomes? Concurrent and Longitudinal Relations. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M. Participation in the Occupations of Everyday Life. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2002, 56, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Solish, A.; Perry, A.; Minnes, P. Participation of Children with and without Disabilities in Social, Recreational and Leisure Activities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2009, 23, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, A.; Perry, A.; Minnes, P.M. Examining the Social Participation of Children and Adolescents with Intellectual Disabilities and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Relation to Peers: Social Participation of Children with ID and ASD. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2016, 60, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedell, G.M.; Dumas, H. Social Participation of Children and Youth with Acquired Brain Injuries Discharged from Inpatient Rehabilitation: A Follow-up Study. Brain Inj. 2004, 18, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, M.; Pijl, S.J.; Nakken, H.; Van Houten, E. Social Participation of Students with Special Needs in Regular Primary Education in the Netherlands. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2010, 57, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, K.; Rapp, M.; Muehlan, H.; Spiegler, J.; Thyen, U. Frequency of Participation and Association with Functioning in Adolescents Born Extremely Preterm—Findings from a Population-Based Cohort in Northern Germany. Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 120, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, P. Participation of Children with Disabilities: Measuring Subjective and Objective Outcomes. Child Care Health Dev. 2013, 39, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteneck, G.; Dijkers, M. Difficult to Measure Constructs: Conceptual and Methodological Issues Concerning Participation and Environmental Factors. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholl, I.; Zill, J.M.; Härter, M.; Dirmaier, J. An Integrative Model of Patient-Centeredness—A Systematic Review and Concept Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, P.J.; Thompson, R.; Walsh, T.; Grande, S.W.; Ozanne, E.M.; Elwyn, G. The Psychometric Properties of CollaboRATE: A Fast and Frugal Patient-Reported Measure of the Shared Decision-Making Process. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwyn, G.; Barr, P.J.; Grande, S.W.; Thompson, R.; Walsh, T.; Ozanne, E.M. Developing CollaboRATE: A Fast and Frugal Patient-Reported Measure of Shared Decision Making in Clinical Encounters. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 93, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, I. Children’s Participation in Consultations and Decision-Making at Health Service Level: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1682–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, I.; Amory, A.; Kiernan, G.; Gibson, F. Children’s Participation in Shared Decision-Making: Children, Adolescents, Parents and Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives and Experiences. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; Gallagher, P. Participation in Communication and Decision-Making: Children and Young People’s Experiences in a Hospital Setting. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 2334–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, M.; Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raymond, É. Inventory and Analysis of Definitions of Social Participation Found in the Aging Literature: Proposed Taxonomy of Social Activities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geenen, S.; Powers, L.E.; Powers, J.; Cunningham, M.; McMahon, L.; Nelson, M.; Dalton, L.D.; Swank, P.; Fullerton, A.; Other members of the Research Consortium to Increase the Success of Youth in Foster Care. Experimental Study of a Self-Determination Intervention for Youth in Foster Care. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 2013, 36, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuang, Y.-P.; Ho, G.-S.; Su, C.-Y. Occupational Therapy Home Program for Children with Intellectual Disabilities: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, B.; Ullenhag, A.; Keen, D.; Granlund, M.; Imms, C. The Effect of Interventions Aimed at Improving Participation Outcomes for Children with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2015, 57, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guli, L.A.; Semrud-Clikeman, M.; Lerner, M.D.; Britton, N. Social Competence Intervention Program (SCIP): A Pilot Study of a Creative Drama Program for Youth with Social Difficulties. Arts Psychother. 2013, 40, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylor, C.; Darling-White, M. Achieving Participation-Focused Intervention through Shared Decision Making: Proposal of an Age- and Disorder-Generic Framework. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2020, 29, 1335–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suls, J.; Rothman, A. Evolution of the Biopsychosocial Model: Prospects and Challenges for Health Psychology. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawe, P.; Shiell, A.; Riley, T. Complex Interventions: How “out of Control” Can a Randomised Controlled Trial Be? BMJ 2004, 328, 1561–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.J.; Waltz, T.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Damschroder, L.J.; Smith, J.L.; Matthieu, M.M.; Proctor, E.K.; Kirchner, J.E. A Refined Compilation of Implementation Strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) Project. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: The New Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hemming, K.; Taljaard, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Hooper, R.; Copas, A.; Thompson, J.A.; Dixon-Woods, M.; Aldcroft, A.; Doussau, A.; Grayling, M.; et al. Reporting of Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised Trials: Extension of the CONSORT 2010 Statement with Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ 2018, 363, k1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.-W.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Altman, D.G.; Laupacis, A.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Krleža-Jerić, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Mann, H.; Dickersin, K.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. SPIRIT 2013 Statement: Defining Standard Protocol Items for Clinical Trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WK Kellogg Foundation. Logic Model Development Guide; WK Kellogg Foundation: Battle Creek, MI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, G.F.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; Wight, D.; et al. Process Evaluation of Complex Interventions: UK Medical Research Council (MRC) Guidance. BMJ 2015, 350, h1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrler, A.; Hoffmann, D.U.; Görig, T.; Georg, S.; König, J.; Urschitz, M.S.; De Bock, F.; Eichinger, M. Assessing the Extent of Shared Decision Making in Pediatrics: Preliminary Psychometric Evaluation of the German CollaboRATEpediatric Scales for Patients Aged 7-18 Years, Parents and Parent-Proxy Reports. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobbs, C.; Spittle, A.; Johnston, L. Eat, Sleep, Play, Connect—Participation Outcome Measures for Infants Birth to Two Years: A Systematic Review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlan, H.; Golke, H.; Bullinger, M.; Thyen, U.; Schmidt, S. Development and Validation of a Short Measure of the CHC-SUN Assessing Health Care Satisfaction in Adolescents. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 196–197. [Google Scholar]

- De Bock, F.; Bosle, C.; Graef, C.; Oepen, J.; Philippi, H.; Urschitz, M.S. Measuring Social Participation in Children with Chronic Health Conditions: Validation and Reference Values of the Child and Adolescent Scale of Participation (CASP) in the German Context. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S. The DISABKIDS Questionnaires: Quality of Live Questionnaires for Children with Chronic Conditions; Pabst Science Publishers: Lengerich, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S.; Thyen, U.; Chaplin, J.; Mueller-Godeffroy, E.; European DISABKIDS Group. Cross-Cultural Development of a Child Health Care Questionnaire on Satisfaction, Utilization, and Needs. Ambul. Pediatr. 2007, 7, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliege, H.; Rose, M.; Arck, P.; Levenstein, S.; Klapp, B.F. Validation of the “Perceived Stress Questionnaire“ (PSQ) in a German cohort. Diagnostica 2001, 47, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancl, L.A.; DeRouen, T.A. A Covariance Estimator for GEE with Improved Small-sample Properties. Biometrics 2001, 57, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Harden, S.M.; Gaglio, B.; Rabin, B.; Smith, M.L.; Porter, G.C.; Ory, M.G.; Estabrooks, P.A. RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice with a 20-Year Review. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, C.M.; Jacobs, S.R.; Esserman, D.A.; Bruce, K.; Weiner, B.J. Organizational Readiness for Implementing Change: A Psychometric Assessment of a New Measure. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammuto, R.F.; Krakower, J.Y. Quantitative and Qualitative Studies of Organizational Culture. In Research in Organizational Change and Development: An Annual Series Featuring Advances in Theory, Methodology and Research; Pasmore, W.A., Woodman, R.W., Eds.; JAI Press Inc.: Stamford, CT, USA, 1991; pp. 83–114. [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz, J.E.; Winblad, U.; Arnetz, B.B.; Höglund, A.T. Physicians’ and Nurses’ Perceptions of Patient Involvement in Myocardial Infarction Care. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2008, 7, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.S.; Konrad, T.R.; Linzer, M.; McMurray, J.; Pathman, D.E.; Gerrity, M.; Schwartz, M.D.; Scheckler, W.E.; Van Kirk, J.; Rhodes, E.; et al. Refining the Measurement of Physician Job Satisfaction: Results from the Physician Worklife Survey. Med. Care 1999, 37, 1140–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken; 12., überarbeitete Auflage; Beltz Verlag: Basel, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brueck, R.K.; Frick, K.; Loessl, B.; Kriston, L.; Schondelmaier, S.; Go, C.; Haerter, M.; Berner, M. Psychometric Properties of the German Version of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2009, 36, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosterveld-Vlug, M.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.; ten Koppel, M.; van Hout, H.; Smets, T.; Pivodic, L.; Tanghe, M.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Hockley, J.; Payne, S.; et al. Evaluating the Implementation of the PACE Steps to Success Programme in Long-Term Care Facilities in Seven Countries According to the RE-AIM Framework. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, J.M.; Kaelin, V.C.; Anaby, D.; Teplicky, R.; Khetani, M.A. Electronic Participation-focused Care Planning Support for Families: A Pilot Study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobbs, C.A.; Spittle, A.J.; Johnston, L.M. PreEMPT (Preterm Infant Early Intervention for Movement and Participation Trial): The Feasibility of a Novel, Participation-Focused Early Physiotherapy Intervention Supported by Telehealth in Regional Australia—A Protocol. Open J. Pediatr. 2020, 10, 707–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, J.H.H.; Kerbl, R.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Lenton, S. Opening the Debate on Pediatric Subspecialties and Specialist Centers: Opportunities for Better Care or Risks of Care Fragmentation? J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 1177–1178.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, D.A.; Glasgow, R.E.; Stange, K.C. The Dynamic Sustainability Framework: Addressing the Paradox of Sustainment amid Ongoing Change. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements of the Implementation Support | Corresponding ERIC Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|

| Coaching for the SPC director | Involve executive boards |

| Coaching for local working groups implementing training content | Identify and prepare champions Organize implementation team meetings Promote adaptability |

| Team training for new staff members | Conduct ongoing training |

| Training for administrative staff not covered in module 1 | Conduct ongoing training |

| Online peer exchange across study sites | Create a learning cooperative Capture and share local knowledge Promote network weaving |

| Refresher training on the ICF-AddIn | Conduct ongoing training |

| Advanced training in motivational interviewing | Conduct ongoing training |

| Advanced training in ICF-based documen-tation and participation goal setting | Conduct ongoing training |

| Endpoint | Instrument | Validation Study | Child Survey | Parent Survey |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional component | ||||

| Primary endpoint | ||||

| Perceived SDM with parents | Parent scale of CollaboRATEpediatric | [37] | X | |

| Secondary endpoints | ||||

| Perceived SDM with patients (if aged 7 years or older) | Paediatric patient scale of CollaboRATEpediatric | [37] | X | |

| Parental satisfaction with care | CHC-SUN short form | [39] | X | |

| Patients’ satisfaction with care (if aged 7 years or older) | YHC-SUN short form | [39] | X | |

| Cohort component | ||||

| Secondary endpoints | ||||

| Participation of patients | CASP | [40] | X | |

| Health-related quality of life of patients | DISABKIDS-10 parent-report scale | [41] | X | |

| DISABKIDS-10 patient scale | [41] | X | ||

| Utilisation of healthcare services and unmet needs | CHC-SUN long form | [42] | X | |

| Perceived parental stress | PSQ | [43] | X |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eichinger, M.; Görig, T.; Georg, S.; Hoffmann, D.; Sonntag, D.; Philippi, H.; König, J.; Urschitz, M.S.; De Bock, F. Evaluation of a Complex Intervention to Strengthen Participation-Centred Care for Children with Special Healthcare Needs: Protocol of the Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised PART-CHILD Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416865

Eichinger M, Görig T, Georg S, Hoffmann D, Sonntag D, Philippi H, König J, Urschitz MS, De Bock F. Evaluation of a Complex Intervention to Strengthen Participation-Centred Care for Children with Special Healthcare Needs: Protocol of the Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised PART-CHILD Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416865

Chicago/Turabian StyleEichinger, Michael, Tatiana Görig, Sabine Georg, Dorle Hoffmann, Diana Sonntag, Heike Philippi, Jochem König, Michael S. Urschitz, and Freia De Bock. 2022. "Evaluation of a Complex Intervention to Strengthen Participation-Centred Care for Children with Special Healthcare Needs: Protocol of the Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised PART-CHILD Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416865

APA StyleEichinger, M., Görig, T., Georg, S., Hoffmann, D., Sonntag, D., Philippi, H., König, J., Urschitz, M. S., & De Bock, F. (2022). Evaluation of a Complex Intervention to Strengthen Participation-Centred Care for Children with Special Healthcare Needs: Protocol of the Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised PART-CHILD Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416865