Life Satisfaction of Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland

Abstract

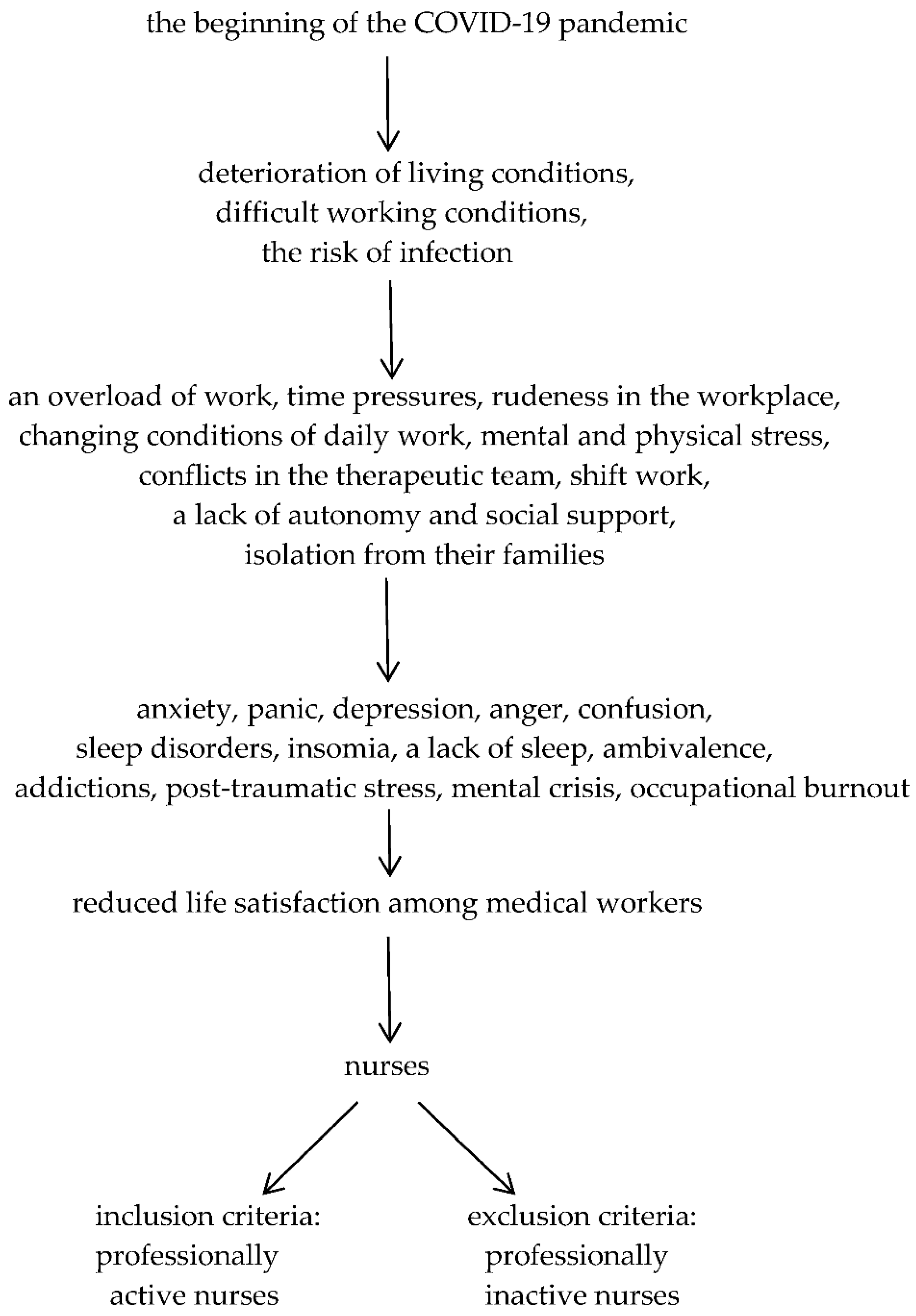

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting and Participants

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. An Author’s Questionnaire

2.2.2. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Nurses

3.2. Satisfaction with Life

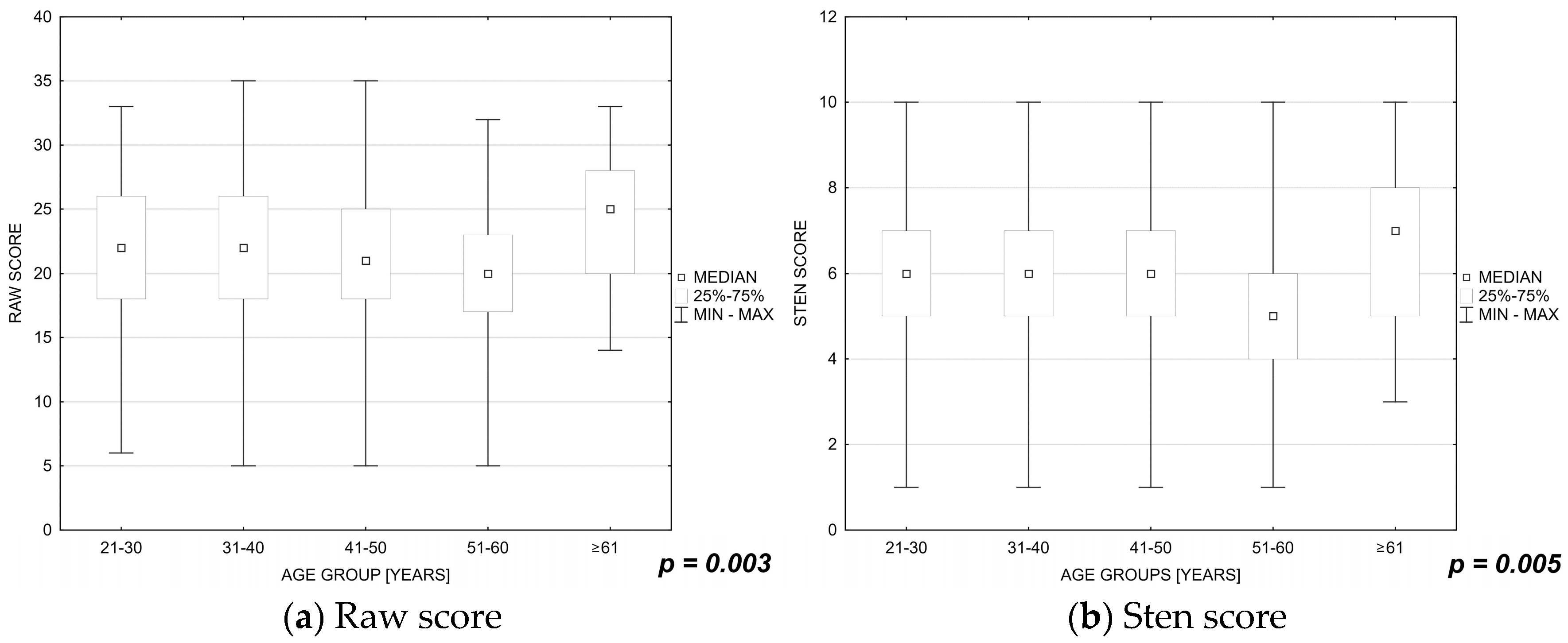

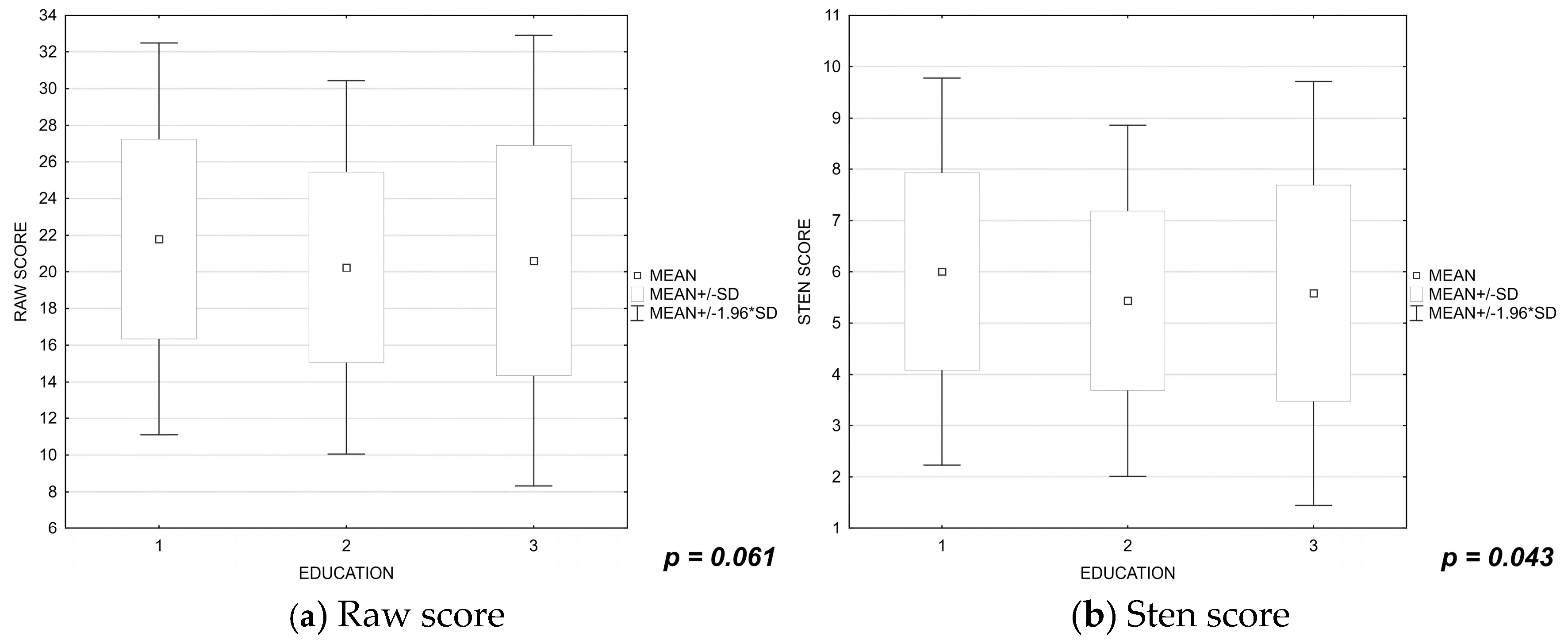

3.3. Influence of Various Factors on Satisfaction with Life

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Naming the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and the Virus that Causes it. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(COVID-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Mo, D.; Xiao, X. The risk factors for the exacerbation of COVID-19 disease: A case–control study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 30, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baud, D.; Qi, X.; Nielsen-Saines, K.; Musso, D.; Pomar, L.; Favre, G. Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, S.; Xie, N.; Yao, L.; Cao, Y.; Day, S.W.; Howard, S.C.; Graff, J.C.; Gu, T.; et al. The data set for patient information based algorithm to predict mortality cause by COVID-19. Data Brief. 2020, 30, 105619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galehdar, N.; Toulabi, T.; Kamran, A.; Heydari, H. Exploring nurses’ perception of taking care of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A qualitative study. Nurs. Open 2020, 8, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkiewicz, J.; Mackiewicz, B.; Lemieszek, M.K. COVID 19: Possible interrelations with respiratory comorbidities caused by occupational exposure to various hazardous bioaerosols. Part I. Occurrence, epidemiology and presumed origin of the pandemic. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.X.; Liu, J.; Jahanshahi, A.A.; Nawaser, K.; Yousefi, A.; Li, J.; Sun, S. At the height of the storm: Healthcare staff’s health conditions and job satisfaction and their associated predictors during the epidemic peak of COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mejia, C.R.; Delgado-Zegarra, J.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Arce-Esquivel, A.A.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J.; Rosas Del Portal, M.; Villegas, L.F.; Curioso, W.H.; Sekar, M.C.; et al. The Peru approach against the COVID-19 infodemic: Insights and strategies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Murphy, M. Going viral: Doctors must tackle fake news in the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020, 369, m1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, S.X.; Jahanshahi, A.A.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Dai, H.; Li, J.; Ibarra, V.G. Belief in a COVID-19 conspiracy theory as a predictor of mental health and well-being of health care workers in Ecuador: Cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e20737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Martin, P.; Prieto-Flores, M.E.; Forjaz, M.J.; Fernandez-Mayoralas, G.; Rojo-Perez, F.; Rojo, J.M.; Ayala, A. Components and determinants of quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Eur. J. Ageing 2012, 9, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hage, W.; Hingray, C.; Lemogne, C.; Yrondi, A.; Brunault, P.; Bienvenu, T.; Etain, B.; Paquet, C.; Gohier, B.; Bennabi, D.; et al. Health professionals facing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: What are the mental health risks? L’Encephale 2020, 46, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosydar-Bochenek, J.; Krupa, S.; Favieri, F.; Forte, G.; Medrzycka-Dabrowska, W. Polish Version of the Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Related to COVID-19 Questionnaire COVID-19-PTSD. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 868191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, M.A.; Pereira, F.H.; DE Souza Caliari, J.; Oliveira, H.C.; Ceolim, M.F.; Andrechuk, C.R.S. Sleep and Professional Burnout in Nurses, Nursing Technicians, and Nursing Assistants During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 30, e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagini, L.; Bruno, R.M.; Gemignani, A.; Baglioni, C.; Ghiadoni, L.; Riemann, D. Sleep loss and hypertension: A systematic review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, S.; Filip, D.; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W.; Lewandowska, K.; Witt, P.; Ozga, D. Sleep disorders among nurses and other health care workers in Poland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2021, 59, 151412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiernik, E.; Nabi, H.; Pannier, B.; Czernichow, S.; Hanon, O.; Simon, T.; Simon, J.M.; Thomas, F.; Ducolombier, C.; Danchin, N.; et al. Perceived stress, sex and occupational status interact to increase the risk of future high blood pressure: The IPC cohort study. J. Hypertens. 2014, 32, 1979–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, V.; Durante, A.; Ambrosca, R.; Arcadi, P.; Graziano, G.; Pucciarelli, G.; Simeone, S.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R.; Cicolini, G. Anxiety, sleep disorders and self-efficacy among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: A large cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.; Lancee, W.J.; Balderson, K.E.; Bennett, J.P.; Borgundvaag, B.; Evans, S.; Fernandes, C.M.; Goldbloom, D.S.; Gupta, M.; Hunter, J.J.; et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1924–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.W.; Pang, E.P.; Lam, L.C.; Chiu, H.F. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: Stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol. Med. 2004, 34, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Al Sinani, M.; Al-Lenjawi, B. Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 141, 110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, R.; Annaloro, C.; Arrigoni, C.; Ghizzardi, G.; Dellafiore, F.; Magon, A.; Maga, G.; Nania, T.; Pittella, F.; Villa, G. Burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder in frontline nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of studies published in 2020. Acta Bio. Med. Atenei. Parmensis. 2021, 92, e2021428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, M.A.; Hossini Rafsanjanipoor, S.M.; Zakeri, M.; Dehghan, M. The relationship between frontline nurses’ psychosocial status, satisfaction with life and resilience during the prevalence of COVID-19 disease. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanowicz-Bielska, A.; Słomion, M.; Rąpała, M. Analysis of Strategies for Managing Stress by Polish Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego. NPPPZ. Assessment and Diagnostic Instruments for Health Psychology Promotion. Available online: https://en.practest.com.pl/node/28876 (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Z. Skala Satysfakcji z Życia- SWLS. Adaptacja Skali Satysfakcji z Życia-SWLS. In Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia, 2nd ed.; Jurczyński, Z., Ed.; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego. SWLS—Skala Satysfakcji z Życia. Available online: https://www.practest.com.pl/swls-skala-satysfakcji-z-zycia (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Greenberg, N.; Docherty, M.; Gnanapragasam, S.; Wessely, S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020, 368, m1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazwin, M.Y.; Kavian, M.; Ahmadloo, M.; Jarchi, A.; Golchin Javadi, S.; Latifi, S.; Tavakoli, S.A.; Ghajarzadeh, M. The Association between Life Satisfaction and the Extent of Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Iranian Nurses: A Multicenter Survey. Iran J. Psychiatry 2016, 11, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sansó, N.; Galiana, L.; Oliver, A.; Tomás-Salvá, M.; Vidal-Blanco, G. Predicting Professional Quality of Life and Life Satisfaction in Spanish Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zborowska, A.; Gurowiec, P.J.; Młynarska, A.; Uchmanowicz, I. Factors Affecting Occupational Burnout Among Nurses Including Job Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction, and Life Orientation: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1761–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchmanowicz, I.; Manulik, S.; Lomper, K.; Rozensztrauch, A.; Zborowska, A.; Kolasińska, J.; Rosińczuk, J. Life satisfaction, job satisfaction, life orientation and occupational burnout among nurses and midwives in medical institutions in Poland: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabağ Aydın, A.; Fidan, H. The Effect of Nurses’ Death Anxiety on Life Satisfaction During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. J. Relig. Health 2021, 27, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.X.; Chen, J.; Afshar Jahanshahi, A.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Dai, H.; Li, J.; Patty-Tito, R.M. Succumbing to the COVID-19 Pandemic—Healthcare Workers Not Satisfied and Intend to Leave Their Jobs. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 20, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teke, N.; Özer, Z.; Bahçecioğlu Turan, G. Analysis of Health Care Personnel’s Attitudes Toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Life Satisfaction due to COVID-19 Pandemic. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2021, 35, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Socio-Demographic Data of the Participants | N (Total 361) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 342 |

| Male | 19 | |

| Age (years) | 21–30 | 57 |

| 31–40 | 59 | |

| 41–50 | 115 | |

| 51–60 | 119 | |

| ≥61 | 11 | |

| Place of residence | City | 302 |

| Village | 59 | |

| Education | Master of nursing | 165 |

| Bachelor of nursing | 103 | |

| Secondary education in nursing | 93 | |

| Place of work | Outpatient medical clinics | 63 |

| Hospital wards | 273 | |

| Hospice, health care and curative institutions | 18 | |

| Medical universities | 7 | |

| Years of employment in the profession (years) | ≤5 | 57 |

| 6–10 | 32 | |

| 11–20 | 50 | |

| ≥21 | 222 | |

| Satisfaction with Life | 1. In Most Ways, My Life Is Close to My Ideal | 2. The Conditions of My Life Are Excellent | 3. I Am Satisfied with My Life | 4. Thus Far, I have Gotten the Important Things I Want in Life | 5. If I could Live My Life over, I would Change almost Nothing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | 23 (6.4%) | 14 (3.9%) | 7 (1.9%) | 12 (3.3%) | 37 (10.3%) |

| Disagree | 45 (12.5%) | 34 (9.5%) | 16 (4.4%) | 25 (6.9%) | 50 (13.9%) |

| Slightly disagree | 59 (16.3%) | 54 (14.9%) | 26 (7.2%) | 48 (13.3%) | 73 (20.2%) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 135 (37.4%) | 107 (29.6%) | 60 (16.6%) | 59 (16.3%) | 68 (18.8%) |

| Slightly agree | 67 (18.6%) | 101 (28%) | 146 (40.5%) | 143 (39.6%) | 77 (21.3%) |

| Agree | 26 (7.1%) | 40 (11.1%) | 77 (21.3%) | 53 (14.7%) | 38 (10.5%) |

| Strongly agree | 6 (1.7%) | 11 (3%) | 29 (8.1%) | 21 (5.9%) | 18 (5%) |

| Level of Satisfaction with Life | Sten Score (Raw Score) | Number of Nurses | Level of Satisfaction with Life in Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 1 (5–9) | 11 (3.1%) | 83 (23%) |

| 2 (10–11) | 7 (1.9%) | ||

| 3 (12–14) | 26 (7.2%) | ||

| 4 (15–17) | 39 (10.8%) | ||

| Medium | 5 (18–20) | 74 (20.5%) | 159 (44.1%) |

| 6 (21–23) | 85 (23.6%) | ||

| High | 7 (24–26) | 63 (17.5%) | 119 (32.9%) |

| 8 (27–28) | 28 (7.7%) | ||

| 9 (29–30) | 14 (3.9%) | ||

| 10 (31–35) | 14 (3.8%) |

| Socio-Demographic Data | Satisfaction with Life | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Score | p | Sten Score | p | ||

| Gender | Male | 21 (18 ÷ 26) | p = 0.981 | 6 (5 ÷ 7) | p = 0.932 |

| Female | 21 (18 ÷ 25) | 6 (5 ÷ 7) | |||

| Place of residence | City | 21.1 ± 5.7 | p = 0.618 | 5.76 ± 1.97 | p = 0.542 |

| Village | 20.7 ± 5.4 | 5.59 ± 1.79 | |||

| Place of work | Paediatric wards | 20 (18 ÷ 22) | p = 0.216 | 5 (5 ÷ 6) | p = 0.221 |

| Internal diseases wards | 21 (18 ÷ 26.5) | 6 (6 ÷ 7.5) | |||

| Surgical wards | 21 (18 ÷ 25) | 6 (5 ÷ 7) | |||

| Intensive care units | 23 (17 ÷ 25) | 6 (4 ÷ 7) | |||

| Emergency departments | 22 (19 ÷ 26) | 6 (5 ÷ 7) | |||

| Psychiatric wards for adultsand children | 18 (15 ÷ 22) | 5 (3.5 ÷ 6) | |||

| Place of work | Outpatient medical clinics | 20 (18 ÷ 24) | p = 0.137 | 5 (5 ÷ 7) | p = 0.096 |

| Hospital wards (paediatric wards, surgical wards, internal diseases wards, surgical units, intensive care units for adults, emergency departments, intensive care units for children, psychiatric wards for adults, psychiatric wards for children) | 21 (18 ÷ 25) | 6 (5 ÷ 7) | |||

| Hospice, health care and curative institutions | 24 (21 ÷ 27) | 7 (6 ÷ 8) | |||

| Medical universities | 22 (20 ÷ 23) | 6 (5 ÷ 6) | |||

| Years of employment in the profession (years) | ≤5 | 21.5 ± 6.1 | p = 0.669 | 5.91 ± 2.15 | p = 0.513 |

| 6–10 | 21.8 ± 7.5 | 6.09 ± 2.48 | |||

| 11–20 | 21.2 ± 5.4 | 5.78 ± 1.89 | |||

| ≥21 | 20.8 ± 5.3 | 5.63 ± 1.80 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stefanowicz-Bielska, A.; Słomion, M.; Rąpała, M. Life Satisfaction of Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16789. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416789

Stefanowicz-Bielska A, Słomion M, Rąpała M. Life Satisfaction of Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16789. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416789

Chicago/Turabian StyleStefanowicz-Bielska, Anna, Magdalena Słomion, and Małgorzata Rąpała. 2022. "Life Satisfaction of Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16789. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416789

APA StyleStefanowicz-Bielska, A., Słomion, M., & Rąpała, M. (2022). Life Satisfaction of Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16789. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416789