Dissemination in Extension: Health Specialists’ Information Sources and Channels for Health Promotion Programming

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Framework

2.2. Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Survey

- Which information channels and sources are used to influence the intervention adoption-decision making process for Extension health specialists and channels used for educator communication? Which sources (e.g., journals, other specialists, etc.) and channels of communication (e.g., email, phone, face-to-face, etc.) are used most often (1—Never; 5—Most often use) to seek intervention information? Response options were informed by previous literature on Extension [5,7,8,14,31].

- Which channels communication and frequency of communication do specialists utilize with educators? Which sources (e.g., journals, other specialists, etc.) and methods of communication (e.g., email, phone, face-to-face, etc.) are used most often (1—Never; 5—Most often use) to seek intervention information? Response options were informed by information sources, channels, and previous literature on Extension [5,7,8,14,31].

- What are the specialists’ perceptions of a dissemination strategy and interest level surrounding dissemination in Extension? This question explored the demand of a dissemination strategy (e.g., How useful do you believe a dissemination (the active targeting of information delivery) intervention would be that actively distributed new evidence-based practices to you, specialists, that you could use to distribute to Extension health educators? (1 = Not at all Useful and 5 = Extremely Useful)

- Demographic variables were assessed based on standard variables in methodology literature [35,36] and previous work [37,38,39] and included race, ethnicity, sex, age, state of employment, official role title within Extension, duration of employment within Extension, and educational degree and field.

Survey Analysis

2.5. Semi-Structured Interviews

Semi-Structured Interview Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.2. Quantitative Results

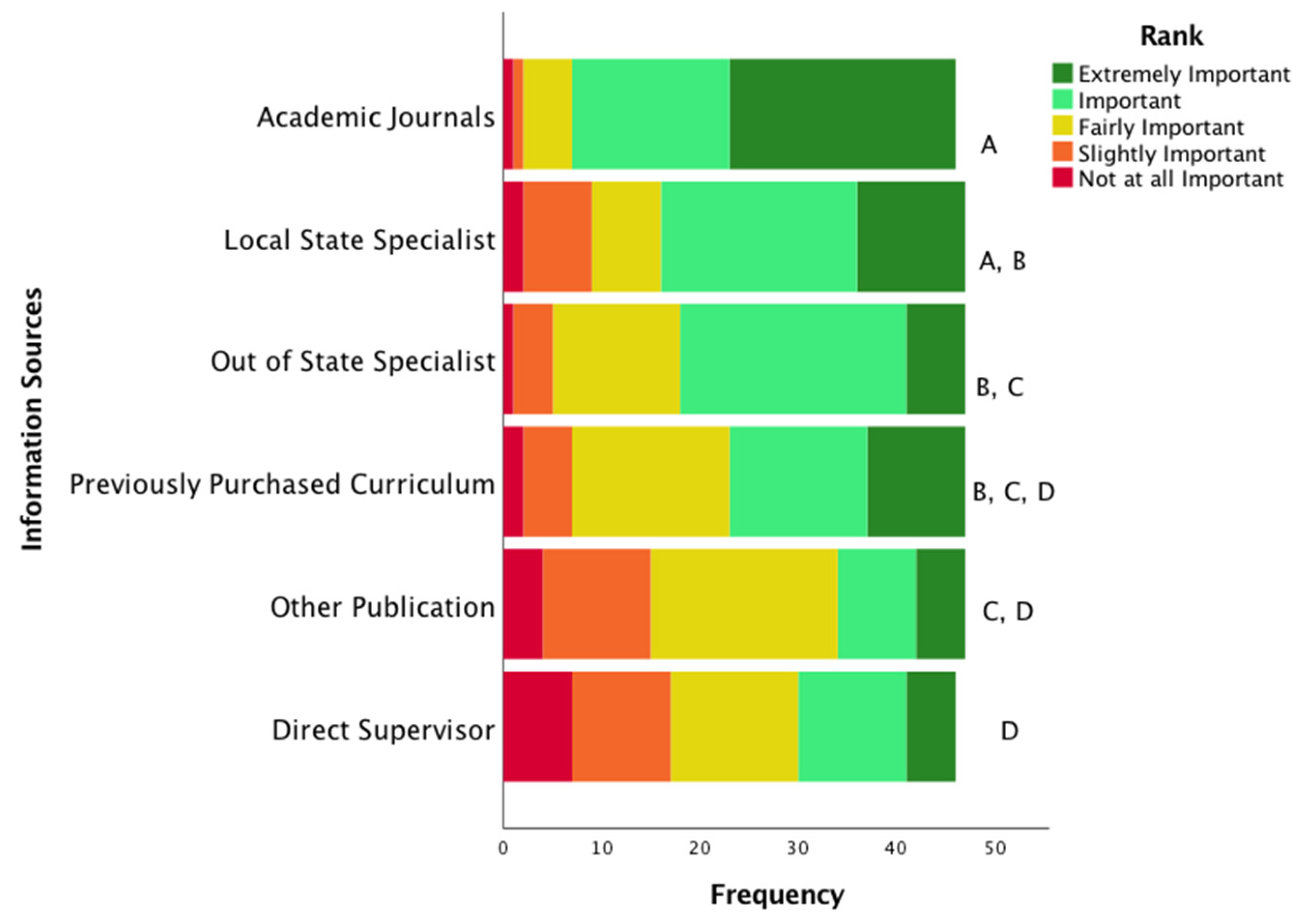

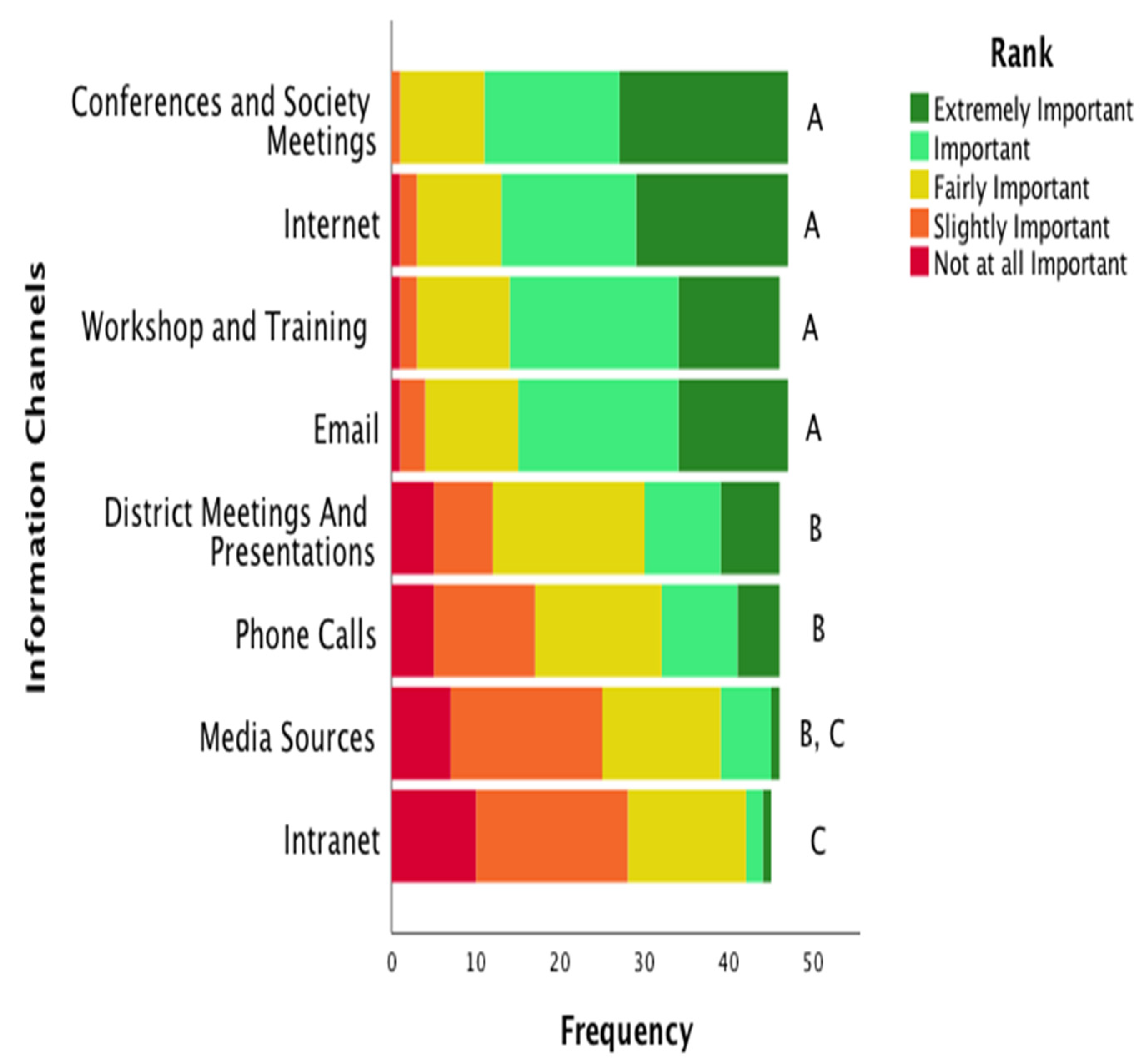

3.2.1. Specialists’ Information Sources and Channels for Programming Information

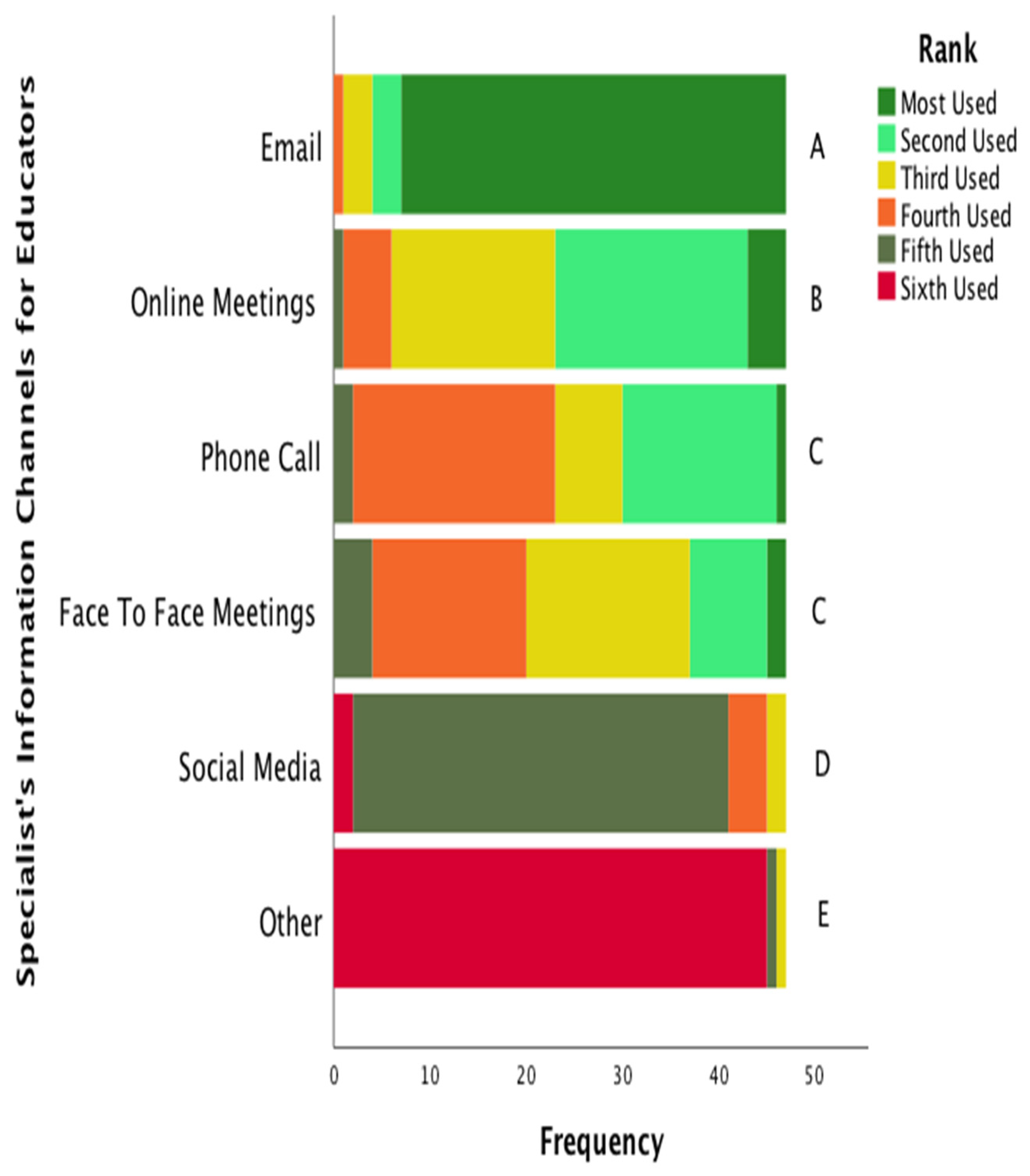

3.2.2. Specialists’ Frequency and Channels for Educator Communication

3.3. Qualitative Results

3.3.1. Specialist Information Sources and Channels

3.3.2. Specialists Communication with Educators

3.3.3. Initial Perceptions of a Dissemination Strategy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rasmussen, W.D. Taking the University to the People: Seventy-Five Years of Cooperative Extension; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Extension. Available online: https://nifa.usda.gov/extension (accessed on 1 January 2016).

- Braun, B.; Bruns, K.; Cronk, L.; Kirk Fox, L.; Koukel, S.; Le Menestrel, S.; Monroe Lord, L.; Reeves, C.; Rennekamp, R.; Rice, C.; et al. Cooperative Extension’s National Framework for Health and Wellness; Extension Committee on Organization and Policy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Battelle. 2015 Battelle Study: Analysis of the Value of Family & Consumer Sciences Extension in the North Central Region; Battelle: Columbus, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, N.; Hill, A.; Arnold, S. Information-Seeking Practices of County Extension Agents. J. Ext. 2014, 52, v52-3rb1. [Google Scholar]

- Mastel, K.L. Extending Our Reach: Surveying, Analyzing, and Planning Outreach to Extension Staff. J. Agric. Food Inf. 2014, 15, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishna, R.B.; Thomson, J.S. Extension Agents’ Use of Information Sources. J. Ext. 1996, 34, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Strayer, T.E., III; Kennedy, L.; Balis, L.; Ramalingam, N.; Wilson, M.; Harden, S. Cooperative Extension Gets Moving, but How? Exploration of Extension Health Educators’ Sources and Channels for Information-Seeking Practices. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, D.A.; Sarli, C.C.; Suiter, A.M.; Carothers, B.J.; Combs, T.B.; Allen, J.L.; Beers, C.E.; Evanoff, B.A. The Translational Science Benefits Model: A New Framework for Assessing the Health and Societal Benefits of Clinical and Translational Sciences: Translational Science Benefits Model. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2018, 11, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, S.; Washburn, L.; Berg, A.; Pena-Purcell, N.; Norman-Burgdolf, H.; Franz, N. A Brief Report on a Facilitated Approach to Connect Cooperative Extension Southern Region State-Level Health Specialists. J. Hum. Sci. Ext. 2020, 8, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balis, L.; Strayer, T.; Ramalingam, N.; Wilson, M.; Harden, S. Open-Access Physical Activity Programs for Older Adults: A Pragmatic and Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2019, 59, e268–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, S.M.; Ramalingam, N.; Breig, S.; Estabrooks, P. Walk This Way: Our Perspectives on Challenges and Opportunities for Extension Statewide Walking Promotion Programs. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarons, G.; Sklar, M.; Mustanski, B.; Benbow, N.; Hendricks Brown, C. “Scaling-out” Evidence-Based Interventions to New Populations or New Health Care Delivery Systems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownson, R.C.; Colditz, G.A.; Proctor, E.K. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-068321-4. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson, R.; Eyler, A.; Harris, J.; Moore, J.; Tabak, R. Getting the Word Out: New Approaches for Disseminating Public Health Science. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2018, 24, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehoux, P.; Denis, J.-L.; Tailliez, S.; Hivon, M. Dissemination of Health Technology Assessments: Identifying the Visions Guiding an Evolving Policy Innovation in Canada. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2005, 30, 603–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LSE Public Policy Group. Maximizing the Impacts of Your Research: A Handbook for Social Scientists; LSE Public Policy Group: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, J.; Birken, S.A.; Powell, B.J.; Rohweder, C.; Shea, C.M. Beyond “Implementation Strategies”: Classifying the Full Range of Strategies Used in Implementation Science and Practice. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damschroder, L.; Aron, D.; Keith, R.; Kirsh, S.; Alexander, J.; Lowery, J. Fostering Implementation of Health Services Research Findings into Practice: A Consolidated Framework for Advancing Implementation Science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.J.; Beidas, R.S.; Lewis, C.C.; Aarons, G.A.; McMillen, J.C.; Proctor, E.K.; Mandell, D.S. Methods to Improve the Selection and Tailoring of Implementation Strategies. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2017, 44, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.; Sequeira, S.; Jacob, R.R.; Hino, A.A.F.; Stamatakis, K.A.; Harris, J.K.; Elliott, L.; Kerner, J.F.; Jones, E.; Dobbins, M.; et al. Promoting State Health Department Evidence-Based Cancer and Chronic Disease Prevention: A Multi-Phase Dissemination Study with a Cluster Randomized Trial Component. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownson, R.C.; Ballew, P.; Brown, K.L.; Elliott, M.B.; Haire-Joshu, D.; Heath, G.W.; Kreuter, M.W. The Effect of Disseminating Evidence-Based Interventions That Promote Physical Activity to Health Departments. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 1900–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, J.M.; Langer, S.M.; Rhew, L.K.; Thomas, C. The Role of State Health Departments in Supporting Community-Based Obesity Prevention. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2011, 8, A87. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.; Beidas, R.S. Refining Contextual Inquiry to Maximize Generalizability and Accelerate the Implementation Process. Implement. Res. Pract. 2021, 2, 263348952199494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Siegel, J.; Becker-Haimes, E.M.; Jager-Hyman, S.; Beidas, R.S.; Young, J.F.; Wislocki, K.; Futterer, A.; Mautone, J.A.; Buttenheim, A.M.; et al. Identifying Common and Unique Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing Evidence-Based Practices for Suicide Prevention across Primary Care and Specialty Mental Health Settings. Arch. Suicide Res. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, R.; Khoong, E.C.; Chambers, D.A.; Brownson, R. Bridging Research and Practice Models for Dissemination and Implementation Research. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, B. Dissemination & Implementation Models in Health Research and Practice. Available online: https://dissemination-implementation.org/viewAll_di.aspx (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Holt, C.L.; Chambers, D.A. Opportunities and Challenges in Conducting Community-Engaged Dissemination/Implementation Research. Behav. Med. Pract. Policy Res. 2017, 7, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Hagedorn, H.J. A Guiding Framework and Approach for Implementation Research in Substance Use Disorders Treatment. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2011, 25, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4516-0247-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Maheshwari, B.; Kumar, U. Enterprise Resource Planning Systems Adoption Process: A Survey of Canadian Organizations. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2002, 40, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Plano Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, F.G.; Kellison, J.G.; Boyd, S.J.; Kopak, A. A Methodology for Conducting Integrative Mixed Methods Research and Data Analyses. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2010, 4, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, S.; Gunter, K.; Lindsay, A. How to Leverage Your State’s Land Grant Extension System: Partnering to Promote Physical Activity. Transl. J. Am. Coll. Sport. Med. 2018, 3, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Phrommathed, P. Research Methodology. In New Product Development; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Orcher, L. Conducting Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-351-97066-2. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, S.; Wages, J.; Jackson, S.F.; Estabrooks, P.A. Adoption Decisions and Implementation of a Community-Based Physical Activity Program: A Mixed Methods Study. Health Promot. Pract. 2012, 13, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, S.; Gaglio, B.; Shoup, J.; Kinney, K.; Johnson, S.; Brito, F.; Blackman, K.; Zoellner, J.; Hill, J.; Almeida, F.; et al. Fidelity to and Comparative Results across Behavioral Interventions Evaluated through the RE-AIM Framework: A Systematic Review. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoellner, J.; Krzeski, E.; Harden, S.; Cook, E.; Allen, K.; Estabrooks, P.A. Qualitative Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Beverage Consumption Behaviors among Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1774–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino, A.R. Analyzing and Interpreting Data From Likert-Type Scales. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Generalization in Quantitative and Qualitative Research: Myths and Strategies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkan, J. Immersion/Crystallization. In Doing Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes, A.C.; Smith, B. Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health. Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-136-97472-4. [Google Scholar]

- Strayer III, T.E.; Balis, L.E.; Kennedy, L.E.; Ramalingam, N.S.; Wilson, M.L.; Harden, S.M. Intervention Characteristics Considered in Health Educators’ Adoption-Decision Making Process. Health Educ. Behav. 2022, 10901981211067170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensle, K.M. Burnout: How Does Extension Balance Job and Family? J. Ext. 2005, 43, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kutilek, L.M.; Conklin, N.L.; Gunderson, G. Investing in the Future: Addressing Work/Life Issues of Employees. J. Ext. 2002, 40, n1. [Google Scholar]

- Harden, S.; Steketee, A.; Glasgow, T.; Glasgow, R.; Estabrooks, P. Suggestions for Advancing Pragmatic Solutions for Dissemination: Potential Updates to Evidence-Based Repositories. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 35, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhardt, J.T.; Schröter, D.C.; Magura, S.; Means, S.N.; Coryn, C.L.S. An Overview of Evidence-Based Program Registers (EBPRs) for Behavioral Health. Eval. Program Plan. 2015, 48, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, L.E.; Strayer, T.E.I.; Balis, L.E. Addressing Health Inequities: An Exploratory Assessment of Extension Educators’ Perceptions of Program Demand for Diverse Communities. Fam. Community Health 2022, 45, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balis, L.E.; Strayer, T.E.; Ramalingam, N.; Harden, S.M. Beginning with the End in Mind: Contextual Considerations for Scaling-Out a Community-Based Intervention. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, S.; Balis, L.; Strayer, T.; Carlson, B.; Lindsay, A.; Dzewaltowski, D.; Estabrooks, P.; Gunter, K. Strengths, Challenges, and Opportunities for Physical Activity Promotion in the Century-Old National Cooperative Extension System. J. Hum. Sci. Ext. 2020, 8, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Balis, L.E.; Gallup, S.; Norman-Burgdolf, H.; Buck, J.; Daniels, P.; Remley, D.; Graves, L.; Jenkins, M.; Price, M. Unifying Multi-State Efforts Through a Nationally Coordinated Extension Diabetes Program. J. Hum. Sci. Ext. 2022, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics Variable | Survey Respondents (N = 47) | Interview Respondents (N = 10) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male n (%) | 4 (9) | 2 (20) |

| Female n (%) | 42 (89) | 8 (80) |

| Other n (%) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Age Mean (STD) | 46.9 (±13.4) | 40.1 (±12.9) |

| Spanish, Hispanic, or Latino | ||

| Yes | 3 (7) | 0 (0) |

| No | 44 (93) | 9 (90) |

| Race | ||

| White or Caucasian | 33 (70) | 10 (100) |

| Black or African American | 7 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 5 (11) | 0 (0) |

| Percentage of time spent (Mean Percent) (STD) | ||

| Research | 21 (±19) | 23 (±20) |

| Extension | 68 (±30) | 68 (±31) |

| Teaching | 19 (±15) | 21 (±15) |

| Duration as a Specialist in Cooperative Extension Mean (STD) | 10.19 (9.69) years | 7.86 (±9.5) |

| Highest level of Education n (%) | ||

| Master’s degree (course option) | 11 (23) | 3 (30) |

| Master’s degree (Thesis Option) | 6 (13) | 1 (10) |

| Doctorate degree | 29 (62) | 6 (60) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme (n = Number of Specialists Contributing Meaning Units) | Sub-Theme Descriptions (n = Number of Specialists Contributing Meaning Units) |

|---|---|---|

| Specialist Information Sources and Channels | Academic Journals (10) | Frequency: Use as needed (8) Information Channel: Internet (website/google scholar) (2) Direction of Dissemination: Bi-directional (8) Perceptions: Trustworthy source of information (9), For evidence-based information, not programming-specific (8), Journals [17 mentioned] (8) Suggestions for Improvement: More details in intervention methodology (1), Prefer journal article be supplemental to intervention information (1) |

| Specialist (10) | Frequency: Use as needed (6), Rarely or infrequent (2) Information Channel: Conferences (7), Meetings (6), Email (3), Phone calls (2) Direction of Dissemination: Bi-directional (3), Actively reaches out (1) Perceptions: Use in-state specialist (6), Use out-of-state specialist (6), Trustworthy source of information (8), Not a trustworthy source of information (1), Good information source for programming information (6) Suggestions for Improvement: Programming can be costly coming from other specialist (1), Specialist should be more uniform in qualifications (1) | |

| Government Organizations (10) | Frequency: Use as needed (10) Information Channel: Internet (websites or online repositories) (10) Direction of Dissemination: Bi-directional (5) Perceptions: Use a variety of sources such as: CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] (7), Extension (8), USDA [United States Department of Agriculture] (4), eXtension (3), NIH [National Institutes of Health] (3), Federal Trade Commission (1), Public Health Department (1), Center TRT [Training and Research Translation] (1), Use trustworthy sources of Information (8), Non-branded resource (2) Suggestions for Improvement: Programming can be costly coming from other specialist (1), Specialist should be more uniform in qualifications (1) | |

| Non-Profit Organizations (3) | Perceptions: American Diabetes Association (2), American Heart Association (2), Dairy Council (1) | |

| Private Organizations (1) | Perceptions: Gatorade Sports Science Institute (1) | |

| Specialist Communication with Educators | Email (10) | Content: Emails contain information on community needs or addressing community needs (10) Frequency: Daily-weekly (10), Listserv (as needed or scheduled updates) (7) Direction of dissemination: Bi-directional (10) Rationale: Most common channel to communicate with multiple educators (7) |

| Training (8) | Content: Extension-approved programming for delivery (8) Dose: Intervention dependent (8) Information channel:

Rationale: Specialist believe that training improves program adoption and fidelity (1), Needs a funding mechanism (1) | |

| Web-based Tool (WebEx/Zoom/Dropbox) (5) | Content: Statewide initiative information/health topics in communities/intervention information (4) Frequency: Monthly and based on health topics and intervention needs (4) Direction of dissemination: Specialist to educator (5) Rationale: Educators requested this channel of communication as it is convenient and easier to facilitate statewide meetings (3) | |

| Social Media (5) | Rationale: Specialists often state that social media was not a tool to be used to communicate with educators (5) | |

| Additional Communication Information(Unique Insight provided by Specialist) (5) |

| |

| Phone (3) | Content: Community need and intervention information (3) Frequency: Episodic (1), as needed (2) Direction of dissemination: Bi-directional (3) Rationale: Informal means of communication (1), Can use conference calls for multiple individuals, specialist also believes talking improves personal relationships increasing intervention success (2) | |

| Dissemination Strategy | Specialists (10) | Dissemination Content: Intervention-specific information (9), Extension intervention information (7) Frequency: As needed for intervention information, updates, etc. (5), Monthly (1), Quarterly (2), Systematic approach to dissemination (1) Information Channel: Email (8), online programming repository (2), Phone (1), Webinar (1) Direction of Dissemination: Specialist to educators (9), Specialist to specialist then to educators (3) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strayer, T.E., III; Balis, L.E.; Ramalingam, N.S.; Harden, S.M. Dissemination in Extension: Health Specialists’ Information Sources and Channels for Health Promotion Programming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416673

Strayer TE III, Balis LE, Ramalingam NS, Harden SM. Dissemination in Extension: Health Specialists’ Information Sources and Channels for Health Promotion Programming. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416673

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrayer, Thomas E., III, Laura E. Balis, NithyaPriya S. Ramalingam, and Samantha M. Harden. 2022. "Dissemination in Extension: Health Specialists’ Information Sources and Channels for Health Promotion Programming" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416673

APA StyleStrayer, T. E., III, Balis, L. E., Ramalingam, N. S., & Harden, S. M. (2022). Dissemination in Extension: Health Specialists’ Information Sources and Channels for Health Promotion Programming. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416673