Discrimination against and Associated Stigma Experienced by Transgender Women with Intersectional Identities in Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection and Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Discrimination at an Educational Institution

3.3. Discrimination in the Workplace

3.4. Discrimination in Daily Life

3.5. Discrimination at a Healthcare Facility

3.6. The Effects of Intersectional Identities on Discrimination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNDP. Tolerance but Not Inclusion: A National Survey on Experiences of Discrimination and Social Attitudes towards LGBT People in Thailand; UNDP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Suriyasarn, B. Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation in Thailand; International Labour Organization: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pravattiyagul, J. Thai transgender women in Europe: Migration, gender and binational relationships. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2021, 30, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, J.W. Thailand Migration Report 2014; United Nations Thematic Working Group on Migration in Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Villar, L.B. Unacceptable Forms of Work in the Thai Sex and Entertainment Industry. Anti-Traffick. Rev. 2019, 12, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, S.L.; Adelson, J.L.; Howard, K.A. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizock, L.; Mueser, K.T. Employment, mental health, internalized stigma, and coping with transphobia among transgender individuals. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2014, 1, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.E.; Herman, J.L.; Rankin, S.; Keisling, M.; Mottet, L.; Anafi, M. Executive Summary of the Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey; National Center for Transgender Equality: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, M.N.; Kanouse, D.E.; Burkhart, Q.; Abel, G.A.; Lyratzopoulos, G.; Beckett, M.K.; Schuster, M.A.; Roland, M. Sexual Minorities in England Have Poorer Health and Worse Health Care Experiences: A National Survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 30, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Hughto, J.M.; Reisner, S.L.; Pachankis, J.E. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.K.; Thorn, B.E. Intersectional identity approach to chronic pain disparities using latent class analysis. Pain 2022, 163, e547–e556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolding, P. Intersectionality vs. Intersecting Identities. Available online: https://www.oregon.gov/deiconference/Documents/Pharoah%20Bolding%20-%20Intersectionality%20vs.%20Intersecting%20Identities.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Grollman, E.A. Multiple disadvantaged statuses and health: The role of multiple forms of discrimination. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2014, 55, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.R. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pedro, K.T.; Shim-Pelayo, H.; Bishop, C. Exploring Physical, Nonphysical, and Discrimination-Based Victimization among Transgender Youth in California Public Schools. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2019, 1, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP; ILO. LGBTI People and Employment: Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression, and Sex Characteristics in China, the Philippines and Thailand; United Nations Development Programme: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Day, J.K.; Perez-Brumer, A.; Russell, S.T. Safe Schools? Transgender Youth’s School Experiences and Perceptions of School Climate. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1731–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhedchawanagon, K. Situation Sexual Stigma Among Transgender Students in Chiangmai. J. Integr. Sci. 2020, 17, 12–39. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Economic Inclusion of LGBTI Groups in Thailand in 2018; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, B.; Mallory, C.; Flores, A.R.; Conron, K.J. LGBT People’s Experiences of Workplace Discrimination and Harassment. Available online: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/lgbt-workplace-discrimination/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- UNDP. Stories of Stigma: Exploring Stigma and Discrimination against Thai Transgender People while Accessing Health Care and in Other Settings; UNDP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ojanen, T.T.; Burford, J.; Juntrasook, A.; Kongsup, A.; Assatarakul, T.; Chaiyajit, N. Intersections of LGBTI Exclusion and Discrimination in Thailand: The Role of Socio-Economic Status. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2019, 16, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, D.W.; Taylor, N.; Signal, T.; Fraser, H.; Donovan, C. People of Diverse Genders and/or Sexualities and Their Animal Companions: Experiences of Family Violence in a Binational Sample. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 4226–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, E.L.; Wilchins, R.A.; Priesing, D.; Malouf, D. Gender Violence. J. Homosex. 2002, 42, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. World Report 2021 Events of 2020; HRW: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- USAID. Being LGBT in Asia: Thailand Country Report; United Nations Development Programme: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014.

- Chladek, M.R. Defining Manhood: Monastic Masculinity and Effeminacy in Contemporary Thai Buddhism. J. Asian Stud. 2021, 80, 975–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käng, D.B.c. Kathoey “In Trend”: Emergent Genderscapes, National Anxieties and the Re-Signification of Male-Bodied Effeminacy in Thailand. Asian Stud. Rev. 2012, 36, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddhisaro, P.R.; Sakaew, A. Theravada Buddhism: Gender’s Right and Ordination in Thai Society. ASEAN J. Relig. Cult. Res. 2018, 1, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, J.; Reisner, S.L.; Honnold, J.A.; Xavier, J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1820–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteat, T.; German, D.; Kerrigan, D. Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 84, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzer, C.; LaGata, C.; Hutta, J.S.; TGEU. Transrespect Versus Transphobia Worldwide: The Social Experiences of Trans and Gender-Diverse People in Colombia, India, the Philippines, Serbia, Thailand, Tonga, Turkey and Venezuela; TGEU: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bristowe, K.; Hodson, M.; Wee, B.; Almack, K.; Johnson, K.; Daveson, B.A.; Koffman, J.; McEnhill, L.; Harding, R. Recommendations to reduce inequalities for LGBT people facing advanced illness: ACCESSCare national qualitative interview study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.C.; Arayasirikul, S.; Johnson, K. Access to HIV Care and Support Services for African American Transwomen Living with HIV. Int. J. Transgend. 2013, 14, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.Y.; Baig, A.A.; Chin, M.H. High Stakes for the Health of Sexual and Gender Minority Patients of Color. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 1390–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brondolo, E.; Kelly, K.P.; Coakley, V.; Gordon, T.; Thompson, S.; Levy, E.; Cassells, A.; Tobin, J.N.; Sweeney, M.; Contrada, R.J. The Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire: Development and Preliminary Validation of a Community Version1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 335–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, J.; Atencio, J.; Ullah, J.; Crupi, R.; Chen, D.; Roth, A.R.; Chaplin, W.; Brondolo, E. The Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire—Community Version: Validation in a multiethnic Asian sample. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2011, 17, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Arayasirikul, S.; Raymond, H.F.; McFarland, W. The Impact of Discrimination on the Mental Health of Trans*Female Youth and the Protective Effect of Parental Support. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 2203–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, C. Gender minority stress in education: Protecting trans children’s mental health in UK schools. Int. J. Transgender Health 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price-Feeney, M.; Green, A.E.; Dorison, S. Understanding the Mental Health of Transgender and Nonbinary Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.T.; Pollitt, A.M.; Li, G.; Grossman, A.H. Chosen Name Use Is Linked to Reduced Depressive Symptoms, Suicidal Ideation, and Suicidal Behavior Among Transgender Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price-Feeney, M.; Green, A.E.; Dorison, S.H. Impact of Bathroom Discrimination on Mental Health Among Transgender and Nonbinary Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, L.B. Sisters, Boyfriends, and the Big City: Trans Entertainers and Sex Workers in Globalized Thailand. Master’s Thesis, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Napatanapong, C.; Saowakhon, R. Thailand Should Legalise Prostitution. Available online: https://tdri.or.th/en/2022/07/thailand-should-legalise-prostitution/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Chokrungvaranont, P.; Selvaggi, G.; Jindarak, S.; Angspatt, A.; Pungrasmi, P.; Suwajo, P.; Tiewtranon, P. The development of sex reassignment surgery in Thailand: A social perspective. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 182981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Rights Watch. People Can’t Be Fit into Boxes Thailand’s Need for Legal Gender Recognition; Human Rights Watch: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The American National Red Cross. LGBTQ + Donors. Available online: https://www.redcrossblood.org/donate-blood/how-to-donate/eligibility-requirements/lgbtq-donors.html (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Australian Red Cross Lifeblood. Available online: https://www.lifeblood.com.au/blood/eligibility/sexual-activity (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Cyrus, K. Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ people of color. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2017, 21, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | ||

| Median of age (interquartile range) | 30 (28–40) | |

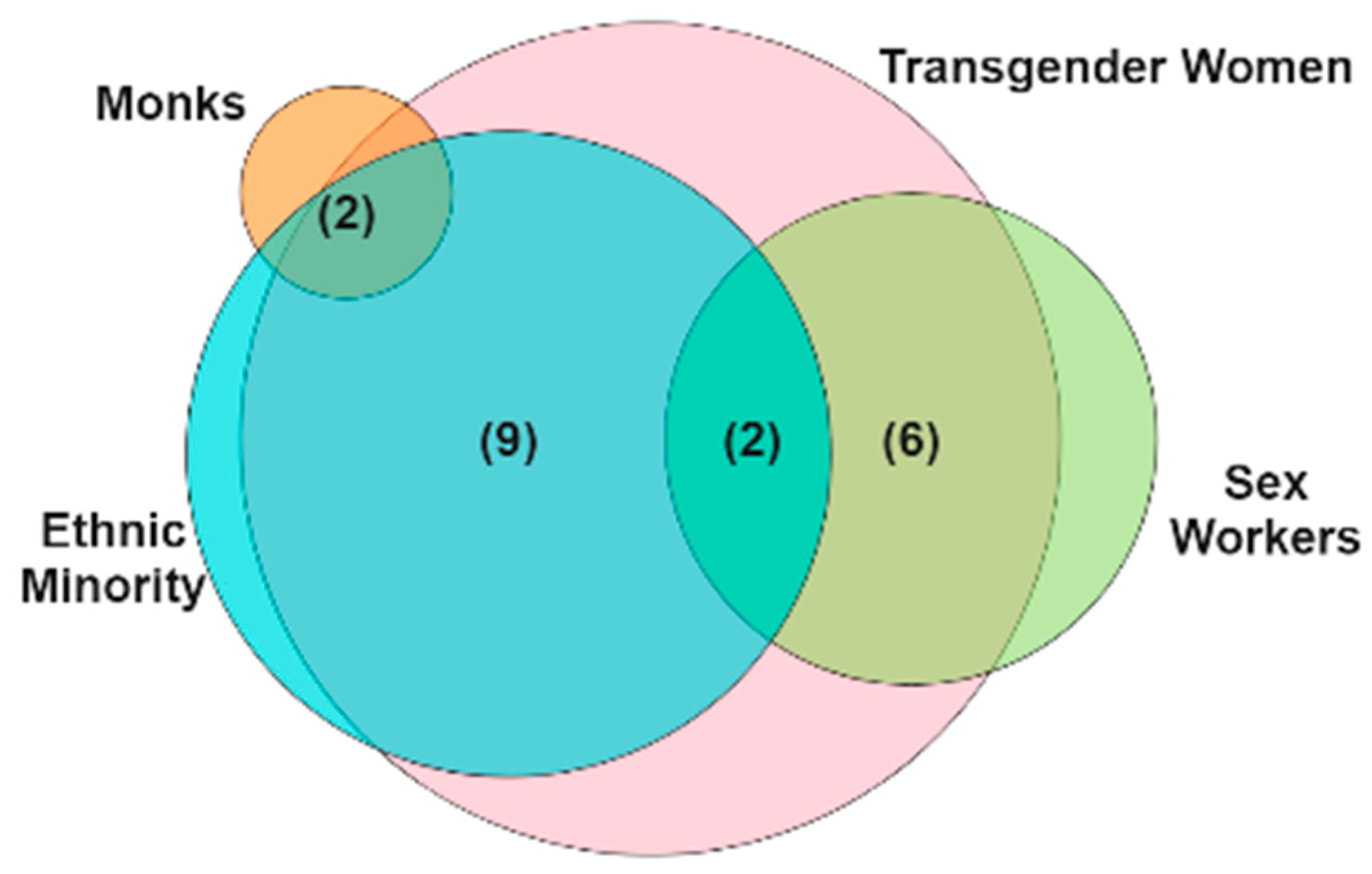

| Intersectional nature | ||

| Ethnic minority TGW | 9 | 47.0 |

| TGW freelancer | 6 | 31.0 |

| Ethnic minority TGW freelancer | 2 | 11.0 |

| Ethnic minority TGW monk | 2 | 11.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Tai Yong | 4 | 21.0 |

| Tai Lue | 1 | 5.0 |

| Tai Yai | 8 | 42.0 |

| Thai | 6 | 32.0 |

| Status | ||

| Single/widowed | 8 | 42.0 |

| Married/have a boyfriend or girlfriend | 3 | 16.0 |

| Not specified | 8 | 42.0 |

| Education level | ||

| Uneducated/primary school | 4 | 21.0 |

| Secondary school/vocational certificate | 10 | 53.0 |

| Higher vocational certificate/bachelor’s degree/postgraduate | 5 | 26.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Government employee/private business owner | 7 | 36.0 |

| Monk | 2 | 11.0 |

| Freelancer | 8 | 42.0 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 11.0 |

| Sex worker status | ||

| Yes | 8 | 42.0 |

| No | 11 | 58.0 |

| Length of stay in Thailand | ||

| Since birth | 6 | 32.0 |

| 1–10 years | 1 | 5.0 |

| ≥11 years | 7 | 36.0 |

| Not specified | 5 | 27.0 |

| ID | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | Type of Discrimination | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 16 | 19 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 6 | 12 | 8 | 9 |

| Workplace | Physical harm, being disparaged | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

| Refusal of employment | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Harsh words | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

| Educational Institution | Hash words | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| Physical violence | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||

| Impact on learning | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Healthcare | Humiliation | √ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Discrimination and stigma | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Restriction of rights | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||

| Daily life | Restriction of rights | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||

| Being rejected by family and local people | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| Sexual harassment | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Verbal bullying | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| Number of discrimination forms | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| Number of intersectional identities | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Intersectional identity categories | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | ||||||||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Srikummoon, P.; Thanutan, Y.; Manojai, N.; Prasitwattanaseree, S.; Boonyapisomparn, N.; Kummaraka, U.; Pateekhum, C.; Chiawkhun, P.; Owatsakul, C.; Maneeton, B.; et al. Discrimination against and Associated Stigma Experienced by Transgender Women with Intersectional Identities in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416532

Srikummoon P, Thanutan Y, Manojai N, Prasitwattanaseree S, Boonyapisomparn N, Kummaraka U, Pateekhum C, Chiawkhun P, Owatsakul C, Maneeton B, et al. Discrimination against and Associated Stigma Experienced by Transgender Women with Intersectional Identities in Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(24):16532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416532

Chicago/Turabian StyleSrikummoon, Pimwarat, Yuphayong Thanutan, Natthaporn Manojai, Sukon Prasitwattanaseree, Nachale Boonyapisomparn, Unyamanee Kummaraka, Chanapat Pateekhum, Phisanu Chiawkhun, Chayut Owatsakul, Benchalak Maneeton, and et al. 2022. "Discrimination against and Associated Stigma Experienced by Transgender Women with Intersectional Identities in Thailand" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24: 16532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416532

APA StyleSrikummoon, P., Thanutan, Y., Manojai, N., Prasitwattanaseree, S., Boonyapisomparn, N., Kummaraka, U., Pateekhum, C., Chiawkhun, P., Owatsakul, C., Maneeton, B., Maneeton, N., Kawilapat, S., & Traisathit, P. (2022). Discrimination against and Associated Stigma Experienced by Transgender Women with Intersectional Identities in Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416532