Case Study Demonstration of the Potential Acceptability and Effectiveness of a Novel Telehealth Treatment for People Experiencing Gambling Harm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Case 1

2.2.2. Case 2

2.2.3. Case 3

2.2.4. Case 4

2.3. Measures

2.4. Treatment

2.4.1. Approach

2.4.2. Engagement

2.4.3. Graded Exposure Program

- Black and white and then colour pictures of online gambling sites and sports/racing events, made increasingly difficult as the client progressed through the hierarchy.

- Studying the races or sports games, anticipating which bet would be placed without placing a bet.

- Watching a sports game/horse race turning off the sport before the end without finding out the result.

- Picking the winning sports team or horse and watching the event, and then turning off the sport before the end without finding out the winner.

2.4.4. Relapse Prevention

3. Results

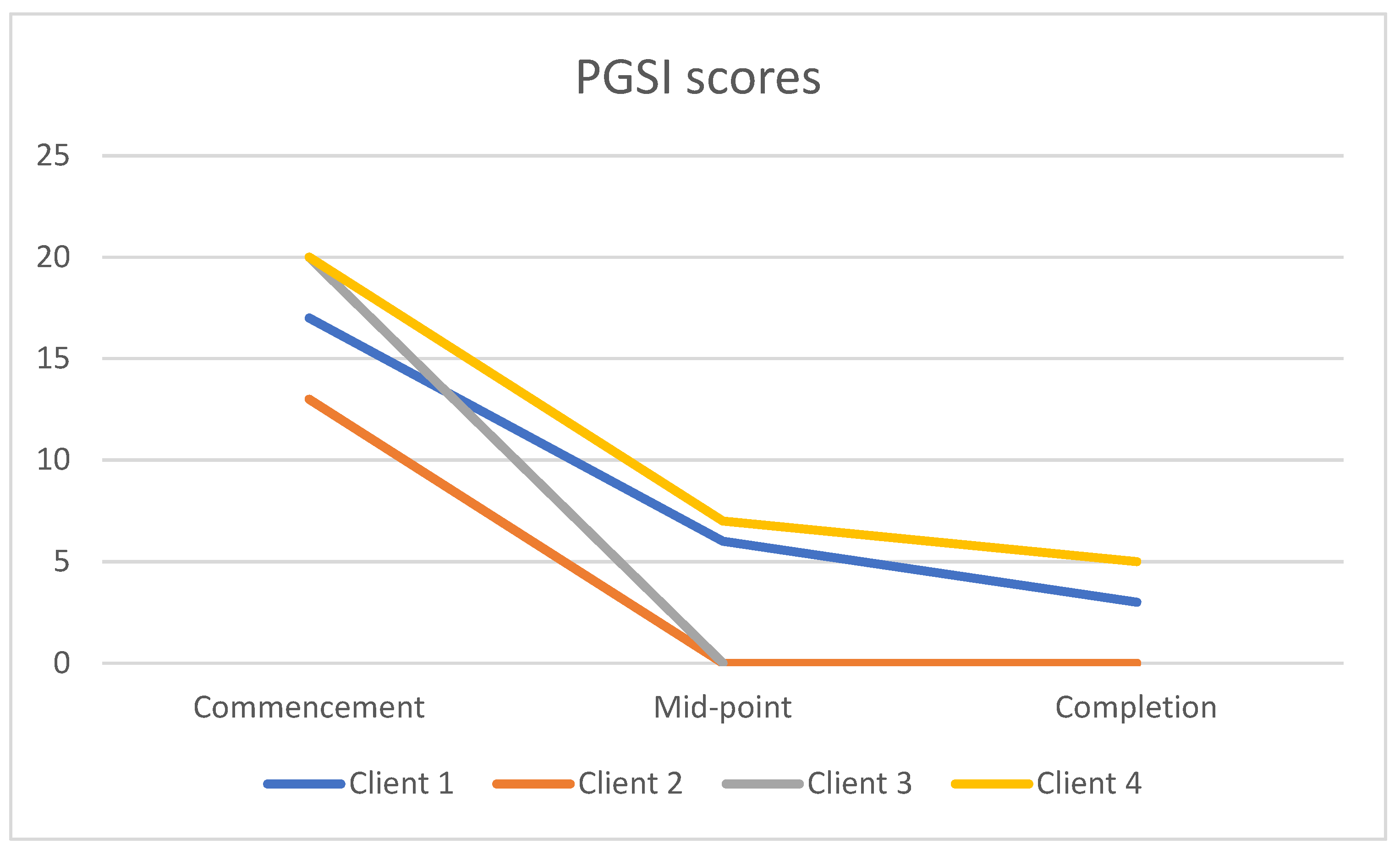

3.1. PGSI Scores

3.2. Outcome Rating Scale (ORS) Scores

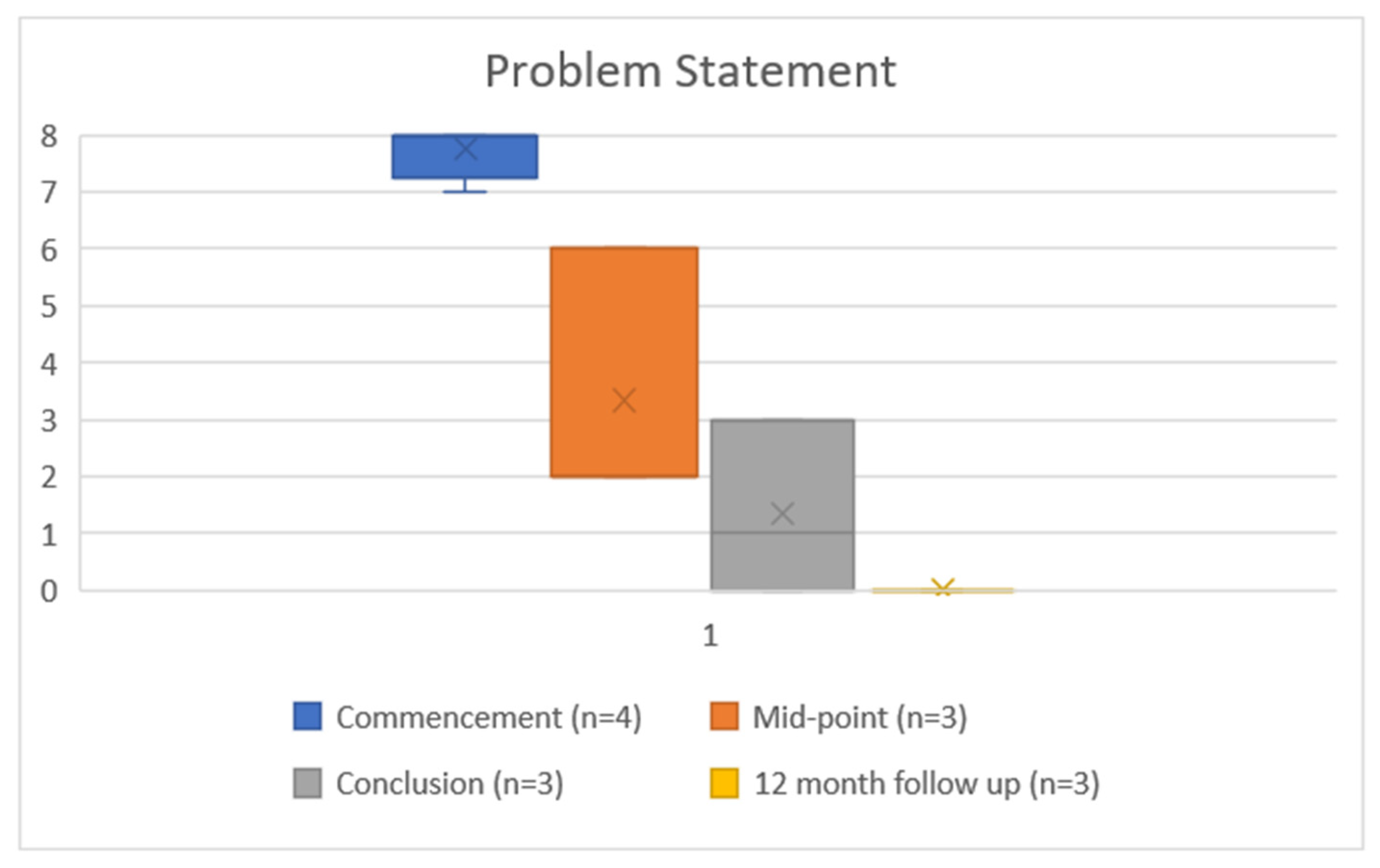

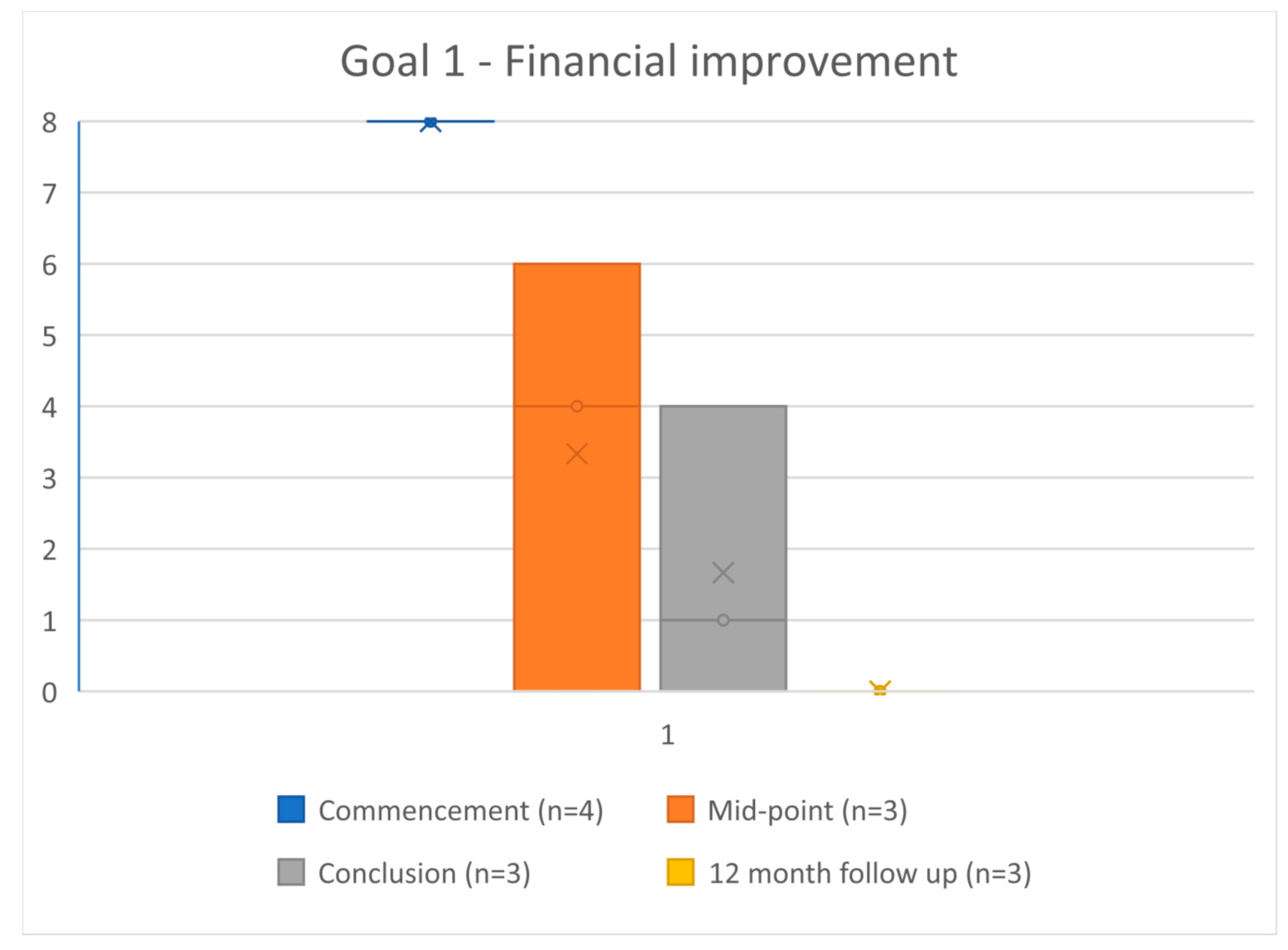

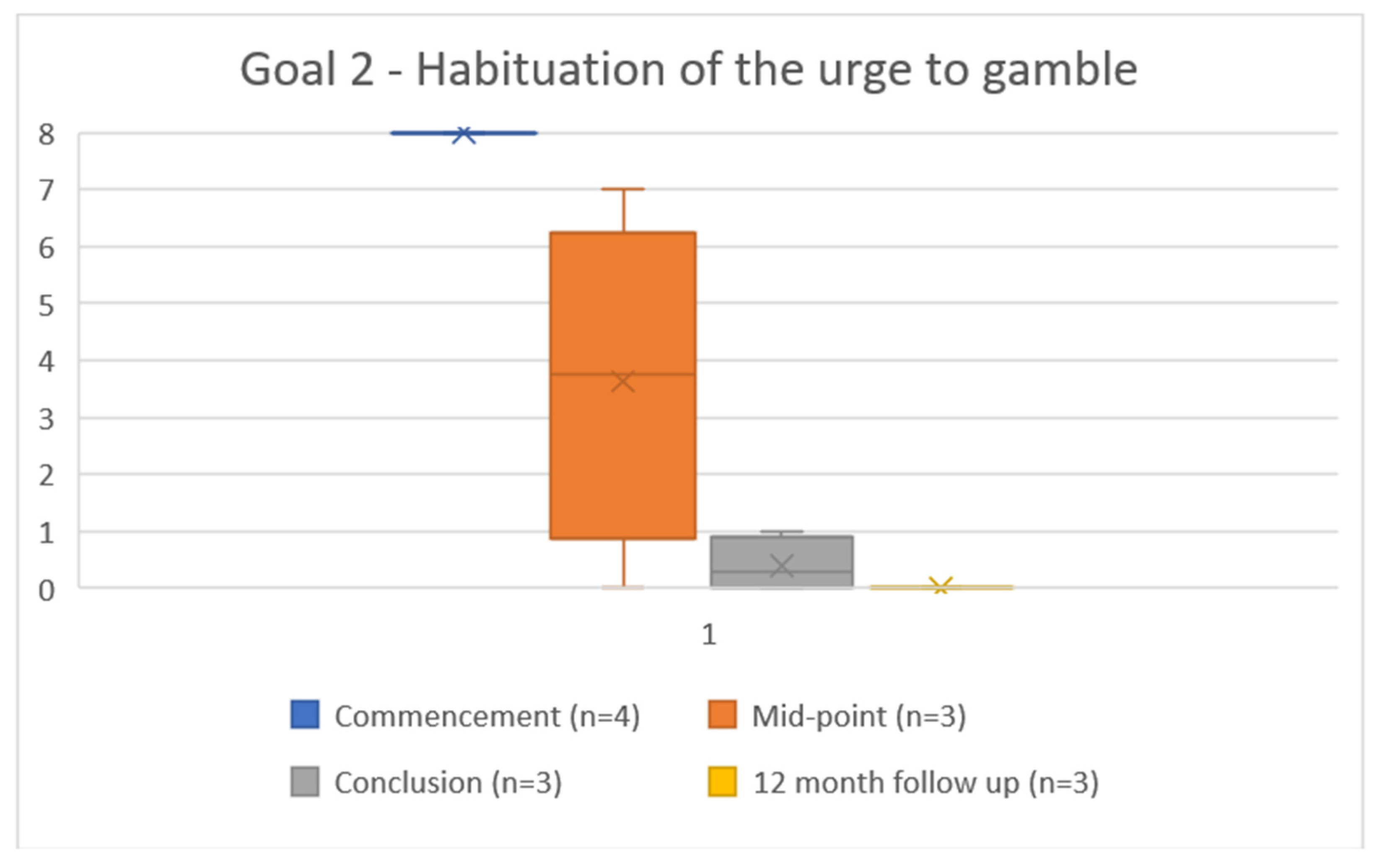

3.3. Problems and Goals Scores

3.4. Qualitative Feedback

At the start it was tricky, you’re getting to know the other guys and whatnot and we’re coming from very different backgrounds but yeah it certainly worked really well for me.(Case 3)

The shared experiences that we’ve had even though we didn’t know each other previously, so I guess, previously I’ve thought that it was just me. That no one else could be feeling like what I’m going through. So that’s one part of it and I guess helping the other guys as well. It seemed to help, you know, that we could all talk about it without judgement.(Case 2)

Obviously, we talked about it, but the fact it was by video link, because it had to be because of covid, probably been a blessing in disguise because you didn’t have that sort of confrontational element of sitting in front of other patients I suppose. Which would have been ok in time I suppose but especially in the first few weeks it was nice to know that you were still in the safety and sanctity of your own home. And obviously you’re still sharing sensitive information, but it just seemed to work. Whether it was the dynamic of the group, but that platform worked well for everyone.(Case 3)

That (videoconferencing) is probably more the winner as well because if you tell me to go to the hospital and do it there, or somewhere... but once you do it in the comfort of your own home or your car or wherever, you know, you get a little bit scared the first few times but doing it on my computer was a lot easier.(Case 1)

Oh, to be honest, it was probably my lifesaver. Whatever was offered to me I was going to take because I knew it was going to take a substantial effort from me but also the right resource to fix me long-term. So, when I started liaising with [the clinicians] and they offered me this program I just jumped at it. It was the best thing that could have happened to me. I think the biggest thing is the belief because I just had no belief that I could fix my gambling, and financially you just get to the point where think “Oh well financially, it doesn’t matter what happens, I’m not going to be able to jump over this”. But it’s just one foot in front of the other and it’s literally been a saving grace and allowed me to do things.(Case 3)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armstrong, A.; Carroll, M. Gambling Activity in Australia; Australian Gambling Research Centre, Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.; Greer, N.; Armstrong, T.; Doran, C.; Kinchin, I.; Langham, E.; Rockloff, M. The Social Cost of Gambling to Victoria; Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lubman, D.; Manning, V.; Dowling, N.; Rodda, S.; Lee, S.; Garde, E.; Merkouris, S.; Volberg, R. Problem Gambling in People Seeking Treatment for Mental Illness 2017, Report Produced by VRGF. Available online: https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/documents/61/research-report-problem-gambling-in-people-seeking-treatment-for-mental-illnes_XkVmN62.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Karlsson, A.; Hakansson, A. Gambling disorder, increased mortality, suicidality, and associated comorbidity: A longitudinal nationwide register study. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompili, M.; Innamorati, M.; Szanto, K.; Di Vittorio, C.; Conwell, Y.; Lester, D.; Tatarelli, R.; Girardi, P.; Amore, M. Life events as precipitants of suicide attempts among first-time suicide attempters, repeaters, and non-attempters. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 186, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, E.C.; Barraclough, B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 1997, 170, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.D. Suicidality in clinical practice: Anxieties and answers. J. Clin. Psych. 2006, 62, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castella, A.; Bolding, P.; Lee, A.; Cosic, S.; Kulkarni, J. Problem Gambling in People Presenting to a Public Mental Health Service; Office of Gaming and Racing, Department of Justice: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2011. Available online: https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/documents/91/Research-report-gambling-in-people-presenting-mental-health-service.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Gambling in Australia. 2021. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/gambling (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021b) COVID-19: Looking Back on Health in 2020. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/australias-health-performance/covid-19-and-looking-back-on-health-in-2020 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Simpson, S.G.; Reid, C.L. Therapeutic alliance in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A review. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2014, 22, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainsbury, S.; Blaszczynski, A. Online self-guided interventions for the treatment of problem gambling. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2011, 11, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Method 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K. Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001, 358, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, H. Introducing the Canadian Problem Gambling Index; Wynne Resources: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.; Duncan, B.; Brown, J.; Sparks, J.; Claud, D. The Outcome Rating Scale: A Preliminary Study of the Reliability, Validity, and Feasibility of a Brief Visual Analog Measure. J. Brief Ther. 2003, 2, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.; Duncan, B.; Brown, J.; Sorrell, R.; Chalk, M. Using Formal Client Feedback to Improve Retention and Outcome: Making Ongoing, Real-time Assessment Feasible. J. Brief Ther. 2006, 5, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Battersby, M.; Ask, A.; Reece, M.; Markwick, M.; Collins, J.P. A case study using the “problems and goals approach” in a coordinated care trial: SA health plus. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2001, 7, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battersby, M.; Oakes, J.; Redpath, P.; Harris, S.; Riley, B. Graded Exposure Therapy. A Treatment Manual for People with Gambling Problems; Flinders Human Behaviour and Health Research Unit: Adelaide, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Battersby, M.; Oakes, J.; Tolchard, B.; Forbes, A.; Pols, R. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Problem Gamblers, in Zangeneh, M. In the Pursuit of Winning. Problem Gambling Theory, Research and Treatment; Blaszczynski, A., Turner, N., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes, J.; Battersby, M.; Pols, R.; Cromarty, P. Exposure Therapy for Problem Gambling via Videoconferencing: A Case Report. J. Gambl. Stud. 2008, 24, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.P.; Battersby, M.W.; Pols, R.G.; Harvey, P.W.; Oakes, J.E.; Baigent, M.F. Predictors of relapse in problem gambling: A prospective cohort study. J. Gambl. Stud. 2015, 31, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakes, J.; Pols, R.; Battersby, M.; Lawn, S.; Pulvirenti, M.; Smith, D. A Focus Group Study of Predictors of Relapse in Electronic Gaming Machine Problem Gambling, Part 1: Factors that ‘Push’ Towards Relapse. J. Gambl. Stud. 2012, 28, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliuc, A.M.; Doan, T.N.; Best, D. Sober social networks: The role of online support groups in recovery from alcohol addiction. J. Community App. Soc. Psych. 2018, 29, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvain, C.; Ladouceur, R.; Boisvert, J.-M. Cognitive and behavioral treatment of pathological gambling: A controlled study. J. Consult. Clin. Psych. 1997, 65, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, B.J.; Harris, S.; Nye, T.; Javidi-Hosseinabad, Z.; Baigent, M. Graded exposure therapy for online mobile smartphone sports betting addiction: A case series report. J. Gambl. Stud. 2021, 37, 1263–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, J.; Wynne, H. The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final Report; Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/(S(351jmbntvnsjt1aadkposzje))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=170183 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Browne, M.; Langham, E.; Rawat, V.; Greer, N.; Li, E.; Rose, J.; Rockloff, M.; Donaldson, P.; Thorne, H.; Goodwin, B.; et al. Assessing Gambling-Related Harm in Victoria: A public Health Perspective; Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation: Melbourne, Australian, 2016. Available online: https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/assessing-gambling-related-harm-in-victoria-a-public-health-perspective-69/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Dowling, N. The Impact of Gambling Problems on Families (AGRC Discussion Paper No. 1); Australian Gambling Research Centre: Melbourne, Australian, 2014; Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30673225.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Hing, N.; Breen, H.; Gordon, A.; Russell, A. Gambling harms and gambling help-seeking amongst Indigenous Australians. J. Gambl. Stud. 2014, 30, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langham, E.; Thorne, H.; Browne, M.; Donaldson, P.; Rose, J.; Rockloff, M. Understanding gambling related harm: A proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. A theory of regret regulation 1.0. J. Consum. Psych. 2007, 17, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hing, N.; Nuske, E.; Gainsbury, S.M.; Russell, A.M.T. Perceived stigma and self-stigma of problem gambling: Perspectives of people with gambling problems. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2015, 16, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, J.; Pols, R.; Lawn, S.; Battersby, M. The “Zone”: A Qualitative Exploratory Study of an Altered State of Awareness in Electronic Gaming Machine Problem Gambling. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, J.; Pols, R.; Lawn, S. The ‘merry-go-round’ of habitual relapse: A qualitative study of relapse in electronic gaming machine problem gambling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2019, 16, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| 20.66667 | 3.51188 | 2.02759 | 11.94266 | 29.39067 | 10.193 | 2 | 0.009 |

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | t | df | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Sig. (2-Tailed) | ||||||

| Problem Commence—Problem Completion | 6.33333 | 1.52753 | 0.88192 | 2.53875 | 10.12792 | 7.181 | 2 | 0.019 |

| Goal 1 Commence—Goal 1 Completion | 6.66667 | 2.30940 | 1.33333 | 0.92980 | 12.40354 | 5.000 | 2 | 0.038 |

| Goal 2 Commence—Goal 2 Completion | 7.66667 | 0.57735 | 0.33333 | 6.23245 | 9.10088 | 23.000 | 2 | 0.002 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oakes, J.; Northe, V.; Darwin, C.; Hopkins, L. Case Study Demonstration of the Potential Acceptability and Effectiveness of a Novel Telehealth Treatment for People Experiencing Gambling Harm. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316273

Oakes J, Northe V, Darwin C, Hopkins L. Case Study Demonstration of the Potential Acceptability and Effectiveness of a Novel Telehealth Treatment for People Experiencing Gambling Harm. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):16273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316273

Chicago/Turabian StyleOakes, Jane, Vicky Northe, Chris Darwin, and Liza Hopkins. 2022. "Case Study Demonstration of the Potential Acceptability and Effectiveness of a Novel Telehealth Treatment for People Experiencing Gambling Harm" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 23: 16273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316273

APA StyleOakes, J., Northe, V., Darwin, C., & Hopkins, L. (2022). Case Study Demonstration of the Potential Acceptability and Effectiveness of a Novel Telehealth Treatment for People Experiencing Gambling Harm. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16273. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316273